Carrot Or Stick: Protecting Historic Interiors Through

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Headquarters Troop, 51St Cavalry Brigade Armory: 321 Manor Road

Landmarks Preservation Commission August 10, 2010, Designation List 432 LP-2369 HEADQUARTERS TROOP, 51ST CAVALRY BRIGADE ARMORY, 321 Manor Road, Staten Island Built 1926-27; Werner & Windolph, architects; addition: New York State Office of General Services, 1969-70; Motor Vehicle Storage Building and Service Center built 1950, Alfred Hopkins & Associates, architects Landmark Site: Borough of Staten Island Block 332, Lot 4 in part, consisting of the portion of the lot west of a line beginning at the point on the southern curbline of Martling Avenue closest to the northeastern corner of the Motor Vehicle Storage Building and Service Center (“Bldg. No. 2” on a drawing labeled “Master Plan,” dated August 1, 1979, and prepared by the New York State Division of Military and Naval Affairs) and extending southerly to the northeastern corner of the Motor Vehicle Storage Building and Service Center, along the eastern line of said building to its southeastern corner, and to the point on the southern lot line closest to the southeastern corner of the Motor Vehicle Storage Building and Service Center. On August 11, 2009, the Landmarks Preservation Commission held a hearing on the proposed designation as a Landmark of the Headquarters Troop, 51st Cavalry Brigade Armory and the proposed designation of the related Landmark Site (Item No. 7). The hearing had been duly advertised in accordance with the provisions of law. Twelve people spoke in favor of designation, including Councilmember Kenneth Mitchell and representatives of the Four- Borough Neighborhood Preservation Alliance, Historic Districts Council, New York Landmarks Conservancy, North Shore Waterfront Conservancy of Staten Island, Preservation League of Staten Island, and West Brighton Restoration Society. -

Federal Register/Vol. 74, No. 142/Monday, July 27, 2009/Notices

37056 Federal Register / Vol. 74, No. 142 / Monday, July 27, 2009 / Notices and Douglas Sts., Forest Grove, 09000360, IOWA Orange County LISTED, 5/28/09 Madison County Murphy School, 3729 Murphy School Rd., Hillsborough, 09000637 PUERTO RICO Seerley, William and Mary (Messersmith) Caguas Municipality Barn and Milkhouse—Smokehouse, 1840 Transylvania County 137th La., Earlham, 09000621 Puente No. 6, SR 798, Km. 1.0, Rio Canas East Main Street Historic District, Ward, Caguas vicinity, 09000361, LISTED, MINNESOTA (Transylvania County MPS) 249–683 and 5/28/09 (Historic Bridges of Puerto Rico 768 East Main St.; 6–7 Rice St.; St. Phillip’s MPS) McLeod County Ln.; 1–60 Woodside Dr.; and 33 Deacon Komensky School, 19981 Major Ave., Ln., Brevard, 09000638 SOUTH CAROLINA Hutchinson, 09000622 UTAH Abbeville County Ramsey County Summit County Lindsay Cemetery, Lindsay Cemetery Rd., O’Donnell Shoe Company Building, 509 Due West vicinity, 09000364, LISTED, 5/ O’Mahony Dining Car No. 1107, 981 W. Sibley St., St. Paul, 09000623 27/09 Weber Canyon Rd., Oakley, 09000639 MISSISSIPPI VIRGINIA VIRGINIA Lee County Loudoun County Lunenburg County Carnation Milk Plant, 520 Carnation St., Round Hill Historic District, Area within the Fort Mitchell Depot, 5570–5605 Fort Mitchell Tupelo, 09000624 Round Hill town limits that is bounded Dr., Fort Mitchell, 09000640 roughly by VA 7 to the S., Locust St. to the Marion County Newport News Independent City W., Bridge on E, Round Hill, 09000366, Columbia North Residential Historic District, LISTED, 5/28/09 Simon Reid Curtis House, 10 Elmhurst St., Roughly bounded by High School and N. Newport News, 09000641 WASHINGTON Main St. -

Cheney Brothers, the New York Connection

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings Textile Society of America 1998 Cheney Brothers, the New York Connection Carol Dean Krute Wadsworth Atheneum Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf Part of the Art and Design Commons Dean Krute, Carol, "Cheney Brothers, the New York Connection" (1998). Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings. 183. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf/183 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Textile Society of America at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Cheney Brothers, the New York Connection Carol Dean Krute Wadsworth Atheneum The Cheney Brothers turned a failed venture in seri-culture into a multi-million dollar silk empire only to see it and the American textile industry decline into near oblivion one hundred years later. Because of time and space limitations this paper is limited to Cheney Brothers' activities in New York City which are, but a fraction, of a much larger story. Brothers and beginnings Like many other enterprising Americans in the 1830s, brothers Charles (1803-1874), Ward (1813-1876), Rush (1815-1882), and Frank (1817-1904), Cheney became engaged in the time consuming, difficul t business of raising silk worms until they discovered that speculation on the morus morticaulis, the white mulberry tree upon which the worms fed, might be far more profitable. As with all high profit operations the tree business was a high-risk venture, throwing many investors including the Cheney brothers, into bankruptcy. -

Common Errors in English by Paul Brians [email protected]

Common Errors in English by Paul Brians [email protected] http://www.wsu.edu/~brians/errors/ (Brownie points to anyone who catches inconsistencies between the main site and this version.) Note that italics are deliberately omitted on this page. What is an error in English? The concept of language errors is a fuzzy one. I'll leave to linguists the technical definitions. Here we're concerned only with deviations from the standard use of English as judged by sophisticated users such as professional writers, editors, teachers, and literate executives and personnel officers. The aim of this site is to help you avoid low grades, lost employment opportunities, lost business, and titters of amusement at the way you write or speak. But isn't one person's mistake another's standard usage? Often enough, but if your standard usage causes other people to consider you stupid or ignorant, you may want to consider changing it. You have the right to express yourself in any manner you please, but if you wish to communicate effectively you should use nonstandard English only when you intend to, rather than fall into it because you don't know any better. I'm learning English as a second language. Will this site help me improve my English? Very likely, though it's really aimed at the most common errors of native speakers. The errors others make in English differ according to the characteristics of their first languages. Speakers of other languages tend to make some specific errors that are uncommon among native speakers, so you may also want to consult sites dealing specifically with English as a second language (see http://www.cln.org/subjects/esl_cur.html and http://esl.about.com/education/adulted/esl/). -

Hotel Administration 1962-1963

CORNELL UNIVERSITY ANNOUNCEMENTS JULY 24, 1962 HOTEL ADMINISTRATION 1962-1963 SCHOOL OF HOTEL ADMINISTRATION ACADEMIC CALENDAR (Tentative) 1962-1963 1963-1964 Sept. 15. ...S ..................Freshman Orientation......................................................Sept. 21... .S Sept. 17...M ..................Registration, new students..............................................Sept. 23...M Sept. 18...T ..................Registration, old students................................................Sept. 24...T Sept. 19...W ..................Instruction begins, 1 p.m.................................................Sept. 25...W Nov. 7....W ..................Midterm grades due..........................................................Nov. 13...W Thanksgiving recess: Nov. 21.. .W ..................Instruction suspended, 12:50 p.m.................................. Nov. 27...W Nov. 26...M..................Instruction resumed, 8 a.m..............................................Dec. 2 ....M Dec. 19. .. .V V ..................Christmas recess..................................................................Dec. 21... .S Instruction suspended: 10 p.m. in 1962, 12:50 p.m. in 1963 Jan. 3.. .Th ..................Instruction resumed, 8 a.m............................................. Jan. 6... ,M Jan. 19 S..................First-term instruction ends............................................Jan. 25 S Jan. 21....M...................Second-term registration, old students......................Jan. 27....M Jan. 22. ...T ...................Examinations begin.........................................................Jan. -

CITYLAND NEW FILINGS & DECISIONS | December 2019

CITYLAND NEW FILINGS & DECISIONS | December 2019 CITY PLANNING PIPELINE New Applications Filed with DCP — December 1 to December 31, 2019 APPLICANT PROJECT/ADDRESS DESCRIPTION ULURP NO. REPRESENTATIVE ZONING TEXT AND MAP AMENDMENTS FWRA LLC Special Flushing Waterfront Application for a text amendment to establish a Special Flushing 200033 ZMQ; Ross F. Moskowitz, District Waterfront District, a waterfront certification, and a proposed 200034 ZRQ Stroock & Stroock & rezoning of portions of existing C4-2 and M3-1 districts to a MX Lavan LLP M1-2/R7A District. (CM Koo; District 20) Brisa Evergreen Beach 67th Street Rezoning This is a private application by Brisa Evergreen LLC and God’s 200230 ZMQ Ericka Keller LLC Battalion of Prayer Properties, Inc. requesting a zoning map amendment from an R4A to an R6 zoning district and a zoning text amendment to establish an MIH area within the project area to facilitate the development of 88 unit AIRS and a community facility (charter school) in Community District 14, Queens. Queens Realty 25-46 Far Rockaway Blvd This is a private application by Queens Realty Housing of NY Ltd 200323 ZMQ Richard Lobel Housing of NY Ltd Rezoning requesting a zoning maps amendment from an R4-1 to an R6 zoning district to facilitate multifamily development in Far Rockaway, Community District 14, Queens. Markland 4551, 4541 Furman Potential Rezoning to R7D/C2-4 and Text amendment to establish 200229 ZRX LLC MIH and Extend Transit Zone. SPECIAL PERMITS/OTHER ACTIONS Joseph Morace 101 Circle Road (2nd A ZR 11-43 for renewal of authorization is being sought by private 200211 CMR Renewal) applicant McGinn Real Estate Trust at 101 Circle Road in Todt Hill neighborhood, Community District #2, Staten Island. -

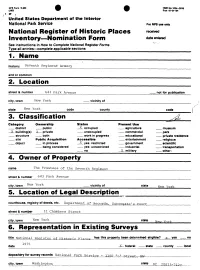

National Register of Historic Places Inventory Nomination Form Date

NFS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-OO18 Exp. 1O-31-84 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service For NFS UM only National Register of Historic Places Inventory Nomination Form date entered See instructions in How to Complete National Register Forms ^ Type all entries complete applicable sections 1. Name historic Seventh Regiment Armory and or common ______________________________ 2. Location street & number 643 Park Avenue __ not for publication city, town New York vicinity of state New York code county code 3. Classification ^x£ Category Ownership Status Present Use district public X occupied agriculture museum X building(s) X _ private unoccupied commercial park structure both work in progress educational private residence site Public Acquisition Accessible entertainment __ religious object in process X yes: restricted government scientific being considered .. yes: unrestricted industrial transportation no X military other: 4. Owner off Property name The Trustees of the Seventh Regiment street & number 64 3 Park Avenue city, town New York vicinity of state New York 5. Location off Legal Description _ courthouse, registry of deeds, etc. Department of Records, Surrogate ' s street & number 31 Chambers Street New York city, town ___________________________________ state York- 6. Representation in Existing Surveys title National Register of Historic has this property been determined eligible? no 1975 date X federal state county local depository for survey records National Park Service - 1100 "T." street, NW city, town___Washington -

Fall Hospitality Report Manhattan 2015

FALL HOSPITALITY REPORT (2015) MANHATTAN FALL HOSPITALITY REPORT MANHATTAN 2015 1 | P a g e FALL HOSPITALITY REPORT (2015) MANHATTAN EXECUTIVE SUMMARY According to the Starr report, Manhattan’s hotel sector has been growing by over 4.0 % since 2010 both by ADR and number of rooms. The demand still far exceeds supply especially for 5 star brands. Early in the hotel recovery in 2011, three star brands grew in number of rooms and ADR initially. As the recovery went into full swing by late 2013, four and five star hotel development continued to outpace three star hotel growth. Global investors are seeking five star hotel product in Manhattan and at $1.0 million up to $2.0 million per key. For instance, Chinese investors bought the Waldorf Astoria and the Baccarat Hotels both at substantially above $1.0 million per key. Manhattan is one of the best hotel markets in the world between growing tourism and inexpensive accommodations compared to other global gateway cities like London, Paris, Moscow, Hong Kong, etc. Any established global hotel brand also requires a presence in Manhattan. In 2014 alone, 4,348 keys were added to Manhattan’s existing 108,592 rooms. Currently, another 14,272 rooms are under construction in the city and about 4000 keys (1/3) are for boutique hotels. As of July 2015, the Manhattan market has approximately 118,000 keys. They are segmented as follows: Currently, there is a 4.0% annual compounded growth rate. Despite this growth, demand for hotel rooms from tourism, conventions, cultural events, and corporate use continues to grow as Manhattan is one of the most desirable locations for all of the above uses especially tourism from Asia and Europe. -

Allies Not Adversaries: Teaching Collaboration to the Next

Roger Williams University DOCS@RWU Feinstein Center for Pro Bono & Experiential Pro Bono Collaborative Staff ubP lications Learning 2008 Allies Not Adversaries: Teaching Collaboration to the Next Generation of Doctors and Lawyers to Address Social Inequality Elizabeth Tobin Tyler Roger Williams University School of Law Follow this and additional works at: http://docs.rwu.edu/law_feinstein_sp Part of the Bioethics and Medical Ethics Commons, Law Commons, and the Medical Education Commons Recommended Citation Tyler, Elizabeth Tobin, "Allies Not Adversaries: Teaching Collaboration to the Next Generation of Doctors and Lawyers to Address Social Inequality" (2008). Pro Bono Collaborative Staff Publications. Paper 1. http://docs.rwu.edu/law_feinstein_sp/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Feinstein Center for Pro Bono & Experiential Learning at DOCS@RWU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Pro Bono Collaborative Staff ubP lications by an authorized administrator of DOCS@RWU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TOBIN TYLER [FINAL 2].DOC 9/20/2008 3:24 PM ALLIES NOT ADVERSARIES: TEACHING COLLABORATION TO THE NEXT GENERATION OF DOCTORS AND LAWYERS TO ADDRESS SOCIAL INEQUALITY ELIZABETH TOBIN TYLER* INTRODUCTION ―Medicolegal education in law and medical schools can give students a chance to discover ‗that the other group did not come congenitally equipped with either horns or pointed tails.‘‖1 Stories of the antagonism between doctors and lawyers are deeply embedded in American culture. A 2005 New Yorker cartoon jokes, ―Hippocrates off the record: First, treat no lawyers.‖2 The distrust and hostility are not new. A commentator noted in 1971: The problem presented is an atmosphere of distrust, fear and antagonism—not all of which is unfounded. -

Media Contact: Jessica Busch Phone: (858) 217-3572 Email: [email protected]

Media Contact: Jessica Busch Phone: (858) 217-3572 Email: [email protected] FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE CUMMING CONTINUES FOCUS ON STRATEGIC NATIONWIDE EXPANSION WITH OPENING OF NEW YORK CITY OFFICE, BRINGS ON SEVERAL INDUSTRY VETERANS NEW YORK - (Oct. 15, 2013) – Cumming, an international project management and cost consulting firm, announced today it will further expand its East Coast presence with the opening of a New York office and the hiring of veteran talent. Supporting a nationwide growth plan, the construction management firm’s Midtown office located at 60 East 42nd Street will focus on serving the Greater New York City-area and growing its client base. “Expanding Cumming’s geographical footprint with a New York City office and adding leaders that have deep Tri-State experience, will allow us to better serve our clients as construction in the region continues to rebound,” said Peter Heald, President at Cumming. While the firm has been involved with numerous projects in the Greater New York City-area since 1998 - representing approximately $2 billion in development value - Cumming is solidifying its commitment to clients by adding a physical office and key senior talent. Regional project experience includes: EDITION New York, Waldorf Astoria New York, World Trade Center Towers 2 & 4, West 57th Street by Hilton Club, New York Public Library, Westchester County Medical Center, 432 Park Avenue, and SUNY College of Nanoscale Science and Engineering, among many others. Cumming’s New York-based team specializes in program, project and cost management. The team supports clients nationwide and across a broad range of building sectors. Noteworthy regional leaders that have recently joined the firm include: • John Perez, Vice President - Joining Cumming as Vice President, John has more than 26 years of construction and facilities management experience. -

Perspectives on the Opioid Crisis and the Workforce

Special Feature: Perspectives on the Opioid Crisis and the Workforce Reproduced with permission from Benefits Magazine, Volume 55, No. 7, July 2018, pages 28-33, published by the International Foundation of Employee Benefit Plans (www.ifebp.org), Brookfield, Wis. All rights reserved. Statements or opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views or positions of the International Foundation, its officers, directors or staff. No further transmission or electronic distribution of this MAGAZINE material is permitted. 28 benefits magazine july 2018 John S. Gaal, Ed.D., director of training and workforce development for the St. Louis– Kansas City Carpenters Regional Council, has spent the last two years researching the opioid crisis while he has seen its impact on the construction industry. Gaal offers his Perspectives on the Opioid own perspective on the matter and interviews four experts who recently participated in International Foundation panel discussions on opioids to get their views on how the opioid crisis started and efforts to treat and prevent the spread of opioid use disorder Crisis and the Workforce (OUD). John S. Gaal, Ed.D. John S. Gaal: As I’ve re- Hillbilly Elegy, refers to these phenom- Director of Training and searched the problem, ena as diseases of despair (Campbell, Workforce Development I’ve received input from 2017). St. Louis–Kansas City Carpenters a multitude of sources on Regional Council the opioids/heroin-relat- Mental Health, Chronic Pain St. Louis, Missouri ed crises. A recently re- and the Opioid Crisis [email protected] leased report from the state of Missouri Gaal: The opioids/heroin crisis has Joseph Ricciuti showed that nearly $13 billion per year negatively impacted people across all Co-Founder (approximately $35 million per day) spectrums within our communities. -

CITY PLANNING COMMISSION November 16, 2011 / Cale

CITY PLANNING COMMISSION ______________________________________________________________________________ November 16, 2011 / Calendar No. 12 N 120081 HKM ______________________________________________________________________________ IN THE MATTER OF a communication dated September 29, 2011, from the Executive Director of the Landmarks Preservation Commission regarding the landmark designation of the Madison Belmont Building, First Floor Interior, 181 Madison Avenue (Block 863, Lot 60), by the Landmarks Preservation Commission on September 20, 2011 (List No. 448/LP-2425), Borough of Manhattan, Community District 5. _________________________________________________________________________ Pursuant to Section 3020.8(b) of the New York City Charter, the City Planning Commission shall submit to the City Council a report with respect to the relation of any designation by the Landmarks Preservation Commission, whether a historic district or a landmark, to the Zoning Resolution, projected public improvements, and any plans for the development, growth, improvement or renewal of the area involved. On September 20, 2011 the Landmarks Preservation Commission (LPC) designated the first floor interior of the Madison Belmont Building at 181 Madison Avenue (Block 863, Lot 60) , as a city landmark. The landmark designation consists of the interior main lobby space, including the fixtures and components of this space, such as the wall, ceiling and floor surfaces, entrance and vestibule doors, grilles, bronze friezes and ornament, lighting fixtures, elevator doors, mailbox, interior doors, clock, fire command box, radiators, and elevator sign. The first floor interior lobby of the Madison Belmont Building, located between East 33rd and East 34th streets in Manhattan Community District 5, is a rare, intact and ornate Eclectic Revival style space designed as part of the original construction of the building 1924-1925.