Revisiting Popular Histories of the Syrian Christians in the Early Modern Period

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Catholic Church and Divinization Through Education

Research Paper ISSN-2455-0736 (Print) Peer Reviewed Journal ISSN-2456-4052 (Online) The Catholic Church And Divinization Through Education Bijumon George Kochupurackal and Dr. Reena George Research & Development Centre, Bharathiar University, Coimbatore, Tamilnadu Associate Professor, Karmela Rani Training College, Kollam, Kerala [email protected] Abstract The Catholic Church is considered as the largest educational institution in the world. For the church education is ‘a divine mission’ for transforming the world based on the Gospel values of ‘service in love, peace rooted in justice and fellowship based on equality’. Everyone irrespective of caste, creed and gender have access to education with the intervention of the church in the educational field. Until then in Kerala and in the other states of India education was reserved to high class people. Certain political leaders and media persons rigorously and continuously criticize the church and try to condemn all the services and contributions of the church in the field education. The church proposes that education should be based on moral, individual and social values. Thus the proper and ultimate aim of education is divinization of human person. The role of the church in education is not just to make a human better human, not just to make him a more social being with good social and moral or ethical values but make him to actualize the divine potential in him. Introduction The Catholic Church is always interested in providing education. She is active both in the fields of religious and secular education. The Catholic Church is the biggest educational institution in the world. When we speak about the global educational perspective we can never side back the role of the Catholic Church in providing worldwide education. -

The Church Missionary Society and the Christians of Kerala, 1813-1840

Half-Brothers in Christ: The Church Missionary Society and the Christians of Kerala, 1813-1840 by Joseph Gerald Howard M. A. (History), University at Buffalo, State University of New York, 2010 Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the Department of History Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences Joseph Gerald Howard 2014 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Fall 2014 Approval Name: Joseph Gerald Howard Degree: Master of Arts (History) Title: Half-Brothers in Christ: The Church Missionary Society and the Christians of Kerala, 1813-1840 Examining Committee: Chair: Aaron Windel Assistant Professor of History Paul Sedra Senior Supervisor Associate Professor of History Derryl MacLean Supervisor Associate Professor of History Mary-Ellen Kelm Supervisor Professor of History Laura Ishiguro External Examiner Assistant Professor Department of History University of British Columbia Date Defended: August 28, 2014 ii Partial Copyright Licence iii Abstract In the 1810s, the Church Missionary Society (CMS) established the College at Cottayam in south India to educate boys intended for the priesthood in the local, indigenous church. While their goal was to help the church, their activities increased British power in the community. The results of CMS involvement included increasing interference of British officials in matters internal to the Malankara Church (e.g., episcopal succession), tacit recognition of the authority of colonial courts to resolve disputes in the church, and the fragmentation of the St. Thomas Christian community. These effects reshaped the church into something more consistent with British Christianity and more subject to British rule. Keywords: British Empire; Christianity; India; mission iv Dedication In memory of M. -

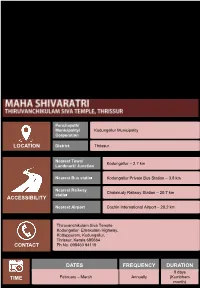

LOCATION District Thrissurthrissur

Panchayath/ Municipality/ KodungallurKodungallur Municipality Municipality Corporation LOCATION District ThrissurThrissur Nearest Town/ KodungallurKodungallur – – 2.7 2.7 km km Landmark/ Junction Nearest Bus statio KodungallurKodungallur Private Private Bus Bus Station Station – – 3.8 3.8 km km Nearest Railway ChalakudyChalakudy Railway Railway Station Station – – 20.7 20.7 km km statio ACCESSIBILITY Nearest Airport CochinCochin International International Airport Airport – – 28.2 28.2 km km ThiruvanchikulamThiruvanchikulam Siva Siva Temple Temple KodungallurKodungallur-- Ernakulam Ernakulam Highway, Highway, KottappuramKottappuram, ,Kodungallur Kodungallur, , ThrissurThrissur, ,Kerala Kerala 680664 680664 CONTACT PhPh No: No: 098460 098460 94119 94119 DATES FREQUENCY DURATION 8 days TIME FebruaryFebruary – – March March Annually (Kumbham month) ABOUT THE FESTIVAL (Legend/History/Myth) The temple is believed to be built by Cheraman Perumal, a legendary Chera king. It is believed that Cheraman Perumal and his minister and friend Sundaramoorthy Nayanar left their life in the temple. This temple had undergone several invasions in the flow of time. The Dutch and The Tipu Sulthan of Mysore are the prominent ones, who demolished this temple during their invasions. The temple was renovated in 1801 AD. It is believed that the main idol of worship, Siva linga is brought from Chidambaram Rameshwara temple. It was one of the most popular Siva temples in South India. Thiruvanchikulam Shiva Temple suffered war damages in 1670 and in late 18th century. In the late mediaeval Thiruvanchikulam was under the ruler of Cochin but occasionally, the Zamorin of Calicut had usurped the control. The saint Sundarmoorthy Nayanar and Cheraman Perumal (both were close- friends) worshipped Lord Shiva leading to eternal bliss. They reached Kailas by riding on a 1000- tusked white elephant by Nayanar and on a blue horse by Perumal. -

KERALA SOLID WASTE MANAGEMENT PROJECT (KSWMP) with Financial Assistance from the World Bank

KERALA SOLID WASTE MANAGEMENT Public Disclosure Authorized PROJECT (KSWMP) INTRODUCTION AND STRATEGIC ENVIROMENTAL ASSESSMENT OF WASTE Public Disclosure Authorized MANAGEMENT SECTOR IN KERALA VOLUME I JUNE 2020 Public Disclosure Authorized Prepared by SUCHITWA MISSION Public Disclosure Authorized GOVERNMENT OF KERALA Contents 1 This is the STRATEGIC ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT OF WASTE MANAGEMENT SECTOR IN KERALA AND ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL MANAGEMENT FRAMEWORK for the KERALA SOLID WASTE MANAGEMENT PROJECT (KSWMP) with financial assistance from the World Bank. This is hereby disclosed for comments/suggestions of the public/stakeholders. Send your comments/suggestions to SUCHITWA MISSION, Swaraj Bhavan, Base Floor (-1), Nanthancodu, Kowdiar, Thiruvananthapuram-695003, Kerala, India or email: [email protected] Contents 2 Table of Contents CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION TO THE PROJECT .................................................. 1 1.1 Program Description ................................................................................. 1 1.1.1 Proposed Project Components ..................................................................... 1 1.1.2 Environmental Characteristics of the Project Location............................... 2 1.2 Need for an Environmental Management Framework ........................... 3 1.3 Overview of the Environmental Assessment and Framework ............. 3 1.3.1 Purpose of the SEA and ESMF ...................................................................... 3 1.3.2 The ESMF process ........................................................................................ -

Christians and Jews in Muslim Societies

Arabic and its Alternatives Christians and Jews in Muslim Societies Editorial Board Phillip Ackerman-Lieberman (Vanderbilt University, Nashville, USA) Bernard Heyberger (EHESS, Paris, France) VOLUME 5 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/cjms Arabic and its Alternatives Religious Minorities and Their Languages in the Emerging Nation States of the Middle East (1920–1950) Edited by Heleen Murre-van den Berg Karène Sanchez Summerer Tijmen C. Baarda LEIDEN | BOSTON Cover illustration: Assyrian School of Mosul, 1920s–1930s; courtesy Dr. Robin Beth Shamuel, Iraq. This is an open access title distributed under the terms of the CC BY-NC 4.0 license, which permits any non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided no alterations are made and the original author(s) and source are credited. Further information and the complete license text can be found at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ The terms of the CC license apply only to the original material. The use of material from other sources (indicated by a reference) such as diagrams, illustrations, photos and text samples may require further permission from the respective copyright holder. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Murre-van den Berg, H. L. (Hendrika Lena), 1964– illustrator. | Sanchez-Summerer, Karene, editor. | Baarda, Tijmen C., editor. Title: Arabic and its alternatives : religious minorities and their languages in the emerging nation states of the Middle East (1920–1950) / edited by Heleen Murre-van den Berg, Karène Sanchez, Tijmen C. Baarda. Description: Leiden ; Boston : Brill, 2020. | Series: Christians and Jews in Muslim societies, 2212–5523 ; vol. -

Book Review:" Christianity in India: from Beginnings to the Present"

Journal of Hindu-Christian Studies Volume 22 Article 21 January 2009 Book Review: "Christianity in India: From Beginnings to the Present" Kristin Bloomer Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.butler.edu/jhcs Part of the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Bloomer, Kristin (2009) "Book Review: "Christianity in India: From Beginnings to the Present"," Journal of Hindu-Christian Studies: Vol. 22, Article 21. Available at: https://doi.org/10.7825/2164-6279.1448 The Journal of Hindu-Christian Studies is a publication of the Society for Hindu-Christian Studies. The digital version is made available by Digital Commons @ Butler University. For questions about the Journal or the Society, please contact [email protected]. For more information about Digital Commons @ Butler University, please contact [email protected]. Bloomer: Book Review: "Christianity in India: From Beginnings to the Present" Book Reviews 63 Christianity in India: From Beginnings to the Present. Robert Eric Frykenberg, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2P08, 564 pp. UNTIL now, no one book in English has informative for the beginner, they seem to want attempted to cover the vast topic of Christianity to belong to another book. The effect of these in India.! Robert Frykenberg's recent work does early, seventy pages on the narrative frame, so in a manner that is not only timely and useful however, is strong: Christianity did not enter for scholars of Indian history and religion; it is India in a vacuum, nor did it steamroll in, also ambitious, to which its heft and length leveling everything in its path. it entered a attest. The author, a prof~ssor emeritus of specific geography, politics and culture through' history at Northwestern University, has spent the individual Christians who interacted with other past fifty years of his life studying Christianity individual Christians and non-Christians from a in India. -

Living to Tell the Tale-The Knanaya Christians of Kerala

Living to Tell The Tale-The Knanaya Christians of Kerala Maria Ann Mathew , Department of Sociology, Delhi School of Economics. LIVING TO TELL THE TALE- THE KNANAYA CHRISTIANS OF KERALA In the first week of August, Kottayam town witnessed a protest rally by approximately 600 former members of the Knanaya Christians. The rally vouched for the restoration of the erstwhile Knanaya identity of the participants, who by way of marrying outside the Knanaya circle, got ex- communicated from the community. What is it about the Knanaya Community that people who have been ousted from it, refuse to part with their Knanaya identity? Who can give them their Knanaya Identity back? What is the nature of this identity? Belonging to a Jewish-Christian Ancestry, the Knanaya Christians of Kerala are believed to have reached the port of Kodungaloor (Kerala), in 345 CE, under the leadership of Thomas of Cana. This group, also known as ‘Thekkumbaggar’ (Southists) claims to have been practising strict endogamy since the time of their arrival. ‘Thekkumbaggar’ has been opposed to the ‘Vadakkumbaggar’ (Northists) who were the native Christians of that time, for whose ecclestiacal and spiritual uplift, it is believed that the Knanayas migrated from South Mesopotamia. However, the Southists did not involve in marriage relations with the Northists. The Knanaya Christians today, number up to around 2,50,000 people. Within the Knanaya Christians, there are two groups that follow different churches-one follows the Catholic rite and the other , the Jacobite rite. This division dates back to the Coonen Kurush Satyam of 1653, when the Syrian Christians of Kerala, revolted against the Portuguese efforts to bring the Syrian Christians under the Catholic rite. -

Kerala Floods - 2018

Prot No. 2558/2018/S/ABP : 30-8-2018 KERALA FLOODS - 2018 A REPORT BY ARCHBISHOP ANDREWS THAZHATH Trichur August 30, 2018 1 HEAVY FLOODS AND NATURAL CATASTROPHE IN KERALA JULY-AUGUST 2018 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. BRIEF HISTORY .............................................................................................................. 3 1. Heavy Rainfall in Kerala: .................................................................................................... 3 2. Floods and Landslides : ....................................................................................................... 4 3. Most Affected Districts/ Regions : ...................................................................................... 6 4. Death toll:............................................................................................................................. 6 5. Catastrophe due to flash flooding : ...................................................................................... 6 II. RELIEF ACTION BY KERALA GOVERNMENT ...................................................... 7 7. Latest Government Data : .................................................................................................... 8 8. Data of Damages prepared by KSSF . ................................................................................ 8 III. KERALA CATHOLIC CHURCH IN RELIEF ACTION............................................. 9 9. Involvement of the Catholic Church : ................................................................................. -

Payment Locations - Muthoot

Payment Locations - Muthoot District Region Br.Code Branch Name Branch Address Branch Town Name Postel Code Branch Contact Number Royale Arcade Building, Kochalummoodu, ALLEPPEY KOZHENCHERY 4365 Kochalummoodu Mavelikkara 690570 +91-479-2358277 Kallimel P.O, Mavelikkara, Alappuzha District S. Devi building, kizhakkenada, puliyoor p.o, ALLEPPEY THIRUVALLA 4180 PULIYOOR chenganur, alappuzha dist, pin – 689510, CHENGANUR 689510 0479-2464433 kerala Kizhakkethalekal Building, Opp.Malankkara CHENGANNUR - ALLEPPEY THIRUVALLA 3777 Catholic Church, Mc Road,Chengannur, CHENGANNUR - HOSPITAL ROAD 689121 0479-2457077 HOSPITAL ROAD Alleppey Dist, Pin Code - 689121 Muthoot Finance Ltd, Akeril Puthenparambil ALLEPPEY THIRUVALLA 2672 MELPADAM MELPADAM 689627 479-2318545 Building ;Melpadam;Pincode- 689627 Kochumadam Building,Near Ksrtc Bus Stand, ALLEPPEY THIRUVALLA 2219 MAVELIKARA KSRTC MAVELIKARA KSRTC 689101 0469-2342656 Mavelikara-6890101 Thattarethu Buldg,Karakkad P.O,Chengannur, ALLEPPEY THIRUVALLA 1837 KARAKKAD KARAKKAD 689504 0479-2422687 Pin-689504 Kalluvilayil Bulg, Ennakkad P.O Alleppy,Pin- ALLEPPEY THIRUVALLA 1481 ENNAKKAD ENNAKKAD 689624 0479-2466886 689624 Himagiri Complex,Kallumala,Thekke Junction, ALLEPPEY THIRUVALLA 1228 KALLUMALA KALLUMALA 690101 0479-2344449 Mavelikkara-690101 CHERUKOLE Anugraha Complex, Near Subhananda ALLEPPEY THIRUVALLA 846 CHERUKOLE MAVELIKARA 690104 04793295897 MAVELIKARA Ashramam, Cherukole,Mavelikara, 690104 Oondamparampil O V Chacko Memorial ALLEPPEY THIRUVALLA 668 THIRUVANVANDOOR THIRUVANVANDOOR 689109 0479-2429349 -

The Grace of God and the Travails of Contemporary Indian Catholicism Kerry P

Journal of Global Catholicism Volume 1 Issue 1 Indian Catholicism: Interventions & Article 3 Imaginings September 2016 The Grace of God and the Travails of Contemporary Indian Catholicism Kerry P. C. San Chirico Villanova University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://crossworks.holycross.edu/jgc Part of the Asian History Commons, Asian Studies Commons, Catholic Studies Commons, Christian Denominations and Sects Commons, Christianity Commons, Comparative Methodologies and Theories Commons, Comparative Philosophy Commons, Cultural History Commons, Digital Humanities Commons, Hindu Studies Commons, History of Christianity Commons, History of Religion Commons, History of Religions of Eastern Origins Commons, History of Religions of Western Origin Commons, Inequality and Stratification Commons, Intellectual History Commons, Liturgy and Worship Commons, Missions and World Christianity Commons, Oral History Commons, Other Anthropology Commons, Place and Environment Commons, Politics and Social Change Commons, Practical Theology Commons, Quantitative, Qualitative, Comparative, and Historical Methodologies Commons, Race and Ethnicity Commons, Race, Ethnicity and Post-Colonial Studies Commons, Regional Sociology Commons, Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons, Rural Sociology Commons, Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons, Social History Commons, Sociology of Culture Commons, Sociology of Religion Commons, and the South and Southeast Asian Languages and Societies Commons Recommended Citation San Chirico, Kerry P. C. (2016) "The Grace of God and the Travails of Contemporary Indian Catholicism," Journal of Global Catholicism: Vol. 1: Iss. 1, Article 3. p.56-84. DOI: 10.32436/2475-6423.1001 Available at: https://crossworks.holycross.edu/jgc/vol1/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by CrossWorks. -

The Highlands Grapevine

During the month of May we were asked to pray for the nations of Asia and the theme of our prayers was that “God would send out workers to gather in His harvest”. I found this lovely poem written by a man who had a dream. It is based on the story in Matt. 21:18-20 when Jesus looked for fruit on the fig tree and found nothing but leaves. The time of the harvest was ended, And the summer of life was gone, When in from the fields came the reapers, Called home by the dip of the sun; I saw them each bearing a burden Of toilsomely ingathered sheaves; They brought them in love to the Master, But I could bring nothing but leaves. The years that He gave I had wasted, Nor thought I how soon they would fly, While others toiled for the harvest, I carelessly let them slip by; I idled about without purpose, Nor cared I, but now how it grieves; While others brought fruit to their Master, I found I had nothing but leaves. Then soon from my dream I was wakened, And sad was my heart, for I knew That though my life’s day was not over, Ere long I should bid it adieu. I started in shame and in sorrow, I turned from the sin that deceives; Henceforth I must toil for the Saviour Or maybe bring nothing but leaves. (by Jack Selfridge) On the Sunday after Easter, Pete told us all about ‘Doubting Thomas’. I found myself wondering what happened to Thomas. -

International Seminar on St Thomas Christians Through the Ages: a Historiographical Approach 30, 31 January, 1 February 2018

International Seminar on St Thomas Christians through the Ages: A Historiographical Approach 30, 31 January, 1 February 2018 The origin, development and the vicissitudes of the St Thomas Christians in India under native and European powers who established their sway over the subcontinent of India for a couple of centuries have been attracting the attention of scholars from far and wide. Both the Indian and European scholars tried to delve deeper into the origin of Christianity in India and a number of them proved the apostolic origin though, of course, there are a few “doubting –Thomases” among them. The current generation and their progeny will assuredly benefit a lot if the works on the various aspects of the St Thomas Christians are critically assessed and brought to their notice before they disappear from print media. It is commonplace understanding that history is re-constructed with the aid of different sources like archaeological, numismatic, and epigraphic evidences, near contemporary literary works, ballads or ancient popular songs, patristic testimonies and living tradition. Basic Christian communities in various parts of the coastal Malabar since the first Century A.D speak for the evangelization of the Apostle at the beginning of the Christian era. The knowledge about the existence of Christian settlements in Kerala dating their origin back to St Thomas, the Apostle prompted St Thomas Christians living in the Persian Empire, following Eastern liturgical and theological practices, to come and strengthen their fellow-Christians in India in the fourth and the ninth centuries. The copper plates granted to the leaders of the migrating groups stand strong testimony to the nature of these groups.