Quercus Prinus L. and Quercus Alba L. F

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Oaks (Quercus Spp.): a Brief History

Publication WSFNR-20-25A April 2020 Oaks (Quercus spp.): A Brief History Dr. Kim D. Coder, Professor of Tree Biology & Health Care / University Hill Fellow University of Georgia Warnell School of Forestry & Natural Resources Quercus (oak) is the largest tree genus in temperate and sub-tropical areas of the Northern Hemisphere with an extensive distribution. (Denk et.al. 2010) Oaks are the most dominant trees of North America both in species number and biomass. (Hipp et.al. 2018) The three North America oak groups (white, red / black, and golden-cup) represent roughly 60% (~255) of the ~435 species within the Quercus genus worldwide. (Hipp et.al. 2018; McVay et.al. 2017a) Oak group development over time helped determine current species, and can suggest relationships which foster hybridization. The red / black and white oaks developed during a warm phase in global climate at high latitudes in what today is the boreal forest zone. From this northern location, both oak groups spread together southward across the continent splitting into a large eastern United States pathway, and much smaller western and far western paths. Both species groups spread into the eastern United States, then southward, and continued into Mexico and Central America as far as Columbia. (Hipp et.al. 2018) Today, Mexico is considered the world center of oak diversity. (Hipp et.al. 2018) Figure 1 shows genus, sub-genus and sections of Quercus (oak). History of Oak Species Groups Oaks developed under much different climates and environments than today. By examining how oaks developed and diversified into small, closely related groups, the native set of Georgia oak species can be better appreciated and understood in how they are related, share gene sets, or hybridize. -

Native Nebraska Woody Plants

THE NEBRASKA STATEWIDE ARBORETUM PRESENTS NATIVE NEBRASKA WOODY PLANTS Trees (Genus/Species – Common Name) 62. Atriplex canescens - four-wing saltbrush 1. Acer glabrum - Rocky Mountain maple 63. Atriplex nuttallii - moundscale 2. Acer negundo - boxelder maple 64. Ceanothus americanus - New Jersey tea 3. Acer saccharinum - silver maple 65. Ceanothus herbaceous - inland ceanothus 4. Aesculus glabra - Ohio buckeye 66. Cephalanthus occidentalis - buttonbush 5. Asimina triloba - pawpaw 67. Cercocarpus montanus - mountain mahogany 6. Betula occidentalis - water birch 68. Chrysothamnus nauseosus - rabbitbrush 7. Betula papyrifera - paper birch 69. Chrysothamnus parryi - parry rabbitbrush 8. Carya cordiformis - bitternut hickory 70. Cornus amomum - silky (pale) dogwood 9. Carya ovata - shagbark hickory 71. Cornus drummondii - roughleaf dogwood 10. Celtis occidentalis - hackberry 72. Cornus racemosa - gray dogwood 11. Cercis canadensis - eastern redbud 73. Cornus sericea - red-stem (redosier) dogwood 12. Crataegus mollis - downy hawthorn 74. Corylus americana - American hazelnut 13. Crataegus succulenta - succulent hawthorn 75. Euonymus atropurpureus - eastern wahoo 14. Fraxinus americana - white ash 76. Juniperus communis - common juniper 15. Fraxinus pennsylvanica - green ash 77. Juniperus horizontalis - creeping juniper 16. Gleditsia triacanthos - honeylocust 78. Mahonia repens - creeping mahonia 17. Gymnocladus dioicus - Kentucky coffeetree 79. Physocarpus opulifolius - ninebark 18. Juglans nigra - black walnut 80. Prunus besseyi - western sandcherry 19. Juniperus scopulorum - Rocky Mountain juniper 81. Rhamnus lanceolata - lanceleaf buckthorn 20. Juniperus virginiana - eastern redcedar 82. Rhus aromatica - fragrant sumac 21. Malus ioensis - wild crabapple 83. Rhus copallina - flameleaf (shining) sumac 22. Morus rubra - red mulberry 84. Rhus glabra - smooth sumac 23. Ostrya virginiana - hophornbeam (ironwood) 85. Rhus trilobata - skunkbush sumac 24. Pinus flexilis - limber pine 86. Ribes americanum - wild black currant 25. -

Plant Blindness Identification

Plant Blindness Identification 1 broadleaf plantain Plantago major; introduced weed, but not harmful to local ecology; originally from Europe, now one of the most widely distributed plant species in the world; one of the first plants from Europe to establish populations in North America. Also known as white man’s footprint, for it seemed to follow European colonists everywhere they went. 1 white clover Trifolium repens; introduced weed, but not harmful to local ecology; much loved by honeybees 2 dandelion Taraxicum officinale; introduced weed, but not harmful to local ecology; distributed across the world, the leaves are edible 3 pokeweed Phytolacca americana; weedy native, very valuable plant for birds, who eat the berries; this plant is highly toxic to humans, both leaves and berries 4 daylily Hemerocallis (this one happens to be ‘Stella d’Oro’); introduced, not invasive; native to east Asia, daylilies have been cultivated for hundreds of years, with more than 80,000 different varieties 5 fern Some introduced ferns can be harmful invasives for local ecology; most ferns prefer shady areas with moist soil, although many will tolerate sun and some will grow in extremely dry conditions 6 mophead hydrangea Hydrangea macrophylla; introduced, not invasive; native to Japan, this is one of the most commonly used garden plants in the southeast; the flowers can be either pink or blue, depending on the acidity of the soil 7 nandina Nandina domestica; introduced, harmful invasive for local ecology; the berries are very toxic to birds; native to -

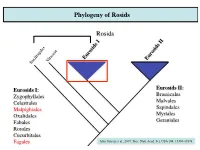

Phylogeny of Rosids! ! Rosids! !

Phylogeny of Rosids! Rosids! ! ! ! ! Eurosids I Eurosids II Vitaceae Saxifragales Eurosids I:! Eurosids II:! Zygophyllales! Brassicales! Celastrales! Malvales! Malpighiales! Sapindales! Oxalidales! Myrtales! Fabales! Geraniales! Rosales! Cucurbitales! Fagales! After Jansen et al., 2007, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 104: 19369-19374! Phylogeny of Rosids! Rosids! ! ! ! ! Eurosids I Eurosids II Vitaceae Saxifragales Eurosids I:! Eurosids II:! Zygophyllales! Brassicales! Celastrales! Malvales! Malpighiales! Sapindales! Oxalidales! Myrtales! Fabales! Geraniales! Rosales! Cucurbitales! Fagales! After Jansen et al., 2007, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 104: 19369-19374! Alnus - alders A. rubra A. rhombifolia A. incana ssp. tenuifolia Alnus - alders Nitrogen fixation - symbiotic with the nitrogen fixing bacteria Frankia Alnus rubra - red alder Alnus rhombifolia - white alder Alnus incana ssp. tenuifolia - thinleaf alder Corylus cornuta - beaked hazel Carpinus caroliniana - American hornbeam Ostrya virginiana - eastern hophornbeam Phylogeny of Rosids! Rosids! ! ! ! ! Eurosids I Eurosids II Vitaceae Saxifragales Eurosids I:! Eurosids II:! Zygophyllales! Brassicales! Celastrales! Malvales! Malpighiales! Sapindales! Oxalidales! Myrtales! Fabales! Geraniales! Rosales! Cucurbitales! Fagales! After Jansen et al., 2007, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 104: 19369-19374! Fagaceae (Beech or Oak family) ! Fagaceae - 9 genera/900 species.! Trees or shrubs, mostly northern hemisphere, temperate region ! Leaves simple, alternate; often lobed, entire or serrate, deciduous -

A Comparative Analysis of Quercus

A Study of the Age Class Structure of Quercus alba, Quercus coccinea and Quercus velutina: A Comparative Analysis of Quercus Species Reproduction as an Indicator of Forest Succession within the Long Island Pine Barrens Core Area KATHRYN GUTLEBER (Connecticut College, New London, CT 06320) TIMOTHY GREEEN, Ph.D. (Brookhaven National Lab, Upton, NY 11973-5000) Investigation of the age class structure of Quercus species within the Long Island Pine Barrens Core Area is an important aspect of monitoring the health of the Pine Barrens. The reproduction of Quercus alba, Quercus coccinea and Quercus velutina is a primary indicator of the possibility of the successional change from a pine to an oak dominated forest. The rates of reproduction for Quercus alba, Quercus coccinea and Quercus velutina can also be used to foresee the possible dominance of one particular Quercus species in forest succession. By comparing the numbers of seedlings, saplings and mature trees, the success of reproduction for these three different Quercus species was analyzed. The numbers of seedlings and saplings were recorded through the use of four two-meter wide belt transects within sixteen by twenty-five meter plots. These plots were located within the Pine Barrens subtargets of Pitch Pine, Pine-Oak, Oak-Pine and Coastal Oak forests. The number of mature trees was recorded within these same plots. This study found the success of reproduction of Quercus alba, Quercus coccinea and Quercus velutina within Pitch Pine, Pine-Oak, Oak-Pine and Coastal Oak forests to be relatively low. Within the four different forest communities surveyed, Quercus alba, Quercus coccinea and Quercus velutina all displayed a low number of saplings, indicating that current reproduction of these Quercus species is not very successful. -

The Distribution of the Genus Quercus in Illinois: an Update

Transactions of the Illinois State Academy of Science received 3/19/02 (2002), Volume 95, #4, pp. 261-284 accepted 6/23/02 The Distribution of the Genus Quercus in Illinois: An Update Nick A. Stoynoff Glenbard East High School Lombard, IL 60148 William J. Hess The Morton Arboretum Lisle, IL 60532 ABSTRACT This paper updates the distribution of members of the black oak [section Lobatae] and white oak [section Quercus] groups native to Illinois. In addition a brief discussion of Illinois’ spontaneously occurring hybrid oaks is presented. The findings reported are based on personal collections, herbarium specimens, and published documents. INTRODUCTION The genus Quercus is well known in Illinois. Although some taxa are widespread, a few have a limited distribution. Three species are of “special concern” and are listed as either threatened (Quercus phellos L., willow oak; Quercus montana Willd., rock chestnut oak) or endangered (Quercus texana Buckl., Nuttall’s oak) [Illinois Endangered Species Pro- tection Board 1999]. The Illinois Natural History Survey has dedicated a portion of its website [www.INHS.uiuc.edu] to the species of Quercus in Illinois. A discussion of all oaks from North America is available online from the Flora of North America Associa- tion [http://hua.huh.harvard.edu/FNA/] and in print [Jensen 1997, Nixon 1997, Nixon and Muller 1997]. The National Plant Data Center maintains an extensive online database [http://plants.usda.gov] documenting information on plants in the United States and its territories. Extensive oak data are available there [U.S.D.A. 2001]. During the last 40 years the number of native oak species recognized for Illinois by vari- ous floristic authors has varied little [Tables 1 & 2]. -

Common Oaks of the Chicago Region 1 the Field Museum – Division of Environment, Culture, and Conservation

Quercus of the Chicago Region, USA Common Oaks of the Chicago Region 1 The Field Museum – Division of Environment, Culture, and Conservation Produced by: Kathryn Stiver Corio and Rebecca Schillo, The Field Museum [http://fieldmuseum.org/explore/department/ecco] Images © Kathryn Corio, Ms, Botanist, Cofrin Center for Biodiversity, Green Bay, WI and John Balaban, The Field Museum © Environment, Culture, and Conservation, The Field Museum, Chicago, IL 60605 USA [http://www.fmnh.org/IDtools] [[email protected]] version 1 10/2012 GROUP 1: Unlobed to shallowly- lobed leaves 1 Quercus bicolor Key Characters: 1) Upper leaf surface dark green; underside whitish and covered in short soft hairs 2) Acorn borne on long fuzzy Swamp White Oak stalks 3) Frequent in moist woodlands and floodplains 4) Distinguished from white and bur oaks by its shallow leaf lobes. 2 Quercus imbricaria Key Characters: 1) Oblong leaves with smooth edges 2) Acorn nearly globular 3) Locally common in dry woodlands. Shingle Oak 3 Quercus muhlenbergii Key Characters: 1) Leaves long, slender, coarsely toothed 2) 9 to 13 teeth on each side 3) Occasionally found on rocky, wooded Chinquapin Oak slopes. GROUP 2: Lobed leaves with pointed bristle tips 4 Quercus velutina Key Characters: 1) Upperside of the leaf shiny, underside scurfy and hairy 2) Inner bark yellow-orange, very bitter 3) Common Black Oak in dry, sandy, upland terrain. Quercus of the Chicago Region, USA Common Oaks of the Chicago Region 2 The Field Museum – Division of Environment, Culture, and Conservation Produced by: Kathryn Stiver Corio and Rebecca Schillo, The Field Museum [http://fieldmuseum.org/explore/department/ecco] Images © Kathryn Corio, Ms, Botanist, Cofrin Center for Biodiversity, Green Bay, WI and John Balaban, The Field Museum © Environment, Culture, and Conservation, The Field Museum, Chicago, IL 60605 USA [http://www.fmnh.org/IDtools] [[email protected]] version 1 10/2012 GROUP 2 cont. -

Trees, Shrubs & Vines Partial Species List Shrubs Vines Vines

National Park Service Shrubs Vines U.S. Department of the Interior Congaree National Park Black alder, winterberry (Ilex verticillata) Coral greenbrier (Smilax walteri) Buttonbush (Cephalanthus occidentalis) Cross vine (Bignonia capreolata) Chickasaw plum (Prunus angustifolia) Eastern poison ivy Dwarf palmetto (Sabal minor) (Toxicodendron radicans ssp. radicans) Trees, Shrubs & Vines Georgia hackberry (Celtis tenuifolia) Japanese honeysuckle (Lonicera japonica) * Partial Species List Mountain laurel (Kalmia latifolia) Kudzu (Pueraria lobata) * Poison sumac (Toxicodendron vernix) Laurel greenbrier (Smilax laurifolia) Red buckeye (Aesculus pavia) Muscadine (Vitis rotundifolia) Redbay (Persea borbonia) Poison sumac (Toxicodendron vernix) Smooth sumac (Rhus glabra) Rattanvine, Alabama supplejack Sourwood (Oxydendrum arboreum) (Berchemia scandens) Sweetbay, Swamp magnolia (Magnolia virginiana) Saw greenbrier (Smilax bona-nox) Sweetleaf, Horse-sugar (Symplocos tinctoria) Summer grape (Vitis aestivalis) Winged sumac (Rhus copallinum var. latifolia) Sweet grape (Vitis cinerea) Yaupon (Ilex vomitoria) Sweet peppervine (Ampelopsis arborea) Trumpet creeper (Campsis radicans) Trumpet honeysuckle (Lonicera sempervirens) Virginia creeper (Parthenocissus quinquefolia) Wisteria (Wisteria frutescens) Yellow jessamine (Gelsemium sempervirens) Carolina jessamine (Gelsemium sempervirens) Vines Alabama supplejack (Berchemia scandens) Bristly greenbriar (Smilax tamnoides) Carolina moonseed (Cocculus carolinus) Cat greenbriar (Smilax glauca) Climbing hydrangea -

Street Trees for Iowa Communities This Document Offers Tree Selection Suggestions (Species and Cultivars) for Use Along Neighborhood and Municipal Streets

Street Trees for Iowa Communities This document offers tree selection suggestions (species and cultivars) for use along neighborhood and municipal streets. This list is not meant to be all-inclusive, but is a good starting point for homeowners, nursery and landscape professionals, landscape architects, and city planners looking for well-adapted, tough, and pest-resistant trees for Iowa communities. With that said, not all trees on this list will thrive in every landscape situation. Great care must be taken to carefully match trees to sites (including above- and below-ground spatial and environmental constraints) and to complement existing plants so that a diverse, functional, and attractive tree canopy can be created and maintained. Finally, conifers (excepting a few deciduous conifers) are generally inappropriate for use along city streets and therefore are not included here. Tree (species and notable cultivars) Height/Width Growth Habit Acer campestre – hedge maple 'JFS Shichtel 2' (Streetside Maple) 35'/18' Narrow oval Acer freemanii – Freeman maple 'Jeffersred' (Autumn Blaze Maple) 50'/40' Broad oval 'AF#1' (Firefall Maple) 50'/35' Upright oval 'Marmo' 55'/45' Upright oval 'Sienna' (Sienna Glen Maple) 50'/35' Pyramidal Acer miyabei – Miyabe maple 'Morton' (State Street Maple) 50'/35' Upright oval Acer nigrum – black maple 60'/60' Round spreading Acer rubrum – red maple 'JFS-KW78' (Armstrong Gold Maple) 40'/12' Narrow upright 'Franksred' (Red Sunset Maple) 45'/35' Upright oval 'Frank Jr.' (Redpointe Maple) 45'/30' Broad pyramidal Tree -

POISON IVY – Toxicodendron Radicans Whenever You Are in the Woods You Need to Be Aware of What Poison Ivy Looks Like

4-H FORESTRY JUDGING HANDBOOK SECTION I - TREE IDENTIFICATION By: Steven R. Patrick Agriculture & Natural Resources Agent Habersham County – North District INTRODUCTION TO TREE ID Identifying trees is an important part of Forestry Judging and also Dendrology. There are several things to keep in mind when you are out looking at trees to help you in making your guess as to what you’ve found: 1. Location – Piedmont (here), Mountains, or Coastal Plain? 2. Topography & Habitat – on top of a ridge or down by a creek for example? 3. Types of leaves – simple vs compound? 4. Type of bark, fruit, flowers, buds, etc. Getting all the possible information you have in the environment around you will help you in your quest to correctly identify the tree in front of you. Lets look at some simple terms used in identifying trees: Leaves are either simple or compound. A simple leaf is a leaf with a single blade, while a compound leaf is composed of 2 or more leaflets. You can usually look for a bud forming at the base of a leaf to tell what is a leaf and what is a leaflet when you’re starting out. Other important features to look for in trees are: leaf shape, venation, arrangement, fruit, twig, or bud types. The pictorial guides below should help you in learning important terms & tree features. 2 3 4 5 Photographs & Key Identification Features of GA Trees 1. POISON IVY – Toxicodendron radicans Whenever you are in the woods you need to be aware of what poison ivy looks like. -

Horticulture and Aesthetics of HYBRID OAKS Bykenasmus

HoRTICULTURE AND AESTHETics OF HYBRID OAKS byKenAsmus • My interest with hybrid oaks began purely by accident. While collecting acorns I noticed a tree similar to bur oak in characteristics only having white flakey bark and lobed leaves. I tried to stay away from the perimeter of this tree so as to not mix its acorns with that of a nearby bur oak. Due to a large bull on the other side of the fence, I wasn't paying close enough attention and probably collected a few from this tree. The following year I no ticed a few seedlings that were nearly twice as tall. By the second year two seedlings reached 5 feet. The next time I collected, I harvested only from this tree and grew them with the parent species. Again, the seedlings were more vigorous and seemed like a cross between white and bur oak. This hybrid is called Bebbs oak and is found throughout Michigan. It only took 6 years for these seedlings to fruit. They have bur oak type acorns with white oak foliage and look consistently identical to each other and strongly resemble the parent tree. Since my interest with oaks began with looking for sweet acorns, the "years to seed bear ing age" made breeding oaks a long-term proposition. For instance, white oak is sup posed to take 25 years to fruit. The hybrids seem to be a shortcut. Fortunately, I met Miguel Marquez of Texas, who not only had the same interest in Quercus, but also started such a breeding project in the mid 1950's. -

Hybrid Oaks (Quercus Spp.) of Georgia K.D

Hybrid Oaks (Quercus spp.) of Georgia K.D. Coder Publication WSFNR-20-26A April 2020 Hybrid Oaks (Quercus spp.) of Georgia Dr. Kim D. Coder, Professor of Tree Biology & Health Care / University Hill Fellow University of Georgia Warnell School of Forestry & Natural Resources The native oaks of Georgia are many and varied. Each has the capacity to interbreed or hybridize with surrounding oak species which are close relatives. Georgia’s hybrid oaks can be difficult to identify due to much gene sharing, cross-breeding, and associated variable leaf and acorn appearance. This publication helps professionals appreciate and understand oak hybrids in Georgia. Oak Hybrids -- A Success Strategy One means of oak genetic variation is generated by hybridization, leading to population divergence and specialization. Hybridization occurs naturally and can evolve into stable, genetically distinct populations and even species. Hybridization can generate new combinations of adaptations, by transferring or combining phenotypic features. (Niklas 2016) Hybridization of oaks played a significant role in their evolution. (Petit et.al. 2003) In addition to oak appearance and form, hybridization has also provided resistance-sharing among oak species to combat pathogens. (Hauser et.al. 2017) Oaks have been long known to exchange gene sets across species boundaries through hybridization and backcrossing. (Crowl et.al. 2019) Introgression is backcrossing with the parent species, and can generate some level of fixation of gene sets and physical features. (Niklas 2016) Hybridization and introgression events in oaks have occurred often, and has helped to solidify traits and adaptations. (Crowl et.al. 2019) Closely related oaks with similar reproductive strategies and overlapping geographical ranges often hybridize naturally.