Stanley Kubrick Didactics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

WARM WARM Kerning by Eye for Perfectly Balanced Spacing

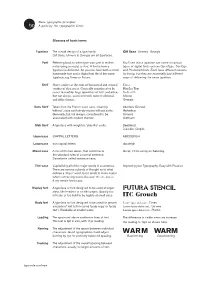

Basic typographic principles: A guide by The Typographic Circle Glossary of basic terms Typeface The overall design of a type family Gill Sans Univers Georgia Gill Sans, Univers & Georgia are all typefaces. Font Referring back to when type was cast in molten You’ll see that a typeface can come in various metal using a mould, or font. A font is how a types of digital font; such as OpenType, TrueType typeface is delivered. So you can have both a metal and Postscript fonts. Each have different reasons handmade font and a digital font file of the same for being, but they are essentially just different typeface, e.g Times or Futura. ways of delivering the same typeface. Serif Short strokes at the ends of horizontal and vertical Times strokes of characters. Generally considered to be Hoefler Text easier to read for large quantities of text, and often, Baskerville but not always, associated with more traditional Minion and older themes. Georgia Sans Serif Taken from the French word sans, meaning Akzidenz Grotesk ‘without’, sans serif simply means without serifs. Helvetica Generally, but not always, considered to be Univers associated with modern themes. Gotham Slab Serif A typeface with weightier, ‘slab-like’ serifs. Rockwell Lubalin Graph Uppercase CAPITAL LETTERS ABCDEFGH Lowercase non-capital letters abcdefgh Mixed-case A mix of the two above, that conforms to Great, it’ll be sunny on Saturday. the standard rules of a normal sentence. Sometimes called sentence-case. Title-case Capitalising all of the major words in a sentence. Improving your Typography: Easy with Practice There are various schools of thought as to what defines a ‘major’ word, but it tends to looks neater when connecting words like and, the, to, but, is & my remain lowercase. -

Summer Classic Film Series, Now in Its 43Rd Year

Austin has changed a lot over the past decade, but one tradition you can always count on is the Paramount Summer Classic Film Series, now in its 43rd year. We are presenting more than 110 films this summer, so look forward to more well-preserved film prints and dazzling digital restorations, romance and laughs and thrills and more. Escape the unbearable heat (another Austin tradition that isn’t going anywhere) and join us for a three-month-long celebration of the movies! Films screening at SUMMER CLASSIC FILM SERIES the Paramount will be marked with a , while films screening at Stateside will be marked with an . Presented by: A Weekend to Remember – Thurs, May 24 – Sun, May 27 We’re DEFINITELY Not in Kansas Anymore – Sun, June 3 We get the summer started with a weekend of characters and performers you’ll never forget These characters are stepping very far outside their comfort zones OPENING NIGHT FILM! Peter Sellers turns in not one but three incomparably Back to the Future 50TH ANNIVERSARY! hilarious performances, and director Stanley Kubrick Casablanca delivers pitch-dark comedy in this riotous satire of (1985, 116min/color, 35mm) Michael J. Fox, Planet of the Apes (1942, 102min/b&w, 35mm) Humphrey Bogart, Cold War paranoia that suggests we shouldn’t be as Christopher Lloyd, Lea Thompson, and Crispin (1968, 112min/color, 35mm) Charlton Heston, Ingrid Bergman, Paul Henreid, Claude Rains, Conrad worried about the bomb as we are about the inept Glover . Directed by Robert Zemeckis . Time travel- Roddy McDowell, and Kim Hunter. Directed by Veidt, Sydney Greenstreet, and Peter Lorre. -

JEANNE MOREAU: NOUVELLE VAGUE and BEYOND February 25 - March 18, 1994

The Museum of Modern Art For Immediate Release February 1994 JEANNE MOREAU: NOUVELLE VAGUE AND BEYOND February 25 - March 18, 1994 A film retrospective of the legendary French actress Jeanne Moreau, spanning her remarkable forty-five year career, opens at The Museum of Modern Art on February 25, 1994. JEANNE MOREAU: NOUVELLE VAGUE AND BEYOND traces the actress's steady rise from the French cinema of the 1950s and international renown as muse and icon of the New Wave movement to the present. On view through March 18, the exhibition shows Moreau to be one of the few performing artists who both epitomize and transcend their eras by the originality of their work. The retrospective comprises thirty films, including three that Moreau directed. Two films in the series are United States premieres: The Old Woman Mho Wades in the Sea (1991, Laurent Heynemann), and her most recent film, A Foreign Field (1993, Charles Sturridge), in which Moreau stars with Lauren Bacall and Alec Guinness. Other highlights include The Queen Margot (1953, Jean Dreville), which has not been shown in the United States since its original release; the uncut version of Eva (1962, Joseph Losey); the rarely seen Mata Hari, Agent H 21 (1964, Jean-Louis Richard), and Joanna Francesa (1973, Carlos Diegues). Alternately playful, seductive, or somber, Moreau brought something truly modern to the screen -- a compelling but ultimately elusive persona. After perfecting her craft as a principal member of the Comedie Frangaise and the Theatre National Populaire, she appeared in such films as Louis Malle's Elevator to the Gallows (1957) and The Lovers (1958), the latter of which she created a scandal with her portrayal of an adultress. -

Al Pacino Receives Bfi Fellowship

AL PACINO RECEIVES BFI FELLOWSHIP LONDON – 22:30, Wednesday 24 September 2014: Leading lights from the worlds of film, theatre and television gathered at the Corinthia Hotel London this evening to see legendary actor and director, Al Pacino receive a BFI Fellowship – the highest accolade the UK’s lead organisation for film can award. One of the world’s most popular and iconic stars of stage and screen, Pacino receives a BFI Fellowship in recognition of his outstanding achievement in film. The presentation was made this evening during an exclusive dinner hosted by BFI Chair, Greg Dyke and BFI CEO, Amanda Nevill, sponsored by Corinthia Hotel London and supported by Moët & Chandon, the official champagne partner of the Al Pacino BFI Fellowship Award Dinner. Speaking during the presentation, Al Pacino said: “This is such a great honour... the BFI is a wonderful thing, how it keeps films alive… it’s an honour to be here and receive this. I’m overwhelmed – people I’ve adored have received this award. I appreciate this so much, thank you.” BFI Chair, Greg Dyke said: “A true icon, Al Pacino is one of the greatest actors the world has ever seen, and a visionary director of stage and screen. His extraordinary body of work has made him one of the most recognisable and best-loved stars of the big screen, whose films enthral and delight audiences across the globe. We are thrilled to honour such a legend of cinema, and we thank the Corinthia Hotel London and Moët & Chandon for supporting this very special occasion.” Alongside BFI Chair Greg Dyke and BFI CEO Amanda Nevill, the Corinthia’s magnificent Ballroom was packed with talent from the worlds of film, theatre and television for Al Pacino’s BFI Fellowship presentation. -

The Inventory of the Richard Roud Collection #1117

The Inventory of the Richard Roud Collection #1117 Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center ROOD, RICHARD #1117 September 1989 - June 1997 Biography: Richard Roud ( 1929-1989), as director of both the New York and London Film Festivals, was responsible for both discovering and introducing to a wider audience many of the important directors of the latter half th of the 20 - century (many of whom he knew personally) including Bernardo Bertolucci, Robert Bresson, Luis Buiiuel, R.W. Fassbinder, Jean-Luc Godard, Werner Herzog, Terry Malick, Ermanno Ohni, Jacques Rivette and Martin Scorsese. He was an author of books on Jean-Marie Straub, Jean-Luc Godard, Max Ophuls, and Henri Langlois, as well as the editor of CINEMA: A CRITICAL DICTIONARY. In addition, Mr. Roud wrote extensive criticism on film, the theater and other visual arts for The Manchester Guardian and Sight and Sound and was an occasional contributor to many other publications. At his death he was working on an authorized biography of Fran9ois Truffaut and a book on New Wave film. Richard Roud was a Fulbright recipient and a Chevalier in the Legion of Honor. Scope and contents: The Roud Collection (9 Paige boxes, 2 Manuscript boxes and 3 Packages) consists primarily of book research, articles by RR and printed matter related to the New York Film Festival and prominent directors. Material on Jean-Luc Godard, Francois Truffaut and Henri Langlois is particularly extensive. Though considerably smaller, the Correspondence file contains personal letters from many important directors (see List ofNotable Correspondents). The Photographs file contains an eclectic group of movie stills. -

Film Essay for "Mccabe & Mrs. Miller"

McCabe & Mrs. Miller By Chelsea Wessels In a 1971 interview, Robert Altman describes the story of “McCabe & Mrs. Miller” as “the most ordinary common western that’s ever been told. It’s eve- ry event, every character, every west- ern you’ve ever seen.”1 And yet, the resulting film is no ordinary western: from its Pacific Northwest setting to characters like “Pudgy” McCabe (played by Warren Beatty), the gun- fighter and gambler turned business- man who isn’t particularly skilled at any of his occupations. In “McCabe & Mrs. Miller,” Altman’s impressionistic style revises western events and char- acters in such a way that the film re- flects on history, industry, and genre from an entirely new perspective. Mrs. Miller (Julie Christie) and saloon owner McCabe (Warren Beatty) swap ideas for striking it rich. Courtesy Library of Congress Collection. The opening of the film sets the tone for this revision: Leonard Cohen sings mournfully as the when a mining company offers to buy him out and camera tracks across a wooded landscape to a lone Mrs. Miller is ultimately a captive to his choices, una- rider, hunched against the misty rain. As the unidenti- ble (and perhaps unwilling) to save McCabe from his fied rider arrives at the settlement of Presbyterian own insecurities and herself from her opium addic- Church (not much more than a few shacks and an tion. The nuances of these characters, and the per- unfinished church), the trees practically suffocate the formances by Beatty and Julie Christie, build greater frame and close off the landscape. -

The Philosophy of Stanley Kubrick the Philosophy of Popular Culture

THE PHILOSOPHY OF STANLEY KUBRICK The Philosophy of Popular Culture The books published in the Philosophy of Popular Culture series will illuminate and explore philosophical themes and ideas that occur in popular culture. The goal of this series is to demonstrate how philosophical inquiry has been reinvigo- rated by increased scholarly interest in the intersection of popular culture and philosophy, as well as to explore through philosophical analysis beloved modes of entertainment, such as movies, TV shows, and music. Philosophical con- cepts will be made accessible to the general reader through examples in popular culture. This series seeks to publish both established and emerging scholars who will engage a major area of popular culture for philosophical interpretation and examine the philosophical underpinnings of its themes. Eschewing ephemeral trends of philosophical and cultural theory, authors will establish and elaborate on connections between traditional philosophical ideas from important thinkers and the ever-expanding world of popular culture. Series Editor Mark T. Conard, Marymount Manhattan College, NY Books in the Series The Philosophy of Stanley Kubrick, edited by Jerold J. Abrams The Philosophy of Martin Scorsese, edited by Mark T. Conard The Philosophy of Neo-Noir, edited by Mark T. Conard Basketball and Philosophy, edited by Jerry L. Walls and Gregory Bassham THE PHILOSOPHY OF StaNLEY KUBRICK Edited by Jerold J. Abrams THE UNIVERSITY PRESS OF KENTUCKY Publication of this volume was made possible in part by a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities. Copyright © 2007 by The University Press of Kentucky Scholarly publisher for the Commonwealth, serving Bellarmine University, Berea College, Centre College of Kentucky, Eastern Kentucky University, The Filson Historical Society, Georgetown College, Kentucky Historical Society, Kentucky State University, Morehead State University, Murray State University, Northern Kentucky University, Transylvania University, University of Kentucky, University of Louisville, and Western Kentucky University. -

It's a Conspiracy

IT’S A CONSPIRACY! As a Cautionary Remembrance of the JFK Assassination—A Survey of Films With A Paranoid Edge Dan Akira Nishimura with Don Malcolm The only culture to enlist the imagination and change the charac- der. As it snows, he walks the streets of the town that will be forever ter of Americans was the one we had been given by the movies… changed. The banker Mr. Potter (Lionel Barrymore), a scrooge-like No movie star had the mind, courage or force to be national character, practically owns Bedford Falls. As he prepares to reshape leader… So the President nominated himself. He would fill the it in his own image, Potter doesn’t act alone. There’s also a board void. He would be the movie star come to life as President. of directors with identities shielded from the public (think MPAA). Who are these people? And what’s so wonderful about them? —Norman Mailer 3. Ace in the Hole (1951) resident John F. Kennedy was a movie fan. Ironically, one A former big city reporter of his favorites was The Manchurian Candidate (1962), lands a job for an Albu- directed by John Frankenheimer. With the president’s per- querque daily. Chuck Tatum mission, Frankenheimer was able to shoot scenes from (Kirk Douglas) is looking for Seven Days in May (1964) at the White House. Due to a ticket back to “the Apple.” Pthe events of November 1963, both films seem prescient. He thinks he’s found it when Was Lee Harvey Oswald a sleeper agent, a “Manchurian candidate?” Leo Mimosa (Richard Bene- Or was it a military coup as in the latter film? Or both? dict) is trapped in a cave Over the years, many films have dealt with political conspira- collapse. -

HJR 23.1 Sadoff

38 The Henry James Review Appeals to Incalculability: Sex, Costume Drama, and The Golden Bowl By Dianne F. Sadoff, Miami University Sex is the last taboo in film. —Catherine Breillat Today’s “meat movie” is tomorrow’s blockbuster. —Carol J. Clover When it was released in May 2001, James Ivory’s film of Henry James’s final masterpiece, The Golden Bowl, received decidedly mixed reviews. Kevin Thomas calls it a “triumph”; Stephen Holden, “handsome, faithful, and intelligent” yet “emotionally distanced.” Given the successful—if not blockbuster—run of 1990s James movies—Jane Campion’s The Portrait of a Lady (1996), Agniezka Holland’s Washington Square (1997), and Iain Softley’s The Wings of the Dove (1997)—the reviewers, as well as the fans, must have anticipated praising The Golden Bowl. Yet the film opened in “selected cities,” as the New York Times movie ads noted; after New York and Los Angeles, it showed in university towns and large urban areas but not “at a theater near you” or at “theaters everywhere.” Never mind, however, for the Merchant Ivory film never intended to be popular with the masses. Seeking a middlebrow audience of upper-middle-class spectators and generally intelligent filmgoers, The Golden Bowl aimed to portray an English cultural heritage attractive to Anglo-bibliophiles. James’s faux British novel, however, is paradoxically peopled with foreigners: American upwardly mobile usurpers, an impoverished Italian prince, and a social-climbing but shabby ex- New York yentl. Yet James’s ironic portrait of this expatriate culture, whose characters seek only to imitate their Brit betters—if not in terms of wealth and luxury, at least in social charm and importance—failed to seem relevant to viewers The Henry James Review 23 (2002): 38–52. -

Press Release 12 January 2016

Press Release 12 January 2016 (For immediate release) SIDNEY POITIER TO BE HONOURED WITH BAFTA FELLOWSHIP London,12 January 2016: The British Academy of Film and Television Arts will honour Sir Sidney Poitier with the Fellowship at the EE British Academy Film Awards on Sunday 14 February. Awarded annually, the Fellowship is the highest accolade bestowed by BAFTA upon an individual in recognition of an outstanding and exceptional contribution to film, television or games. Fellows previously honoured for their work in film include Charlie Chaplin, Alfred Hitchcock, Steven Spielberg, Sean Connery, Elizabeth Taylor, Stanley Kubrick, Anthony Hopkins, Laurence Olivier, Judi Dench, Vanessa Redgrave, Christopher Lee, Martin Scorsese, Alan Parker and Helen Mirren. Mike Leigh received the Fellowship at last year’s Film Awards. Sidney Poitier said: “I am extremely honored to have been chosen to receive the Fellowship and my deep appreciation to the British Academy for the recognition.” Amanda Berry OBE, Chief Executive of BAFTA, said: “I’m absolutely thrilled that Sidney Poitier is to become a Fellow of BAFTA. Sidney is a luminary of film whose outstanding talent in front of the camera, and important work in other fields, has made him one of the most important figures of his generation. His determination to pursue his dreams is an inspirational story for young people starting out in the industry today. By recognising Sidney with the Fellowship at the Film Awards on Sunday 14 February, BAFTA will be honouring one of cinema’s true greats.” Sir Sidney Poitier’s award-winning career features six BAFTA nominations, including one BAFTA win, and a British Academy Britannia Award for Lifetime Contribution to International Film. -

The Musical Contexts GCSE Music Study and Revision Guide For

GCSE MUSIC – FILM MUSIC S T U D Y A N D REVISION GUIDE The Musical Contexts GCSE Music Study and Revision Guide for Film Music Designed to support: Eduqas GCSE Music – Area of Study 3: Film Music OCR GCSE Music – Area of Study 4: Film Music Pearson Edexcel GCSE Music – Area of Study: Music for Stage and Screen P a g e 1 o f 32 © WWW.MUSICALCONTEXTS.CO.UK GCSE MUSIC – FILM MUSIC S T U D Y A N D REVISION GUIDE The Purpose of Film Music Film Music is a type of DESCRIPTIVE MUSIC that represents a mood, story, scene or character through music; it is designed to support the action and emotions of the film on screen. Film music serves many different purposes including: 1. To create or enhance a mood 2. To function as a LEITMOTIF 3. To link one scene to another providing continuity 4. To emphasise a gesture (known as MICKEY-MOUSING) 5. To give added commercial impetus 6. To provide unexpected juxtaposition or to provide irony 7. To illustrate geographic location or historical period 8. To influence the pacing of a scene 1. To create or enhance a mood Music aids (and is sometimes essential to effect) the suspension of our disbelief: film attempts to convince us that what we are seeing is really happening and music can help break down any resistance we might have. It can also comment directly on the film, telling us how to respond to the action. Music can also enhance a dramatic effect: the appearance of a monster in a horror film, for example, rarely occurs without a thunderous chord! Sound effects (like explosions and gunfire) can be incorporated into the film soundtrack to create a feeling of action and emotion, particularly in war films. -

The Hirschfeld Century: the Art of Al Hirschfeld May 22, 2015 - October 12, 2015

The Hirschfeld Century: the Art of Al Hirschfeld May 22, 2015 - October 12, 2015 Lubova Yarovaya, 1929 Ink on board Laurel and Hardy © The Al Hirschfeld Foundation. Ink, watercolor, collage wallpaper sample, and www.AlHirschfeldFoundation.org photograph, 1928 © The Al Hirschfeld Foundation. www.AlHirschfeldFoundation.org Charlie Chaplin, “A Man with Both Feet in the Clouds,” 1942 Ink on board Sunnyside, 1927 © The Al Hirschfeld Foundation. Lithograph poster www.AlHirschfeldFoundation.org © The Al Hirschfeld Foundation. www.AlHirschfeldFoundation.org Nina’s Revenge, 1966 Charles De Gaulle, Ink on board Gouache on board, 1945 © The Al Hirschfeld Foundation. © The Al Hirschfeld Foundation. www.AlHirschfeldFoundation.org www.AlHirschfeldFoundation.org Tony Curtis and Sidney Poitier in The Defiant Ones, 1958 Ruby Keeler in No, No Nanette, 1971 Ink on board Ink on board © The Al Hirschfeld Foundation. © The Al Hirschfeld Foundation. www.AlHirschfeldFoundation.org www.AlHirschfeldFoundation.org All images must have the following credit line: © The Al Hirschfeld Foundation. www.AlHirschfeldFoundation.org Richard Kiley in Man of La Mancha, 1977 Self portrait, 1985 Ink on board Ink on board Harvard Art Museums/Fogg Museum, The Melvin R. The Melvin R. Seiden Collection, Houghton Library, Seiden Collection, 1988.444 Harvard University © The Al Hirschfeld Foundation. © The Al Hirschfeld Foundation. www.AlHirschfeldFoundation.org www.AlHirschfeldFoundation.org Mikhail Baryshnikov in Metamorphosis, 1989 Ink on board The Melvin R. Seiden Collection, Houghton Library, Harvard University © The Al Hirschfeld Foundation. www.AlHirschfeldFoundation.org Jerry Orbach in 42nd Street, 1980 Ink on board © The Al Hirschfeld Foundation. www.AlHirschfeldFoundation.org All images must have the following credit line: © The Al Hirschfeld Foundation.