Paradise Regained in Nicholas Nickleby

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE PICKWICK PAPERS Required Reading for the Dickens Universe

THE PICKWICK PAPERS Required reading for the Dickens Universe, 2007: * Auden, W. H. "Dingley Dell and the Fleet." The Dyer's Hand and Other Essays. New York: Random House, 1962. 407-28. * Marcus, Steven. "The Blest Dawn." Dickens: From Pickwick to Dombey. New York: Basic Books, 1965. 13-53. * Patten, Robert L. Introduction. The Pickwick Papers. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1972. 11-30. * Feltes, N. N. "The Moment of Pickwick, or the Production of a Commodity Text." Literature and History: A Journal for the Humanities 10 (1984): 203-217. Rpt. in Modes of Production of Victorian Novels. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1986. * Chittick, Kathryn. "The qualifications of a novelist: Pickwick Papers and Oliver Twist." Dickens and the 1830s. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1990. 61-91. Recommended, but not required, reading: Marcus, Steven."Language into Structure: Pickwick Revisited," Daedalus 101 (1972): 183-202. Plus the sections on The Pickwick Papers in the following works: John Bowen. Other Dickens : Pickwick to Chuzzlewit. Oxford, U.K.; New York: Oxford UP, 2000. Grossman, Jonathan H. The Art of Alibi: English Law Courts and the Novel. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins UP, 2002. Woloch, Alex. The One vs. The Many: Minor Characters and the Space of the Protagonist in the Novel. Princeton: Princeton UP, 2003. 1 SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY Compiled by Hillary Trivett May, 1991 Updated by Jessica Staheli May, 2007 For a comprehensive bibliography of criticism before 1990, consult: Engel, Elliot. Pickwick Papers: An Annotated Bibliography. New York: Garland Publishing Inc., 1990. CRITICISM Auden, W. H. "Dingley Dell and the Fleet." The Dyer's Hand and Other Essays. New York: Random House, 1962. -

The Treatment of Children in the Novels of Charles

THE TREATMENT OF CHILDREN IN THE NOVELS OF CHARLES DICKENS A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF ATLANTA UNIVERSITY IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS BY CLEOPATRA JONES DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH ATLANTA, GEORGIA AUGUST 1948 ? C? TABLE OF CONTENTS % Pag® PREFACE ii CHAPTER I. REASONS FOR DICKENS' INTEREST IN CHILDREN ....... 1 II. TYPES OF CHILDREN IN DICKENS' NOVELS 10 III. THE FUNCTION OF CHILDREN IN DICKENS' NOVELS 20 IV. DICKENS' ART IN HIS TREATMENT OF CHILDREN 33 SUMMARY 46 BIBLIOGRAPHY 48 PREFACE The status of children in society has not always been high. With the exception of a few English novels, notably those of Fielding, child¬ ren did not play a major role in fiction until Dickens' time. Until the emergence of the Industrial Revolution an unusual emphasis had not been placed on the status of children, and the emphasis that followed was largely a result of the insecure and often lamentable position of child¬ ren in the new machine age. Since Dickens wrote his novels during this period of the nineteenth century and was a pioneer in the employment of children in fiction, these facts alone make a study of his treatment of children an important one. While a great deal has been written on the life and works of Charles Dickens, as far as the writer knows, no intensive study has been made of the treatment of children in his novels. All attempts have been limited to chapters, or more accurately, to generalized statements in relation to his life and works. -

Mimesis As Subject in Nicholas Nickleby

Juliet Me Master Mimesis as Subject in Nicholas Nickleby "There are dark shadows on the earth, but its lights are stronger in the contrast," Dickens had written at the end of his first novel. (pp. 799) 1 By and large, in Pickwick he had dealt with the light. Pickwick himself was the sun, a source of light and joy in his world, which had many other similar beacons in the persons of Tony, Sam, Wardle, and the others. It is a world which in its way is even more "light, bright and sparkling" than Pride and Prejudice, a world bursting with energy, cheer, and joy. It is, of course, not without its shadows, but they are the shadows which function as intensifiers of the light. In Oliver Twist, as though the young Dickens were testing his powers in one mode after another, he created a world in which the shadows predominate. The workhouse, and Fagin's dens, and the dim foetid alleys of underworld London, form the essential and memorable ambiance of Oliver, and the airy streets of Penton ville and the sunshine of the May lies become merely the assisting gleams that emphasize the dark. Dickens was flexing his muscles by deliberately writing a second novel that was to be as different from his first as the mind of a single creator could make it. As Pickwick was middle~aged, and fat, and jolly, and financially secure, so Oliver was to be a child, and starved, and terrorised, and utterly vulnerable. As Pickwick celebrates laughter, and eating and drinking, and fatness, Oliver Twist was to turn the tables: the irrepress~ ible and joyful mirth of Tony Weller becomes transformed to the heartless cacchinations of Charley Bates, whose sense of humour is most stimulated by the pains of others. -

Nicholas Nickleby

LEVEL 4 Teacher’s notes Teacher Support Programme Nicholas Nickleby Charles Dickens Chapters 3–4: Nicholas finds life at Dotheboys hard and is appalled by the cruel treatment given the to boys and to Smike, who runs away. Nicholas has a fistfight with Squeers and leaves the school. On his way back to London, Nicholas finds Smike and agrees to take him with him. Nicholas finds cheap lodgings in London and a job as a private French teacher. When Nicholas visits his mother and sister, he overhears his uncle telling them that he is a thief who has stolen a ring from Squeers and has run away with one of the children. Nicholas argues with Ralph and tries to defend himself from all the accusations but finally decides to leave London once again so as to protect his mother and sister. Summary Chapters 5–6: In London, Kate finds a job as Mrs Wititterly’s companion. Unfortunately, one of Ralph’s best The Nicklebys (Nicholas, his mother, sister Kate) are customers, Sir Mulberry Hawk, likes Kate and insists on penniless after the death of Mr Nickleby. In their poverty spending time with her despite her turning him down. and desperation they seek help from Nicholas’s Uncle Kate asks Ralph for help but he refuses to lose his best Ralph, a mean-spirited, cruel moneylender. Nicholas’s client. Newman Noggs overhears the conversation and independent attitude angers Ralph and Nicholas is sent writes to Nicholas, who decides to come back to London. away to Dotheboys Hall to teach. He is upset by the Nicholas fights Sir Mulberry and orders him to stay away mistreatment of the children there by Headmaster from his sister. -

Test Your Knowledge: a Dickens of a Celebration!

A Dickens of a Celebration atKinson f. KathY n honor of the bicentennial of Charles dickens’ birth, we hereby Take the challenge! challenge your literary mettle with a quiz about the great Victorian Iwriter. Will this be your best of times, or worst of times? Good luck! This novel was Dickens and his wife, This famous writer the first of Dickens’ Catherine, had this was a good friend 1 romances. 5 many children; 8 of Dickens and some were named after his dedicated a book to him. (a) David Copperfield favorite authors. (b) Martin Chuzzlewit (a) Mark twain (c) Nicholas Nickleby (a) ten (b) emily Bronte (b) five (c) hans christian andersen (c) nine Many of Dickens’ books were cliffhangers, Where was 2 published in monthly The conditions of the Dickens buried? installments. In 1841, readers in working class are a Britain and the U.S. anxiously 9 common theme in awaited news of the fate of the 6 (a) Portsmouth, england Dickens’ books. Why? pretty protagonist in this novel. (where he was born) (a) he had to work in a (b) Poet’s corner, westminster (a) Little Dorrit warehouse as a boy to abbey, London (b) A Tale of Two Cities help get his family out of (c) isles of scilly (c) The Old Curiosity Shop debtor’s prison. (b) his father worked in a livery and was This amusement This was an early mistreated there. park in Chatham, pseudonym used (c) his mother worked as England, is 3 by Dickens. a maid as a teenager and named10 after Dickens. -

David Copperfield

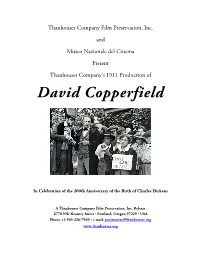

Thanhouser Company Film Preservation, Inc. and Museo Nazionale del Cinema Present Thanhouser Company’s 1911 Production of David Copperfield In Celebration of the 200th Anniversary of the Birth of Charles Dickens A Thanhouser Company Film Preservation, Inc. Release 8770 NW Kearney Street • Portland, Oregon 97229 • USA Phone +1-503-226-7960 • e-mail: [email protected] www.thanhouser.org Press Kit: David Copperfield (1911) Credits Produced by ................................... Edwin Thanhouser Directed by .................................... George O. Nichols Starring .......................................... Flora Foster (David Copperfield as a young boy) Ed Genung (David Copperfield as a young man) Marie Eline (Little Em’ly as a young girl) Florence LaBadie (Em’ly as a young woman) Mignon Anderson (Dora) Marguerite Snow (Agnes) James Cruze (Steerforth) William Russell (Ham) New and Original Music by ........... Dr. Philip Carli (Rochester, New York) Commentary by ............................. Professor Joss Marsh (Indiana University/Kent-MOMI) 1911 USA Release .......................... Thanhouser Company (New Rochelle, New York) 1911 European Distribution .......... Western Import Company, Ltd. (London, England) 1959 Preservation ........................... Museo Nazionale del Cinema (Torino, Italy) 2012 Restoration ............................ Museo Nazionale del Cinema (Torino, Italy) 2012 DVD Release ........................ Thanhouser Company Film Preservation, Inc. (Portland, Oregon) Black and White, 1.33 : 1 aspect ratio, -

A DICKENS COMPANION Macmillan Literary Companions

A DICKENS COMPANION Macmillan Literary Companions J. R. Hammond AN H. G. WELLS COMPANION AN EDGAR ALLAN POE COMPANION A GEORGE ORWELL COMPANION A ROBERT LOUIS STEVENSON COMPANION John Spencer Hill A COLERIDGE COMPANION Norman Page A DICKENS COMPANION A KIPLING COMPANION F. B. Pinion A HARDY COMPANION A BRONTE COMPANION A JANE AUSTEN COMPANION A D. H. LAWRENCE COMPANION A WORDSWORTH COMPANION A GEORGE ELIOT COMPANION A DICKENS COMPANION NORMAN PAGE ~ MACMILLAN © Norman Page 1984 Softcover reprint of the hardcover 1st edition 1984 All rights reserved. No reproduction, copy or transmission of this publication may be made without written permission. No paragraph of this publication may be reproduced, copied or transmitted save with written permission or in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, or under the terms of any licence permitting limited copying issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency, 90 Tottenham Court Road, London WIP 9HE. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages. First published 1984 by MACMILLAN PRESS LTD Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire RG21 2XS and London Companies and representatives throughout the world ISBN 978-1-349-06006-1 ISBN 978-1-349-06004-7 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-1-349-06004-7 A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. 10 98 7 65432 03 02 0 I 00 99 98 97 96 95 To Valerie and Campbell Purton, and the Infant Phenomena Dinah and Tom Contents List of Plates IX Preface XI Abbreviations XV A Dickens Chronology The Dickens Circle 19 DICKENS' WRITINGS 53 Sketches by Boz:. -

Dickens Brochure

Message from John ne of the many benefits that came to us as students at the University of Oklahoma and Mary Nichols during the 1930s was a lasting appreciation for the library. It was a wonderful place, not as large then as now, but the library was still the most impressive building on campus. Its rich wood paneling, cathedral-like reading room, its stillness, and what seemed like acres of books left an impression on even the most impervious undergraduates. Little did we suspect that one day we would come to appreciate this great OOklahoma resource even more. Even as students we sensed that the University Library was a focal point on campus. We quickly learned that the study and research that went on inside was important and critical to the success of both faculty and students. After graduation, reading and enjoyment of books, especially great literature, continued to be important to us and became one of our lifelong pastimes. We have benefited greatly from our past association with the University of Oklahoma Libraries and it is now our sincere hope that we might share our enjoyment of books with others. It gives us great pleasure to make this collection of Charles Dickens’ works available at the University of Oklahoma Libraries. “Even as As alumni of this great university, we also take pride in the knowledge that the library remains at the students center of campus activity. It is gratifying to know that in this electronic age, university faculty and students still we sensed that find the library a useful place for study and recreation. -

The Inorganic Aesthetic in Dickens¬タルs Our Mutual Friend

7KH,QRUJDQLF$HVWKHWLFLQ'LFNHQV·V2XU0XWXDO)ULHQG HdHOLNNROت\$ 3DUWLDO$QVZHUV-RXUQDORI/LWHUDWXUHDQGWKH+LVWRU\RI,GHDV9ROXPH 1XPEHU-DQXDU\SS $UWLFOH 3XEOLVKHGE\-RKQV+RSNLQV8QLYHUVLW\3UHVV '2, KWWSVGRLRUJSDQ )RUDGGLWLRQDOLQIRUPDWLRQDERXWWKLVDUWLFOH KWWSVPXVHMKXHGXDUWLFOH Access provided by Bilkent Universitesi (15 Nov 2016 08:32 GMT) The Inorganic Aesthetic in Dickens’s Our Mutual Friend Ays¸e Çelikkol Bilkent University Featuring characters and subplots almost too numerous to follow, Dick- ens’s novels attest to the genre’s penchant for variety. At the same time, they famously rely on repetition, both at the sentence level and themati- cally. Recurrent motifs abound: imprisonment in Little Dorrit, guilt and confession in Great Expectations, and chaos and decay in Bleak House. Repetition in Our Mutual Friend is potent enough to render the novel uncanny, with doubles becoming indistinct from one another at various points, and the plot unfolding through versions of events such as drown- ing; the novel overflows with fixed memes, which are reiterated, almost mechanically, in various situations. Someone must always risk drowning in the river, be it Gaffer Hexam, Eugene Wrayburn, John Harmon, Rogue Riderhood, or Bradley Headstone. Some young woman is bound to be the “boofer lady,” be it Lizzie or Bella (324). As the plot retraces its own steps, we confront a world in which individuals appear interchangeable, and the power of individuation is temporarily suspended. I propose that this formal structure moves the novel away from the well-trodden terrain of organic form, one of the most commonplace liter- ary ideals of the period, which the Victorians inherited from the British Romantics. Organic form consists of the interdependence of parts that are unified but distinct; it offers, in Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s words, “unity in the many” (1995c: 510). -

OUR MUTUAL FRIEND by Charles Dickens

OUR MUTUAL FRIEND by Charles Dickens THE AUTHOR Charles Dickens (1812-1870) was the second of eight children in a family plagued by debt. When he was twelve, his father was thrown into debtors’ prison, and Charles was forced to quit school and work in a shoe-dye factory. These early experiences gave him a sympathy for the poor and downtrodden, along with an acute sense of social justice. At the age of fifteen, he became a clerk in a law firm, and later worked as a newspaper reporter. He published his first fiction in 1836 - a series of character sketches called Sketches by Boz. The work was well-received, but its reception was nothing compared to the international acclaim he received with the publication of The Pickwick Papers in the following year. After this early blush of success, Dickens took on the job as editor of Bentley’s Miscellany, a literary magazine in which a number of his early works were serialized, including Oliver Twist (1837-9) and Nicholas Nickleby (1838-9). He left to begin his own literary magazine, Master Humphrey’s Clock, in 1840, and over the next ten years published many of his most famous novels in serial form, including The Old Curiosity Shop (1840-1), A Christmas Carol (1844), and David Copperfield (1849-50), perhaps the most autobiographical of all his novels. Other works were serialized in Household Words between 1850 and 1859, including Bleak House (1852-3), which was then succeeded by All the Year Round, which he edited until his death in 1870, publishing such novels as A Tale of Two Cities (1859), Great Expectations (1860-1), and Our Mutual Friend (1864-5). -

The Naming of Characters in the Works of Charles Dickens

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln University of Nebraska Studies in Language, Literature, and Criticism English, Department of January 1917 THE NAMING OF CHARACTERS IN THE WORKS OF CHARLES DICKENS Elizabeth Hope Gordon The Technical High School Indianapolis Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/englishunsllc Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Gordon, Elizabeth Hope, "THE NAMING OF CHARACTERS IN THE WORKS OF CHARLES DICKENS" (1917). University of Nebraska Studies in Language, Literature, and Criticism. 5. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/englishunsllc/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the English, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Nebraska Studies in Language, Literature, and Criticism by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. UNIVERSITY OF NEBRASKA STUDIES IN LANGUAGE, LITERATURE, AND CRITICISM Number I THE NAMING OF CHARACTERS IN. THE WORKS OF CHARLES DICKENS BY ELIZABETH HOPE GORDON, A.M: Tetu'ker oj English, The Technical High School Indianapolis EPITOlUALCOtdMITTEE WUISE POUND, PH. D., Departmem 6f E1l!1lish H. B. ALEXANDER, PH. D., Department of Philosoph" F. W. S"ANFORD, PH. D., Department of Latill LINCOLN 1917 THE NAMING OF CHARACTERS IN THE WORKS OF CHARLES DICKENS Introduction An extensive examination of the names of characters in tlte works of the majority of nineteenth and twentieth century Qovelists would obviously be of little value, for the growjng tendency toward the commonplace in realism has necessitated tl}e selection of neutral names or names taken outright from a~tual persons. -

Bleak House: the Dark Heart of Charles Dickens 5 Biweekly Sessions: Every Other Saturday, April 28 – June 23 | 2:00–4:00 P.M

Bleak House: The Dark Heart of Charles Dickens 5 biweekly sessions: every other Saturday, April 28 – June 23 | 2:00–4:00 p.m. Led by Edward G. Pettit, Manager of Public Programs at the Rosenbach Charles Dickens’ Bleak House lives up to its title, exploring the bleakest parts of London and the dark desires of its inhabitants. The novel opens in fog, then takes the reader into the circuitous byways of the slum Tom-all-Alone’s and the through the interminable legal case of Jarndyce v. Jarndyce. With Dickens’ usual flair for names, we encounter Lady Dedlock, Inspector Bucket, Summerson, Skimpole, Tulkinghorn and Krook. Mysteries of identity and murder need to be solved before the end. Even spontaneous combustion makes an appearance as one character suddenly bursts into flame. Bleak House is the novel to read when you want to wander through the dark streets of Dickens’ imagination. Lady Dedlock by Mervyn Peake Edward G Pettit is the Manager of Public of Programs at the Rosenbach. In 2012, Pettit served as the Charles Dickens Ambassador for the Free Library of Philadelphia’s yearlong Bicentenary celebration of the author’s birth and wrote the Ebenezer Maxwell Mansion's 2013 mystery play, Twisted, in which he played Dickens. He has lectured widely on Dickens and given public readings of Dickens’ Christmas stories. For the Rosenbach, Pettit has taught many courses, including Dickens’ A Christmas Carol and Nicholas Nickleby. We will break the novel into four readings, covering each part in a session, then we’ll have a final fifth session for open discussion of the novel in its entirety.