The Naming of Characters in the Works of Charles Dickens

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Narrative Inquiry Into Chinese International Doctoral Students

Volume 16, 2021 NARRATIVE INQUIRY INTO CHINESE INTERNATIONAL DOCTORAL STUDENTS’ JOURNEY: A STRENGTH-BASED PERSPECTIVE Shihua Brazill Montana State University, Bozeman, [email protected] MT, USA ABSTRACT Aim/Purpose This narrative inquiry study uses a strength-based approach to study the cross- cultural socialization journey of Chinese international doctoral students at a U.S. Land Grant university. Historically, we thought of socialization as an institu- tional or group-defined process, but “journey” taps into a rich narrative tradi- tion about individuals, how they relate to others, and the identities that they carry and develop. Background To date, research has employed a deficit perspective to study how Chinese stu- dents must adapt to their new environment. Instead, my original contribution is using narrative inquiry study to explore cross-cultural socialization and mentor- ing practices that are consonant with the cultural capital that Chinese interna- tional doctoral students bring with them. Methodology This qualitative research uses narrative inquiry to capture and understand the experiences of three Chinese international doctoral students at a Land Grant in- stitute in the U.S. Contribution This study will be especially important for administrators and faculty striving to create more diverse, supportive, and inclusive academic environments to en- hance Chinese international doctoral students’ experiences in the U.S. Moreo- ver, this study fills a gap in existing research by using a strength-based lens to provide valuable practical insights for researchers, practitioners, and policymak- ers to support the unique cross-cultural socialization of Chinese international doctoral students. Findings Using multiple conversational interviews, artifacts, and vignettes, the study sought to understand the doctoral experience of Chinese international students’ experience at an American Land Grant University. -

Charles Dickens' Corruption and Idealization Personified in Oliver Twist

Western Oregon University Digital Commons@WOU Academic Excellence Showcase Proceedings Student Scholarship 2018-06-02 Charles Dickens’ Corruption and Idealization Personified in Oliver Twist Ellie Phillips Western Oregon University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wou.edu/aes Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Phillips, Ellie, "Charles Dickens’ Corruption and Idealization Personified in Oliver Twist" (2018). Academic Excellence Showcase Proceedings. 150. https://digitalcommons.wou.edu/aes/150 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at Digital Commons@WOU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Academic Excellence Showcase Proceedings by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@WOU. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]. Byrd 1 Ellie Byrd Dr. Lange ENG 218w Charles Dickens’ Corruption and Idealization Personified in Oliver Twist In Charles Dickens’ Oliver Twist, the depictions of corruption and virtue are prevalent throughout most of the novel and take the physical form in the city and the country. Oliver spends much of his time in London among criminals and the impoverished, and here is where Dickens takes the city of London and turns it into a dark and degraded place. Dickens’ London is inherently immoral and serves as a center for the corruption of mind and spirit which is demonstrated through the seedy scenes Dickens paints of London, the people who reside there, and by casting doubt in individuals who otherwise possess a decent moral compass. Furthermore, Dickens’ strict contrast of the country to these scenes further establishes the sinister presence of London. -

Appendix: Street Plans

Appendix: Street Plans Charles Dickens' birthplace. (Michael Allen) 113 114 Appendix The Hawke Street area as it is now, showing the site of number 16. (Michael Allen) Appendix 115 The Wish Street area as it is now, showing the site of the house occupied by the Dickens family. (Michael Allen) 116 Appendix Cleveland Street as it is now, showing the site of what was 10 Norfolk Street. (Michael Allen) Appendix 117 Site of 2 Ordnance Terrace. (Michael Allen) 118 Appendix Site of 18 StMary's Place, The Brook. (Michael Allen) Appendix 119 Site of Giles' House, Best Street. (Michael Allen) 120 Appendix Site of 16 Bayham Street. (Michael Allen) Appendix 121 Site of 4 Gower Street North. (Michael Allen) 122 Appendix Site of 37 Little College Street. (Michael Allen) Appendix 123 "'2 ~ <( Qj ftl ~ 0 ~ a; .......Q) ....... en ...., c .. ftl ...-' .. 0 ~ -....Q) .. u; 124 Appendix Site of 29 Johnson Street. (Michael Allen) Notes The place of publication is London unless otherwise stated. INTRODUCTION 1. 'Dickens's obscure childhood in pre-Forster biography', by Elliot Engel, in The Dickensian, 1976, pp. 3-12. 2. The letters of Charles Dickens, Pilgrim edition, Vol. 1: 1820-1839 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1965) p. 423. 3. In History, xlvii, no. 159, pp. 42-5. 4. The Pickwick Papers (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1972) p. 521. 5. John Forster, The life of Charles Dickens (Chapman & Hall, 1872-4) Vol. 3, p. 11. 6. Ibid., Vol. 1, p. 17. 1 PORTSMOUTH 1. Gladys Storey, Dickens and daughter (Muller, 1939) p. 31. 2, 'The Dickens ancestry: some new discoveries', in The Dickensian, 1949, pp. -

THE PICKWICK PAPERS Required Reading for the Dickens Universe

THE PICKWICK PAPERS Required reading for the Dickens Universe, 2007: * Auden, W. H. "Dingley Dell and the Fleet." The Dyer's Hand and Other Essays. New York: Random House, 1962. 407-28. * Marcus, Steven. "The Blest Dawn." Dickens: From Pickwick to Dombey. New York: Basic Books, 1965. 13-53. * Patten, Robert L. Introduction. The Pickwick Papers. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1972. 11-30. * Feltes, N. N. "The Moment of Pickwick, or the Production of a Commodity Text." Literature and History: A Journal for the Humanities 10 (1984): 203-217. Rpt. in Modes of Production of Victorian Novels. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1986. * Chittick, Kathryn. "The qualifications of a novelist: Pickwick Papers and Oliver Twist." Dickens and the 1830s. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1990. 61-91. Recommended, but not required, reading: Marcus, Steven."Language into Structure: Pickwick Revisited," Daedalus 101 (1972): 183-202. Plus the sections on The Pickwick Papers in the following works: John Bowen. Other Dickens : Pickwick to Chuzzlewit. Oxford, U.K.; New York: Oxford UP, 2000. Grossman, Jonathan H. The Art of Alibi: English Law Courts and the Novel. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins UP, 2002. Woloch, Alex. The One vs. The Many: Minor Characters and the Space of the Protagonist in the Novel. Princeton: Princeton UP, 2003. 1 SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY Compiled by Hillary Trivett May, 1991 Updated by Jessica Staheli May, 2007 For a comprehensive bibliography of criticism before 1990, consult: Engel, Elliot. Pickwick Papers: An Annotated Bibliography. New York: Garland Publishing Inc., 1990. CRITICISM Auden, W. H. "Dingley Dell and the Fleet." The Dyer's Hand and Other Essays. New York: Random House, 1962. -

Chivalry in Western Literature Richard N

Rollins College Rollins Scholarship Online Master of Liberal Studies Theses 2012 The nbU ought Grace of Life: Chivalry in Western Literature Richard N. Boggs Rollins College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.rollins.edu/mls Part of the English Language and Literature Commons, European History Commons, Medieval History Commons, and the Medieval Studies Commons Recommended Citation Boggs, Richard N., "The nbouU ght Grace of Life: Chivalry in Western Literature" (2012). Master of Liberal Studies Theses. 21. http://scholarship.rollins.edu/mls/21 This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by Rollins Scholarship Online. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master of Liberal Studies Theses by an authorized administrator of Rollins Scholarship Online. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Unbought Grace of Life: Chivalry in Western Literature A Project Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Liberal Studies by Richard N. Boggs May, 2012 Mentor: Dr. Thomas Cook Reader: Dr. Gail Sinclair Rollins College Hamilton Holt School Master of Liberal Studies Program Winter Park, Florida The Unbought Grace of Life: Chivalry in Western Literature By Richard N. Boggs May, 2012 Project Approved: ________________________________________ Mentor ________________________________________ Reader ________________________________________ Director, Master of Liberal Studies Program ________________________________________ Dean, Hamilton Holt School Rollins College Dedicated to my wife Elizabeth for her love, her patience and her unceasing support. CONTENTS I. Introduction 1 II. Greek Pre-Chivalry 5 III. Roman Pre-Chivalry 11 IV. The Rise of Christian Chivalry 18 V. The Age of Chivalry 26 VI. -

Downloaded from Brill.Com09/28/2021 09:41:18AM Via Free Access 102 M

Asian Medicine 7 (2012) 101–127 brill.com/asme Palpable Access to the Divine: Daoist Medieval Massage, Visualisation and Internal Sensation1 Michael Stanley-Baker Abstract This paper examines convergent discourses of cure, health and transcendence in fourth century Daoist scriptures. The therapeutic massages, inner awareness and visualisation practices described here are from a collection of revelations which became the founding documents for Shangqing (Upper Clarity) Daoism, one of the most influential sects of its time. Although formal theories organised these practices so that salvation superseded curing, in practice they were used together. This blending was achieved through a series of textual features and synæsthesic practices intended to address existential and bodily crises simultaneously. This paper shows how therapeutic inter- ests were fundamental to soteriology, and how salvation informed therapy, thus drawing atten- tion to the entanglements of religion and medicine in early medieval China. Keywords Massage, synæsthesia, visualisation, Daoism, body gods, soteriology The primary sources for this paper are the scriptures of the Shangqing 上清 (Upper Clarity), an early Daoist school which rose to prominence as the fam- ily religion of the imperial family. The soteriological goal was to join an elite class of divine being in the Shangqing heaven, the Perfected (zhen 真), who were superior to Transcendents (xianren 仙). Their teachings emerged at a watershed point in the development of Daoism, the indigenous religion of 1 I am grateful for the insightful criticisms and comments on draughts of this paper from Robert Campany, Jennifer Cash, Charles Chase, Terry Kleeman, Vivienne Lo, Johnathan Pettit, Pierce Salguero, and Nathan Sivin. -

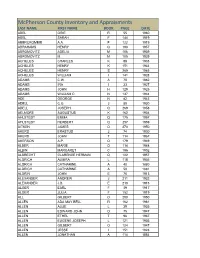

Mcpherson County Inventory and Appraisments LAST NAME FIRST NAME BOOK PAGE DATE ABEL ORIE R 55 1960 ABEL SARAH F 144 1919 ABERCROMBIE A.A

McPherson County Inventory and Appraisments LAST NAME FIRST NAME BOOK PAGE DATE ABEL ORIE R 55 1960 ABEL SARAH F 144 1919 ABERCROMBIE A.A. F 122 1919 ABRAHAMS HENRY Q 193 1957 ABROMOVITZ ADELIA M 106 1939 ABROMOVITZ M. M 105 1939 ACHILLES CHARLES K 88 1933 ACHILLES HENRY K 151 1934 ACHILLES HENRY S 289 1965 ACHILLES WILLIAM I 141 1928 ADAMS C.W. A 70 1882 ADAMS IRA I 33 1927 ADAMS JOHN H 129 1925 ADAMS WILLIAM C. N 147 1944 ADE GEORGE N 82 1943 ADELL C.G. J 80 1930 ADELL JOSEPH Q 269 1958 AELMORE AUGUSTUS K 162 1934 AHLSTEDT EMMA Q 175 1957 AHLSTEDT HERBERT Q 297 1959 AITKEN JAMES O 270 1950 AKERS ERASTUS J 74 1930 AKERS JOHN T 114 1967 AKERSON A.P. O 179 1949 ALBER MARIE O 114 1948 ALBIN MARGARET C 196 1902 ALBRECHT CLARENCE HERMAN Q 122 1957 ALDRICH ALMIRA L 118 1936 ALDRICH CATHARINE A 40 1880 ALDRICH CATHARINE A 50 1881 ALDRIN JOHN E 76 1913 ALEXANDER ANDREW J 211 1932 ALEXANDER J.B. E 210 1915 ALGER EARL F 39 1917 ALGER JULIA F 152 1919 ALL GILBERT O 290 1950 ALLEN ADA MAY BELL R 162 1961 ALLEN ALLIE L 39 1935 ALLEN EDWARD JOHN O 75 1947 ALLEN ETHEL T 96 1967 ALLEN EUGENE JOSEPH L 121 1936 ALLEN GILBERT O 124 1947 ALLEN JESSE I 151 1928 ALLEN JONATHAN A 114 1884 LAST NAME FIRST NAME BOOK PAGE DATE ALLEN LURA ELLEN Q 267 1958 ALLEN MARTHA C 174 1902 ALLEN NORMAN A 7 1878 ALLEN O.D. -

Carolingian Uncial: a Context for the Lothar Psalter

CAROLINGIAN UNCIAL: A CONTEXT FOR THE LOTHAR PSALTER ROSAMOND McKITTERICK IN his famous identification and dating ofthe Morgan Golden Gospels published in the Festschrift for Belle da Costa Greene, E. A. Lowe was quite explicit in his categorizing of Carolingian uncial as the 'invention of a display artist'.^ He went on to define it as an artificial script beginning to be found in manuscripts of the ninth century and even of the late eighth century. These uncials were reserved for special display purposes, for headings, titles, colophons, opening lines and, exceptionally, as in the case ofthe Morgan Gospels Lowe was discussing, for an entire codex. Lowe acknowledged that uncial had been used in these ways before the end of the eighth century, but then it was * natural' not 'artificial' uncial. One of the problems I wish to address is the degree to which Frankish uncial in the late eighth and the ninth centuries is indeed 'artificial' rather than 'natural'. Can it be regarded as a deliberate recreation of a script type, or is it a refinement and elevation in status of an existing book script? Secondly, to what degree is a particular script type used for a particular text type in the early Middle Ages? The third problem, related at least to the first, if not to the second, is whether Frankish uncial, be it natural or artificial, is sufficiently distinctive when used by a particular scriptorium to enable us to locate a manuscript or fragment to one atelier rather than another. This problem needs, of course, to be set within the context of later Carolingian book production, the notions of 'house' style as opposed to 'regional' style and the criteria for locating manuscript production to particular scriptoria in the Frankish kingdoms under the Carolingians that I have discussed elsewhere." It is also of particular importance when considering the Hofschule atehers ofthe mid-ninth century associated with the Emperor Lothar and with King Charles the Bald. -

Great Expectations on Screen

UNIVERSIDAD AUTÓNOMA DE MADRID FACULTAD DE FILOSOFÍA Y LETRAS DEPARTAMENTO DE HISTORIA Y TEORÍA DEL ARTE TESIS DOCTORAL GREAT EXPECTATIONS ON SCREEN A Critical Study of Film Adaptation Violeta Martínez-Alcañiz Directoras de la Tesis Doctoral: Prof. Dra. Valeria Camporesi y Prof. Dra. Julia Salmerón Madrid, 2018 UNIVERSIDAD AUTÓNOMA DE MADRID FACULTAD DE FILOSOFÍA Y LETRAS DEPARTAMENTO DE HISTORIA Y TEORÍA DEL ARTE TESIS DOCTORAL GREAT EXPECTATIONS ON SCREEN A Critical Study of Film Adaptation Tesis presentada por Violeta Martínez-Alcañiz Licenciada en Periodismo y en Comunicación Audiovisual para la obtención del grado de Doctor Directoras de la Tesis Doctoral: Prof. Dra. Valeria Camporesi y Prof. Dra. Julia Salmerón Madrid, 2018 “It was the best of times, it was the worst of times, it was the age of wisdom, it was the age of foolishness, it was the epoch of belief, it was the epoch of incredulity, it was the season of light, it was the season of darkness, it was the spring of hope, it was the winter of despair” (Charles Dickens, A Tale of Two Cities) “Now why should the cinema follow the forms of theater and painting rather than the methodology of language, which allows wholly new concepts of ideas to arise from the combination of two concrete denotations of two concrete objects?” (Sergei Eisenstein, “A dialectic approach to film form”) “An honest adaptation is a betrayal” (Carlo Rim) Table of contents ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 13 CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION 15 CHAPTER 2. LITERATURE REVIEW 21 Early expressions: between hostility and passion 22 Towards a theory on film adaptation 24 Story and discourse: semiotics and structuralism 25 New perspectives 30 CHAPTER 3. -

Planning a School Tour

Planning a school tour Image courtesy of: B. Han. Used with permission. CHI_Y05-06Band_U7_SS_PlanTour Gāo míng, zhè shì shěn me dì fang? Tā shì shéi ? 高明,这是 什么地方?他是谁? Gaoming, what is this place? Who is he? Ó ! Zhè shì wǒ men xué xiào de chuáng dá shì 哦! 这是 我们 学校 的 传达室。 Tā shì chuáng dá shì de lǐ yéye lǐ yéye zǎo 他是 传达室 的李爷爷。 “李爷爷早!” Oh! This is our school’s janitor’s room. He is janitor’s room’s Grandpa Li. “Good morning Grandpa Li) CHI_Y05-06Band_U7_SS_PlanTour Overseas exchange students 海外交换生 It was so cool to go on a school exchange to China! It’s also pretty awesome to have visitors from overseas come to my school. My school has some great features that I would love to show to an exchange student. CHI_Y05-06Band_U7_SS_PlanTour Let’s look at how Gao Ming showcased features of his school when I went there on exchange. What interesting aspects of his school does Gao Ming explain to me? CHI_Y05-06Band_U7_SS_PlanTour xué xiào dì tú School map - 学校 地图 I took Wilson to see the playground, classroom and cafeteria. Can you remember how I said the names of these places in Chinese? CHI_Y05-06Band_U7_SS_PlanTour CHI_Y05-06Band_U7_SS_PlanTour New word Jiào xué lóu 教学楼 – Teaching building CHI_Y05-06Band_U7_SS_PlanTour New word Shí táng 食堂 - Canteen CHI_Y05-06Band_U7_SS_PlanTour New word Huā pǔ 花圃 – flower bed CHI_Y05-06Band_U7_SS_PlanTour New word Tú shū guǎn 图书馆 - Library CHI_Y05-06Band_U7_SS_PlanTour New word Dú shū láng 读书廊- Reading corridor CHI_Y05-06Band_U7_SS_PlanTour New word Yī wù shì 医务室 – Medical room CHI_Y05-06Band_U7_SS_PlanTour New word Pīng pang qiú tái 乒乓球台-Table tennis table CHI_Y05-06Band_U7_SS_PlanTour New word Cāo cháng 操场 - Oval CHI_Y05-06Band_U7_SS_PlanTour New word Jiǎ shān shuǐ chí 假山水池-Artificial mountain and fountain. -

Charles Dickens Unit Study

Charles Dickens Unit Study Subjects: Reading, History, Writing, Math, Following Directions, Geography ©2019 Randi Smith www.peanutbutterfishlessons.com Teacher Instructions Thank you for downloading our Charles Dickens Unit Study! It was created to be used with the books: Magic Tree House: A Ghost Tale for Christmas Time and Who Was Charles Dickens?. You may incorporate other books about Charles Dickens, as well. Here is what is included in the study: Pages 3-10: Facts about Charles Dickens Notetaking Sheets: Use with Who Was…? Contains answer key. Pages 11-12: Facts about Charles Dickens Notetaking Sheets Short Version: Use with MTH. Contains answer key. Pages 13-16: Timeline of Charles Dickens’ Life: Students may write on timeline or cut and glue events provided. Page 17: Writing Prompt: Diary Entry of one of Dickens’ characters. Page 18: Scrambled Words Page 19: Compare and Contrast: Two of Dickens’ characters Pages 20-21: British Money Activity Page 22: Answer Key for Scrambled Words and Money Activity Pages 23-24: Following Directions in London with map. Also refer to our post: Charles Dickens FREE Unit Study for: 1. A list of some of his popular books and movies that are appropriate for children. 2. Videos to learn more about Charles Dickens 3. Links to other resources such as a Virtual Tour of the Charles Dickens Museum and A Christmas Carol FREE Unit Study. You May Also Be © Interested In: 2019 Credits www.peanutbutterfishlessons.com Smith Randi Frames by: Map Clip Art by: Facts about Charles Dickens Birth (date and place): _____________________________ -

Masculinity and Chivalry: the Tenuous Relationship of the Sacred and Secular in Medieval Arthurian Literature

MASCULINITY AND CHIVALRY: THE TENUOUS RELATIONSHIP OF THE SACRED AND SECULAR IN MEDIEVAL ARTHURIAN LITERATURE by KACI MCCOURT DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at The University of Texas at Arlington August, 2018 Arlington, Texas Supervising Committee: Kevin Gustafson, Supervising Professor Jacqueline Fay James Warren i ABSTRACT Masculinity and Chivalry: The Tenuous Relationship of the Sacred and Secular in Medieval Arthurian Literature Kaci McCourt, Ph.D. The University of Texas at Arlington, 2018 Supervising Professors: Kevin Gustafson, Jacqueline Fay, and James Warren Concepts of masculinity and chivalry in the medieval period were socially constructed, within both the sacred and the secular realms. The different meanings of these concepts were not always easily compatible, causing tensions within the literature that attempted to portray them. The Arthurian world became a place that these concepts, and the issues that could arise when attempting to act upon them, could be explored. In this dissertation, I explore these concepts specifically through the characters of Lancelot, Galahad, and Gawain. Representative of earthly chivalry and heavenly chivalry, respectively, Lancelot and Galahad are juxtaposed in the ways in which they perform masculinity and chivalry within the Arthurian world. Chrétien introduces Lancelot to the Arthurian narrative, creating the illicit relationship between him and Guinevere which tests both his masculinity and chivalry. The Lancelot- Grail Cycle takes Lancelot’s story and expands upon it, securely situating Lancelot as the best secular knight. This Cycle also introduces Galahad as the best sacred knight, acting as redeemer for his father. Gawain, in Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, exemplifies both the earthly and heavenly aspects of chivalry, showing the fraught relationship between the two, resulting in the emasculating of Gawain.