Introduction to Enjoy This Route, It Is Important to Approach It with the Right Expectations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Guide to Services Links and Resources for Health and Wellbeing

Guide to Services Links and Resources for Health and Wellbeing 2! ! ! ! ! Health!is!a!state!of! complete!physical,! mental!and!social! wellbeing!and!not! merely!the!absence! of!disease!or! infirmity! ! ! ! (World'Health'Organisation)' ! ! ! ! 3! Guide to Services Links and Resources For Health & Wellbeing Contents ! Introduction - Keeping Well 4 - 7 Emergency and Crisis Contacts 8 - 19 Who’s Who in the Community Mental Health Service 20 - 28 'Self Help Resources and Websites 29 - 42 Local Services and Agencies 43 - 68 List of Local Directories 69 - 73 Information on Local Groups and Activities 74 - 86 Index 87 - 94 Survey This is for You - Relaxation CD 4! 1. Eat a balanced diet and drink sensibly: Improving your diet can protect against feelings of anxiety and depression. 2. Maintain friendships: Just listening and talking to friends who are feeling down can make a huge difference. So make sure your devote time to maintaining your friendships both for their sake and your own. 3. Maintain close relationships: Close relationships affect how we feel - so nurture them and if there is a problem within a relationship, try and resolve it. 4. Take exercise: The effects of exercise on mood are immediate. Whether it is a workout in the gym or a simple walk or bike ride, it can be uplifting. Exercise can also be great fun socially. 5. Sleep: Sleep has both physical and mental benefits. Physically it is the time when the body can renew its energy store but sleep also helps us to rebuild our mental energy. 6. Laugh: A good laugh does wonders for the mind and soul. -

Battrum's Guide and Directory to Helensburgh and Neighbourhood

ii t^^ =»». fl,\l)\ National Library of Scotland ^6000261860' Digitized by tine Internet Arciiive in 2010 with funding from National Library of Scotland http://www.archive.org/details/battrumsguidedir1875batt u : MACNEUR & BRYDEN'S (31.-A.TE ""w. :b.aji}t:rtji^'&] GUIDE AND DIRECTORY TO HELENSBURGH AND NEIGHBOURHOOD, SEVENTH EDITIOK. ;^<A0MSjdi^ HELENSBUEGH MACNEUE & BUT & 52 East Princes Street, aad 19 West Clyde Street, 1875. 7. PREFACE. In issning the seventh edition of the Helensburgh Direc- tory, the publishers, remembering the kind apprecia- tion it received when published by the late Mr Battrum, trust that it will meet with a similar reception. Although imperfect in many respects, considerabie care has been expended in its compiling. It is now larger than anj^ previous issue, and the publishers doubt not it will be found useful as a book of reference in this daily increasing district. The map this year has been improved, showing the new feus, houses, and streets that have been made ; and, altogether, every effort has been made to render tbe Directory worthy of the town and neighbourhood. September' 1875. NAMES OF THE NEW POLICE COMMISSIONERS, Steveu, Mag. Wilhaiii Bryson. Thomas Chief j J. W. M'Culloch, Jun. Mag. John Crauib. John Stuart, Jun. Mag. Donald Murray. Einlay Campbell. John Dingwall, Alexander Breingan. B. S. MFarlane. Andrew Provan. Martin M' Kay. Towii-CJerk—Geo, Maclachlan. Treasurer—K. D, Orr. Macneur & Bkyden (successors to the late W. Battrum), House Factors and Accountants. House Register published as formerly. CONTENTS OF GUIDE. HELENSBURGH— page ITS ORIGIN, ..,.,..., 9 OLD RECORDS, H PROVOSTS, 14 CHURCHES, 22 BANKS, 26 TOWN HALL, . -

North Berwick Town Centre Strategy

North Berwick Town Centre Strategy 2018 Supplementary Guidance to the East Lothian Local Development Plan 2018 1 NORTH BERWICK TOWN CENTRE STRATEGY 1.0 Purpose of the North Berwick Town Centre Strategy 1.1 The North Berwick Town Centre Strategy forms a part of the adopted East Lothian Local Plan 2018 (LDP). It is supplementary guidance focusing on the changes that the Local Development Plan is planning to the town of North Berwick and the implications of that change for the town centre. The LDP introduces new planning policies adopting the town centre first principle and has detailed planning polices for town centres to guide development. 1.2 The strategy looks in more detail than the LDP into the town centre. A health check of the town centre is provided, its strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats are considered and its performance as a place with coordinated actions for improvement and regeneration. 1.3 In addition to the LDP and its supporting documents, the town centre strategy draws on the work done by the North Berwick Town Centre Charrette in 2015 and takes account of the Council’s emerging Local Transport Strategy as well as relevant parts of the North Berwick Coastal Area Partnership Area Plan. It is a material consideration in the determination of planning applications that affect the town centre. 2.0 Policy Context Local Development Plan Policy for Town Centres 2.1 The adopted East Lothian Local Development Plan 2018 (LDP) promotes the Town Centre First Principle which requires that uses that would attract significant footfall must consider locating to a town or local centre first and then, sequentially, to an edge of centre location, other commercial centre or out of centre location. -

WRITTEN STATEMENT Adopted March 2015

Argyll and Bute Local Development Plan WRITTEN STATEMENT Adopted March 2015 Plana-leasachaidh Ionadail Earra-ghàidheal is Bhòid If you would like this document in another language or format, or if you require the services of an interpreter, please contact us. Gaelic Jeżeli chcieliby Państwo otrzymać ten dokument w innym języku lub w innym formacie albo jeżeIi potrzebna jest pomoc tłumacza, to prosimy o kontakt z nami. Polish Hindi Urdu Punjabi Cantonese Mandarin Argyll and Bute Council, Kilmory, Lochgilphead PA31 8RT Telephone: 01546 604437 Fax: 01546 604349 1. Introduction 1.1 What is the Argyll and Bute Local Development Plan?………………………………………………….1 1.2 What does the Argyll and Bute Local Development Plan contain?...................................1 1.3 Supplementary Guidance……………………………………………………………………………………………..1 1.4 The wider policy context………………………………………………………………………………………………2 1.5 Implementation and delivery……………………………………………………………………………………….3 1.6 What if things change?.....................................................................................................4 1.7 Delivering sustainable economic growth—the central challenge………………………………….4 1.8 Vision and key objectives……………………………………………………………………………………………..5 1.9 Taking a sustainable approach to deliver our vision and key objectives………………………..7 Policy LDP STRAT 1— Sustainable Development…………………………………………………………..7 2. The Settlement and Spatial Strategy 2.1 Introduction………………………………………………………………………………………………………………...9 2.2 Oban, Lorn and the Isles…………………………………………………………………………………………….10 2.3 -

Watson's Directory for Paisley

% uOMMEBCIAL DIRECTORY M GE£TS: IVBBTISER 1375-76, ' Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2010 with funding from National Library of Scotland http://www.ar.chive.org/details/watsonsdirecto187576unse . WATSON'S DIRECTORY FOR PAISLEY, RENFREW, JOHNSTONE, ELDERSLIE, LINWOOD, QUARRELTON, THOKNHILL, BALACLAVA, AND INKERMAN, FOR THE YEAR 1875-76. PAISLEY: PRINTED AND PUBLISHED BY WM. B. WATSON, AT THE "PAISLEY HERALD" OFFICE, 10 HIGH STREET. I 8 7 5 COUNTING-HOUSE CALENDAR, From ] ST June, 1875, TILL 3 1{3T July, 1876 >-, > esi >. 35 c3 en 03 T3 oS o- -0 1875. 1876. c5 S3 o 53 3 3 53 3 'EH g A H H m DC 3 H 1 2 3 4 1 PS 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 M 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 1* 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 P 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 >-* 26 27 28 2930 31 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 fi 30 31 1 2 3 4| 5 6 1 2 3 8 P5 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 H 4 5 6 7 9 10 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 21 22 23 24 2627 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 O 35 28 29 30 ... ...... 25 26 27 28 29 30 1 1 2 1 PS 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 1 2 3 4 5 6 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 N 7 8 910 11 12 13 O 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 14 15 IS 19 20 H 3 16J17 o 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 21 22 232425 26 27 31 28 29 30 31 ll 2 3| 4 ] PS* 5 6 7 8 9 1011 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 12 13 14 15|l6 17 18 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 PS 19 20 21 2223 24 25 16 17 IS 19 20 21 22 <3 P, 26 27 28 29 30 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 m 30 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 li 2 3 4 OB 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 to 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 53 15 16 17 IS 19 20 21 12 13 14 1516 17 18 O < 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 29 30 31 26 27 28 29 30 31 1 2 3 1 2 3 4 5 PS h 4 .3 6 7 8 9 10 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 1-5 P P 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 >-5 IS 19 20 21 22 23124 P5 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 25 20 27 28 29 30 31 27 28 29 1 2 3 4 5 1 6 7 8 911011 12 P* 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 PS 13 14 15 16 17,18 19 «4 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 P 20 21 22 23 24,25 26 P 16 17 IS 19 20 21 22 >-a 27 28 29 30 ?,3 9,4 25 26 21 28 29 * 3031 1 I CONTENTS Page Paisley Street Guide .. -

Download Food & Drink Experiences Itinerary

Food and Drink Experiences TRAVEL TRADE Love East Lothian These itinerary ideas focus around great traditional Scottish hospitality, key experiences and meal stops so important to any trip. There is an abundance of coffee and cake havens, quirky venues, award winning bakers, fresh lobster and above all a pride in quality and in using ingredients locally from the fertile farm land and sea. The region boasts Michelin rated restaurants, a whisky distillery, Scotland’s oldest brewery, and several great artisan breweries too. Scotland has a history of gin making and one of the best is local from the NB Distillery. Four East Lothian restaurants celebrate Michelin rated status, The Creel, Dunbar; Osteria, North Berwick; as well as The Bonnie Badger and La Potiniere both in Gullane, recognising East Lothian among the top quality food and drink destinations in Scotland. Group options are well catered for in the region with a variety of welcoming venues from The Marine Hotel in North Berwick to Dunbar Garden Centre to The Prestoungrange Gothenburg pub and brewery in Prestonpans and many other pubs and inns in our towns and villages. visiteastlothian.org TRAVEL TRADE East Lothian Larder - making and tasting Sample some of Scotland’s East Lothian is proudly Scotland’s Markets, Farm Shops Sample our fish and seafood Whisky, Distilleries very best drinks at distilleries Food and Drink County. With a and Delis Our coastal towns all serve fish and and breweries. Glimpse their collection of producers who are chips, and they always taste best by importance in Scotland’s passionate about their products Markets and local farm stores the sea. -

20200917 H&L Area Committee Cardross

ARGYLL AND BUTE COUNCIL Helensburgh and Lomond Area Committee DEVELOPMENT AND ECONOMIC 17 September 2020 GROWTH Helensburgh, Cardross and Dumbarton Cyclepath Update 1.0 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1.1. This report updates Members of the progress made since reporting back to the Helensburgh and Lomond Area Committee on 19 March 2020 in relation to the delivery of Argyll and Bute Council’s long-standing commitment to the provision of a dedicated, high quality walking and cycle route linking Helensburgh, Cardross and Dumbarton. 1.2. Roads and Infrastructure Services commenced construction of the section of the route linking Cardross Station to the Geilston Burn in March 2020. Work was interrupted by Covid-19 from the 23 March and recommenced on 03 August. The revised construction programme indicates that the new bridge should be installed in September, with all work completed by end-October. 1.3. SUSTRANS confirmed on 31 July 2020 that they will provide funding in 2020/21 for developed and technical design development for the new preferred route for phase 1 (Helensburgh to Cardross) and for phase 2 (Cardross to Dumbarton). ARGYLL AND BUTE COUNCIL Helensburgh and Lomond Area Committee DEVELOPMENT AND ECONOMIC 17 September 2020 GROWTH Helensburgh, Cardross and Dumbarton Cyclepath Update 2.0 INTRODUCTION 2.1. This report updates Members of the progress made since the Helensburgh and Lomond Area Committee on 19 March 2020 in relation to the delivery of Argyll and Bute Council’s long-standing commitment to the provision of a dedicated, high quality walking and cycle route linking Helensburgh, Cardross and Dumbarton. 2.2. -

GRAVEYARD MONUMENTS in EAST LOTHIAN 213 T Setona 4

GRAVEYARD MONUMENT EASN SI T LOTHIAN by ANGUS GRAHAM, M.A., F.S.A., F.S.A.SCOT. INTRODUCTORY THE purpos thif eo s pape amplifo t s ri informatioe yth graveyare th n no d monuments of East Lothian that has been published by the Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Scotland.1 The Commissioners made their survey as long ago as 1913, and at that time their policy was to describe all pre-Reformation tombstones but, of the later material, to include only such monuments as bore heraldic device possesser so d some very notable artisti historicar co l interest thein I . r recent Inventories, however, they have included all graveyard monuments which are earlier in date than 1707, and the same principle has accordingly been followed here wit additioe latey hth an r f eighteenth-centurno y material which called par- ticularly for record, as well as some monuments inside churches when these exempli- fied types whic ordinarile har witt graveyardsyn hme i insignie Th . incorporatef ao d trades othed an , r emblems relate deceasea o dt d person's calling treatee ar , d separ- n appendixa atel n i y ; this material extends inte nineteentth o h centurye Th . description individuaf o s l monuments, whic takee har n paris parisy hb alphan hi - betical order precedee ar , reviea generae y th b df w o l resultsurveye th f so , with observations on some points of interest. To avoid typographical difficulties, all inscriptions are reproduced in capital letters irrespectiv nature scripe th th f whicf n eo i eto h the actualle yar y cut. -

The Inventory of Historic Battlefields – Battle of Prestonpans Designation

The Inventory of Historic Battlefields – Battle of Prestonpans The Inventory of Historic Battlefields is a list of nationally important battlefields in Scotland. A battlefield is of national importance if it makes a contribution to the understanding of the archaeology and history of the nation as a whole, or has the potential to do so, or holds a particularly significant place in the national consciousness. For a battlefield to be included in the Inventory, it must be considered to be of national importance either for its association with key historical events or figures; or for the physical remains and/or archaeological potential it contains; or for its landscape context. In addition, it must be possible to define the site on a modern map with a reasonable degree of accuracy. The aim of the Inventory is to raise awareness of the significance of these nationally important battlefield sites and to assist in their protection and management for the future. Inventory battlefields are a material consideration in the planning process. The Inventory is also a major resource for enhancing the understanding, appreciation and enjoyment of historic battlefields, for promoting education and stimulating further research, and for developing their potential as attractions for visitors. Designation Record and Full Report Contents Name - Context Alternative Name(s) Battlefield Landscape Date of Battle - Location Local Authority - Terrain NGR Centred - Condition Date of Addition to Inventory Archaeological and Physical Date of Last Update Remains and Potential -

East Lothian Council LIST of APPLICATIONS DECIDED by THE

East Lothian Council LIST OF APPLICATIONS DECIDED BY THE PLANNING AUTHORITY FOR PERIOD ENDING 24th July 2020 Part 1 App No 19/00995/PM Officer: Mr David Taylor Tel: 0162082 7430 Applicant Mactaggart And Mickel Homes Ltd Applicant’s Address 1 Atlantic Quay 1 Robertson Street Glasgow G2 8JB Agent Fouin+Bell Architects Agent’s Address 1 John's Place Edinburgh EH6 7EL Proposal Changes to plot numbers, house types, ground levels, repositioning of houses, erection of an additional 4 houses and associated works as changes to the scheme of development the subject of planning permission 13/00519/PM Location Letham Haddington East Lothian Date Decided 23rd July 2020 Decision Granted Permission Council Ward Haddington And Lammermuir Community Council Haddington Area Community Council App No 19/01265/P Officer: James Allan Tel: 0162082 7788 Applicant Dr Simon Bagley Applicant’s Address 28 The Maltings Haddington East Lothian EH41 4EF Agent Lochinvar Agent’s Address Per Mark MacKenzie 25 Fisherrow Industrial Estate Musselburgh EH21 6RU Proposal Extension to house Location 28 The Maltings Haddington East Lothian EH41 4EF Date Decided 21st July 2020 Decision Granted Permission Council Ward Haddington And Lammermuir Community Council Haddington Area Community Council App No 20/00330/P Officer: Sinead Wanless Tel: 0162082 7865 Applicant Mr Sean Corrigan Applicant’s Address 39 North Grange Avenue Prestonpans EH32 9NH Agent Irvine Design Services Agent’s Address Per Ross Irvine 16 West Loan Prestonpans Scotland EH32 9NT Proposal Extension to house Location -

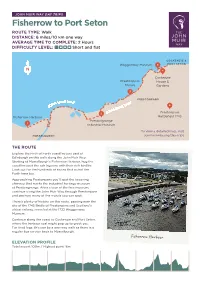

Fisherrow to Port Seton ROUTE TYPE: Walk DISTANCE: 6 Miles/10 Km One Way AVERAGE TIME to COMPLETE: 2 Hours DIFFICULTY LEVEL: Short and Flat

JOHN MUIR WAY DAY TRIPS Fisherrow to Port Seton ROUTE TYPE: Walk DISTANCE: 6 miles/10 km one way AVERAGE TIME TO COMPLETE: 2 Hours DIFFICULTY LEVEL: Short and flat COCKENZIE & Waggonway Museum 5 PORT SETON LONGNIDDRY 4 Cockenzie Prestonpans House & Murals Gardens 3 PRESTONPANS R W M U I AY Y H N A O W 6 J U IR N M OH 2 J Prestonpans Fisherrow Harbour Battlefield 1745 Prestongrange 1 Industrial Museum To view a detailed map, visit MUSSELBURGH joinmuirway.org/day-trips THE ROUTE Explore the Firth of Forth coastline just east of Edinburgh on this walk along the John Muir Way. Starting at Musselburgh’s Fisherrow Harbour, hug the coastline past the ash lagoons with their rich birdlife. Look out for the hundreds of swans that patrol the Forth here too. Approaching Prestonpans you’ll spot the towering chimney that marks the industrial heritage museum at Prestongrange. After a tour of the free museum, continue along the John Muir Way through Prestonpans and see how many of the murals you can spot. There’s plenty of history on this route, passing near the site of the 1745 Battle of Prestonpans and Scotland’s oldest railway, revealed at the 1722 Waggonway Museum. Continue along the coast to Cockenzie and Port Seton, where the harbour seal might pop up to greet you. For tired legs, this can be a one-way walk as there is a regular bus service back to Musselburgh. Fisherrow Harbour ELEVATION PROFILE Total ascent 100m / Highest point 16m JOHN MUIR WAY DAY TRIPS Fisherrow to Port Seton PLACES OF INTEREST 1 FISHERROW HARBOUR Just west of Musselburgh this harbour, built from 1850, is still used by pleasure and fishing boats. -

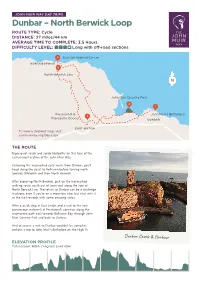

North Berwick Loop ROUTE TYPE: Cycle DISTANCE: 27 Miles/44 Km AVERAGE TIME to COMPLETE: 3.5 Hours DIFFICULTY LEVEL: Long with Off-Road Sections

JOHN MUIR WAY DAY TRIPS Dunbar – North Berwick Loop ROUTE TYPE: Cycle DISTANCE: 27 miles/44 km AVERAGE TIME TO COMPLETE: 3.5 Hours DIFFICULTY LEVEL: Long with off-road sections 4 Scottish Seabird Centre NORTH BERWICK 5 North Berwick Law John Muir Country Park 2 1 Prestonmill & John Muir’s Birthplace 3 Phantassie Doocot DUNBAR EAST LINTON To view a detailed map, visit joinmuirway.org/day-trips THE ROUTE Enjoy quiet roads and sandy footpaths on this tour of the easternmost section of the John Muir Way. Following the waymarked cycle route from Dunbar, you’ll head along the coast to Belhaven before turning north towards Whitekirk and then North Berwick. After exploring North Berwick, pick up the waymarked walking route south out of town and along the foot of North Berwick Law. The return to Dunbar can be a challenge in places, even if you’re on a mountain bike, but stick with it as the trail rewards with some amazing vistas. After a quick stop in East Linton and a visit to the very picturesque watermill at Prestonmill, continue along the waymarked path east towards Belhaven Bay, through John Muir Country Park and back to Dunbar. And of course a visit to Dunbar wouldn’t be complete without a trip to John Muir’s Birthplace on the High St. Dunbar Castle & Harbour ELEVATION PROFILE Total ascent 369m / Highest point 69m JOHN MUIR WAY DAY TRIPS Dunbar - North Berwick Loop PLACES OF INTEREST 1 JOHN MUIR’S BIRTHPLACE Pioneering conservationist, writer, explorer, botanist, geologist and inventor. Discover the many sides to John Muir in this museum located in the house where he grew up.