Steven Jones

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DESIGN-DRIVEN APPROACHES TOWARD MORE EXPRESSIVE STORYGAMES a Dissertation Submitted in Partial Satisfaction of the Requirements for the Degree Of

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA SANTA CRUZ CHANGEFUL TALES: DESIGN-DRIVEN APPROACHES TOWARD MORE EXPRESSIVE STORYGAMES A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in COMPUTER SCIENCE by Aaron A. Reed June 2017 The Dissertation of Aaron A. Reed is approved: Noah Wardrip-Fruin, Chair Michael Mateas Michael Chemers Dean Tyrus Miller Vice Provost and Dean of Graduate Studies Copyright c by Aaron A. Reed 2017 Table of Contents List of Figures viii List of Tables xii Abstract xiii Acknowledgments xv Introduction 1 1 Framework 15 1.1 Vocabulary . 15 1.1.1 Foundational terms . 15 1.1.2 Storygames . 18 1.1.2.1 Adventure as prototypical storygame . 19 1.1.2.2 What Isn't a Storygame? . 21 1.1.3 Expressive Input . 24 1.1.4 Why Fiction? . 27 1.2 A Framework for Storygame Discussion . 30 1.2.1 The Slipperiness of Genre . 30 1.2.2 Inputs, Events, and Actions . 31 1.2.3 Mechanics and Dynamics . 32 1.2.4 Operational Logics . 33 1.2.5 Narrative Mechanics . 34 1.2.6 Narrative Logics . 36 1.2.7 The Choice Graph: A Standard Narrative Logic . 38 2 The Adventure Game: An Existing Storygame Mode 44 2.1 Definition . 46 2.2 Eureka Stories . 56 2.3 The Adventure Triangle and its Flaws . 60 2.3.1 Instability . 65 iii 2.4 Blue Lacuna ................................. 66 2.5 Three Design Solutions . 69 2.5.1 The Witness ............................. 70 2.5.2 Firewatch ............................... 78 2.5.3 Her Story ............................... 86 2.6 A Technological Fix? . -

Edutainment Case Study

What in the World Happened to Carmen Sandiego? The Edutainment Era: Debunking Myths and Sharing Lessons Learned Carly Shuler The Joan Ganz Cooney Center at Sesame Workshop Fall 2012 1 © The Joan Ganz Cooney Center 2012. All rights reserved. The mission of the Joan Ganz Cooney Center at Sesame Workshop is to harness digital media teChnologies to advanCe Children’s learning. The Center supports aCtion researCh, enCourages partnerships to ConneCt Child development experts and educators with interactive media and teChnology leaders, and mobilizes publiC and private investment in promising and proven new media teChnologies for Children. For more information, visit www.joanganzCooneyCenter.org. The Joan Ganz Cooney Center has a deep Commitment toward dissemination of useful and timely researCh. Working Closely with our Cooney Fellows, national advisors, media sCholars, and praCtitioners, the Center publishes industry, poliCy, and researCh briefs examining key issues in the field of digital media and learning. No part of this publiCation may be reproduCed or transmitted in any form or by any means, eleCtroniC or meChaniCal, inCluding photoCopy, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Joan Ganz Cooney Center at Sesame Workshop. For permission to reproduCe exCerpts from this report, please ContaCt: Attn: PubliCations Department, The Joan Ganz Cooney Center at Sesame Workshop One Lincoln Plaza New York, NY 10023 p: 212 595 3456 f: 212 875 7308 [email protected] Suggested Citation: Shuler, C. (2012). Where in the World is Carmen Sandiego? The Edutainment Era: Debunking Myths and Sharing Lessons Learned. New York: The Joan Ganz Cooney Center at Sesame Workshop. -

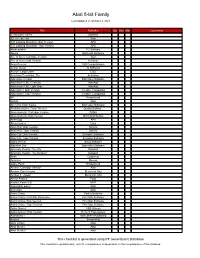

Atari 8-Bit Family

Atari 8-bit Family Last Updated on October 2, 2021 Title Publisher Qty Box Man Comments 221B Baker Street Datasoft 3D Tic-Tac-Toe Atari 747 Landing Simulator: Disk Version APX 747 Landing Simulator: Tape Version APX Abracadabra TG Software Abuse Softsmith Software Ace of Aces: Cartridge Version Atari Ace of Aces: Disk Version Accolade Acey-Deucey L&S Computerware Action Quest JV Software Action!: Large Label OSS Activision Decathlon, The Activision Adventure Creator Spinnaker Software Adventure II XE: Charcoal AtariAge Adventure II XE: Light Gray AtariAge Adventure!: Disk Version Creative Computing Adventure!: Tape Version Creative Computing AE Broderbund Airball Atari Alf in the Color Caves Spinnaker Software Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves Quality Software Alien Ambush: Cartridge Version DANA Alien Ambush: Disk Version Micro Distributors Alien Egg APX Alien Garden Epyx Alien Hell: Disk Version Syncro Alien Hell: Tape Version Syncro Alley Cat: Disk Version Synapse Software Alley Cat: Tape Version Synapse Software Alpha Shield Sirius Software Alphabet Zoo Spinnaker Software Alternate Reality: The City Datasoft Alternate Reality: The Dungeon Datasoft Ankh Datamost Anteater Romox Apple Panic Broderbund Archon: Cartridge Version Atari Archon: Disk Version Electronic Arts Archon II - Adept Electronic Arts Armor Assault Epyx Assault Force 3-D MPP Assembler Editor Atari Asteroids Atari Astro Chase Parker Brothers Astro Chase: First Star Rerelease First Star Software Astro Chase: Disk Version First Star Software Astro Chase: Tape Version First Star Software Astro-Grover CBS Games Astro-Grover: Disk Version Hi-Tech Expressions Astronomy I Main Street Publishing Asylum ScreenPlay Atari LOGO Atari Atari Music I Atari Atari Music II Atari This checklist is generated using RF Generation's Database This checklist is updated daily, and it's completeness is dependent on the completeness of the database. -

Finding Aid to the Brøderbund Software, Inc. Collection, 1979-2002

Brian Sutton-Smith Library and Archives of Play Brøderbund Software, Inc. Collection Finding Aid to the Brøderbund Software, Inc. Collection, 1979-2002 Summary Information Title: Brøderbund Software, Inc. collection Creator: Douglas Carlston and Brøderbund Software, Inc. (primary) ID: 114.892 Date: 1979-2002 (inclusive); 1980-1998 (bulk) Extent: 8.5 linear feet Language: The materials in this collection are in English, unless otherwise indicated. Abstract: The Brøderbund Software, Inc. collection is a compilation of Brøderbund business records and information on the Software Publishers Association (SPA). The majority of the materials are dated between 1980 and 1998. Repository: Brian Sutton-Smith Library and Archives of Play at The Strong One Manhattan Square Rochester, New York 14607 585.263.2700 [email protected] Administrative Information Conditions Governing Use: This collection is open for research use by staff of The Strong and by users of its library and archives. Though the donor has not transferred intellectual property rights (including, but not limited to any copyright, trademark, and associated rights therein) to The Strong, he has given permission for The Strong to make copies in all media for museum, educational, and research purposes. Custodial History: The Brøderbund Software, Inc. collection was donated to The Strong in January 2014 as a gift from Douglas Carlston. The papers were accessioned by The Strong under Object ID 114.892. The papers were received from Carlston in 5 boxes, along with a donation of Brøderbund software products and related corporate ephemera. Preferred citation for publication: Brøderbund Software, Inc. collection, Brian Sutton- Smith Library and Archives of Play at The Strong Processed by: Julia Novakovic, February 2014 Controlled Access Terms Personal Names • Carlston, Cathy • Carlston, Doug, 1947- • Carlston, Gary • Pelczarski, Mark • Wasch, Ken • Williams, Ken Corporate Names • Brøderbund • Brøderbund Software, Inc. -

The History of Educational Computer Games

Beyond Edutainment Exploring the Educational Potential of Computer Games By Simon Egenfeldt-nielsen Submitted to the IT-University of Copenhagen as partial fulfilment of the requirements for the PhD degree February, 2005 Candidate: Simon Egenfeldt-Nielsen Købmagergade 11A, 4. floor 1150 Copenhagen +45 40107969 [email protected] Supervisors: Anker Helms Jørgensen and Carsten Jessen Abstract Computer games have attracted much attention over the years, mostly attention of the less flattering kind. This has been true for computer games focused on entertainment, but also for what for years seemed a sure winner, edutainment. This dissertation aims to be a modest contribution to understanding educational use of computer games by building a framework that goes beyond edutainment. A framework that goes beyond the limitations of edutainment, not relying on a narrow perception of computer games in education. The first part of the dissertation outlines the background for building an inclusive and solid framework for educational use of computer games. Such a foundation includes a variety of quite different perspectives for example educational media and non-electronic games. It is concluded that educational use of computer games remains strongly influenced by educational media leading to the domination of edutainment. The second part takes up the challenges posed in part 1 looking to especially educational theory and computer games research to present alternatives. By drawing on previous research three generations of educational computer games are identified. The first generation is edutainment that perceives the use of computer games as a direct way to change behaviours through repeated action. The second generation puts the spotlight on the relation between computer game and player. -

Conference Booklet

30th Oct - 1st Nov CONFERENCE BOOKLET 1 2 3 INTRO REBOOT DEVELOP RED | 2019 y Always Outnumbered, Never Outgunned Warmest welcome to first ever Reboot Develop it! And we are here to stay. Our ambition through Red conference. Welcome to breathtaking Banff the next few years is to turn Reboot Develop National Park and welcome to iconic Fairmont Red not just in one the best and biggest annual Banff Springs. It all feels a bit like history repeating games industry and game developers conferences to me. When we were starting our European older in Canada and North America, but in the world! sister, Reboot Develop Blue conference, everybody We are committed to stay at this beautiful venue was full of doubts on why somebody would ever and in this incredible nature and astonishing choose a beautiful yet a bit remote place to host surroundings for the next few forthcoming years one of the biggest worldwide gatherings of the and make it THE annual key gathering spot of the international games industry. In the end, it turned international games industry. We will need all of into one of the biggest and highest-rated games your help and support on the way! industry conferences in the world. And here we are yet again at the beginning, in one of the most Thank you from the bottom of the heart for all beautiful and serene places on Earth, at one of the the support shown so far, and even more for the most unique and luxurious venues as well, and in forthcoming one! the company of some of the greatest minds that the games industry has to offer! _Damir Durovic -

Myst Windows Manual 2

INSTRUCTION MANUAL You have just stumbled upon a most intriguing A MESSAGE FROM CYAN book: a book titled Myst®. You have no idea where You are about to be drawn into an amazing alternative it came from, who wrote it, or how old it is. reality. The entire game was designed from the ground up to draw you in with little or no extraneous distractions on Reading through its pages provides you with only the screen to interfere with the feeling of being there. a superbly crafted description of an island world. Myst® is not linear, it’s not flat, it’s not shallow. This is But it’s just a book, isn’t it? the most depth, detail, and reality you’ve ever experienced in a game. As you reach the end of the book, you lay your hand on a page. Myst is real. And like real life, you don’t die every five minutes. In fact, you probably Suddenly your own world dissolves into blackness, replaced with the won’t die at all. There are no dead ends; you may hit a wall, but there is always a way island world the pages described. Now you’re here, wherever here is, with over or around. Pay attention to detail and collect information because those are the pieces of the puzzle that you’ll use to uncover the secrets of Myst. The puzzles you no option but to explore... encounter will be solved with logic and information – information garnered either from Myst or from life itself. The key to Myst is to lose yourself in this fantastic virtu- al exploration, and act and react as if you were really there. -

Amy Clary: "Digital Nature: Uru and the Representation of Wilderness in Computer Games"

Digital Nature: Uru and the Representation of Wilderness in Computer Games Amy Clary The desert is intense. The parched red earth bakes under the relentless glare of the afternoon sun. Thirsty-looking clumps of sage, too squat and sere to cast much shadow, dot the dry, cracked land. On the barbed wire fence is a sign, sunbleached and wind- scoured, that reads “No Trespassing” and “New Mexico.” A rusty Airstream trailer blends into the unforgiving landscape like the shell of a desert tortoise. Two oases of shade beckon: one under the awning of the vintage Airstream, another cast by a distant red rock butte. I head toward the butte, eager to explore its alluringly steep slopes and jagged profile. I climb up the slope and realize that it is not a butte at all but the entrance to a sort of canyon, a cleft, with a seductive assortment of shapes and shade inside it. I take anoth- er step and … the whole world dissolves into unintelligible poly- gons of color. All I see is chaos, and try as I might, I can’t get back to the desert. Such are the frustrations of playing Uru: Ages Beyond Myst (Cyan Worlds, 2003) on a computer that barely meets the game’s mini- mum system requirements. Reviewer Darryl Vassar writes, “Uru will make even the beefiest video card sweat at the highest detail settings…” (“Incomparable beauty” section: para. 4). I had hoped that by turning the game’s graphics settings down to the bare-bones level, my processor, video card, and memory would be sufficient to the task, but they were not. -

The Boom and Bust and Boom of Educational Games

The Boom and Bust and Boom of Educational Games The MIT Faculty has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters. Citation Klopfer, Eric, and Scot Osterweil. “The Boom and Bust and Boom of Educational Games.” Transactions on Edutainment IX (2013): 290– 296. As Published http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-37042-7_21 Publisher Springer-Verlag Version Author's final manuscript Citable link http://hdl.handle.net/1721.1/93079 Terms of Use Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike Detailed Terms http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/ The Boom and Bust and Boom of Educational Games Eric Klopfer and Scot Osterweil MIT Teacher Education Program and The Education Arcade The history of computer-based learning games has a story arc that rises dramatically, and then plummets steeply. In the early days of personal computers, creative minds drawn to the new medium explored a variety of approaches to learning games, ranging from behaviorist drill-and-practice exercises, to open- ended environments suitable for either exploration or construction. Early practitioners were inventing new forms, and even the fundamentally limited drill- and-practice games were infused with a measure of creative energy and humor. For users of these early products, each new title represented another interesting step into unknown territory. The CD ROM Era These products were first delivered on floppy disks and marketed alongside pure entertainment games in the few computer stores of the time. By the early 90’s the adoption of compact disk (CD) drives, and improved processing speeds led to a flowering of products with increasingly rich art, animation and more sophisticated computational possibilities. -

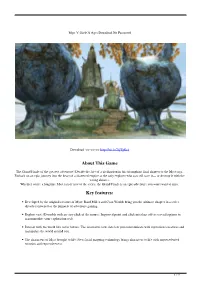

Myst V End of Ages Download No Password

Myst V: End Of Ages Download No Password Download ->>->>->> http://bit.ly/2QTgKcj About This Game The Grand Finale of the greatest adventure! Decide the fate of a civilization in this triumphant final chapter to the Myst saga. Embark on an epic journey into the heart of a shattered empire as the only explorer who can still save it— or destroy it with the wrong choices. Whether you’re a longtime Myst fan or new to the series, the Grand Finale is an epic adventure you won’t want to miss. Key features: Developed by the original creators of Myst: Rand Miller and Cyan Worlds bring you the ultimate chapter in a series already renowned as the pinnacle of adventure gaming. Explore vast 3D worlds with an easy click of the mouse: Improved point-and-click interface offers several options to accommodate your exploration style. Interact with the world like never before: The innovative new slate lets you communicate with mysterious creatures and manipulate the world around you. The characters of Myst brought to life: New facial mapping technology brings characters to life with unprecedented emotion and expressiveness. 1 / 11 Title: Myst V: End of Ages Genre: Adventure, Casual Developer: Cyan Worlds Publisher: Cyan Worlds Release Date: 19 Jul, 2005 7ad7b8b382 English,French,German,Italian,Japanese,Polish,Russian 2 / 11 3 / 11 4 / 11 5 / 11 myst v end of ages for mac. myst v end of ages wiki. myst v end of ages pc download. myst 5 end of ages torrent. myst v end of ages. myst.v.end.of.ages - skidrow. -

Guerrillas in the Myst

Guerrillas in the Myst In Myst, brothers Rand and Robyn Miller have given us the first CD-ROM smash hit. By Jon Carroll The doorman at Arthur Siegel's office building thought he was the most dedicated lawyer in San Francisco. Siegel would work long into the night; sometimes he would walk uncertainly out into the gray streets just before dawn, toting a heavy briefcase and squinting against the glare. But Siegel was not doing legal work in his ninth-floor office. He was playing Myst. "It was addictive," he says, "but I knew it had an end. I was pretty sure, anyway. Most of the time. The only problem was when I began clicking on things in real life. I'd see a manhole cover and think, 'Hmmm, that looks pretty interesting,' and my forefinger would start to twitch. And then I'd realize, 'No, it's real life. Real life is the thing that happens in between Myst.'" Myst is a phenomenon like no other in the world of CD-ROM. That's not a remarkable statement; CD-ROM is too new to have already had many phenomena. Mostly it's had complaints and dire predictions -- it's too slow, it's too expensive, it's too clunky. Junk has been hurled onto the market; every fast-buck artist with a pressing machine and access to fancy graphics has been throwing stuff against the wall and hoping some of it turns into money. As of the end of 1993, there were only about 3.5 million CD-ROM drives in private hands, according to InfoTech, a market research firm in Woodstock, Vermont. -

Obduction by Cyan, Inc

Obduction by Cyan, Inc. • Home • Updates 19 • Backers 15,407 • Comments 5,790 • Spokane, WA • Video Games Leave a comment (for backers only) Show 15 newer comments 1. Paul Melampy 1 minute ago Damn! That's 12K in the last 3 hours! 2. Mat 'Cubase' Van Rhoon 1 minute ago @Frank Ah, you spotted my nickname yes? Well done, and Indeed I am! I write film/game scores, and am also a sound designer. 3. Frank den Blaauwen 5 minutes ago @Mat: Interested in music writing/playing/producing? 4. Mat 'Cubase' Van Rhoon 8 minutes ago Greetings from the Tex Murphy crew! I am pretty darn confident you guys are not only going to make the funding goal, but will release a totally phenomenal game. I followed MYST ever since I borrowed a copy from my school library back when I was 9 years old... and never gave it back! Kudos too Rand and EVERYBODY at Cyan for keeping the adventure genre beating in our hearts! Oh and by the way, major props on a stellar KickStarter campaign! 5. Frank den Blaauwen 8 minutes ago I should type faster 6. Frank den Blaauwen 9 minutes ago @Allan: And the there was one... 7. Allan Børgesen 10 minutes ago 1 Strata Artist left 8. Tai'lahr 10 minutes ago @Jarrod: Okay, it looks like I'm going to have to wait awhile before RAWA's mom comes to the cavern, but what about you? Whatcha waiting on? Come have fun with us. Here's your "how to" - http://www.mystonline.com/forums/viewtopic.php… 9.