Border Archaeology, 2009)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Brycheiniog Vol 42:44036 Brycheiniog 2005 28/2/11 10:18 Page 1

68531_Brycheiniog_Vol_42:44036_Brycheiniog_2005 28/2/11 10:18 Page 1 BRYCHEINIOG Cyfnodolyn Cymdeithas Brycheiniog The Journal of the Brecknock Society CYFROL/VOLUME XLII 2011 Golygydd/Editor BRYNACH PARRI Cyhoeddwyr/Publishers CYMDEITHAS BRYCHEINIOG A CHYFEILLION YR AMGUEDDFA THE BRECKNOCK SOCIETY AND MUSEUM FRIENDS 68531_Brycheiniog_Vol_42:44036_Brycheiniog_2005 28/2/11 10:18 Page 2 CYMDEITHAS BRYCHEINIOG a CHYFEILLION YR AMGUEDDFA THE BRECKNOCK SOCIETY and MUSEUM FRIENDS SWYDDOGION/OFFICERS Llywydd/President Mr K. Jones Cadeirydd/Chairman Mr J. Gibbs Ysgrifennydd Anrhydeddus/Honorary Secretary Miss H. Gichard Aelodaeth/Membership Mrs S. Fawcett-Gandy Trysorydd/Treasurer Mr A. J. Bell Archwilydd/Auditor Mrs W. Camp Golygydd/Editor Mr Brynach Parri Golygydd Cynorthwyol/Assistant Editor Mr P. W. Jenkins Curadur Amgueddfa Brycheiniog/Curator of the Brecknock Museum Mr N. Blackamoor Pob Gohebiaeth: All Correspondence: Cymdeithas Brycheiniog, Brecknock Society, Amgueddfa Brycheiniog, Brecknock Museum, Rhodfa’r Capten, Captain’s Walk, Aberhonddu, Brecon, Powys LD3 7DS Powys LD3 7DS Ôl-rifynnau/Back numbers Mr Peter Jenkins Erthyglau a llyfrau am olygiaeth/Articles and books for review Mr Brynach Parri © Oni nodir fel arall, Cymdeithas Brycheiniog a Chyfeillion yr Amgueddfa piau hawlfraint yr erthyglau yn y rhifyn hwn © Except where otherwise noted, copyright of material published in this issue is vested in the Brecknock Society & Museum Friends 68531_Brycheiniog_Vol_42:44036_Brycheiniog_2005 28/2/11 10:18 Page 3 CYNNWYS/CONTENTS Swyddogion/Officers -

Pant Y Butler Llangoedmor, Cardigan Ceredigion

PANT Y BUTLER LLANGOEDMOR, CARDIGAN CEREDIGION TOPOGRAPHICAL AND GEOPHYSICAL SURVEY REPORT No 2008/118 Prepared by Dyfed Archaeological Trust For Cadw DYFED ARCHAEOLOGICAL TRUST RHIF YR ADRODDIAD / REPORT NO. 2008/111 RHIF Y PROSIECT / PROJECT RECORD NO.94536 Geophysical Survey PRN 93997 Topographical Survey PRN 93998 Rhagfyr 2008 December 2008 PANT Y BUTLER LLANGOEDMOR, CARDIGAN CEREDIGION TOPOGRAPHICAL AND GEOPHYSICAL SURVEY Gan / By PETE CRANE BA HONS MIFA AND HUBERT WILSON Paratowyd yr adroddiad yma at ddefnydd y cwsmer yn unig. Ni dderbynnir cyfrifoldeb gan Ymddiriedolaeth Archaeolegol Dyfed Cyf am ei ddefnyddio gan unrhyw berson na phersonau eraill a fydd yn ei ddarllen neu ddibynnu ar y gwybodaeth y mae’n ei gynnwys The report has been prepared for the specific use of the client. Dyfed Archaeological Trust Limited can accept no responsibility for its use by any other person or persons who may read it or rely on the information it contains. Ymddiriedolaeth Archaeolegol Dyfed Cyf Dyfed Archaeological Trust Limited Neuadd y Sir, Stryd Caerfyrddin, Llandeilo, Sir The Shire Hall, Carmarthen Street, Llandeilo, Gaerfyrddin SA19 6AF Carmarthenshire SA19 6AF Ffon: Ymholiadau Cyffredinol 01558 823121 Tel: General Enquiries 01558 823121 Adran Rheoli Treftadaeth 01558 823131 Heritage Management Section 01558 823131 Ffacs: 01558 823133 Fax: 01558 823133 Ebost: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Gwefan: www.archaeolegdyfed.org.uk Website: www. dyfedarchaeology .org.uk Cwmni cyfyngedig (1198990) ynghyd ag elusen gofrestredig (504616) yw’r Ymddiriedolaeth. The Trust is both a Limited Company (No. 1198990) and a Registered Charity (No. 504616) CADEIRYDD CHAIRMAN: C R MUSSON MBE B Arch FSA MIFA. -

Welsh Genealogy Pdf Free Download

WELSH GENEALOGY PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Bruce Durie | 288 pages | 01 Feb 2013 | The History Press Ltd | 9780752465999 | English | Stroud, United Kingdom Welsh Genealogy PDF Book Findmypast also has many other Welsh genealogy records including census returns, the Register, trade directories and newspapers. Judaism has quite a long history in Wales, with a Jewish community recorded in Swansea from around Arthfoddw ap Boddw Ceredigion — Approximately one-sixth of the population, some , people, profess no religious faith whatsoever. Wales Wiki Topics. Owen de la Pole — Brochfael ap Elisedd Powys — Cynan ap Hywel Gwynedd — Retrieved 9 May ". Settlers from Wales and later Patagonian Welsh arrived in Newfoundland in the early 19th century, and founded towns in Labrador 's coast region; in , the ship Albion left Cardigan for New Brunswick , carrying Welsh settlers to Canada; on board were 27 Cardigan families, many of whom were farmers. Media Category Templates WikiProject. Flag of Wales. The high cost of translation from English to Welsh has proved controversial. Maelgwn ap Rhys Deheubarth — Goronwy ap Tudur Hen d. A speaker's choice of language can vary according to the subject domain known in linguistics as code-switching. More Wales Genealogy Record Sources. Dafydd ap Gruffydd — By the 19th century, double names Hastings-Bowen were used to distinguish people of the same surname using a hyphenated mother's maiden name or a location. But if not, take heart because the excellent records kept by our English and Welsh forefathers means that record you need is just am 'r 'n gyfnesaf chornela around the next corner. This site contains a collection of stories, photographs and documents donated by the people of Wales. -

Dalton Visits the UK

ZULU VISITS UK by Bill Cainan Lidizwe Dalton Ngobese is currently employed as a tour guide at the Isandlwana Lodge in KwaZulu Natal. He is the great great grandson of Sihayo and the great grandson of Mehlokazulu. In June of 2010 he was able, due to a kind benefactor, to visit the UK for the first time. Dalton planned a five day itinerary, the main aim of which was to visit the SWB Museum at Brecon. Once the visit was confirmed the curator of the Museum, Martin Everett, rang me to ask if I would be willing to host Dalton while he was in UK. Having met Dalton a few times in KZN I was delighted to accept the offer. Dalton’s visit coincided with the UK’s Armed Forces Day which, in 2010, was being held in Cardiff with HRH Prince Charles, the Prince of Wales, taking the salute. The Prince was also scheduled to open “Firepower”, the museum of the Welsh Soldier, which was located within Cardiff Castle. A plan quickly took shape involving Dalton in full Zulu regalia and myself in a uniform of a Corporal of the 24th to be in attendance at the entrance to the Museum. Dalton was also keen to visit some of the more famous Welsh castles on his visit. The diary of his visit is as follows: Wednesday 23rd June: Dalton arrives at Cardiff airport having flown from Jo’burg via Schipol. There were a few problems with the UK’s Border Agency , but when Dalton produced the formal invite to the opening of “Firepower” in Cardiff (TO BE ATTENDED BY HRH THE PRINCE OF WALES), things seemed to get a bit easier! I then drove Dalton the 50 miles to Brecon and he was given a quick tour of the Museum by Martin Everett (the Curator) and Celia Green (the Customer Services Manager). -

Le Coastal Way

Le Coastal Way Une épopée à travers le Pays de Galles thewalesway.com visitsnowdonia.info visitpembrokeshire.com discoverceredigion.wales Où est le Pays de Galles? Prenez Le Wales Way! Comment s’y rendre? Le Wales Way est un voyage épique à travers trois routes distinctes: Le North On peut rejoindre le Pays de Galles par toutes les villes principales du Royaume-Uni, y compris Londres, Wales Way, Le Coastal Way et Le Cambrian Way, qui vous entraînent dans les Birmingham, Manchester et Liverpool. Le Pays de Galles possède son propre aéroport international, contrées des châteaux, au long de la côte et au coeur des montagnes. le Cardiff International Airport (CWL), qui est desservi par plus de 50 routes aériennes directes, reliant ainsi les plus grandes capitales d’Europe et offrant plus de 1000 connections pour les destinations du Le Coastal Way s’étend sur la longueur entière de la baie de Cardigan. C’est une odyssée de 180 monde entier. Le Pays de Galles est également facilement joignable par les aéroports de Bristol (BRS), miles/290km qui sillonne entre la mer azur d’un côté et les montagnes imposantes de l’autres. Birmingham (BHX), Manchester (MAN) et Liverpool (LPL). Nous avons décomposé le voyage en plusieurs parties pour que vous découvriez les différentes destinations touristiques du Pays de Galles: Snowdonia Mountains and Coast, le Ceredigion et A 2 heures de Londres en train le Pembrokeshire. Nous vous présentons chacune de ces destinations que vous pouvez visiter tout le long de l’année selon ces différentes catégories:Aventure, Patrimoine, Nature, Boire et Manger, Randonnée, et Golf. -

HISTORY of ABERYSTWYTH

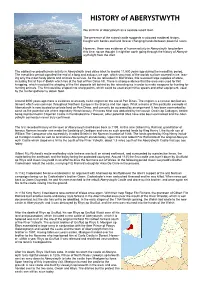

HISTORY of ABERYSTWYTH We all think of Aberystwyth as a seaside resort town. The presence of the ruined castle suggests a coloured medieval history, fraught with battles and land forever changing hands between powerful rulers. However, there was evidence of human activity in Aberystwyth long before this time, so we thought it might be worth going through the history of Aberyst- wyth right from the start. The earliest recorded human activity in Aberystwyth area dates back to around 11,500 years ago during the mesolithic period. The mesolithic period signalled the end of a long and arduous ice age, which saw most of the worlds surface covered in ice, leav- ing only the most hardy plants and animals to survive. As the ice retreaded in Mid Wales, this revealed large supplies of stone, including flint at Tan-Y-Bwlch which lies at the foot of Pen Dinas hill. There is strong evidence that the area was used for flint knapping, which involved the shaping of the flint deposits left behind by the retreating ice in order to make weapons for hunting for hunting animals. The flint could be shaped into sharp points, which could be used as primitive spears and other equipment, used by the hunter gatherer to obtain food. Around 3000 years ago there is evidence of an early Celtic ringfort on the site of Pen Dinas. The ringfort is a circular fortified set- tlement which was common throughout Northern Europe in the Bronze and Iron ages. What remains of this particular example at Aberystwyth is now located on private land on Pen Dinas, and can only be accessed by arrangement. -

The Status of the Marsh Fritillary in Wales: 2016

The Status of the Marsh Fritillary in Wales: 2016 A lean year… If you visited a Marsh Fritillary site during the 2016 flight season you were probably struck by just how few butterflies were flying, even when the weather was fine – not just Marsh Fritillaries, but other species too. This was the case even on sites which held good numbers of larval webs in the autumn of 2015. It was all rather puzzling. But just how badly did the Marsh Fritillary fare in 2016? Keep reading to find out… Introduction The conservation of the Marsh Fritillary, one of the most rapidly declining butterflies in Europe, hinges on knowing where our core populations are, how they are faring and making sure that sites are well managed for the butterfly. Where are they? – Population status surveys To maintain an up-to-date picture of where our Welsh Marsh Fritillary populations are (distribution) Butterfly Conservation Wales (BCW) co-ordinates a Wales-wide programme of visits in which every population gets at least one survey visit every five years. As well as confirming presence or absence, these visits can also highlight concerns, such as management issues, that need following up. How strong are they? – Surveillance programme To assess how strong our Marsh Fritillary populations are, and how this changes over time, the Wales Marsh Fritillary Surveillance Programme was established in 2012 by BCW in partnership with Natural Resources Wales (NRW). Annual larval web counts of key populations (21 currently) are undertaken and used to calculate both site-level and Wales-wide trends. 1 Population Status Surveys The rolling programme of five-yearly site visits continued in 2016. -

Endless Summer

This document is a snapshot of content from a discontinued BBC website, originally published between 2002-2011. It has been made available for archival & research purposes only. Please see the foot of this document for Archive Terms of Use. 20 April 2012 Accessibility help Text only BBC Homepage Wales Home Endless Summer more from this section Last updated: 17 July 2007 Aber Now Take a look at the slideshow of photographs from an Clubs and Societies exhibition - Endless Summer 1901-1906 - held at Ceredigion Food and Drink In Pictures Museum between 21 July and 1 September 2007. Captions Music are by the museum's curator, Michael Freeman. People BBC Local Sport and Leisure Mid Wales More old photos of Aberystwyth... Student Life Things to do What's on Your Say People & Places Nature & Outdoors Aber Then History Aber Connections Religion & Ethics A shop's century A stroll around the harbour Arts & Culture Aber Prom Music Ceredigion Museum TV & Radio Ghosts on the prom Great Storm of 1938 Local BBC Sites Holiday Memories News House Detective Sport Jackie 'The Monster' Jenkins King's Hall Memories Weather Martin's Memories Travel North Parade 1905-1926 Pendinas Neighbouring Sites Plas Tan y Bwlch North East Wales Prom Days North West Wales RAF at The Belle Vue South East Wales Salford Lads and Girls' club South West Wales Sea Stories The Dinner Scheme Related BBC Sites University photos Wales Ukraine's Unsung Hero Cymru Aberystwyth Beach WW2 stories What's in a name Canolbarth 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 related bbc.co.uk links Michael:"Ceredigion Museum has a number of photograph albums in its collection. -

Ceredigion Welsh District Council Elections Results 1973-1991

Ceredigion Welsh District Council Elections Results 1973-1991 Colin Rallings and Michael Thrasher The Elections Centre Plymouth University The information contained in this report has been obtained from a number of sources. Election results from the immediate post-reorganisation period were painstakingly collected by Alan Willis largely, although not exclusively, from local newspaper reports. From the mid- 1980s onwards the results have been obtained from each local authority by the Elections Centre. The data are stored in a database designed by Lawrence Ware and maintained by Brian Cheal and others at Plymouth University. Despite our best efforts some information remains elusive whilst we accept that some errors are likely to remain. Notice of any mistakes should be sent to [email protected]. The results sequence can be kept up to date by purchasing copies of the annual Local Elections Handbook, details of which can be obtained by contacting the email address above. Front cover: the graph shows the distribution of percentage vote shares over the period covered by the results. The lines reflect the colours traditionally used by the three main parties. The grey line is the share obtained by Independent candidates while the purple line groups together the vote shares for all other parties. Rear cover: the top graph shows the percentage share of council seats for the main parties as well as those won by Independents and other parties. The lines take account of any by- election changes (but not those resulting from elected councillors switching party allegiance) as well as the transfers of seats during the main round of local election. -

Dear Sir/Madam, Annwyl Syr/Madam, 28TH August 2012

230 Minutes of the meeting of Llangoedmor Community Council held at the Coracle Hall, Llechryd on Monday 4th April 2016 Present: Chairperson: Cllr Mrs Amanda Edwards. Cllrs Iwan Davies, Colin Lewis, Mrs J Hawkes, Peter Hazzelby, Bryan Rees, Mrs K Morgan County Cllr Haydn Lewis and Cllr K Symmons joined the meeting as indicated in the minutes. Members of the public: 0 1. Welcome and Apologies / Croeso ac Ymddiheuriadau Apologies had been received from Cllrs G Evans and Mrs E Davies The Chairperson welcomed everyone to the meeting. 2. Opening Prayer / Gweddi Agoriadol 3. Disclosure of Personal Interest / Datgelu Buddiannau Personol None 4. Personal Matters / Materion Personol None 5. Planning Applications / Ceisiadau Cynllunio Application A160154 Erection of Affordable Dwelling, land adjacent Talarwen, Llangoedmor Following discussion the Community Council agreed to support the application ACTION: Advise Ceredigion County Council (CCC) BY: Clerk CCC: Development Control Committee documents Noted CC H Lewis advised that CCC would remove trees and debris at the bridge when the water in the river was at a safe level. Work on the tree catcher would progress during the 16/17 financial year. It was agreed that CCC be contacted to request that work on the tree catcher be treated as a priority before damage occurred to the bridge. ACTION: Contact CCC BY: Clerk 6. Minutes of Previous Meeting / Cofnodion y Cyfarfod Blaenorol Cllr B Rees proposed that the minutes of 07.03.16 be accepted as a true record. Seconded Cllr J Hawkes, carried unanimously. 7. Matters Arising – Materion yn Codi It had been queried if the Council would provided medals for the school children to commemorate Her Majesty the Queen’s 90th birthday. -

Capel Soar-Y-Mynydd, Ceredigion

Capel Soar-y-mynydd, Ceredigion Richard Coates 2017 Capel Soar-y-mynydd, Ceredigion The chapel known as Soar-y-mynydd or Soar y Mynydd lies near the eastern extremity of the large parish of Llanddewi Brefi, in the valley of the river Camddwr deep in the “Green Desert of Wales”, the Cambrian Mountains of Ceredigion (National Grid Reference SN 7847 5328). It is some eight miles south-east of Tregaron, or more by road. Its often-repeated claim to fame is that it is the remotest chapel in all Wales (“capel mwyaf pellennig/anghysbell Cymru gyfan”). Exactly how that is measured I am not sure, but it is certainly remote by anyone in Britain’s standards. It is approached on rough and narrow roads from the directions of Tregaron, Llanwrtyd Wells, and Llandovery. It is just east of the now vanished squatter settlement (tŷ unnos) called Brithdir (whose site is still named on the Ordnance Survey 6" map in 1980-1), and it has become progressively more remote as the local sheep-farms have been abandoned, most of them as a result of the bad winter of 1946-7. Its name means ‘Zoar of the mountain’ or ‘of the upland moor’. Zoar or its Welsh equivalent Soar is a not uncommon chapel name in Wales. It derives from the mention in Genesis 19:20-30 of a place with this name which served as a temporary sanctuary for Lot and his daughters and which was spared by God when Sodom and Gomorrah were destroyed. (“Behold now, this city is near to flee unto, and it is a little one: Oh, let me escape thither, (is it not a little one?) and my soul shall live. -

Ieuenctid Y Fro Yn Llwyddo a Rhodd Hael I Elusen

Rhifyn 318 - 60c www.clonc.co.uk - Yn aelod o Fforwm Papurau Bro Ceredigion Tachwedd 2013 Papur Bro ardal plwyfi: Cellan, Llanbedr Pont Steffan, Llanbedr Wledig, Llanfair Clydogau, Llangybi, Llanllwni, Llanwenog, Llanwnnen, Llanybydder, Llanycrwys ac Uwch Gaeo a Phencarreg Clonc Cadwyn Osian ar y yn ennill Cyfrinachau brig gyda’r Eisteddfod yr Ifanc arall bowlio Tudalen 3 Tudalen 15 Tudalen 28 Ieuenctid y fro yn llwyddo a rhodd hael i elusen Caitlin Page, [ar y chwith] disgybl yn Ysgol Bro Pedr a wnaeth yn dda yn un o’r 20 a ddaeth i’r brig yn y Ras Ryngwladol ar Fynydd-dir ym mis Medi. Roedd Caitlin yn rhedeg yn y Tîm Arian. Coronwen Neal, [ar y dde] disgybl yn Ysgol Bro Bedr, Llambed a fu mewn gwersyll chwaraeon gyda’r Cadets yn Aberhonddu ar Fedi’r 28ain a 29ain a dod yn gyntaf yn y ras tair milltir. Llongyfarchiadau mawr iddi ar ei llwyddiant a phob lwc iddi yn y gystadleuaeth nesaf lle bydd hi’n cynrychioli Cymru. Y criw a gymerodd ran yn y Lap o Gymru adeg y Pasg yn trosglwyddo siec gwerth £15,255.14 i bwyllgor Llanybydder a Llambed, Ymchwil y Cancr. Yn y llun gwelir Llyr Davies a fu yn trefnu’r daith yn cyflwyno’r siec i swyddogion y pwyllgor sef Ieuan Davies, Lucy Jones a Susan Evans. Hefyd yn y llun mae nifer o’r rhai a fu yn cymryd rhan yn y daith, Rhys Jones, Tracey Davies, Kelly Davies, Emma Davies a Michelle Davies. Pedwar arall a fu’n cymryd rhan ond a fethodd â bod yn bresennol oedd Dyfrig Davies, Angharad Morgan, Llyr Jones a Mererid Davies.