Digital Cinematography: the Medium Is the Message?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jon Fauer ASC Issue 109

Jon Fauer ASC www.fdtimes.com Aug 2021 Issue 109 Art, Technique and Technology in Motion Picture Production Worldwide Aug 2021 • Issue 109 1 www.fdtimes.com Art, Technique and Technology On Paper, Online, and now on iPad Film and Digital Times is the guide to technique and technology, tools and how-tos for Cinematographers, Photographers, Directors, Producers, Studio Executives, Camera Assistants, Camera Operators, Grips, Gaffers, Crews, Rental Houses, and Manufacturers. Subscribe It’s written, edited, and published by Jon Fauer, ASC, an award-winning Cinematographer and Director. He is the author of 14 bestselling Online: books—over 120,000 in print—famous for their user-friendly way of explaining things. With inside-the-industry “secrets-of the-pros” www.fdtimes.com/subscribe information, Film and Digital Times is delivered to you by subscription or invitation, online or on paper. We don’t take ads and are supported by readers and sponsors. Call, Mail or Fax: © 2021 Film and Digital Times, Inc. by Jon Fauer Direct Phone: 1-570-567-1224 Toll-Free (USA): 1-800-796-7431 subscribe Fax: 1-724-510-0172 Film and Digital Times Subscriptions www.fdtimes.com PO Box 922 Subscribe online, call, mail or fax: Williamsport, PA 17703 Direct Phone: 1-570-567-1224 USA Toll-Free (USA): 1-800-796-7431 1 Year Print and Digital, USA 6 issues $ 49.95 1 Year Print and Digital, Canada 6 issues $ 59.95 Fax: 1-724-510-0172 1 Year Print and Digital, Worldwide 6 issues $ 69.95 1 Year Digital (PDF) $ 29.95 1 year iPad/iPhone App upgrade + $ 9.99 Film and Digital Times (normally 29.99) Get FDTimes on Apple Newsstand with iPad App when you order On Paper, Online, and On iPad a Print or Digital Subscription (above) Total $ __________ Print + Digital Subscriptions Film and Digital Times Print + Digital subscriptions continue to Payment Method (please check one): include digital (PDF) access to current and all back issues online. -

Jon Fauer ASC Issue 99 Feb 2020

Jon Fauer ASC www.fdtimes.com Feb 2020 Issue 99 Technique and Technology, Art and Food in Motion Picture Production Worldwide Photo of Claire Mathon AFC by Ariane Damain Vergallo www.fdtimes.com Art, Technique and Technology On Paper, Online, and now on iPad Film and Digital Times is the guide to technique and technology, tools and how-tos for Cinematographers, Photographers, Directors, Producers, Studio Executives, Camera Assistants, Camera Operators, Grips, Gaffers, Crews, Rental Houses, and Manufacturers. Subscribe It’s written, edited, and published by Jon Fauer, ASC, an award-winning Cinematographer and Director. He is the author of 14 bestselling books—over 120,000 in print—famous for their user-friendly way Online: of explaining things. With inside-the-industry “secrets-of the-pros” www.fdtimes.com/subscribe information, Film and Digital Times is delivered to you by subscription or invitation, online or on paper. We don’t take ads and are supported by readers and sponsors. Call, Mail or Fax: © 2020 Film and Digital Times, Inc. by Jon Fauer Direct Phone: 1-570-567-1224 Toll-Free (USA): 1-800-796-7431 subscribe Fax: 1-724-510-0172 Film and Digital Times Subscriptions www.fdtimes.com PO Box 922 Subscribe online, call, mail or fax: Williamsport, PA 17703 Direct Phone: 1-570-567-1224 USA Toll-Free (USA): 1-800-796-7431 1 Year Print and Digital, USA 6 issues $ 49.95 1 Year Print and Digital, Canada 6 issues $ 59.95 Fax: 1-724-510-0172 1 Year Print and Digital, Worldwide 6 issues $ 69.95 1 Year Digital (PDF) $ 29.95 1 year iPad/iPhone App upgrade + $ 9.99 Film and Digital Times (normally 29.99) Get FDTimes on Apple Newsstand with iPad App when you order On Paper, Online, and On iPad a Print or Digital Subscription (above) Total $ __________ Print + Digital Subscriptions Film and Digital Times Print + Digital subscriptions continue to Payment Method (please check one): include digital (PDF) access to current and all back issues online. -

THE BEST for HDR ARRI Cameras: the Ideal Route to HDR Deliverables

NEWS IBC ISSUE 2016 THE BEST FOR HDR ARRI cameras: the ideal route to HDR deliverables SKYPANEL S120-C MASTER GRIPS TRINITY The SkyPanel family grows with Ergonomic handheld control Combining mechanical stabilization a double-length LED soft light of camera and lens functions with new gimbal technology EDITORIAL DEAR FRIENDS AND COLLEAGUES For this issue we have illustrates our promise to protect customer HDR as our cover story, as it investment by prioritizing ALEXA XT owners, with is such a current topic in the various upgrade options giving them first access to industry. At ARRI we have long argued that higher the improved image quality, expanded recording dynamic range is at least as important as resolution options and new look management. when it comes to improving viewer experience, but Also in this issue Anthony Dod Mantle HDR workflows are still in their infancy and there ASC, BSC, DFF talks to us about his work on Oliver are many unresolved issues. The biggest question Stone’s Snowden, which was one of the earliest is how HDR can enhance visual storytelling, and it feature films to utilize our ALEXA 65 system and is is only the creative film and program makers who now about to hit theaters. During the intervening can answer that. Our article explores some of the period ALEXA 65 has firmly established itself as the issues and explains why – with HDR yet to be fully premier high-end motion picture camera system, established – many content producers with HDR being used on many more prestige productions, and UHD deliverables are choosing to shoot with inspiring a fruitful partnership between ARRI Rental ARRI cameras. -

Free Preview 68-69

Jon Fauer, ASC www.fdtimes.com Apr 2015 Free Preview 68-69 Art, Technique, and Technology in Motion Picture Production Worldwide Free 26 Page Preview of 96 Page Cover: Michael Keaton, Emma Stone, Emmanuel Lubezki, Alejandro González Iñárritu on Birdman. Photos by Alison Rosa © 2014 Twentieth Century Fox. Leica Summilux-C 18mm, CineTape, Preston FIZ, ARRI Alexa M. NAB 2015 Edition Birdman: Or (The Unexpected Virtue of the Unblinking Eye) them, lenses and lights to define new looks, filters and effects to degrade those looks in ways that will horrify the engineers, sensors will get bigger, with more resolution, as we viewers move closer and closer to the movie screen, monitor, tablet or phone. Some new products are not yet in this edition because their designers are racing to the finish. Some will arrive at NAB carrying prototypes, still soldering parts together in the taxi from airport to hotel. Other companies like to surprise us on opening day, revealing models under glass, pulling covers from mockups like rabbits from hats. They will astound us in press conferences and demos. AJA, Blackmagic, Cooke, Canon, Servicevision, Sony, and RED are a few of the companies with lots of buzz and rumors, cries and whispers. ARRI surprised us with a flurry of pre-NAB announcements, including the new Mini and Alexa upgrades. In this edition, Stefan Schenk, Managing Director at ARRI Cine Technik, discusses his Photo: Darren Decker © A.M.P.A.S. views on where things are and where they're going. The phone rang minutes before these pages went to press. -

NEW ARRI M8 800-Watt M8 Lamphead Rounds out the Versatile M-Series

NEWS IBC ISSUE 2013 NEW ARRI M8 800-watt M8 lamphead rounds out the versatile M-Series CFAST 2.0 FOR ALEXA XT/XR ARRISCAN ARCHIVE ULTRA WIDE ZOOM CFast 2.0 Adapter allows in-camera Century-old Mexican film footage New UWZ 9.5-18/T2.9 delivers recording to new SanDisk cards saved by ARRI archive technology exceptional super wide-angle images EDITORIAL DEAR FRIENDS AND COLLEAGUES Going into IBC we’re excited by Our new M8 lamphead expands the amazing take-up of the ALEXA XT the highly successful M-Series cameras and XR Module upgrade family of HMI fixtures equipped with since we introduced them in patented MAX Technology; we also February. Inside this issue you’ll find have another new LED Fresnel light a global overview of major movies in the L-Series – the L7-DT tuneable recording ARRIRAW in-camera to ALEXA XT/XR daylight model. On the lenses side we are proud to models, using the proven Codex workflow. You’ll unveil a remarkable Ultra Wide Zoom, and to also find details of a new CFast 2.0 Adapter for announce that the Master Anamorphic series has these models, which offers super-quick data rates begun shipping. Representing our ARRISCAN and further expands in-camera recording options. archive technologies we feature a case study in Top directors and DPs have every reason to continue these pages about the restoration of 100-year-old embracing ALEXA as the camera of choice, whatever Mexican film footage. the distribution format or resolution. Don’t forget to check in at our IBC show page We’re thrilled to have a working prototype of a arri.com/ibc2013 where you’ll find full details new camera at the show, not a successor to ALEXA about all of our products and activities at the show. -

Backlot a Final Look at the Industry Far and Wide

backlot A Final Look at the Industry Far and Wide Chris Evans, as Captain America, and director of photography McGarvey (far right) on the set of The Avengers with an ARRI film camera, which was used for select slow-motion shots. represented the biggest — and riskiest — transformation in the firm’s history. The digital cinema- ARRI CAMERAS SURVIVE tography market is extremely competitive. And, says ARRI man- aging director Franz Kraus, there was internal debate over whether THE DIGITAL REVOLUTION the venerable company was jump- Top cinematographers were anxious about abandoning film. Then the iconic camera maker ing the gun. “[Film cameras] was launched the Alexa, and it’s everywhere, from Hugo to the next Bond movie By Carolyn Giardina a market we owned,” he explains. “There was some concern within S Director oF photog- right lenses and film stock, to for Scarlett Johansson. She is a the company that it wasn’t right raphy Seamus McGarvey “I can make sure an actress is beautiful actress and looks won- to go that early into digital was preparing to shoot The going to look her best. I was derful in the film. I don’t think cameras.” A Avengers last year, he was, worried that the resolution that actors need to fear that every But now that the shift has taken he confesses, “genuinely wor- and crispness of digital would pore is going to be laid bare on the place, ARRI’s new digital cameras ried.” Because the Marvel pro- mitigate against that, producing big screen.” already have begun to win over duction — which Disney releases an effect that was too abrupt One of the most iconic brands many of the industry’s leading cin- May 4 — would require extensive for the audience.” on Hollywood film sets, ARRI ematographers — some of whom postproduction visual-effects To his surprise, McGarvey cameras have been around since first had to be convinced that work, shooting with a digital found that the Alexa digital cam- the Munich-based company was digital was a viable option. -

Andrew Conder ACS SOC Catches His Breath After Wrapping a Whirlwind First Season of the New Australian Fantasy Series the Bureau of Magical Things

SHOOTING STAR Andrew Conder ACS SOC catches his breath after wrapping a whirlwind first season of the new Australian fantasy series The Bureau of Magical Things. - by Sam Cleveland Behind the scenes on ‘The Bureau of Magical Things’ - PHOTO Supplied Andrew Conder ACS SOC behind the camera on loaction with ‘The Bureau of Magical Things’ - PHOTO Supplied The Gold Coast-based Cinematographer shot twenty heavyweights including Don McAlpine ACS ASC and Darius episodes in eighty-six days, for prolific Queensland producer Khondji AFC ASC. He was accredited by the US-based Jonathan M. Shiff, who’s sold childrens’ television to more Society of Operating Cameramen (SOC) in 2007 and got his than 170 countries. ACS letters a year later. Conder had operated the camera (and DOP’ed individual In the lead-up to The Bureau of Magical Things, Conder had episodes) on previous Shiff series including The Elephant shot four Queensland feature films including Punishment Princess (2008) where Liam Hemsworth and Margot Robbie (2008), Bullets for the Dead (2015), Nice Package (2016) and got breaks, and H2O: Just Add Water (2006-2010). He was Red Billabong (2016), as well as the ABC docu-drama Blue booked to DOP the full season of The Bureau of Magical Water Empire (2017) on the Torres Strait. Things once the decision was made to give the new series a Congratulations on The Bureau of Magical Things, bolder, more international look. AC how did you come to get the job? In the show, a teenage girl name Kyra (Brisbane’s Kimie I’d operated on quite a few of Jonathan Shiff’s previous Tsukakoshi) discovers a secret world of magic all around her, AC series and DOP’ed a few episodes, then the Bureau and becomes embroiled in a hidden struggle between elves, directors requested a new look for the show. -

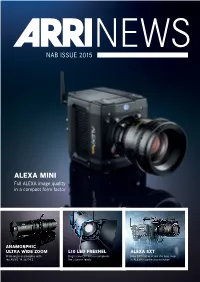

ALEXA MINI Full ALEXA Image Quality in a Compact Form Factor

NEWS NAB ISSUE 2015 ALEXA MINI Full ALEXA image quality in a compact form factor ANAMORPHIC ULTRA WIDE ZOOM L10 LED FRESNEL ALEXA SXT Wide-angle anamorphic with Bright new L10 fixture completes New SXT cameras are the next step the AUWZ 19-36/T4.2 the L-Series family in ALEXA’s continuing evolution EDITORIAL DEAR FRIENDS AND COLLEAGUES This issue of ARRI News display and even today, footage shot with ARRI is full of new products for cameras for one medium can easily be adapted for 2015, across all of our another – the recent IMAX screenings of Game of 8 various business units. With the introduction of the Thrones episodes captured with ALEXA in HD are ALEXA Mini and ALEXA 65, the announcement of a case in point. ALEXA SXT and improvements to AMIRA, we offer We’re excited to be introducing the new a camera for every different production type and SkyPanel and L10 lights, which reflect our ongoing shot requirement. Our overriding focus remains on commitment to multichannel LED technology. The future-proofing customer investment through a L10 makes the L-Series a complete family of combination of the highest image quality with the fixtures, while the SkyPanel is an entirely new most efficient workflows on set and in post. concept – one that will re-write the rules on what 4 By taking a balanced approach to the many can be achieved with LED. different parameters that determine image quality Our goal with every single new product is to we maximize compatibility with future technology fulfil the promise of the ARRI brand – a promise standards that will be defined not just by spatial that we have been keeping for nearly 100 years, of resolution, but also by higher dynamic range, uncompromising quality and long-term value for our higher frame rates and wider color gamuts. -

The Lossless Codex

Efficient workflow with High Density Encoding DISNEY CODEX Eternal sunshine of the lossless Codex In early November 2020, Zerb Managing Editor Rob Emmanuel met up – virtually – with Brian Gaffney, VP of Business Development at CODEX, an X2X Media company, to discuss the company’s latest award-winning innovation in production workflows. uring this last month, whilst speaking with the folks have now been fully integrated into the production process, prepping new projects at various camera rental from IP-based camera control and virtual sets, to the remote D facilities and post-production partners around the reviewing of dailies. One of the new technologies that has globe, I’ve started to get the feeling that the production been adopted in full force is CODEX High Density Encoding world is finally getting back to work. This is all good (HDE) in support of ARRIRAW image files. news after eight months of ‘working from home’ during The ARRI ALEXA camera system is widely used in both the pandemic. streaming television and cinema production. Its capability However, as we come back to work safely, it will become to record an uncompressed image in large format with clear that things really are different now. Word is that costs the quality of film has made it an award-winning choice below the line are up by 20–25% due to new procedures for many cinematographers; in 2019, Sir Roger Deakins that have been put in place to help protect production teams used the new ARRI ALEXA Mini LF on 1917. In fact, most from, as well as mitigate against, the effects of the COVID-19 of the Academy Award-winning features from the last 10 virus. -

ARRI ALEXA Brochure

THE MOST COMPLETE DIGITAL CAMERA SYSTEM EVER BUILT WELCOME TO THE FAMILY Where it all began: ALEXA is compact and The ALEXA Plus upgrade adds built-in affordable, with ultra-fast workflows and image wireless controls, expanded connectivity and the quality akin to 35 mm film ARRI Lens Data System 2 ALEXA is more than just a camera; it is a system platform, a family. From its very beginnings, the ALEXA family has adapted and expanded. Just as the initial model was a studied reaction to the needs of the Combining technical innovations with methodical logic, it has grown into industry, subsequent models and features have evolved in response a complete production system that can accommodate all types of to the changing landscape of digital production. workflows and all styles of filmmaking. With the camera head separated from The flagship of the range: the body, ALEXA M is optimized for 3D rigs and ALEXA Studio features an optical viewfinder, action or aerial shots a 4:3 sensor and a spinning mirror shutter 3 ALEXA IS A “I’VE BEEN A CAMERAMAN FOR MORE THAN 30 YEARS AND THIS IS THE FIRST QUANTUM LEAP IN FILMMAKING TECHNOLOGY I’VE SEEN SINCE I STARTED OUT - EVERY OTHER CHANGE HAS BEEN INCREMENTAL.” Cinematographer Robert McLachlan, CSC, ASC 4 A camera that changed everything Since the moment it was launched, ALEXA has had a profound impact on the industry, redefining the limits of digital motion picture capture with efficient workflows and incredible image quality. Adoption of the system has been widespread and swift, with the cameras in use on every possible type of production, from episodic TV shows, documentaries and high-end commercials to big- budget feature films and prestigious, international drama series. -

Arri Alexa User Manual

User Manual ARRI ALEXA For ALEXA Software Update Packet 2.0 Printed on 9 September, 2010 All rights reserved The system contains proprietary information of ARRI; it is provided under a license agreement containing restrictions on use and disclosure and is also protected by copyright law. Reverse engineering of the system is prohibited. Due to continued product development this information may change without notice. The information and intellectual property contained herein is confidential between ARRI and the client and remains the exclusive property of ARRI. If you find any problems in the documentation, please report them to us in writing. ARRI does not warrant that this document is error-free. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior written permission of ARRI. Arnold & Richter Cine Technik Tuerkenstr. 89 D-80799 Munich Germany mailto: [email protected] http://www.arri.com Contents 1 Disclaimer 4 2 Scope 7 3 ALEXA Images 8 4 Introduction to ALEXA 10 4.1 About This Manual................................................................. 12 5 Safety Instructions 13 5.1 Explanation of Warning Signs and Indications ................... 13 5.2 General Safety Instructions................................................... 13 5.3 Specific Safety Instructions................................................... 14 6 General Precautions 16 6.1 Storage and Transport.......................................................... -

All About Anamorphic

Jon Fauer, ASC www.fdtimes.com May 2015 Special Report All About Anamorphic A Review of Film and Digital Times Articles since 2007 about Anamorphic Widescreen Contents Anamorphic Ahead ..........................................................................3 Art, Technique and Technology Anamorphic 2x and 1.3x ..................................................................4 2x or 1.3x Squeeze ..........................................................................4 Film and Digital Times is the guide to technique and 2.35, 2.39, or 2.40 ..........................................................................4 technology, tools and how-tos for Cinematographers, Contempt ........................................................................................5 Photographers, Directors, Producers, Studio Executives, Contempt ........................................................................................6 2-Perf Aaton Penelope .....................................................................6 Camera Assistants, Camera Operators, Grips, Gaffers, Focal Length (spherical or anamorphic) .............................................7 Crews, Rental Houses, and Manufacturers. The Math of 4:3 and 16:9 Anamorphic Cinematography .....................9 It’s written, edited, and published by Jon Fauer, ASC, an 4:3..................................................................................................9 16:9................................................................................................9 award-winning Cinematographer