Biological Inventory of Still Creek, Burnaby

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Form 45-106F6 British Columbia Report of Exempt Distribution This

Form 45-106F6 British Columbia Report of Exempt Distribution This is the form required under section 6.1 of National Instrument 45-106 for a report of exempt distribution in British Columbia. Issuer/underwriter information Item 1: Issuer/underwriter name and contact information A. State the following: Accountable Mortgage Investment Corp. www.accountablemic.com 6245-4000 No. 3 Road Richmond BC V6X 0J8 Tel: 778-668-1972 Fax: 604-564-0480 E-mail: [email protected] B. If an underwriter is completing this report, state the following: N/A the full name of the underwriter; the underwriter’s website address; and the address, telephone number and email address of the underwriter’s head office. Item 2: Reporting issuer status A. State whether the issuer is or is not a reporting issuer and, if reporting, each of the jurisdictions in which it is reporting. The issuer is not a reporting issuer. B. If the issuer is an investment fund managed by an investment fund manager registered in a jurisdiction of Canada, name the investment fund manager and state the jurisdiction(s) where it is registered. Item 3: Issuer’s industry Indicate the industry of the issuer by checking the appropriate box below. Bio-tech Mining Financial Services exploration/development investment companies and funds production mortgage investment companies Oil and gas securitized products issuers Real estate Forestry Utilities Hi-tech Other (describe) Industrial ______________________________ Item 4: Insiders and promoters of non-reporting issuers If the issuer is an investment fund managed by an investment fund manager registered in a jurisdiction of Canada, do not complete this table. -

Indigenous History in Burnaby Resource Guide

Tsleil-Waututh community members paddling Burrard Inlet, June 18, 2014. Copyright Tsleil-Waututh Nation, Photograph by Blake Evans, 2014. Indigenous History in Burnaby Resource Guide 6501 Deer Lake Ave, Burnaby, BC V5G 3T6 | 604-297-4565 | burnabyvillagemuseum.ca 2019-06-03 The Burnaby School District is thankful to work, play and learn on the traditional territories of the hən̓q̓əmin̓əm̓ and Sḵwxwú7mesẖ speaking people. As we inquire into learning more about the history of these lands, we are grateful to Burnaby Village Museum for working with our host First Nation communities. The knowledge being shared in this resource guide through our local communities supports the teaching and learning happening in our classrooms. It deepens our understanding of the history of our community and will increase our collective knowledge of our host First Nations communities’ history in Burnaby. In our schools, this guide will assist in creating place-based learning opportunities that will build pride for our Indigenous learners through the sharing of this local knowledge, but also increase understanding for our non-Indigenous learners. Through this guide, we can move closer to the Truth and Reconciliation’s Call to Action 63 (i and iii): 63. We call upon the Council of Ministers of Education, Canada to maintain an annual commitment to Indigenous education issues, including: i. Developing and implementing Kindergarten to Grade Twelve curriculum and learning resources on Indigenous peoples in Canadian history, and the history and legacy of residential schools. iii. Building student capacity for intercultural understanding, empathy, and mutual respect. We would like extend thanks to Burnaby Village Museum staff for their time and efforts in creating this resource guide. -

Comparing Municipal Government Finances in Metro Vancouver

Comparing Municipal Government Finances in Metro Vancouver October 2014 WEST DISTRICT OF VANCOUVER NORTH VANCOUVER CITY OF NORTH VANCOUVER COQUITLAM PORT MOODY BURNABY PORT COQUITLAM VANCOUVER PITT MAPLE MEADOWS RIDGE NEW WESTMINSTER RICHMOND DISTRICT OF LANGLEY DELTA SURREY CITY OF LANGLEY WHITE ROCK Charles Lammam, Joel Emes, and Hugh MacIntyre fraserinstitute.org Contents Summary / iii Introduction / 1 1 Background / 3 2 Municipal Spending / 7 3 Municipal Revenue / 15 4 Municipal Debt and Interest Expenditures / 35 Conclusion / 39 Appendix 1 Description of the Local Government Statistics / 41 Appendix 2 Spending and Revenue per Person by Major Category / 45 Appendix 3 Municipal Summary Profiles, 2012 / 47 References / 56 About the Authors / 59 Publishing Information 60 Acknowledgments / 60 Supporting the Fraser Institute 61 Purpose, Funding, and Independence / 62 About the Fraser Institute / 63 Editorial Advisory Board / 64 fraserinstitute.org / i fraserinstitute.org Summary Municipal governments play an important role in the lives of British Columbians by providing important services and collecting taxes. But municipal finances do not receive the same degree of public scrutiny as more senior governments. This can pose a problem for taxpayers and voters who want to understand how their municipal government performs, especially compared to other municipalities. To help create awareness and encourage debate, this report provides a summary analysis of important financial information for 17 of the 21 municipal- ities in Metro Vancouver, spanning a 10-year period (2002–2012). The intention is not to make an assessment of any municipality’s finances—for instance, whether taxes or spending are too high or whether municipal governments produce good value for taxpayers. -

For Lease Prime Retail Space with Skytrain Exposure

FOR LEASE PRIME RETAIL SPACE WITH SKYTRAIN EXPOSURE 567 & 581 CLARKE ROAD COQUITLAM, BC BURQUITLAM Skytrain Platform Partnership. Performance. Max Ripper, Associate Daniel Lee*, Principal 604.647.1348 604.757.5102 [email protected] [email protected] *Daniel J. Lee Personal Real Estate Corporation SIGNAGE SIGNAGE EXECUTIVE SUMMARY OPPORTUNITY 567 & 581 Clarke Road Municipal Address Coquitlam, BC Avison Young is pleased to present an exceptional opportunity to lease 567-581 Clarke Road located in the thriving Burquitlam Timing Q3 2020 market. The subject property features prime retail space located with direct exposure to the Burquitlam Platform 2 SkyTrain CRU 1 5,571 sf Station. 567-581 Clarke Road is the new commercial hub for the CRU 2 2,394 sf Burquitlam area featuring immediate access to Simon Fraser CRU 3 3,662 sf University, Metrotown City Centre and Downtown Vancouver. Unit Units Available Demising and contiguous options CRU 4 1,924 sf sizes range from 1,939 sf – 5,571 sf with the largest contiguous available for all units space being 7,965 sf. The units will be provided in shell condition CRU 5 1,939 sf ready for tenant improvements. CRU 6 2,134 sf Total 17,624 sf KEY HIGHLIGHTS Ceiling Heights Approx. 27 feet Located within 1-minute walk to Burquitlam Station Platform 2 SkyTrain Station Commercial Parking 61 stalls Thriving neighbourhood with significant redevelopment Asking Rate Please contact listing agent Across from newly built 35,000 sf Safeway Extra Additional Rent $20.00 psf (2020 estimate) Excellent exposure on Clarke Road and Como Lake Avenue U N I T S AVAILABLE FLOOR PLAN CRU 1 –5,571 sf CRU 5 – 1,939 sf CRU 2 – 2,394 sf CRU 6 – 2,134 sf CRU 3 – 3,662 sf CRU 4 – 1,924 sf CRU 1 CRU 2 CRU 3 CRU 4 CRU 5 CRU 6 SIGNAGE SIGNAGE W I T H I N 3 K M RADIUS POPULATION GROWTH (NEXT 5 YEARS) 10.8% AVERAGE INCOME $93,200 DAYTIME POPULATION 57,223 DOMINANT EDUCATION LEVEL Bachelor Degree NEW CONDOMINIUM UNITS in the immediate area OVER 1,000 SIGNAGE SIGNAGE SIGNAGE SIGNAGE POPULATION GROWTH (NEXT 5 YEARS) SIGNAGE T E L N I D R A R BAY ST. -

NO.5 ROAD [email protected] 604 662 5147

FOR LEASE: 94,035 SQ.FT. WAREHOUSE WITH DOCK AND GRADE LOADING IN SOUTH RICHMOND. THE INDUSTRIAL SPECIALISTS Joel Barnett Personal Real Estate Corporation [email protected] 11511 604 662 5570 Steve Brooke Personal Real Estate Corporation NO.5 ROAD [email protected] 604 662 5147 RICHMOND | BC theindustrialspecialists.com CBRE Limited, 1021 West Hastings Street, Suite 2500, Vancouver, BC, V6E 0C3, EFFICIENT ACCESS TO ALL AREAS OF METROLOCATION VANCOUVER: DETAILS The property sits in the heart of Riverside Industrial Park in South Richmond.EFFICIENT This highly ACCESS convenient TO locationALL AREAS is situated seconds OF METRO VANCOUVER: RIVERSIDE11511 away from the intersection of Steveston Highway and Highway 99 to VancouverThe andproperty the U.S sits border in the crossing.heart of OccupantsRiverside Industrial will enjoy Park in NO.5 ROAD convenientSouth access Richmond. to public transitThis highly routes convenient along No. location 5 Road isand situated RICHMOND, BRITISH COLUMBIA Steveston secondsHighway awayconnecting from thedirectly intersection to downtown of Steveston Richmond Highway and the Canadaand Highway Line SkyTrain. 99 to Vancouver Occupants and will the also U.S benefit border from crossing. INDUSTRIAL PARK the nearbyOccupants Ironwood willPlaza enjoy with convenientover 35 unique access retail to publicstores, transit routes along No. 5 Road and Steveston Highway that restaurants, banks and amenities. connect directly to downtown Richmond and the Canada Line SkyTrain. Occupants will also benefit from the nearby TRAVEL TIMESIronwood : Plaza with over 35 unique retail stores, restaurants, banksMIN and other services. MIN TO RICHMOND TO YVR 12TRAVEL CENTRE TIMES : 15 AIRPORT MIN MIN MIN MIN TO DELTAPORTTO RICHMOND TO CAN/USATO YVR 2012 GCT CENTRE 2515 BORDER CROSSING AIRPORT 11511 NO.5 ROAD MIN MIN TO DELTAPORT TO CAN/USA 20 GCT 25 BORDER CROSSING NEARBY BUSINESSES AND AMENITIES : 1. -

Contact & Address Info

Aids to Independent Living Program, Phone: (604) 859-5960 Info & Address Contact Canadian Red Cross Website: redcross.ca Alcohol and Drug Information Referral Phone (toll-free): 1-800-663-1441 Assisted Living Registrar, Ministry of Phone (toll-free): 1-866-714-3378 Health Website: health.gov.bc.ca Address: 300-1275 West 6th Avenue, Vancouver, BC V6H 1A6 Auburn Residences in Chilliwack Phone: 604-792-3545 Website: retirementconcepts.com Address: 8531 Young Road, Chilliwack, BC, V2P 0E1 BC 211 Phone: 2-1-1 BC Association of Community Response Website: bccrns.ca Networks (BCCRNS) BC Centre for Elder Advocacy and Sup- Phone (toll-free): 1-866-437-1940 port (BCCEAS) Hearing impaired [TTY] 1-855-306-1443 Website: bcceas.ca Address: 150-900 Howe Street, Vancouver, BC V6E 2R1 BC Elders’ Guide, First Nations Health Phone: 1-866-913-0033 Authority & BC Ministry of Health Website: seniorsbc.ca BC Housing Website: bchousing.org Chilliwack Seniors' Living Well Resource Guide 81 BC Old Age Pensioners Organization #173- Sardis Info & Address Contact Phone: (604) 858-4066 Address: 5725 Tyson Road, Sardis, BC V2R 3R6 #164- Cultus Lake Phone: (604) 858-7633 Address: Cultus Lake Community Hall, 4220 Columbia Valley Highway, Cultus Lake, BC V2R 5B6 BC Palliative Care Benefits Program Website: health.gov.bc.ca BC Securities Commission, Scams and Phone: (toll-free): 1-800-373-6393 Fraud Website: investright.org BC Senior’s Fishing License Website: fishing.gov.bc.ca BC Seniors Games Society, 55+ BC Phone: 604-824-7963 Games Website: bcseniorsgames.org BC Seniors’ -

Guide to Resources in Burnaby

Employee Health & Wellness Guide to Resources in Burnaby 1 Employee Health & Wellness Resource Guide Table of Contents: Table of Contents: ......................................................................................................................................... 2 Employee & Family Assistance Program (EFAP) Morneau Shepell: .............................................................. 4 Salary Indemnity Plan for BTA Members ...................................................................................................... 5 Teacher Rehabilitation Program ................................................................................................................... 5 Joint Early Intervention Services (JEIS) – CUPE ............................................................................................. 6 Pacific Blue Cross .......................................................................................................................................... 6 HealthLink BC ................................................................................................................................................ 7 BC HealthGuide ............................................................................................................................................. 7 Find a Doctor ................................................................................................................................................. 7 Medical Interpreting Services ...................................................................................................................... -

Habitat Connectivity and Restoration Potential Assessment of Deer Lake

Habitat Connectivity and Restoration Potential Assessment of Deer Lake Brook in Burnaby, BC Review of the Connection Between Two Western painted turtle Occupied Sites in an Urban Environment April 2012 Prepared by Aimee Mitchell and Deanna MacTavish of the The South Coast Western Painted Turtle Recovery Project For Kym Welstead, Ministry of Environment, Surrey, BC and Joanne Neilson, BC Conservation Foundation, Surrey, BC Table of Contents 1.0 INTRODUCTION.................................................................................................................................................... 1 2.0 AREA ..................................................................................................................................................................... 1 2.1 Historical and Current Use ................................................................................................................................ 1 2.2 Current Site Description ................................................................................................................................... 3 3.0 RESEARCH INFORMATION .................................................................................................................................... 5 3.1 Physical Data ..................................................................................................................................................... 5 3.1.1 Historical ................................................................................................................................................... -

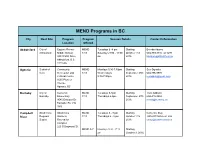

MEND Programs in BC

MEND Programs in BC City Host Site Program Program Session Details Contact Information Location Offered Abbotsford City of Eugene Reimer MEND Tuesdays 6 8 pm Starting Brenda Adams Abbotsford Middle School 713 Saturdays 9:00 11:00 October 11th 6048593134 ext 5297 3433 Firhill Drive, am 2016 [email protected] Abbotsford, B.C. V2T 6X6 Agassiz District of Community MEND Mondays 5:307:30pm Starting Sue Ogroske Kent Recreation and 713 Wednesdays September 28th 6047968891 Cultural Centre 5:307:30pm 2016 [email protected] 6660 Pioneer Avenue Agassiz, BC Burnaby City of Cameron MEND Tuesdays 68pm Starting Traci Addison Burnaby Elementary 713 Thursdays 68pm September 27th 6044153559 9540 Erickson Dr, 2016 [email protected] Burnaby, BC V3J 1M9 Campbell Strathcona Strathcona MEND Tuesdays 6 8 pm Starting Catherine May River Regional Gardens 713 Thursdays 6 8 pm October 11th 2502879234 ext. 226 District Recreation 2016 [email protected] Complex 225 S Dogwood St, MEND 57 Mondays 5:30 7:15 Starting pm October 3, 2016 Campbell River, BC V9W 2Y1 Chilliwack Chilliwack Chilliwack MEND Thursdays 6:00pm – Starting [email protected] Family Neighbourhood 713 8:00pm October 1,, 6047014978 ext. 6043 YMCA Learning Centre Saturdays 2016 46361 Yale Road 10:30am12:30pm Chilliwack, BC V2P 2R1 Coquitlam YMCA of Pinetree MEND Tuesdays 5:457:45pm Starting Serena Bring Greater Community Centre 713 Saturdays 2:304:30 September 27, [email protected] Vancouver 1260 Pinetree Way, 2016 6043205826 Coquitlam, BC V3B 7Z4 Cranbrook -

Christmas Tradition - a Combination of Charlie’S Maraschino Cherries & Snowballs (Vanilla Cream, Rolled in Dark Chocolate & Coconut)

BURNABY PORT COQUITLAM 3746 Canada Way 2 - 1770 McLean Ave Burnaby, BC V5G 1G4 Port Coquitlam, BC V3C 4K8 T: 604-437-8221 T: 604-941-3811 General Inquiries: [email protected] Order Desk: [email protected] www.CharliesChocolateFactory.com Charlies Specialties Assorted Chocolates & Salted Nuts* 1 lb. Box (#101) $26.00 2 lb. Box (#102) $52.00 Nuts & Caramels* Variety of chocolate covered nuts and caramels. 1/2 lb. Box (#103) $14.50 1 lb. Box (#104) $28.00 Soft Centers* Staying away from hard, chewy centers? This box has a variety of chocolates with fillings such as Jellies, Meltaways & Creams. 1/2 lb. Box (#105) $14.50 1 lb. Box (#106) $28.00 2 Salted Caramels Each chewy caramel square is enrobed in Belgian chocolate & sprinkled with Himalayan Sea Salt. 12 pc. Box (#107) $13.00 Nuts & Caramels* Variety of chocolate covered nuts and caramels. Assorted Chocolates* A classic selection of Charlie’s specialties! The Assorted Box is packed with a selection of everything at Charlie’s... A little something for everyone. 1/2 lb. Box (#108) $14.50 2 lb. Box (#111) $56.00 1 lb. Box (#109) $28.00 3 lb. Box (#112) $84.00 1 1/2 lb. Box (#110) $42.00 5 lb. Box (#113) $140.00 * Asterisk indicates that boxes come gift wrapped. 3 Snowballs & Cherries* A Christmas tradition - a combination of Charlie’s Maraschino Cherries & Snowballs (vanilla cream, rolled in dark chocolate & coconut). 1/2 lb. Style Box (#114) $14.50 Ginger* Candied Ginger pieces from Fiji enrobed in Belgian chocolate. 1/2 lb. -

Hall of Champions

Hall of Champions Athlete awards U15 Female Athlete of the Year (previously Bantam U14) 2016 - Samantha Loutet (Burnaby, canoe) 2000 - Gillian Fedechko (Ridge) and Cassidy MacPherson (Ridge, kayak) 1999 - not awarded 2015 - Hana Roayne (Pemberton) 1998 - Bronwyn Arundel (Ridge) 2014 - Melody Oh (Ridge) 1997 - Bronwyn Arundel (Ridge) 2013 - Ayla Mark (Nanaimo) 1996 - Jordan Einarson (Ridge) 2012 - Ayla Mark (Nanaimo) 1995 - Jordan Einarson (Rdige) 2011 - Isobel Glover (Victoria Youth) 1994 - Catherine Shandler (Kamloops) 2010 - Brook McLean (Kamloops) 1993 - Patricia Ploch (Ridge) 2009 - Olivia Cavasinni (Ridge) 1992 - Jennifer Lovatt (Ridge) 2008 - Olivia Cavasinni (Ridge) 1991 - Jennifer Lovatt (Ridge) & Bree 2007 - Sara Mitchell (Ridge) Forsythe (Kamloops 2006 - Jessica Mitchell (Ridge) 1990 - Ashley Rowe (Nanaimo) 2005 - Kiran Basra (Burnaby) 1989 - Rachel May (Nanaimo) 2004 - Maggie Henderson (Ridge) 1988 - Lara Lindal (Burnaby) 2003 - Kristin Bauder (Fort Langley) 1987 - Lara Lindal (Burnaby) 2002 - Sara Wray (Pemberton) 1986 - Sheelagh Toop (Burnaby) 2001 - not awarded U15 Male Athlete of the Year (previously Bantam U14) 2016 - Stanley Netherton (Kamloops, 2007 - Brian Malfesi (Ridge) & Matthew kayak) and Quinn Phare (Pemberton, Kuran (Ridge) canoe) 2006 - Jordan Traas (Fort Langley) & 2015 - Tyler Demidoff (Ridge) Matthew Kuran (Ridge) 2014 - Cameron Antifave (Nanaimo) 2005 - Conor Wollbaum (Burnaby) 2013 - Justin Won (Ridge) 2004 - Ken Muir (Ridge) 2012 - Cameron Antifave (Nanaimo) 2003 - Sean McBeath (Ridge) & Doug 2011 - Omar -

BRUNETTE CREEK NEIGHBOURHOOD PLANNING STUDY ENVIRONMENTAL REVIEW Final Report

THE CITY OF NEW WESTMINSTER BRUNETTE CREEK NEIGHBOURHOOD PLANNING STUDY ENVIRONMENTAL REVIEW Final Report Prepared by: Gartner Lee Limited Engineering and In Association with: Planning Consultants G.D. Hamilton Associates Limited and Ian Chang Consulting Planner THE CITY OF NEW WESTMINSTER Brunette Creek Neighbourhood Planning Study Environmental Review ISO 9001 Registered Quality Assured This Study consists of three reports under separate covers: Gartner Lee Limited Engineering and Planning Consultants In Association with: 9th Floor 1199 West Hastings G.D. Hamilton Associates Vancouver Consulting Ltd. British Columbia Canada V6E 3T5 and Telephone: 604 / 684 4488 Facsimile: 604 / 684 5908 Ian Chang email [email protected] Consulting Planner www.gdhamilton.com October 2001 GLL 20751 BRUNETTE CREEK NEIGHBOURHOOD PLANNING STUDY ENVIRONMENTAL REVIEW – FINAL REPORT TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 INTRODUCTION................................................................................................................1 1.1 Background.................................................................................................................... 1 1.2 Study Objectives ............................................................................................................ 1 2.0 STUDY METHODOLOGY .................................................................................................2 3.0 STUDY FINDINGS.............................................................................................................4 3.1 Contaminated Sites.......................................................................................................