Handbook Ver 7

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Southern Comfort

FROM THE NATIONAL ALLIANCE FOR MUSICAL THEAtre’s PresideNT Welcome to our 24th Annual Festival of New Musicals! The Festival is one of the highlights of the NAMT year, bringing together 600+ industry professionals for two days of intense focus on new musical theatre works and the remarkably talented writing teams who create them. This year we are particularly excited not only about the quality, but also about the diversity—in theme, style, period, place and people—represented across the eight shows that were selected from over 150 submissions. We’re visiting 17th-century England and early 20th century New York. We’re spending some time in the world of fairy tales—but not in ways you ever have before. We’re visiting Indiana and Georgia and the world of reality TV. Regardless of setting or stage of development, every one of these shows brings something new—something thought-provoking, funny, poignant or uplifting—to the musical theatre field. This Festival is about helping these shows and writers find their futures. Beyond the Festival, NAMT is active year-round in supporting members in their efforts to develop new works. This year’s Songwriters Showcase features excerpts from just a few of the many shows under development (many with collaboration across multiple members!) to salute the amazing, extraordinarily dedicated, innovative work our members do. A final and heartfelt thank you: our sponsors and donors make this Festival, and all of NAMT’s work, possible. We tremendously appreciate your support! Many thanks, too, to the Festival Committee, NAMT staff and all of you, our audience. -

Royal Opera House Performance Review 2006/07

royal_ballet_royal_opera.qxd 18/9/07 14:15 Page 1 Royal Opera House Performance Review 2006/07 The Royal Ballet - The Royal Opera royal_ballet_royal_opera.qxd 18/9/07 14:15 Page 2 Contents 01 TH E ROYA L BA L L E T PE R F O R M A N C E S 02 TH E ROYA L OP E R A PE R F O R M A N C E S royal_ballet_royal_opera.qxd 18/9/07 14:15 Page 3 3 TH E ROYA L BA L L E T PE R F O R M A N C E S 2 0 0 6 / 2 0 0 7 01 TH E ROYA L BA L L E T PE R F O R M A N C E S royal_ballet_royal_opera.qxd 18/9/07 14:15 Page 4 4 TH E ROYA L BA L L E T PE R F O R M A N C E S 2 0 0 6 / 2 0 0 7 GI S E L L E NU M B E R O F PE R F O R M A N C E S 6 (15 matinee and evening 19, 20, 28, 29 April) AV E R A G E AT T E N D A N C E 91% CO M P O S E R Adolphe Adam, revised by Joseph Horovitz CH O R E O G R A P H E R Marius Petipa after Jean Coralli and Jules Perrot SC E N A R I O Théophile Gautier after Heinrich Meine PRO D U C T I O N Peter Wright DE S I G N S John Macfarlane OR I G I N A L LI G H T I N G Jennifer Tipton, re-created by Clare O’Donoghue STAG I N G Christopher Carr CO N D U C T O R Boris Gruzin PR I N C I PA L C A S T I N G Giselle – Leanne Benjamin (2) / Darcey Bussell (2) / Jaimie Tapper (2) Count Albrecht – Edward Watson (2) / Roberto Bolle (2) / Federico Bonelli (2) Hilarion – Bennet Gartside (2) / Thiago Soares (2) / Gary Avis (2) / Myrtha – Marianela Nuñez (1) / Lauren Cuthbertson (3) (1- replacing Zenaida Yanowsky 15/04/06) / Zenaida Yanowsky (1) / Vanessa Palmer (1) royal_ballet_royal_opera.qxd 18/9/07 14:15 Page 5 5 TH E ROYA L BA L L E T PE R F O R M A N C E S 2 0 0 6 / 2 0 0 7 LA FI L L E MA L GA R D E E NU M B E R O F PE R F O R M A N C E S 10 (21, 25, 26 April, 1, 2, 4, 5, 12, 13, 20 May 2006) AV E R A G E AT T E N D A N C E 86% CH O R E O G R A P H Y Frederick Ashton MU S I C Ferdinand Hérold, freely adapted and arranged by John Lanchbery from the 1828 version SC E N A R I O Jean Dauberval DE S I G N S Osbert Lancaster LI G H T I N G John B. -

English 252: Theatre in England 2006-2007 * [Optional Events

English 252: Theatre in England 2006-2007 * [Optional events — seen by some] Wednesday December 27 *2:30 p.m. Guys and Dolls (1950). Dir. Michael Grandage. Music & lyrics by Frank Loesser, Book by Jo Swerling and Abe Burrows. Based on a story and characters of Damon Runyon. Designer: Christopher Oram. Choreographer: Rob Ashford. Cast: Alex Ferns (Nathan Detroit), Samantha Janus (Miss Adelaide), Amy Nuttal (Sarah Brown), Norman Bowman (Sky Masterson), Steve Elias (Nicely Nicely Johnson), Nick Cavaliere (Big Julie), John Conroy (Arvide Abernathy), Gaye Brown (General Cartwright), Jo Servi (Lt. Brannigan), Sebastien Torkia (Benny Southstreet), Andrew Playfoot (Rusty Charlie/ Joey Biltmore), Denise Pitter (Agatha), Richard Costello (Calvin/The Greek), Keisha Atwell (Martha/Waitress), Robbie Scotcher (Harry the Horse), Dominic Watson (Angie the Ox/MC), Matt Flint (Society Max), Spencer Stafford (Brandy Bottle Bates), Darren Carnall (Scranton Slim), Taylor James (Liverlips Louis/Havana Boy), Louise Albright (Hot Box Girl Mary-Lou Albright), Louise Bearman (Hot Box Girl Mimi), Anna Woodside (Hot Box Girl Tallulha Bloom), Verity Bentham (Hotbox Girl Dolly Devine), Ashley Hale (Hotbox Girl Cutie Singleton/Havana Girl), Claire Taylor (Hot Box Girl Ruby Simmons). Dance Captain: Darren Carnall. Swing: Kate Alexander, Christopher Bennett, Vivien Carter, Rory Locke, Wayne Fitzsimmons. Thursday December 28 *2:30 p.m. George Gershwin. Porgy and Bess (1935). Lyrics by DuBose Heyward and Ira Gershwin. Book by Dubose and Dorothy Heyward. Dir. Trevor Nunn. Design by John Gunter. New Orchestrations by Gareth Valentine. Choreography by Kate Champion. Lighting by David Hersey. Costumes by Sue Blane. Cast: Clarke Peters (Porgy), Nicola Hughes (Bess), Cornell S. John (Crown), Dawn Hope (Serena), O-T Fagbenie (Sporting Life), Melanie E. -

January 2018 :: Sightlines :: USITT

January 2018 :: Sightlines :: USITT January 2018 Print this page › NEWS & NOTICES: Tweet Share Lead story › Member Spotlight: Mark Putman Member Spotlight: Mark Putman Fellows of the Institute Q&A with production manager and sound designer for Missouri State University and member of USITT’s Heart of America Regional Section, The Green Scene Mark Putman... more » 2018 Student Ambassador Mentors New Fellows AIDS Memorial Quilt USITT will induct three new Fellows into the Institute at USITT 2018 in Fort Lauderdale: Dan Culhane, Travis De Castro, and Susan Tsu... Tri-Annual Art Auction more » In Memoriam: Doris Siegel, David William Weiss The Green Scene Announcements Dathan Powell focuses on the work of young artists who recognize the prospect of sustainable theatre making an impact in disciplines other INTERNATIONAL: than our own... more » PQ 2019 Design Exhibit Winners Student Ambassador International Guests 2018 NEWS FROM: Three international guests will join select student ambassadors in Fort Executive Director Lauderdale to bring a global perspective to USITT 2018... more » Spotlight on Giving: Tammy Honesty AIDS Quilt Information President Do you know any of these names? Help complete this memorial by providing bios and anecdotes to be featured in TD&T... more » LAST WORD: Conference Deadline Is Tri-Annual Art Auction and Garage Sale at USITT 2018 Coming! Have artwork or books that are collecting dust at home? Consider FOR THE RECORD: donating them to the Tri-Annual Art Auction and Garage Sale for others Leadership to enjoy... more » Contributing Members PQ 2019 Design Exhibit Winners Sustaining Members Winners of the 2019 Prague Quadrennial Design Exhibit are announced.. -

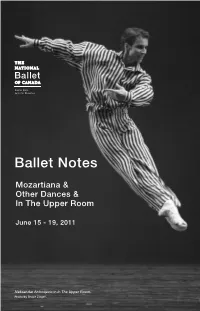

Ballet Notes

Ballet Notes Mozartiana & Other Dances & In The Upper Room June 15 - 19, 2011 Aleksandar Antonijevic in In The Upper Room. Photo by Bruce Zinger. Orchestra Violins Bassoons Benjamin BoWman Stephen Mosher, Principal Concertmaster JerrY Robinson LYnn KUo, EliZabeth GoWen, Assistant Concertmaster Contra Bassoon DominiqUe Laplante, Horns Principal Second Violin Celia Franca, C.C., Founder GarY Pattison, Principal James AYlesWorth Vincent Barbee Jennie Baccante George Crum, Music Director Emeritus Derek Conrod Csaba KocZó Scott WeVers Karen Kain, C.C. Kevin Garland Sheldon Grabke Artistic Director Executive Director Xiao Grabke Trumpets David Briskin Rex Harrington, O.C. NancY KershaW Richard Sandals, Principal Music Director and Artist-in-Residence Sonia Klimasko-LeheniUk Mark Dharmaratnam Principal Conductor YakoV Lerner Rob WeYmoUth Magdalena Popa Lindsay Fischer JaYne Maddison Trombones Principal Artistic Coach Artistic Director, Ron Mah DaVid Archer, Principal YOU dance / Ballet Master AYa MiYagaWa Robert FergUson WendY Rogers Peter Ottmann Mandy-Jayne DaVid Pell, Bass Trombone Filip TomoV Senior Ballet Master Richardson Tuba Senior Ballet Mistress Joanna ZabroWarna PaUl ZeVenhUiZen Sasha Johnson Aleksandar AntonijeVic, GUillaUme Côté*, Violas Harp Greta Hodgkinson, Jiˇrí Jelinek, LUcie Parent, Principal Zdenek KonValina, Heather Ogden, Angela RUdden, Principal Sonia RodrigUeZ, Piotr StancZYk, Xiao Nan YU, Theresa RUdolph KocZó, Timpany Bridgett Zehr Assistant Principal Michael PerrY, Principal Valerie KUinka Kevin D. Bowles, Lorna Geddes, -

Sardono Dance Theater and Jennifer Tipton: Rain Coloring Forest

SARDONO DANCE THEATER AND JENNIFER TIPTON: RAIN COLORING FOREST SEPTEMBER 16 – 18, 2010 | 8:30 PM SEPTEMBER 19, 2010 | 3:00 PM presented by REDCAT Roy and Edna Disney/CalArts Theater California Institute of the Arts SARDONO DANCE THEATER AND JENNIFER TIPTON: RAIN COLORING FOREST WORLD PREMIERE Directed, choreographed and performed by Sardono W. Kusumo Artwork by Sardono W. Kusumo Lighting Designed by Jennifer Tipton Original music composed and performed by David Rosenboom Digital Projections by Maureen Selwood Dance and vocals Bambang “Besur” Suryono Dancer I Ketut Rina Assistant lighting designer Iskandar K. Loedin Animation assistants Meejin Hong and Joanna Leitch Produced by REDCAT (Roy and Edna Disney/CalArts Theater) Rain Coloring Forest Managing Producer: Laura Kay Swanson Production Crew: Ernie Mondaca, Israel Mondaca, Patrick Traylor, Tiffany Williams Special thanks to The Consulate General of the Republic of Indonesia in Los Angeles , Mr. Arifin Panigoro, Astra Price, Nathan Ruyle and Linda Wissmath. Rain Coloring Forest is made possible by the Contemporary Art Centers (CAC) network, administered by the New England Foundation for the Arts (NEFA), with major support from the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation. CAC is comprised of leading art centers, and brings together performing arts curators to support collaboration and work across disciplines, and is an initiative of NEFA’s National Dance Project. BIOGRAPHIES Sardono W. Kusumo (Director and Choreographer) has been acclaimed as one of the most cutting- edge contemporary choreographers and brilliant theatrical imagists of Asia, even at the beginning of his artistic career. He has been credited by Michel Cournot of Le Monde (Paris) as the creator of the five most captivating yet silent minutes of the Festival Mondiale at the Théâtre de Nancy (1973). -

Trisha Brown 1936-2017 Founding Artistic Director & Choreographer

© Marc Ginot, 2010 TRISHA BROWN 1936-2017 FOUNDING ARTISTIC DIRECTOR & CHOREOGRAPHER One of the most acclaimed and influential choreographers and dancers of her time, Trisha Brown’s groundbreaking work forever changed the landscape of art. From her roots in rural Aber- deen, Washington, her birthplace, Brown arrived in New York in 1961. A student of Anna Halprin, Brown participated in the choreographic composition workshops taught by Robert Dunn – from which Judson Dance Theater was born – greatly contributing to the fervent of interdisciplinary cre- ativity that defined 1960s New York. Expanding the physical behaviors that qualified as dance, she discovered the extraordinary in the everyday, and brought tasks, rulegames, natural movement and improvisation into the making of choreography. With the founding of the Trisha Brown Dance Company in 1970, Brown set off on her own distinc- tive path of artistic investigation and ceaseless experimentation, which extended for forty years. The creator of over 100 choreographies, six operas, and a graphic artist, whose drawings have earned recognition in numerous museum exhibitions and collections, Brown’s earliest works took impetus from the cityscape of downtown SoHo, where she was a pioneering settler. In the 1970s, as Brown strove to invent an original abstract movement language – one of her singular achieve- ments – it was art galleries, museums and international exhibitions that provided her work its most important presentation context. Indeed, contemporary projects to introduce choreography to the museum setting are unthinkable apart from the exemplary model that Brown established. Brown’s movement vocabulary, and the new methods that she and her dancers adopted to train their bodies, remain one of her most pervasively impactful legacies within international dance practice. -

December 2019 Welcome Mike Hausberg

DECEMBER 2019 WELCOME MIKE HAUSBERG Welcome to The Old Globe and this production of Ebenezer Scrooge’s BIG San Diego Christmas Show. Our goal is to serve all of San Diego and beyond through the art of theatre. Below are the mission and values that drive our work. We thank you for being a crucial part of what we do. MISSION STATEMENT The mission of The Old Globe is to preserve, strengthen, and advance American theatre by: creating theatrical experiences of the highest professional standards; producing and presenting works of exceptional merit, designed to reach current and future audiences; ensuring diversity and balance in programming; providing an environment for the growth and education of theatre professionals, audiences, and the community at large. STATEMENT OF VALUES The Old Globe believes that theatre matters. Our commitment is to make it matter to more people. The values that shape this commitment are: TRANSFORMATION Theatre cultivates imagination and empathy, enriching our humanity and connecting us to each other by bringing us entertaining experiences, new ideas, and a wide range of stories told from many perspectives. INCLUSION The communities of San Diego, in their diversity and their commonality, are welcome and reflected at the Globe. Access for all to our stages and programs expands when we engage audiences in many ways and in many places. EXCELLENCE Our dedication to creating exceptional work demands a high standard of achievement in everything we do, on and off the stage. STABILITY Our priority every day is to steward a vital, nurturing, and financially secure institution that will thrive for generations. -

Reaching New Audiences from School to Career

Volume LV Number 1 • Winter 2014 • $8.00 INSIDE: 2014 College, University & Professional Training Program Directory Reaching New Audiences Site-Specific Theatre: The Place Is the Thing Younger Artists ‘Make Theatre Happen’ From School To Career 10 Things Emerging Artists Need to Know ... BFA Design and theatre technology | BFA Production and stage Management Design Your Future BA theatre | BFA theatre Performance and Musical theatre Act now! Photo: 2010 Production of Machinal, by Sophie Treadwell, Directed by Heather May. Contact: C OLLEGE OF L IBERAL A RTS Department of Theatre Dr. scott Phillips, chair, Department of theatre tel [email protected] 334.844.4748 www.auburnuniversitytheatre.org www.auburn.edu | Auburn University is an equal opportunity educational institution/employer. PLAY WEST PLAY TRE HEA CO T M G PA W N U Y UWG THEATRE COMPANY Exceptional Training in a Professional Environment P LAY WEST NAST Accredited Bachelor of Arts Degree in Theatre UWG THEATRE OFFERS: • Access to professional theatre artists Call 678-839-4700 or • Access to industry standard software in theatrical sound, lighting, costume, e-mail [email protected] and scenic design • Performance and design opportunities starting in freshman year for more information. • Design lab, lighting lab, sound recording studio, large scene shop, and new costume shop www.westga.edu/~theatre • Internship programs (local, national, international) • Practical experience in all facets of theatrical production • Student scripts from playwriting course are produced in regular -

MISS SAIGON: LONDON's LATESTDAZZLER Julian Williams Scoops the Technical Story from Lighting Designer David Hersey

MISS SAIGON: LONDON'S LATESTDAZZLER Julian Williams scoops the technical story from lighting designer David Hersey September 25th saw the opening, at the some time, going through a number of with stuff. Theatre Royal Drury Lane, of the much drafts, and was designed last year - in a "Obviously , as anyone who has been heralded new musical 'Miss Saigon' by Alain completely different form from the one we around for a while will know , you do Boublil and Claude-Michel Schonberg, are now doing. develop a kind of style of your own. There directed by Nicholas Hytner. The designer "I began serious work on it in April this year are certain kinds of ingredients you like to was John Napier, and lighting designer David to develop the rig," he continued . "The have around as part of your 'kit'. And those Hersey. model was available, and there were certain ingredients you tend to develop from show known elements for a long time . The idea of to show - so there are not always the same The show's opening scene pictures Saigon in using a helicopter was developed some time ingredients, but there is a kind of logical pro 1975 as the last of the Ame ricans are prepar ago, as was the idea of using moving screens gression. The light curtain is a case in point." ing to leave, and in the Dreamland Night on each side. While talking about equipment , I asked Club there is a 'Miss Saigon' competition in "John Napier's ideas of the set were well David Hersey if there was anything in this progress. -

Catalogue 47 Vs 5.Qxd

COLOUR FILTERS FOG Swatchbooks . .3 Fog Machines . .46 Supergel . .4 Fog Fluids . .52 Roscolux . .6 E-Colour+ . .8 Cinegel . .10 RoscoView . .18 PAINT RoscoShades . .19 Scenic Paints . .54 Cinegel Kits . .20 Coatings and Glazes . .58 Permacolor . .21 Roscoflamex . .60 Filter Accessories . .23 Paint Accessories . .61 Digital Compositing . .62 BACKDROPS/DIGITAL IMAGING .24 TV/Video Paints . .63 GOBOS STAGE HARDWARE . .64 Steel . .26 Glass . .28 FLICKER CANDLES . .65 Gobo Accessories . .32 FLOOR PRODUCTS LIGHTING EQUIPMENT Floors . .66 X24 X-Effects Projector . .34 Floor Accessories . .70 Vortex 360 Dual Rotator . .35 Gobo Rotators . .36 Controllers . .37 TAPES . .71 Infinity . .38 I-Cue Intelligent Mirror . .39 DESIGNER PRODUCTS . .72 LitePad . .40 Power Supply Units . .41 INDEX . .76 PROJECTION EQUIPMENT THE ROSCO SALES TEAM . .78 iPro Image Projector . .42 LIGHTING DESIGN/CONTROL Keystroke . .44 SCREENS . .45 2 www.rosco.com SWATCHBOOKS Colour filter swatchbooks have been, for many years, the lighting designer’s favourite tool for colour filter selection. Available at Rosco dealers everywhere, the swatchbooks contain samples of every colour and its transmission chart. All Rosco swatchbooks are dated and users are advised to have an up-to-date swatchbook on hand. Contact Rosco or your nearest dealer for a free swatchbook. The Designer Colour Selector and Lightlab Editions will have a charge. Contact Rosco for pricing. Supergel No. 99101 Supergel Swatchbook No. 99018 Supergel Designer Colour Selector approximate size 7.5cm x 15.24cm cm. Roscolux No.9979 Roscolux Swatchbook No. 990109 Roscolux Designer Colour Selector approximate size 7.5cm x 15.24cm The E-Colour+ swatchbook now includes the 5000 series. -

The Royal Ballet Celebrates American Choreographers George Balanchine and Jerome Robbins

27 May 2021 #OurHouseToYourHouse Fundraising for our future The Royal Ballet celebrates American choreographers George Balanchine and Jerome Robbins The Royal Ballet celebrates the rich history of American ballet in classic works by George Balanchine and Jerome Robbins, two choreographic giants of the 20th century. Balanchine and Robbins open’s on 4 June and is live streamed on 11 June at 7.30pm priced £16. The programme includes two classic works by Balanchine; Apollo and Tchaikovsky Pas De Deux. Apollo was created for Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes in 1928 and is regarded as a masterpiece of neoclassicism in its striking depiction of the young god of music and his three muses. Set to music by Igor Stravinsky the ballet was last performed by The Company in 2014. In 1960 Balanchine created Tchaikovsky Pas de Deux for New York City Ballet. The ballet is a showcase of technical challenges and bravura and is set to a long-lost movement from Tchaikovsky’s original score for Swan Lake. Jerome Robbins played a crucial role in the development of American ballet as a contemporary of Balanchine and as an influential figure in Broadway. His 1969 ballet Dances at a Gathering is an ode to pure dance, set to music by Chopin. While plotless, the intimacy of the ballet creates a powerful sense of community which promises to resonate powerfully with audiences and dancers again following its revival in 2020 just before lockdown. This programme features a host of debuts by Royal Ballet Principals Fumi Kaneko, Yasmine Naghdi, Matthew Ball, Cesar Corrales and Vadim Muntagirov and First Soloists Claire Calvert, Melissa Hamilton, Mayara Magri, Anna Rose O’Sullivan and Reece Clarke The event will be broadcast live via the Royal Opera House website on Friday 11 June at 7.30pm, priced at £16.00 per household and will be available to watch on demand until 10 July.