May Be Xeroxed

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MREAC, 2010 & Overview of Past Three Years

MREAC, 2010 & Overview of Past Three Years Kara L. Baisley Freshwater Mussel Survey of the Miramichi River Watershed – MREAC, 2010 & Overview of Past Three Years Table of Contents List of Figures ................................................................................................................................................ ii List of Tables ................................................................................................................................................. ii Acknowledgements ...................................................................................................................................... iii 1.0. Introduction ...................................................................................................................................... 1 2.0. Methodology ..................................................................................................................................... 2 3.0. Results and Observations .................................................................................................................. 5 4.0. Discussion & Review ......................................................................................................................... 8 4.1. Eastern Pearlshell ( Margaritifera margaritifera ) ................................................................... 10 4.2. Eastern Elliptio ( Elliptio complanata ) ..................................................................................... 11 4.3. Eastern Floater (Pyganodon -

Application of the Canadian Aquatic Biomonitoring Network (CABIN)

Application of the Canadian Aquatic Biomonitoring Network (CABIN) The Miramichi River Environmental Assessment Committee Synopsis 2015 Application of the Canadian Aquatic Biomonitoring Network (CABIN) Synopsis 2015 Vladimir King Trajkovic Miramichi River Environmental Assessment Committee PO Box 85, 21 Cove Road Miramichi, New Brunswick E1V 3M2 Phone: (506) 778-8591 Fax: (506) 773-9755 Email: [email protected] Website: www.mreac.org March 8, 2016 ii Acknowledgements The Miramichi River Environmental Assessment Committee (MREAC) would like to thank Environment Canada (EC) for their support through the Atlantic Ecosystem Initiative for the Canadian Aquatic Biomonitoring Network (CABIN) project titled “The Atlantic Provinces Canadian Aquatic Biomonitoring Network (CABIN) Collaborative”. A special thank you is also extended to Lesley Carter and Vincent Mercier for their support and training during this endeavour. iii Table of Contents Page 1.0 Introduction ............................................................................................................................1 2.0 Background.............................................................................................................................2 3.0 Results ....................................................................................................................................6 4.0 Discussion.............................................................................................................................20 5.0 Conclusion ............................................................................................................................22 -

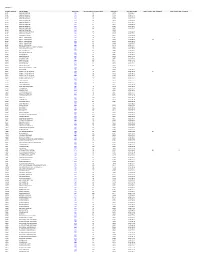

Bridge Condition Index

DISTRICT 2 BRIDGE NUMBER BRIDGE NAME MAP PAGE BRIDGE CONDITION INDEX (BCI) YEAR BUILT LAST INSPECTION POSTED LOAD LIMIT (TONNES) POSTED AXLE LIMIT (TONNES) B102 BARNABY RIVER #1 203 96 1974 2014-08-11 B105 BARNABY RIVER #2 219 98 1976 2014-07-15 B108 BARNABY RIVER #3 219 79 1966 2014-07-15 B111 BARNABY RIVER #4 219 90 1958 2014-07-17 B114 BARNABY RIVER #5 219 79 1954 2014-07-17 B120 BARNABY RIVER #7 234 77 1972 2015-08-19 B123 BARNABY RIVER #8 234 42 1925 2015-08-19 B126 BARNABY RIVER #9 234 75 1981 2015-08-19 B129 BARNABY RIVER #10 234 88 1965 2014-07-17 B133 BARNABY RIVER #12 234 2014 B138 BARTHOLEMEW RIVER #1 232 77 1978 2015-08-20 B141 BARTIBOG RIVER #1 190 75 1976 2015-07-15 B144 BARTIBOG RIVER #2 173 75 1950 2015-08-06 B204 BAY DU VIN RIVER #1 191 74 1982 2015-08-05 B207 BAY DU VIN RIVER #2 191 71 1967 2015-08-05 18 3 B210 BAY DU VIN RIVER #4 221 87 1992 2015-08-05 B213 BAY DU VIN RIVER #5 220 92 1968 2014-07-17 B216 BAY DU VIN RIVER #7 220 28 1971 2014-07-17 B282 BEAVERBROOK BLVD. NBECR OVERPASS 204 96 1981 2014-08-11 B438 BIG ESKEDELLOC RIVER 156 76 1984 2015-08-06 B456 BIG HOLE BROOK 263 90 1996 2015-08-20 B459 BIG MARSH BROOK #1 136 79 1989 2014-08-12 B489 BLACK BROOK 249 53 1971 2014-07-15 B501 BLACK BROOK #1 190 66 1966 2015-07-14 B534 BLACK RIVER #2 190 94 1976 2015-07-14 B543 BLACK RIVER #3 205 100 1977 2014-07-17 B564 BLACK RIVER #5 205 47 1961 2014-07-17 B630 BOGAN BROOK 277 41 1976 2014-07-14 B753 BRUCE BROOK #1 261 98 1993 2014-07-14 B760 BRYENTON-DERBY (RTE. -

Maritime Provinces Fishery Regulations Règlement De Pêche Des Provinces Maritimes TABLE of PROVISIONS TABLE ANALYTIQUE

CANADA CONSOLIDATION CODIFICATION Maritime Provinces Fishery Règlement de pêche des Regulations provinces maritimes SOR/93-55 DORS/93-55 Current to September 11, 2021 À jour au 11 septembre 2021 Last amended on May 14, 2021 Dernière modification le 14 mai 2021 Published by the Minister of Justice at the following address: Publié par le ministre de la Justice à l’adresse suivante : http://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca http://lois-laws.justice.gc.ca OFFICIAL STATUS CARACTÈRE OFFICIEL OF CONSOLIDATIONS DES CODIFICATIONS Subsections 31(1) and (3) of the Legislation Revision and Les paragraphes 31(1) et (3) de la Loi sur la révision et la Consolidation Act, in force on June 1, 2009, provide as codification des textes législatifs, en vigueur le 1er juin follows: 2009, prévoient ce qui suit : Published consolidation is evidence Codifications comme élément de preuve 31 (1) Every copy of a consolidated statute or consolidated 31 (1) Tout exemplaire d'une loi codifiée ou d'un règlement regulation published by the Minister under this Act in either codifié, publié par le ministre en vertu de la présente loi sur print or electronic form is evidence of that statute or regula- support papier ou sur support électronique, fait foi de cette tion and of its contents and every copy purporting to be pub- loi ou de ce règlement et de son contenu. Tout exemplaire lished by the Minister is deemed to be so published, unless donné comme publié par le ministre est réputé avoir été ainsi the contrary is shown. publié, sauf preuve contraire. ... [...] Inconsistencies in -

Social Studies Grade 3 Provincial Identity

Social Studies Grade 3 Curriculum - Provincial ldentity Implementation September 2011 New~Nouveauk Brunsw1c Acknowledgements The Departments of Education acknowledge the work of the social studies consultants and other educators who served on the regional social studies committee. New Brunswick Newfoundland and Labrador Barbara Hillman Darryl Fillier John Hildebrand Nova Scotia Prince Edward Island Mary Fedorchuk Bethany Doiron Bruce Fisher Laura Ann Noye Rick McDonald Jennifer Burke The Departments of Education also acknowledge the contribution of all the educators who served on provincial writing teams and curriculum committees, and who reviewed and/or piloted the curriculum. Table of Contents Introduction ........................................................................................................................................................ 1 Program Designs and Outcomes ..................................................................................................................... 3 Overview ................................................................................................................................................... 3 Essential Graduation Learnings .................................................................................................................... 4 General Curriculum Outcomes ..................................................................................................................... 6 Processes .................................................................................................................................................. -

Freshwater Mussel Survey for the Miramichi River Watershed

Freshwater Mussel Survey for the Miramichi River Watershed MREAC, 2008 Kara L. Baisley Freshwater Mussel Survey of the Miramichi River Watershed – MREAC, 2008 Table of Contents List of Figures ................................................................................................................................. ii List of Tables ................................................................................................................................... ii 1.0. Introduction .......................................................................................................................... 1 2.0. Methodology ........................................................................................................................ 2 3.0. Results and Observations ..................................................................................................... 5 4.0. Discussion ............................................................................................................................ 9 4.1. Eastern Pearlshell (Margaritifera margaritifera)............................................................... 9 4.2. Eastern Elliptio ( Elliptio complanata ) .............................................................................. 9 4.3. Eastern Floater ( Pyganodon cataracta ) .......................................................................... 10 5.0. Conclusion .......................................................................................................................... 11 6.0. References -

Striped Bass Culture in Eastern Canada

Fisheries and Oceans Pêches et Océans Canada Canada Canadian Stock Assessment Secretariat Secrétariat canadien pour l’évaluation des stocks Research Document 99/004 Document de recherche 99/004 Not to be cited without Ne pas citer sans permission of the authors1 autorisation des auteurs1 Striped bass culture in eastern Canada David Cairns Science Branch, Department of Fisheries and Oceans, Box 1236, Charlottetown PEI C1A 7M8 [email protected] Kim Robichaud-LeBlanc Science Branch, Department of Fisheries and Oceans, Halifax, NS B3J 2S7 [email protected] Rodney Bradford Science Branch, Department of Fisheries and Oceans, Halifax, NS B3J 2S7 [email protected] Richard H. Peterson Science Branch, Department of Fisheries and Oceans, St. Andrews, NB E0G 2X0 [email protected] Randy Angus Cardigan Fish Hatchery, AVC Inc., RR3 Cardigan PEI C0A 1G0 [email protected] 1 This series documents the scientific basis for 1 La présente série documente les bases the evaluation of fisheries resources in Canada. scientifiques des évaluations des ressources As such, it addresses the issues of the day in halieutiques du Canada. Elle traite des the time frames required and the documents it problèmes courants selon les échéanciers contains are not intended as definitive dictés. Les documents qu’elle contient ne statements on the subjects addressed but rather doivent pas être considérés comme des as progress reports on ongoing investigations. énoncés définitifs sur les sujets traités, mais plutôt comme des rapports d’étape sur les études en cours. Research documents are produced in the official Les documents de recherche sont publiés dans language in which they are provided to the la langue officielle utilisée dans le manuscrit Secretariat. -

Status of Striped Bass (Morone Saxatilis) in the Gulf of St

Not to be cited without permission of Ne pas citer sans autorisation des the authors ' auteurs' DFO Atlantic Fisheries MPO Pêches de l'Atlantique Research Document 95/119 Document de recherche 95/ 11 9 Status of Striped Bass (Morone saxatilis) in the Gulf of St. Lawrence by R.G. Bradford New Brunswick Wildlife Federation P.O. Box 20211, Frede ricton, N.B. E3B 7A2 G. Chaput' Department of Fisheries & Ocean s Science Branch, Gulf Région P.O . Box 503 0 Moncton, New Brunswick, E 1 C 9B6 and E. Tremblay Kouchibouguac National Park Kouchibouguac, N.B., EOA 2A0 'This series documents the scientific 'La présente série documente les bases basic for the evaluation of fisheries scientifiques des évaluations des resources in Atlantic Canada. As such, it ressources halieutiques sur la côte addresses the issues of the day in the Atlantique du Canada. Elle traite des time frames required and the documents problèmes courants selon les échéanciers it contains are not intended as definitive dictés. Les documents qu'elle contient ne statements on the subjects addressed but doivent pas être considérés comme des rather as progress reports on ongoing énoncés définitifs sur les sujets traités, investigations. mais plutôt comme des rapports d'étape sur les études en cours . Research documents are produced in the Les documents de recherche sont publiés official language in which they are dans la langue officielle utilisée dans le provided to the secretariat . manuscrit envoyé au secrétariat. TABLE OF CONTENT S ABSTRACT/RÉSUMÉ . 3 INTRODUCTION . 4 DESCRIPTION OF FISHERIES . 5 TARGET . 6 FISHERY DATA . .. 6 RESEARCH DATA . -

Fish Guide 2021

Fish 2021 A part of our heritage Did you know? • Your season Angling Licence is now valid from April 15th until March 31st of the following year. This means the upcoming winter fishing season from January 1st to March 31st is included in your licence. • You can keep track of your fishing trips and fish catches online. This information is kept confidential and is needed by fisheries managers to sustain quality fishing in New Brunswick. Unfortunately, fewer than 1% of anglers take the time to share their information. Please do your part by submitting the postage-paid survey card in the center of this book or by making your personal electronic logbook here: http://dnr-mrn.gnb.ca/AnglingRecord/?lang=e. • The Department of Natural Resources and Energy Development (DNRED) offers a variety of interactive maps to help anglers with fishing rules, lake depths and stocked waters. Check them out on our webpage under Interactive Maps at: https:// www2.gnb.ca/content/gnb/en/departments/erd/natural_resources/content/fish.html Fishing Survey (Online version) (Mail-in version) Interactive Maps Fishing Regulations (web) Fishing Regulations (mobile) Winter Fishing Regulations Stocked Waters Tidal Waters Lake Depths Photo Jeremy McLean – Tourism N.B. A message from the Minister of Natural Resources and Energy Development New Brunswickers have faced a number Fish NB Days are the perfect opportunity of challenges over the past year as a to introduce friends and family to rec- result of the COVID-19 global pandemic. reational fishing. Twice yearly, in early While fishing traditions have always run June and the Family Day long weekend deep in our province, they held special in February, residents and non-residents meaning this year. -

1996-97 BIO Biennial Review

Science Review 1996 & ’97 of the Bedford Institute of Oceanography Gulf Fisheries Centre Halifax Fisheries Research Laboratory St. Andrews Biological Station Published by: Department of Fisheries and Oceans Maritimes Region 2000 Table of Contents Introduction Cutting Edge Sonar Technologies Explored for Pelagic Stock Assessment Norm Cochrane Improving the Skill of Search-and-Rescue Forecasts Peter C. Smith, Donald J. Lawrence, Keith R. Thompson, Jinyu Sheng, Gilles Verner, Judy St. James, Natacha Bernier and Len Feldman Studies on the Impact of Mobile Fishing Gear on Benthic Habitat and Communities D.C. Gordon Jr., P. Schwinghamer, T.W. Rowell, J. Prena, K. Gilkinson, W.P. Vass, D. L. McKeown, C. Bourbonnais, K. MacIsaac Designing and Building a CHS Bathymetric Data Warehouse S. R. Forbes, R. G. Burke, H. Varma The World Ocean Circulation Experiment Observation Program Allyn Clarke, Fred Dobson, Ross Hendry, Anthony Isenor, Peter Jones, John Lazier, George Needler, Neil Oakey and Dan Wright The Emerging Role of Marine Geology in Benthic Ecology Gordon B. J. Fader, R.A. Pickrill, Brian J. Todd, Robert C. Courtney, D. Russell Parrott Northern Shrimp in Southern Waters - The Limits to the Fishery are Clearly Environmental Peter Koller Fate and Effects of Offshore Hydrocarbon Drilling Waste T. G. Milligan, D. C. Gordon, D. Belliveau, Y. Chen, P. J. Cranford, C. Hannah, J. Loader, D. K. Muschenheim Risk Assessment in Fisheries Management A. Sinclair, S. Gavaris, B. Mohn Shellfish Water Quality Protection Program Amar Menon Distribution and Abundance of Bacteria in the Ocean Bill Li, P. M. Dickie Ocean Forecast for the East Coast of Canada C. -

Annual Report 1961

240 - OrrA -* Lute, vEsz XIA 0E6 CANAD2t • ,•>t •••■ MTMIM1 DEPARTMENT OF FISHERIES CANADA Linn 4 240 0171 FLOOR OTTAWA, ONTARIO, WEST. K IA 0E6 CANADA Being the Ninety-fifth Annual Fisheries Report of the Government of Canada 61925-4---1 ROGER DUFIAMEL, F.R.S.C. QUEEN'S PRINTER AND CONTROLLER OF STATIONERY OTTAWA, DM Price: 50 cents Cat. No: Fa 1-1961 To His Excellency Major-General Georges P. Vanier, D.S.O., C.D., Governor General and Commander-in-Chief of Canada May it Please Your Excellency: I have the honour herewith, for the information of Your Excellency and the Parliament of Canada, to present the Annual Report of the Department of Fisheries for the year 1961, and the financial statements of the Department for the fiscal year 1961-1962 Respectfully submitted, Minister of Fisheries. 61925-4- Li- To the Honourable J. A.ngus MacLean, M.P., Minister of Fisheries, Ottawa, Canada. Sir: I submit herewith the Annual Report of the Department of Fisheries for the year 1961, and the financial statements of the Department for the fiscal year 1961-1962. I have the honour to be, Sir, Your obedient servant e,6) Deputy Minister. CONTENTS PAGE Introduction 7 Conservation and Development Service 9 Departmental Vessels 32 Inspection Service 35 Economics Service 43 Information and Consumer Service 49 Industrial Development Service 56 Fishermen's Indemnity Plan 61 Fisheries Prices Support Board 63 Fisheries Research Board of Canada 65 International Commissions 80 Special Committees 99 The Fishing Industry 102 Statistics of the Fisheries 107 APPENDICES 1. Financial Statements, 1961-1962 2. -

DFO Lil~Il ~ ~1L[1I11[1I1i1l111~1Lll1i[1Li $ Qu E 02011319

DFO lil~il ~ ~1l[1i11[1i1i1l111~1lll1i[1li $ qu e 02011319 CANADA FISH CULTURE DEVELOPMENT A Report of the Fish Culture Development Branch of the Conservation and Development Service SH 37 A11 Reprinted from the 'Twenty"Fifth Annual Report 1954 of the Department of Fisheries of Canada c. 2 RARE SH 37A11 1954 c.2 RARE Canada. Fish Culture Development Branch Fish culture development. a report of the J 02011319 c.2 SH 37 A11 1954 c.2 RARE d Fish Culture Development Branch Cana a. rt of the Fish culture development. a repo 02011319 c.2 I• FISH CULTURE DEVELO NDER the British North America Act, legislative jurisdiction in coastal U and inland fisheries was given to the Government of Canada. Since that time, however, as a result of various agreements, certain provinces have accepted in a greater or lesser degree the administration of the fisheries within their bound aries. Thus the Province of Quebec administers all its fisheries both freshwater and marine. The Provinces of Ontario, Manitoba, Saskatchewan and Alberta 1 assume responsibility for the freshwater species while the Government of Canada handles such marine problems as occur. In British Columbia and Newfoundland the Government of Canada is completely responsible for the marine and anadromous (salmon, smelts, etc.) fish while the provinces take charge of the purely freshwater species. In Prince Edward Island, Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, the Northwest Territories and the Yukon Territory, the Government of Canada carries out its full responsibility in exerting not only legislative but administrative control. It should be stressed that everywhere in Canada, fisheries legislation is federal even though certain provinces may assume enforcement responsibility.