Community Adaptation Strategies to Floods

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fact Sheet How Dams Work

Fact sheet How dams work December 2015 In South East Queensland, our drinking water is predominantly Flood mitigation sourced from dams, which collect run-off rainwater from our catchments and store it. Our dams provide a safe, secure and At its most basic level, flood mitigation is capturing water and cost-effective water supply, as well as help to mitigate floods. then releasing it at a slower rate, with the aim of minimising river levels downstream of the dam. When dams fill, they are designed to pass the excess water into the creek or river system they are built on. What is Full Supply Level? Dam release notification service The Full Supply Level of a dam is the approved water storage level of the dam for drinking and/or irrigation purposes. Seqwater offers a free dam release notification service, which provides subscribers with notifications when gated dams For un-gated dams, if inflows result in the water level rising release water or un-gated dams are spilling. above the Full Supply Level, the water will spill out of the dam. This spilling cannot be controlled. Subscribers to Seqwater’s dam release notification service will also be notified when higher outflows are occurring from For our gated dams (Wivenhoe, Somerset and North Pine), if a spilling dam due to high inflows resulting from rainfall in the inflows result in the water level rising above the Full Supply catchment. Level, Seqwater will make controlled releases for either flood mitigation or to protect the safety of the dam. These notifications advise caution downstream due to potential hazards to people and property. -

Where Water Comes From

Year 6 Lesson 1 Where water comes from www.logan.qld.gov.au Learning objectives Students will be able to determine: The definition of a catchment. Basic principles of catchment management. Issues associated with balancing the needs of various catchment users. Learning outcomes Subject Strand & Content Descriptors Science Science Understanding Sudden geological changes or extreme weather conditions can affect Earth's surface (ACSSU095) Science as a Human Endeavour Scientific knowledge is used to inform personal and community decisions (ACSHE220) Geography Geographical Knowledge & Understanding Places are connected to each other locally, regionally and globally, through the movement of goods, people and ideas as well as human or environmental events. Geographical Skills & Understanding Pose geographical questions that range in complexity and guide deep inquiry then speculate on their answers Identify a variety of information sources that will be used for inquiry, considering their validity Identify and create appropriate materials, geographical tools or equipment to collect data or observations, using formal measurements and digital and spatial technologies as appropriate Important questions What is a catchment? How do well-managed catchments contribute to clean water supplies? What impacts can industrial, agricultural or other users have on the dam catchment? What mechanisms are used to manage competing demands on catchments? P 1 of 3 DM 7962814 www.logan.qld.gov.au Background information – the dam and its catchment A catchment is an area of land, bordered by hills or mountains, from which runoff flows to a low point – either a dam or the mouth of the river. Water running from a bath down the plughole is a simple representation of a catchment. -

Fact Sheet Wivenhoe Dam

Fact sheet Wivenhoe Dam Wivenhoe Dam Wivenhoe Dam’s primary function is to provide a safe drinking Key facts water supply to the people of Brisbane and surrounding areas. It also provides flood mitigation. Name Wivenhoe Dam (Lake Wivenhoe) Watercourse Brisbane River The water from Lake Wivenhoe, the reservoir formed by the dam, is stored before being treated to produce drinking water Location Upstream of Fernvale and follows the water journey of source, store and supply. Catchment area 7020.0 square kilometres Length of dam wall 2300.0 metres Source Year completed 1984 Wivenhoe Dam is located on the Brisbane River in the Somerset Type of construction Zoned earth and rock fill Regional Council area. embankment Spillway gates 5 Water supply Full supply capacity 1,165,238 megalitres Wivenhoe Dam provides a safe drinking water supply for Flood mitigation 1,967,000 megalitres Brisbane, Ipswich, Logan, Gold Coast, Beaudesert, Esk, Gatton, Laidley, Kilcoy, Nanango and surrounding areas. The construction of the dam involved the placement of around 4 million cubic metres of earth and rock fill, and around 140,000 Wivenhoe Dam was designed and built as a multifunctional cubic metres of concrete in the spillway section. Excavation facility. The dam was built upstream of the Brisbane River, of 2 million cubic metres of earth and rock was necessary to 80 kilometres from Brisbane City. At full supply level, the dam construct the spillway. holds approximately 2,000 times the daily water consumption needed for Brisbane. The Brisbane Valley Highway was relocated to pass over the dam wall, while 65 kilometres of roads and a number of new Wivenhoe Dam, along with the Somerset, Hinze and North Pine bridges were required following construction of the dam. -

Somerset and Wivenhoe Dam Safety Upgrades – Business

Somerset and Wivenhoe Dam Safety Upgrades – Business Case Stage APRIL 2019 Somerset Dam was built between 1937 and 1959. Wivenhoe Dam was completed in 1985. Both dams were designed to the engineering standards of their time. We now know more about the risks of extreme floods to the Somerset and Wivenhoe Dam walls. Both dams will be upgraded so that they can withstand much larger floods. What has changed since the dams were built? Some things have changed since the dams were built or last upgraded. These include: • significant population growth downstream • advances in dam design and the development of consistent risk assessment methods • improved estimates of extreme rainfall events • data from recent floods and updated flood modelling. An independent assessment has found the dams do not meet modern Queensland Government dam safety guidelines. We now know extreme floods could exceed the design capacity of the dams. Under the Water Supply (Safety and Reliability) Act 2008, we need to upgrade both dams to meet the guidelines. Lowering water levels in Somerset and Wivenhoe In January 2016, Seqwater changed the way it manages both Somerset and Wivenhoe Dams. These changes immediately improved the ability of both dams to withstand extreme floods and maintain flood mitigation. Changes include: • Changing the flood operations manual for both dams • Lowering the water supply storage volume of Somerset Dam to 80% of its normal volume • Lowering the water supply storage volume of Wivenhoe Dam to 90% of its normal volume. Lowering the water supply storage volume increased the flood storage volume in the dams. What to expect Get involved The water supply storage levels in both dams will remain Identifying the social, environmental and heritage impacts lowered during the design and construction of the of the shortlisted upgrade options for Somerset Dam is part Somerset Dam safety upgrade. -

Purified Recycled Water in the Lockyer Valley

Fact Sheet December 2012 Purified Recycled Water in the Lockyer Valley The water supply security of South East Queensland (SEQ) has recently been increased by the construction of the Western Corridor Recycled Water Scheme. The infrastructure of advanced wastewater treatment plants provides purified recycled water (PRW) to the SEQ Water Grid for indirect potable reuse of effluent from urban areas. With a maximum combined production capacity of 232 million litres of PRW a day, it is the third largest recycled water scheme in the world and the largest in the southern hemisphere. This additional water supply is critical during drought conditions but is underused in wet periods. The provision of recycled water in an environmentally Background sound and socially-equitable manner requires measured The Urban Water Security Research Alliance (the Alliance) understanding of the potential impacts on the region’s worked closely with the Queensland Water Commission, soils, groundwater system, environment (such as salinity the former Queensland Department of Environment and issues) and the economy. Therefore, a holistic framework Resource Management, WaterSecure (now Seqwater) and was required to inform an integrated water management the SEQ Water Grid Manager, as well as irrigators and the plan involving the use of PRW. This was achieved through farming community. a multi-tiered assessment incorporating environmental risk analysis, climate modelling, regulatory considerations and Together we explored the feasibility of providing agro-economics. approximately 20 million litres per year of PRW to supplement irrigation supplies in the Lockyer Valley, 80 km The environmental risks and benefits from the supply of PRW west of Brisbane. were the core subjects addressed by this research, using a combination of field research, water quality and quantity Alliance research explored whether the use of PRW can serve modelling , and unstructured stakeholder interviews. -

Manual of Operational Procedures for Flood Mitigation at Wivenhoe Dam and Somerset Dam 1 the Controlled Version of This Document Is Registered

Wivenhoe Dam and Somerset Dam Manual of Operational Procedures for Flood Mitigation Revision 15 | November 2019 15 Revision No. Date Amendment Details 0 27 October 1968 Original issue. 1 6 October 1992 Complete revision and re-issue. 2 13 November 1997 Complete revision and re-issue. 3 24 August 1998 Change to page 23. 4 6 September 2002 Complete revision and re-issue. 5 4 October 2004 Complete revision. 6 20 December 2004 Miscellaneous amendments and re-issue. 7 November 2009 (approved by Gazette notice Complete revision. 22 January 2010) 8 September 2011 Revision but no substantive alteration of objectives, strategies or operating practices. 9 November 2011 Insertion of Section 8 and consequential amendments. 10 October 2012 Revision but no substantive alteration of objectives, strategies or operating practices. 11 November 2013 Revision to take account of changes to the Act and improve clarity, but no substantive alteration of objectives or strategies. Operating practices amended to exclude consideration of Twin Bridges and Savages Crossing following stakeholder input. 12 November 2014 Significant revision including changes from WSDOS investigations, legislative changes and a number of general improvements. 13 November 2015 A number of minor updates to improve readability and application. 14 November 2016 Changes to account for the revised Maximum Flood Storage Level for Somerset Dam and a number of general improvements. 15 November 2019 Revision Revision No: 15 – November 2019 Seqwater Doc No: MAN-0051 Manual of Operational Procedures for Flood Mitigation at Wivenhoe Dam and Somerset Dam 1 The controlled version of this document is registered. All other versions including printed versions are uncontrolled. -

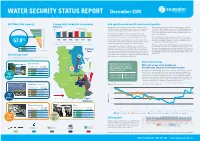

WATER SECURITY STATUS REPORT December 2020

WATER SECURITY STATUS REPORT December 2020 SEQ Water Grid capacity Average daily residential consumption Grid operations and overall water security position (L/Person) Despite receiving rainfall in parts of the northern and southern areas The Southern Regional Water Pipeline is still operating in a northerly 100% 250 2019 December average of South East Queensland (SEQ), the region continues to be in Drought direction. The Northern Pipeline Interconnectors (NPI 1 and 2) have been 90% 200 Response conditions with combined Water Grid storages at 57.8%. operating in a bidirectional mode, with NPI 1 flowing north while NPI 80% 150 2 flows south. The grid flow operations help to distribute water in SEQ Wivenhoe Dam remains below 50% capacity for the seventh 70% 100 where it is needed most. SEQ Drought Readiness 50 consecutive month. There was minimal rainfall in the catchment 60% average Drought Response 0 surrounding Lake Wivenhoe, our largest drinking water storage. The average residential water usage remains high at 172 litres per 50% person, per day (LPD). While this is less than the same period last year 40% 172 184 165 196 177 164 Although the December rain provided welcome relief for many of the (195 LPD), it is still 22 litres above the recommended 150 LPD average % region’s off-grid communities, Boonah-Kalbar and Dayboro are still under 57.8 30% *Data range is 03/12/2020 to 30/12/2020 and 05/12/2019 to 01/01/2020 according to the SEQ Drought Response Plan. drought response monitoring (see below for additional details). 20% See map below and legend at the bottom of the page for water service provider information The Bureau of Meteorology (BOM) outlook for January to March is likely 10% The Gold Coast Desalination Plant (GCDP) had been maximising to be wetter than average for much of Australia, particularly in the east. -

Somerset Dam

ENGINEERS AUSTRALIA ENGINEERING HERITAGE AUSTRALIA HERITAGE RECOGNITION PROGRAM Nomination Document for THE SOMERSET DAM BCC Image BCC-C54-16 Somerset Region South-east Queensland January 2010 Table of Contents Nomination Form .................................................................................................................................. 1 Introduction........................................................................................................................................... 2 Letter of support: ................................................................................................................................... 3 Location Maps ........................................................................................................................................ 4 Heritage Assessment 1. BASIC DATA ..................................................................................................................................... 5 2. ASSESSMENT OF SIGNIFICANCE Statement of Significance:.............................................................................................................. 6 Proposed wording for interpretation panel .......................................................................................... 9 Appendix A: Paper by Geoffrey Cossins............................................................................................... 10 References ................................................................................................................................. -

Splityard Creek Dam

EMERGENCY ACTION PLAN – SPLITYARD CREEK DAM ISSUE: 13 Date: February 2020 Prepared by CS Energy/GHD Limited 1 Controlled Copy No: Gated: No Manned: Yes 2 Type: Earth and rock-fill embankment Project: Splityard Creek Dam EAP File no.: F/19/1991 Rural no.: 683 Wivenhoe Somerset Road (Power Station) o Location: Lat. -27.371944 (27°22'19"S) o Lon. 152.640833 (152°38'27"E) DISCLAIMER: This report has been produced by CleanCo to provide information for client use only. The information contained in this report is limited by the scope and the purpose of the study and should not be regarded as completely exhaustive. This report contains confidential information or information which may be commercially sensitive. If you wish to disclose this report to a third party, rely on any part of this report, use or quote information from this report in studies external to the Corporation, permission must first be obtained from the Chief Executive, CleanCo. 1 SunWater template 2 Monday to Friday Splityard Creek Dam - 2019/20 - i13 Emergency activation quick reference – Dam hazards The Emergency Action Plan (EAP) for Splityard Creek Dam covers three emergency conditions evaluated within CleanCo’s Dam Safety Management Program. Use Table 1 to select the relevant section of the EAP that deals with the emergency condition. Note: The Incident Coordinator (IC) is responsible for activating the EAP unless otherwise directed by the Dam Safety Technical Decision Maker (DSTDM). Should the IC be unavailable, the Dam Duty Officer (DDO) is responsible. Table 1: Emergency activation quick reference – Dam hazards Dam hazards and Activation levels for dam hazards section numbers Alert Lean Forward Stand Up Stand Down Piping: embankment, • Increasing leakage through dam • Increasing leakage through an 1. -

Water Secure Annual Report 2011 Layout Final.Indd

2010-11 annual report 6 October 2011 The Honourable Stephen Robertson MP Minister for Energy and Water Utilities PO Box 15216 City East Qld 4002 The Honourable Rachel Nolan MP Minister for Finance, Natural Resources and the Arts GPO Box 611 Brisbane Qld 4001 Dear Ministers I am pleased to present the Annual Report 2010-2011 for WaterSecure. I certify that this annual report complies with: • the prescribed requirements of the Financial Accountability Act 2009 and the Financial and Performance Management Standard 2009; • the detailed requirements set out in the Annual Reporting Guidelines for Queensland Government Agencies; and • the annual report requirements as set out in the Corporate Governance Guidelines for State Water Authorities. A checklist outlining the annual reporting requirements can be accessed on the WaterSecure website. Yours sincerely Sam Romano Acting Chief Executive Officer WaterSecure ContentsContents AboutAbout WaterSecureWaterSec Legislativegislative basiss 4 Rolee andand functionsf 4 Our vision 4 Our mission 4 Our values 4 Strategic choices and key priorities 5 Aligning WaterSecure’s objectives and strategies with the Toward Q2 Ambitions 5 CEO and Chair Report 6 Organisational Structure 7 Our Board 7 Our Executive Management Team 8 Our performance – what we delivered 10 Key Objectives 2010-2011 10 2010-2011 Highlights 11 Cumulative water supplied in 2010-2011 12 Key performance areas 13 Strategic Asset Management Plan 14 Environment 14 Water quality plans 14 Community 15 Industry and research 16 Our People 17 Corporate Governance 20 Summary of Financial Position and Performance Statement of Comprehensive Income 25 Statement of Financial Position 26 Statement of Cash Flows 27 Financial Report 29 Glossary 78 How to comment on this annual report We value your comments on our annual report and any other matters relating to WaterSecure. -

Drinking Water Quality Management Plan Lakes Wivenhoe and Somerset, Mid-Brisbane River and Catchments

Drinking Water Quality Management Plan Lakes Wivenhoe and Somerset, Mid-Brisbane River and Catchments April 2010 Peter Schneider, Mike Taylor, Marcus Mulholland and James Howey Acknowledgements Development of this plan benefited from guidance by the Queensland Water Commission Expert Advisory Panel (for issues associated with purified recycled water), Heather Uwins, Peter Artemieff, Anne Woolley and Lynne Dixon (Queensland Department of Environment and Resource Management), Nicole Davis and Rose Crossin (SEQ Water Grid Manager) and Annalie Roux (WaterSecure). The authors thank the following Seqwater staff for their contributions to this plan: Michael Bartkow, Jonathon Burcher, Daniel Healy, Arran Canning and Peter McKinnon. The authors also thank Seqwater staff who contributed to the supporting documentation to this plan. April 2010 Q-Pulse Database Reference: PLN-00021 DRiNkiNg WateR QuALiTy MANAgeMeNT PLAN Executive Summary Obligations and Objectives 8. Contribute to safe recreational opportunities for SEQ communities; The Wivenhoe Drinking Water Quality Management Plan (WDWQMP) provides a framework to 9. Develop effective communication, sustainably manage the water quality of Lakes documentation and reporting mechanisms; Wivenhoe and Somerset, Mid-Brisbane River and and catchments (the Wivenhoe system). Seqwater has 10. Remain abreast of relevant national and an obligation to manage water quality under the international trends in public health and Queensland Water Supply (Safety and Reliability) water management policies, and be actively Act 2008. All bulk water supply and treatment involved in their development. services have been amalgamated under Seqwater as part of the recent institutional reforms for water To ensure continual improvement and compliance supply infrastructure and management in South with the Water Supply (Safety and Reliability) East Queensland (SEQ). -

An Economic Assessment of the Value of Recreational Angling at Queensland Dams Involved in the Stocked Impoundment Permit Scheme

An economic assessment of the value of recreational angling at Queensland dams involved in the Stocked Impoundment Permit Scheme Daniel Gregg and John Rolfe Value of recreational angling in the Queensland SIP scheme Publication Date: 2013 Produced by: Environmental Economics Programme Centre for Environmental Management Location: CQUniversity Australia Bruce Highway North Rockhampton 4702 Contact Details: Professor John Rolfe +61 7 49232 2132 [email protected] www.cem.cqu.edu.au 1 Value of recreational angling in the Queensland SIP scheme Executive Summary Recreational fishing at Stocked Impoundment Permit (SIP) dams in Queensland generates economic impacts on regional economies and provides direct recreation benefits to users. As these benefits are not directly traded in markets, specialist non-market valuation techniques such as the Travel Cost Method are required to estimate values. Data for this study has been collected in two ways in 2012 and early 2013. First, an onsite survey has been conducted at six dams in Queensland, with 804 anglers interviewed in total on their trip and fishing experiences. Second, an online survey has been offered to all anglers purchasing a SIP licence, with 219 responses being collected. The data identifies that there are substantial visit rates across a number of dams in Queensland. For the 31 dams where data was available for this study, recreational anglers purchasing SIP licences have spent an estimated 272,305 days fishing at the dams, spending an average 2.43 days per trip on 2.15 trips per year to spend 4.36 days fishing per angler group. Within those dams there is substantial variation in total fishing effort, with Somerset, Tinaroo, Wivenhoe and North Pine Dam generating more than 20,000 visits per annum.