Prospero's Girls

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Entertainment Business Supplemental Information Three Months Ended September 30, 2015

Entertainment Business Supplemental Information Three months ended September 30, 2015 October 29, 2015 Sony Corporation Pictures Segment 1 ■ Pictures Segment Aggregated U.S. Dollar Information 1 ■ Motion Pictures 1 - Motion Pictures Box Office for films released in North America - Select films to be released in the U.S. - Top 10 DVD and Blu-rayTM titles released - Select DVD and Blu-rayTM titles to be released ■ Television Productions 3 - Television Series with an original broadcast on a U.S. network - Television Series with a new season to premiere on a U.S. network - Select Television Series in U.S. off-network syndication - Television Series with an original broadcast on a non-U.S. network ■ Media Networks 5 - Television and Digital Channels Music Segment 7 ■ Recorded Music 7 - Top 10 best-selling recorded music releases - Upcoming releases ■ Music Publishing 7 - Number of songs in the music publishing catalog owned and administered as of March 31, 2015 Cautionary Statement Statements made in this supplemental information with respect to Sony’s current plans, estimates, strategies and beliefs and other statements that are not historical facts are forward-looking statements. Forward-looking statements include, but are not limited to, those statements using such words as “may,” “will,” “should,” “plan,” “expect,” “anticipate,” “estimate” and similar words, although some forward- looking statements are expressed differently. Sony cautions investors that a number of important risks and uncertainties could cause actual results to differ materially from those discussed in the forward-looking statements, and therefore investors should not place undue reliance on them. Investors also should not rely on any obligation of Sony to update or revise any forward-looking statements, whether as a result of new information, future events or otherwise. -

Resurrecting Ophelia: Rewriting Hamlet for Young Adult Literature

Corso di Laurea magistrale (ordinamento ex D.M. 270/2004) in Lingue e Letterature Europee, Americane e Postcoloniali Tesi di Laurea Resurrecting Ophelia: rewriting Hamlet for Young Adult Literature Relatore Ch. Prof. Laura Tosi Correlatore Ch. Prof. Shaul Bassi Laureando Miriam Franzini Matricola 840161 Anno Accademico 2013 / 2014 Index Introduction ................................................................................................................................................ i 1 Shakespeare adaptation and appropriation for Young People .................................. 1 1.1 Adaptation: a definition ............................................................................................................... 1 1.2 Appropriation: a definition ......................................................................................................... 6 1.3 Shakespop adaptations and the game of success............................................................... 9 1.4 Children’s Literature: a brief introduction ........................................................................ 15 1.5 Adapting Shakespeare for kids: YA Literature ................................................................. 19 2 Ophelia: telling her story ............................................................................................................. 23 2.1 The Shakespearian Ophelia: a portrait ............................................................................... 23 2.2 Attempts of rewriting Hamlet in prose for children: the -

The Representation, Interpretation and Staging of Magic in Renaissance Plays from the Sixteenth Century Onwards

Ghent University Faculty of Arts and Philosophy The representation, interpretation and staging of magic in Renaissance plays from the sixteenth century onwards. A case study of William Shakespeare’s The Tempest, Macbeth and Cristopher Marlowe’s Doctor Faustus. Supervisor: Paper submitted in partial Professor Doctor fulfilment of the requirements for Sandro Jung the degree of “Master in de Taal- en Letterkunde: English-Spanish” by Tine Dekeyser August 2014 Word count: 27334 Dekeyser i Acknowledgments First of all, I would like to thank my supervisor, Professor Doctor Sandro Jung, for granting me the opportunity to continue working on the same topic of my BA-dissertation and for guiding me towards a more profound investigation of magic and the Renaissance society. Also, I want to thank Professor Jung for reading the many versions of this dissertation and for providing a lot of helpful suggestions throughout the year. Secondly, I would like to thank The British Museum for giving me permission to use their highly detailed engravings, without which this dissertation would not exist. Thirdly, I would like to thank my boyfriend and my mother for supporting me, listening to my dilemmas and calming me down when stress got the better of me. Also, I want to thank my boyfriend for helping me track down the movies I needed for my analyses. Dekeyser ii Table of Contents Acknowledgments ....................................................................................................................... i List of Illustrations ................................................................................................................... -

Southwest Digest (2009-2010)

Texas rcch l'm\cr-ity South".:st Collection 1'.0 Box41Q.ll lubbocl., Texas 7~409-1 Q.ll Bozeman Elementary Students Talk 'Red Raider Power'! Stllcl• ntl "' Bo:emtJn lltmtnlttry· Schooll\1'r<' tNafn/lo tl"' WI pep rail) ern ~qtmr~r 9 c nr M• & Mr> (i B Johmoa of Poll of Sbal101>atcr Jtm Jilhn pltltMrlha Rmdc~/'., rl!nnr.gcomf"'tlt""ln/bJ(htTo<BT. "'Churlcotd. Th.- \fmr{ar ..c, <;ballol\ator c<lcbu!QI lhetr >OD ((.'bn"mc), Ju!Jc Uflg nnd '"'"'' Dil, ~uta" upporlllmtrfor tud niJ l<>ltam abo1111h lq;u•pen~nu f<mng 10 1>11 T"'u 6Sth \\cd.loog '""" <r><&ry \\1lh 3 (oiQnJ D.mford, oil of I uhbock.. ft't.·lt ~ultural l>aen11l Rc-pn·u•ntatn-e.ltllf1((c r .fiuucn 1111J J,, u.~k111g 'lU(~flOttf Q) Tt-dt tude'.nt R~nac; rctc1phc.10 .tt the M.1X81t TreJn Jc.1hn~o.un and lhe (onncr Auu.bc: naunt,•f '" the pltoru tJIIlKhl, BQ~f'"UI" ,~,,,,f ;:radt r {)'JIUJ.H' Rahl(l 'M1 \lwlw.\ lum.l• ,, Hh font rn ,, Supcr Cemer SJturd.e) St-ptcm• F rccnun mJm~d Sc:pt I,., I Q44. ma_\; nt Rauk; ReJ b<r 12th '" \1.uhn Tbey M\'C se,en fbm dlildtcn WJd ape-cui fam gr;mdch1 dm..l4 JWII pand- oly fncnd. \\:and.~ Youngoff..ub. chtldn:n and oue gr-c:~-grnt- 100 BJack Men of West Texas Receives the 2009 bod. booted the celebration grandchild .. Robert Duncan Community Champion Award" lloey on: 1he porent of :.t.• ol' Un s:-nwddy,,\u ·u~t2J 20()9 IOQ IJia<l Men of \\e>t T<. -

![8]Sxatrc <Xstpbc CP[Zb](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2538/8-sxatrc-xstpbc-cp-zb-342538.webp)

8]Sxatrc <Xstpbc CP[Zb

M V C708F0AA8>A)BVgi^VaVgi^hiIdcn?VVh]VgZh]^hldg`djihZXgZihq8]bXST LIPOSUCTION LIPOSUCTION Unwanted Fat Removed Permanently! www.vitasurgical.com 202.452.1332202..452..1332 24 th and I St. Foggy Bottom Metro 7 703.533.102503..533..1025 Tyson’s Corner SUMMER 703.465.0666703..465..0666 Alexandria SPECIAL 301.738.6766301..738..6766 Bethesda ENDS 4 410.730.722610..730..7226 Columbia/ SOON! Baltimore :IN;EB<:MBHGH? u EBO>:EE=:R:MPPP'K>:=>QIK>LL'<HFu L>IM>F;>K.%+))/u --5A44++ Mn^l]Zr 8]SXaTRc <XSTPbc CP[ZbBTc ,%30%22%!58!0 N'G'mhf^]bZm^g^`hmbZmbhgl #ANADIANTROOPSREACTTOACOMRADESDEATH _hkk^e^Zl^h_BlkZ^eblhe]b^kl 5aXT]S[h5XaT)J#H#hig^`Z`^aah 983307B0D380A0180kN'G'\ab^_Dh_b:ggZg C6IDhdaY^Zg^c6[\]Vc^hiVcq( lZb]Fhg]Zra^phne]ZiihbgmZf^]bZmhk_hk bg]bk^\mmZedl[^mp^^gBlkZ^eZg]A^s[heeZa hgma^k^e^Zl^h_mphZ[]n\m^]BlkZ^eblhe& 0dcXb\;X]Z)G^h`g^hZhVh ]b^kl%ma^_bklmin[eb\phk]h_g^`hmbZmbhgl [^mp^^gma^[bmm^k^g^fb^llbg\^_b`ambg`bg " [Vi]Zgh\ZidaYZg!hijYn[^cYhq E^[Zghg^g]^]' Ma^Zgghng\^f^gmkZbl^]ma^ihllb[be& =Tfbf^acWh) bmrh_Zikblhg^klpZimh pbgma^lhe]b^klÍk^e^Zl^% 87HÉ]deZhg^YZ Zg^q\aZg`^maZmBlkZ^e dc8djg^XÉhYZWji aZlk^i^Zm^]erk^c^\m^]% Zme^Zlmbgin[eb\'Ngmbe $ ^cVcX]dgX]V^gq ghp%BlkZ^eaZ]bglblm^] maZmbmphne]ghmaZo^Zgr 4=C4AC08=<4=C \hgmZ\mpbmaA^s[heeZa% !NNAN [nmbml`ho^kgf^gmaZl [^^gng]^kbg\k^Zlbg`]hf^lmb\ik^llnk^ 3X\X]XbWTS mh[kbg`ma^mphahf^' ATcda]) Ma^Z`k^^f^gmhgma^f^]bZmbhg^__hkm \hne]fZkdZ[k^Zdmakhn`ahgZgblln^maZmbl 7\f]g7cfbY``Èg \kn\bZemhik^l^kobg`ma^_kZ`be^mak^^&p^^d& 6jY^dhaVkZ he]\^Zl^&_bk^maZm^g]^],-]Zrlh_BlkZ^e& [V^ahidhVi^h[n A^s[heeZa_b`ambg`'BlkZ^efhngm^]bmlh__^g& -

Theaters 3 & 4 the Grand Lodge on Peak 7

The Grand Lodge on Peak 7 Theaters 3 & 4 NOTE: 3D option is only available in theater 3 Note: Theater reservations are for 2 hours 45 minutes. Movie durations highlighted in Orange are 2 hours 20 minutes or more. Note: Movies with durations highlighted in red are only viewable during the 9PM start time, due to their excess length Title: Genre: Rating: Lead Actor: Director: Year: Type: Duration: (Mins.) The Avengers: Age of Ultron 3D Action PG-13 Robert Downey Jr. Joss Whedon 2015 3D 141 Born to be Wild 3D Family G Morgan Freeman David Lickley 2011 3D 40 Captain America : The Winter Soldier 3D Action PG-13 Chris Evans Anthony Russo/ Jay Russo 2014 3D 136 The Chronicles of Narnia: The Voyage of the Dawn Treader 3D Adventure PG Georgie Henley Michael Apted 2010 3D 113 Cirque Du Soleil: Worlds Away 3D Fantasy PG Erica Linz Andrew Adamson 2012 3D 91 Cloudy with a Chance of Meatballs 2 3D Animation PG Ana Faris Cody Cameron 2013 3D 95 Despicable Me 3D Animation PG Steve Carell Pierre Coffin 2010 3D 95 Despicable Me 2 3D Animation PG Steve Carell Pierre Coffin 2013 3D 98 Finding Nemo 3D Animation G Ellen DeGeneres Andrew Stanton 2003 3D 100 Gravity 3D Drama PG-13 Sandra Bullock Alfonso Cuaron 2013 3D 91 Hercules 3D Action PG-13 Dwayne Johnson Brett Ratner 2014 3D 97 Hotel Transylvania Animation PG Adam Sandler Genndy Tartakovsky 2012 3D 91 Ice Age: Continetal Drift 3D Animation PG Ray Romano Steve Martino 2012 3D 88 I, Frankenstein 3D Action PG-13 Aaron Eckhart Stuart Beattie 2014 3D 92 Imax Under the Sea 3D Documentary G Jim Carrey Howard Hall -

Shavian Shakespeare: Shaw's Use and Transformation of Shakespearean Materials in His Dramas

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1971 Shavian Shakespeare: Shaw's Use and Transformation of Shakespearean Materials in His Dramas. Lise Brandt Pedersen Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Pedersen, Lise Brandt, "Shavian Shakespeare: Shaw's Use and Transformation of Shakespearean Materials in His Dramas." (1971). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 2159. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/2159 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. I I 72- 17,797 PEDERSEN, Lise Brandt, 1926- SHAVIAN .SHAKESPEARE:' SHAW'S USE AND TRANSFORMATION OF SHAKESPEAREAN MATERIALS IN HIS DRAMAS. The Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, Ph.D., 1971 Language and Literature, modern University Microfilms, XEROXA Company, Ann Arbor, Michigan tT,TITn ^TnoT.r.a.A'TTAItf U4C PPPM MT PROPTT.MF'n FVAOTT.V AR RECEI VE D SHAVIAN SHAKESPEARE: SHAW'S USE AND TRANSFORMATION OF SHAKESPEAREAN MATERIALS IN HIS DRAMAS A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of English by Lise Brandt Pedersen B.A., Tulane University, 1952 M.A., Louisiana State University, 1963 December, 1971 ACKNOWLEDGMENT I wish to thank Dr. -

Cineplex Store

Creative & Production Services, 100 Yonge St., 5th Floor, Toronto ON, M5C 2W1 File: AD Advice+ E 8x10.5 0920 Publication: Cineplex Mag Trim: 8” x 10.5” Deadline: September 2020 Bleed: 0.125” Safety: 7.5” x 10” Colours: CMYK In Market: September 2020 Notes: Designer: KB A simple conversation plus a tailored plan. Introducing Advice+ is an easier way to create a plan together that keeps you heading in the right direction. Talk to an Advisor about Advice+ today, only from Scotiabank. ® Registered trademark of The Bank of Nova Scotia. AD Advice+ E 8x10.5 0920.indd 1 2020-09-17 12:48 PM HOLIDAY 2020 CONTENTS VOLUME 21 #5 ↑ 2021 Movie Preview’s Ghostbusters: Afterlife COVER STORY 16 20 26 31 PLUS HOLIDAY SPECIAL GUY ALL THE 2021 MOVIE GIFT GUIDE We catch up with KING’S MEN PREVIEW Stressed about Canada’s most Writer-director Bring on 2021! It’s going 04 EDITOR’S Holiday gift-giving? lovable action star Matthew Vaughn and to be an epic year of NOTE Relax, whether you’re Ryan Reynolds to find star Ralph Fiennes moviegoing jam-packed shopping online or out how he’s spending tell us about making with 2020 holdovers 06 CLICK! in stores we’ve got his downtime. Hint: their action-packed and exciting new titles. you covered with an It includes spreading spy pic The King’s Man, Here we put the spotlight 12 SPOTLIGHT awesome collection of goodwill and talking a more dramatic on must-see pics like CANADA last-minute presents about next year’s prequel to the super- Top Gun: Maverick, sure to please action-comedy Free Guy fun Kingsman films F9, Black Widow -

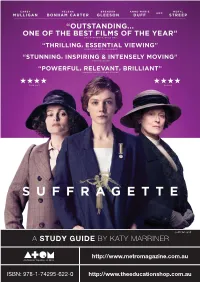

Suffragette Study Guide

© ATOM 2015 A STUDY GUIDE BY KATY MARRINER http://www.metromagazine.com.au ISBN: 978-1-74295-622-0 http://www.theeducationshop.com.au Running time: 106 minutes » SUFFRAGETTE Suffragette (2015) is a feature film directed by Sarah Gavron. The film provides a fictional account of a group of East London women who realised that polite, law-abiding protests were not going to get them very far in the battle for voting rights in early 20th century Britain. click on arrow hyperlink CONTENTS click on arrow hyperlink click on arrow hyperlink 3 CURRICULUM LINKS 19 8. Never surrender click on arrow hyperlink 3 STORY 20 9. Dreams 6 THE SUFFRAGETTE MOVEMENT 21 EXTENDED RESPONSE TOPICS 8 CHARACTERS 21 The Australian Suffragette Movement 10 ANALYSING KEY SEQUENCES 23 Gender justice 10 1. Votes for women 23 Inspiring women 11 2. Under surveillance 23 Social change SCREEN EDUCATION © ATOM 2015 © ATOM SCREEN EDUCATION 12 3. Giving testimony 23 Suffragette online 14 4. They lied to us 24 ABOUT THE FILMMAKERS 15 5. Mrs Pankhurst 25 APPENDIX 1 17 6. ‘I am a suffragette after all.’ 26 APPENDIX 2 18 7. Nothing left to lose 2 » CURRICULUM LINKS Suffragette is suitable viewing for students in Years 9 – 12. The film can be used as a resource in English, Civics and Citizenship, History, Media, Politics and Sociology. Links can also be made to the Australian Curriculum general capabilities: Literacy, Critical and Creative Thinking, Personal and Social Capability and Ethical Understanding. Teachers should consult the Australian Curriculum online at http://www.australiancurriculum.edu.au/ and curriculum outlines relevant to these studies in their state or territory. -

The Selected Writings of Leigh Hunt

The Selected Writings of Leigh Hunt Volume 6 Poetical Works, 1822-59 Edited by John Strachan LONDON PICKERING AND CHATTO 2003 CONTENTS Abbreviations ix Biographical Directory xi From The Liberal (1822) 'The Dogs. To the Abusers of The Liberal' 1 From The Liberal (1823) 'To a Spider running across a Room' 17 'Talari Innamorati' 19 'The Choice' 22 'Mahmoud' 32 Ultra-Crepidarius: A Satire on William Gifford (1823) 35 From The Examiner (1825) 'Vellutti to his Revilers' 47 From The New Monthly Magazine (1825) 'Caractacus' 57 From The Companion (1828) 'The Royal Line' 61 From The Tatler (1830) 'High and Low; or, How to Write History. Suggested by an article in a review from the pen of Sir Walter Scott, in which accounts are given of Massaniello and the Duke of Guise' 63 'Alter et Idem. A Chemico-Poetical Thought' 66 From The Tatler (1831) 'Le Brun' 69 'Expostulation and Candour' ' 70 'Lines Written on a Sudden Arrival of Fine Weather in May' 71 Selected Writings of Leigh Hunt, Volume 6 From The Athen&um (1832) 'The Lover of Music to the Pianoforte' 73 From The Poetical Works of Leigh Hunt (1832) 'Preface' 75 i From Leigh Hunt's London Journal (1834) 'Paganini. A Fragment5 99 'Thoughts in Bed Upon Waking and Rising. An "Indicator" in Verse' 102 'A Night Rain in Summer. June 28, 1834' 108 'An Angel in the House' 109 Captain Sword and Captain Pen. A Poem (1835) 111 From The New Monthly Magazine (1836) 'Songs and Chorus of the Flowers' 143 'The Glove and the Lions' 148 'The Fish, the Man, and the Spirit' 149 'Apollo and the Sunbeams' 151 From The Monthly Repository (1837) 'Blue-Stocking Revels; or, the Feast of the Violets' 153 'Doggrel on Double Columns and Large Type; or the praise of those pillars of our state, and its clear exposition' 180 From S. -

June 2016 President: Vice President: Simon Russell Beale CBE Nickolas Grace

No. 495 - June 2016 President: Vice President: Simon Russell Beale CBE Nickolas Grace Nothing like a Dame (make that two!) The VW’s Shakespeare party this year marked Shakespeare’s 452nd birthday as well as the 400th anniversary of his death. The party was a great success and while London, Stratford and many major cultural institutions went, in my view, a bit over-bard (sorry!), the VW’s party was graced by the presence of two Dames - Joan Plowright and Eileen Atkins, two star Shakespeare performers very much associated with the Old Vic. The party was held in the Old Vic rehearsal room where so many greats – from Ninette de Valois to Laurence Olivier – would have rehearsed. Our wonderful Vice-President, Nickolas Grace, introduced our star guests by talking about their associations with the Old Vic; he pointed out that we had two of the best St Joans ever in the room where they would have rehearsed: Eileen Atkins played St Joan for the Prospect Company at the Old Vic in 1977-8; Joan Plowright played the role for the National Theatre at the Old Vic in 1963. Nickolas also read out a letter from Ronald Pickup who had been invited to the party but was away in France. Ronald Pickup said that he often thought about how lucky he was to have six years at the National Theatre, then at Old Vic, at the beginning of his career (1966-72) and it had a huge impact on him. Dame Joan Plowright Dame Joan Plowright then regaled us with some of her memories of the Old Vic, starting with the story of how when she joined the Old Vic school in 1949 part of her ‘training’ was moving chairs in and out of the very room we were in. -

Larry D. Horricks Society of Motion Picture Stills Photographers

Larry D. Horricks Society of Motion Picture Stills Photographers www.larryhorricks.com Feature Films: Spaceman of Bohemia – Netflix – Johan Renck Director Cast – Adam Sandler, Carey Mulligan Producers: Michael Parets, Max Silva, Ben Ormand, Barry Bernardi White Bird – Lionsgate – Marc Forster Director (Unit + Specials_ Cast: Gillian Anderson ,Helen Mirren, Ariella Glaser, Orlando Schwerdt Producers: Marc Forster, Tod Leiberman, David Hoberman, Raquel J. Palacio Oslo – Dreamworks Pictures / Amblin / HBO / Marc Platt Prods.– Bart Sher Director (Unit + Specials) Cast: Ruth Wilson, Andrew Scott, Jeff Wilbusch,Salim Dau, Producers: Steven Spielberg, Kristie Macosko Krieger, Marc Platt, Cambra Overend, Mark Taylor Atlantic 437 – Netflix. Ratpack Entertainment – Director Peter Thorwath Producers: Chritian Becker,Benjamin Munz The Dig – Netflix, Magnolia Mae Films – Simon Stone Director Cast: Ralph Fiennes, Carey Mulligan, Lily James, Ken Stott, Johnny Flynn Producers: Gabrielle Tana, Carolyn Marks Blackwood, Redmond Morris A Boy Called Christmas – Netflix – Gil Kenan Director (Unit + Specials) Cast: Sally Hawkins, Kristen Wiig,Maggie Smith, Jim Broadbent, Toby Jones, Michiel Huisman, Harry Lawful Producers: Graham Broadbent, Pete Czernin, Kevan Van Thompson Minamata - Metalwork Pictures /HanWay Films / MGM - Andrew Levitas Director (Unit + Specials) Cast: Johnny Depp, Bill Nighy, Minami, Hiro Sanada, Ryo Kase, Sato Tadenobu, Jun Kunimura Producers: Andrew Levitas,Gabrielle Tana, Jason Foreman, Johnny Depp, Sam Sarkar, Stephen Deuters, Kevan