This File Was Downloaded From

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Allen&Heath Gl4000

ALLEN&HEATH GL4000 Dual Function Audio Mixing Console USER GUIDE PUBLICATION: AP2642 USER GUIDE CONTENTS Warranty ............................................................... 2 Introduction ........................................................... 3 Overview .............................................................. 4 Range and Options ............................................... 5 Dimensions and Weights ...................................... 6 Specifications ....................................................... 7 System Block Diagram ......................................... 8 Connectors ......................................................... 10 Earthing .............................................................. 13 Connecting the Power Unit ................................. 14 Matching the Signal Levels ................................. 15 Mono Input Channel ........................................... 16 Stereo Input Channel .......................................... 18 Stereo Channel Applications............................... 19 Group Section .................................................... 20 LR Section .......................................................... 21 Mono and Master Section ................................... 23 The Mute System ............................................... 26 Mute Groups ....................................................... 28 Mute Safes ......................................................... 31 Mute Patches ..................................................... 32 The Patch -

Amplified Music and Multimodality

Making Things Louder: Amplified Music and Multimodality PhD Thesis Johannes Mulder University of Technology Sydney Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences Supervisor: Professor Theo van Leeuwen Submitted April 2013 Certificate of Authorship/Originality I certify that the work in this thesis has not previously been submitted for a degree nor has it been submitted as part of requirements for a degree except as fully acknowledged within the text. I also certify that the thesis has been written by me. Any help that I have received in my research work and the preparation of the thesis itself has been acknowledged. In addition, I certify that all information sources and literature used are indicated in the thesis. Johannes Mulder ii Acknowledgments I am very grateful to Theo van Leeuwen who both inspired and supervised this thesis. In a relatively short time he has shared a vast amount of his own work and insights, forming the ‘roots’ of this work. Bert Bongers’ for his invaluable and continuing friendship, support and our never-ending critical dialogue. Tony Mitchell has kindly and patiently proofread this dissertation, which has been crucial in eliminating the inherent quirks of bilingualism (which in itself sounds like a Dutchism). Some of my best friends are live sound engineers: Paul, Joke, Bart, Jeroen, Carl, Marc, you are all part of this. Two people, Martje van Riel and Xander Lub were instrumental in making me go back to University. I particularly want to thank my friend Arnoud van Deelen (the self appointed chair of my fan club) for his long lasting support morally, and financially. -

Signature 10/12/12MTK User Guide

User Guide For Soundcraft Signature 10, 12 & 12MTK 10, 12, 12MTK User Manual INFORMATION INFORMATION IMPORTANT Please read this manual carefully before using your mixer for the first time. This equipment complies with the EMC directive 2004/108/EC and LVD 2006/95/EC. This product is approved to safety standards: IEC 60065:2005 (Seventh Edition) +A1:2005 EN60065:2006 +A1:2006 +A1:2008 UL60065 2012 7th Edition CAN/CSA-E60065-03 + A1: 2006 And EMC standards EN55103-1: 2009 (E2) EN55103-2: 2009 (E2) Warning: Any modification or changes made to this device, unless explicitly approved by Harman, will invalidate the authorisation of this device. Operation of an unauthorised device is prohibited under Section 302 of the Communications act of 1934, as amended, and Subpart 1 of Part 2 of Chapter 47 of the Code of Federal Regulations. NOTE: This equipment has been tested and found to comply with the limits for a Class B digital device, pursuant to Part 15 of the FCC Rules. These limits are designed to provide reasonable protection against harmful interference in a residential installation. This equipment generates, uses and can radiate radio frequency energy and, if not installed and used in accordance with the instructions, may cause harmful interference to radio communications. However, there is no guarantee that interference will not occur in a particular installation. If this equipment does cause harmful interference to radio or television reception, which can be determined by turning the equipment off and on, the user is encouraged to try to correct the interference by one or more of the following measures: * Reorient or relocate the receiving antenna. -

7 Things Every Live Sound Engineer Should Know by Michelle S Pettinato

7 Things Every Live Sound Engineer Should Know by Michelle S Pettinato © 2019+ Copyrighted Content by Michelle S Pettinato Cover Design and Layout by Grapevine Design No part of this eBook may be reproduced or transmitted in any form, by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying or recording or by any information storage or retrieval system, without express permission in writing from the author, except where brief passages are quoted for the purposes of review. 7 Things Every Live Sound Engineer Should Know Introduction Welcome! I’m excited to be sharing the information in this eBook with you. Mixing live music has been my passion for a long time and I’ve been fortunate to make a career out of it for nearly 30 years! During that time, I’ve met a lot of people interested in learning live sound but having no idea where to start. “What do I need to know”, they always ask? There is just so much to learn- from a wide range of audio consoles to system processing, so many different microphones, speaker systems, wireless systems, in-ear monitors, plug-ins, and that’s just technology! What about EQ techniques, power requirements, dealing with RF, how to get rid of feedback, how to choose the right microphones, how the whole sound system goes together… I’ve also encountered those who have been mixing sound for live shows and events but struggling to achieve their desired results, because they lack knowledge of the core principles. They just can’t quite get the vocals loud enough without feeding back or their mixes are lacking clarity and definition, everything is just muddy sounding or the instruments are all fighting for the same space. -

Vi6 Brochure

Soundcraft, Harman International Industries Ltd., Cranborne House, Cranborne Road, Potters Bar, Hertfordshire EN6 3JN, UK T: +44 (0)1707 665000 F: +44 (0)1707 660742 E: [email protected] Soundcraft USA, 8500 Balboa Boulevard, Northridge, CA 91329, USA T: +1-818-920-3212 F: +1-818-920-3208 E: [email protected] www.soundcraftdigital.com www.soundcraft.com Direct access to all functions with A compact operating surface with a Beyond intuitive. maximum information and visibility at perfectly optimised control density. all times. The time has come to forget the A unique integration of touch screens console and focus on the creativity. and encoders eliminating complex and The time has come for the fatigueing mental mapping. Soundcraft Vi6™ console. With more than 30 years in the confuses the operator and impedes the Soundcraft Vi6™ is a third business, no-one knows more about workflow. That’s why our first digital live generation digital live sound console live sound mixing than Soundcraft. In sound console puts the engineer at which abandons the layering and our opinion, there’s simply no point in the heart of the process, just like our assignability concepts of earlier presenting the live sound engineer with analogue mixers do. The product of a designs in favour of a system that’s the undeniable power and flexibility of development team that combines altogether more intuitive. digital audio technology if all that unrivalled Soundcraft live sound know- Say goodbye to the learning curve. power is locked away in an ill- how with the impressive digital audio Say hello to the Soundcraft Vi6 digital conceived and inaccessible mixer that expertise of our sister company Studer, Thirty years in the making. -

Live Sound Mixing Techniques Part 3 Issue 6

Live Sound Mixing Techniques In our continuing series on live sound, Konrad Skirlis looks at the soundcheck, preparation, and the art of mixing. ood live sound depends greatly on your familiarity with the where bass frequencies cancel out. Mixing in that sort of position room, so having time for a sound check is important in famil- will naturally produce a bass-heavy mix. Walking the room during Giarising yourself with the room. It not only helps sort out soundcheck is therefore important. Do not be compromised by a problems, it also provides performers with the opportunity to ‘hear’ promoter trying to sell seats where the mix position should be! If themselves as they would during the actual performance. A problematic reflections start bouncing off the back wall, setting up musician’s concern will primarily be for loud and clear stage theatre curtains may often be a quick solution. Otherwise, bridging monitors. If foldback is run from the mixing desk, stage monitoring the back-wall echo with an ‘in-between’ delay may help smooth out will be the responsibility of the front of house (FOH) mixer. If it’s a bouncing sound and provide a quick-fix on the night. big show, stage sound will be handled by a foldback mixer using a separate foldback desk located by the side of the stage. Good com- Preparing For The Mix munication and rapport with the foldback engineer can in itself For big rooms, it is necessary to listen to effects in the context of the influence good FOH sound on the night. -

Sound Engineering

SOUND ENGINEERING Edited by Prof. Chandrabhanu Pattanayak Practical Sound Engineering Ear Training for Mix Engineers Live Sound Engineering Live Sound Mixing Sound System Engineering Shaping Lives... Empowering Communities... SOUND ENGINEERING THE AUDIO TECHNIQUES (Aligned to MES/ Q 3402 of Media and Entertainment Skills Council, India) INSTITUTE OF KNOWLEDGE SOCIETIES CENTURION UNIVERSITY OF TECHNOLOGY AND MANAGEMENT Page 3 SOUND ENGINEERING This course has been developed with the support of the Commonwealth of Learning (COL). COL is an intergovernmental organisation created by Commonwealth Heads of Government to promote the development and sharing of open learning and distance education knowledge, resources and technologies. Centurion University of Technology and Management (CUTM) is a multicampus state private univesity in India offering liberal, professional and technical education in various dsciplines. The University focuses on ‗hands-on‘, ‗experience based‘, ‗practice oriented‘ learning. While promoting Nano, Mini and Micro Enterprises, the University works toward learning experiences that are ‗quantifiable‘, ‗sustainable‘, ‗scalable‘ and ‗replicable‘. CUTM is redefining the learning platform through: (i) skill integrated, domain linked, teaching and learning; (ii) industry and community partnerships; (iii) creating and co-creating enterprises; and (iv) an eco-system approach which includes community, enterprise, industry and educational institutes. © 2018 by the Commonwealth of Learning and Centurion University of Technology and Management. Except where otherwise noted, Digital Video Editing is made available under Creative Commons Attribution- ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-SA 4.0) License: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by- sa/4.0/legalcode . For the avoidance of doubt, by applying this licence the Commonwealth of Learning does not waive any privileges or immunities from claims that it may be entitled to assert, nor does the Commonwealth of Learning submit itself to the jurisdiction, courts, legal processes or laws of any jurisdiction. -

Powerful and Compact Digital Mixing System Powerful, Compact Mixing

Powerful and Compact Digital Mixing System Powerful, Compact Mixing An innovative console that fits anywhere. Easy to operate. Incredible sound. Roland introduced the modern V-Mixing System to the world in 2007. The V-Mixing System incorporates several models of V-Mixer Live Mixing Consoles, Digital Snakes for advanced digital audio transmission, the M-48 Personal Mixing System and the SONAR REAC Recording System for multi-channel recording. The V-Mixing System has been embraced the world over because of its high-quality sound, powerful features, extensibility and ease of operation. V-Mixing Systems are currently in use in live venues, touring and production, television and radio broadcasting/recording, as well as concert halls, educational institutions and houses of worship. The M-300 V-Mixer expands the number of V-Mixing System applications with a compact, highly portable chassis useable in any type of situation. The M-300 builds on the core V-Mixer feature set to represent the highest levels of performance at a breakthrough price. Introducing the M-300 V-Mixer. 2 32 mixing channels, L/C/R outputs, 8 AUX buses, 4 Matrices 4-band PEQ and dynamics on all channels 11 different built-in multi-effects/ PEQ and delay on all outputs 24bit AD/DA for high-quality sound Remotely controllable from a PC Record to /playback from USB flash memory Perfectly integrates with the Digital Snake for simple and high-quality audio transmission, distribution, splits and merging Construct a flexible and powerful system by adding the Personal Mixing System, multi-channel recording and other REAC components. -

Download the Soundcraft Si Expression Color Brochure

Typical Specifications Frequency Response Input & Output Levels Mic / Line Input to any Output . +/-1.5dB, 20Hz – 20kHz Mic Input . +22dBu max T.H.D. Line Input . +22dBu max Mic Sensitivity . -30dBu < 0.01% @ 1kHz Mix Output . +21.5dBu max Headphones (@150 Ω) . 300mW (recommended impedance 32 to 200 Ω) Noise Residual noise . -86dBu Input & Output Impedances Mic Input E.I.N. (maximum gain) . -126dBu (150 Ω source) Mic Input . 3k Ω Mix noise, masters at unity . < -86dBu Line Input . 10k Ω 1 input to mix at unity gain . -84dBu AES Input . 110 Ω CMRR mic @1kHz (max gain) . -80dBu Outputs . 150 Ω ( balanced ), 75 Ω ( unbalanced ) Word Clock used as Output . 50 Ω Crosstalk (@ 1kHz) Word Clock used as Input . 4k7 Ω Channel ON attenuation . <120dB AES Output . 110 Ω Channel Fader attenuation . <120dB Mic – Mic . -100dB @ 1kHz, -85dB @ 10kHz Lamp Output Line – Line . -100dB @ 1kHz, -85dB @ 10kHz 12v DC . 100mA max (per socket) Input Gain Power Mic Gain . -5dB – 58dB integrated pad design 1dB steps Consumption (typical) . <130w Si Expression 3 Line Trim . -10dB - +16dB AC Input voltage range . 88-264VAC auto sensing EQ AC Frequency range . 47-63Hz HI MID & LO MID . 22Hz – 20kHz, +/-15dB Q 6-0.3 Operating Conditions Shelf (HF) . 800Hz – 20kHz, +/-15dB Operating Temperature Range . 5°C to 45°C Shelf (LF) . 20Hz – 500Hz, +/-15dB Humidity . 0%-90%, non condensing Ta=40°C (104°F) HPF . 40Hz – 1kHz Storage Temperature Range . -20°C to 60°C (-4°F to 140°F) GEQ . 31Hz – 16kHz 1/3 octave Weights and Dimensions (net) . Delay Si Expression 1 User adjustable delay . -

Gigrac 300 Brochure-English

Soundcraft At the heart of live sound Ever since 1973, Soundcraft live sound mixing technology has been at the heart of thousands PROFESSIONAL POWERED MIXER of memorable concert and festival performances. Soundcraft products are relied upon daily by GIGRAC 300 / GIGRAC 600 discerning sound engineers to deliver the performances of leading artists the world over. GigRac benefits directly from everything we’ve learned in 30 years in the business, so when you’re on stage with a GigRac, you’re always in good company. Texas: On tour with Soundcraft GREAT SOUND MADE EASY Soundcraft HARMAN INTERNATIONAL INDUSTRIES LTD CRANBORNE HOUSE, CRANBORNE ROAD, POTTERS BAR, HERTS, EN6 3JN, UK TEL: +44 (0)1707 665000 FAX: +44 (0)1707 660742 EMAIL: [email protected] Soundcraft USA 8500 BALBOA BLVD., NORTHRIDGE, CA 91329, USA TEL: +1-818-920-3212 FAX: +1-818-920-3208 EMAIL: [email protected] For all the latest GigRac news and information, visit: www.gigrac.com Soundcraft reserves the right to improve or otherwise alter any information supplied in this document or any other documentation supplied hereafter. E&OE 01/04. This equipment complies with the EMC Directive 89/336/EEC Part No: ZL0612 Comprehensive channel controls The amplifier assignment include Bass and Treble for tone Just like a professional GigRac has eight The switchable 7-band switch featured on the shaping, an FX send to control the mixing console, +48V high-quality digital graphic equaliser GigRac 600 provides an 10-segment precision LED amount of signal sent to the digital FX phantom -

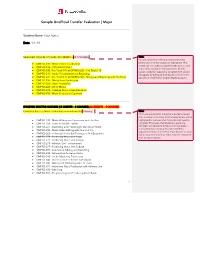

Sample Unofficial Transfer Evaluation | Major

Sample Unofficial Transfer Evaluation | Major Student Name: Your Name Date: 1/1/18 REQUIRED ONLINE COURSES (30 CREDITS – 10 COURSES) Note: You will notice that nothing is crossed off in this ● OMPRD-160 - Music Production Analysis section and all of the courses are highlighted. This means that the student’s transfer credit will not fulfill ● OMPRD-162 - Critical Listening 1 any of these courses in this requirement and the ● OMPRD-180 - Pro Tools 101 or OMPRD-221 - Pro Tools 110 student would be required to complete them should ● OMPRD-210 - Audio Fundamentals for Recording they apply, be admitted, and decide to enroll in the ● OMPRD-221 - Pro Tools 110 or OMPRD-380 - Mixing and Mastering with Pro Tools Bachelor of Professional Studies degree program. ● OMPRD-355 - Microphone Techniques ● OMPRD-365 - Vocal Production ● OMPRD-420 - Art of Mixing ● OMPRD-475 - Creative Music Production Skills ● OMPRD-498 - Music Production Capstone SPECIFIED ELECTIVE COURSES (15 CREDITS – 5 COURSES) (12 CREDITS – 4 COURSES) Complete five four Music Production courses from the following: Note: For those requirements that allow a student to select from a number of courses, only the requirement will be ● OMPRD-205 - Music Writing and Production with the iPad highlighted to indicate what the student will need to ● OMPRD-208 - Learn to DJ with Traktor complete. This means that should you apply, be ● OMPRD-227 - Recording and Producing in the Home Studio admitted, and decide to enroll, you will be able to choose from the courses in this list to fulfill this ● OMPRD-250 - Music Video Editing with Final Cut Pro requirement. -

Dme64n / Dme24n

DIGITAL MIXING ENGINE DME64N / DME24N Programmabilityogrammability ProcessingProcessing PowerPow Intuitivelyively configuredconfigured usingusing CustomCustom cchipsethipset sspeciallypec Totally reliable yet utterly flexible, in the fields of is … PPCC softwarsoftwaree devedevelopedloped by YamahaYama Integrating a chipset specifically developed for the processing of digital signals, the broadcasting and music production, Yamaha's digital mixing engines of the Yamaha DME Series constitute DSP boxes with Network I/O/O SoundSou Quality exceptional processing power. Using a dedicated PC application, systems can be Compatible with CobraNetaNet and Excellent ssound quality inherited EtherSound digital aaudioudio from YaYamaham digital consoles DME Series is second to none. intuitively and flexibly assembled from a myriad of components such as mixers, networks equalizers, and compressors in addition to the delays, limiters, de-essers, matrix mixers,, While it goes without saying that mixing solutions for broadcasting stations and professional music-production studios must deliver routers, and other processors that are indispensable in the fields of broadcasting and excellent sound and performance, total reliability is the true mark of quality. The digital mixing engines of the Yamaha DME Series comfort- music production. Components may also be combined as powerful functional blocks, ScalabilityScalability EconomyEconomy Supportort for all systemsystem sizessizes,, which can then be arranged to create innovative solutions for downmixing, bass DramaticDramatic reductionreduction from the comcompactpact ably and efficiently satisfy this need. To achieve steadfast reliability, functional components are freely and flexibly assembled using a iin cablingbli costst management, and other critical processes in surround sound systems. Of course, these to the massive dedicated PC application in order to create systems where physical connections and wiring are reduced to the absolute minimum.