Aboriginal Interactions with People from the Pacific Darren Friesen

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

First Nations Nutrition and Health Conference

First Nations Nutrition and Health Conference Proceedings Alfred Wong, Editor June 19 - 20, 2003 Recreation Centre, 100 Lower Capilano Road, Squamish Nation Sponsored by Friends of Aboriginal Health 2 Notice The Friends of Aboriginal Health through a copyright agreement with Arbokem Inc. permits the unlimited use of the content of the proceedings of the First Nations Nutrition and Health Conference, for the non-commercial promotion of health and wellness among the people of the First Nations. ISBN: 0-929020-02-3 © Arbokem Inc., Vancouver, Canada, 2003-2004 www.aboriginalhealth.net Printed in Canada AK25818W2 Proceedings of the First Nations Nutrition and Health Conference, 2003 3 Table of Content Page Notice 2 Table of Content 3 Foreword 5 Conference Program 6 Time for justice, sovereignty and health after more than 200 years of foreign 8 colonization and cultural destruction. Ovide Mercredi The Present Status of Aboriginal Health in British Columbia. Lydia Hwitsum 9 Health of the people and community. Gerald Amos 16 Loss of Use of a Traditional Fishery – The Kitamaat Eulachon. Michael Gordon 17 Wellness Governing Mode: The Union of Our Two Worlds and Traditional 18 Knowledge. Andy Carvill and David Anthony Ravensdale Environmental Impact on Food and Lifestyle. :Wik Tna A Seq Nakoo (Ida John) 19 “Our Food is Our Medicine”: Traditional Plant Foods, Traditional Ecological 22 Knowledge and Health in a Changing Environment. Nancy J. Turner and Rosemary Ommer Acculturation and natural food sources of a coastal community. Wata (Christine 40 Joseph) Impact of Fish Farming on the Natural Food Resources of 41 First Nations People. Sergio Paone Overall Health - Mental, Emotional, Spiritual and Physical Aspects. -

Songhees Pictorial

Songhees Pictorial A History ofthe Songhees People as seen by Outsiders, 1790 - 1912 by Grant Keddie Royal British Columbia Museum, Victoria, 2003. 175pp., illus., maps, bib., index. $39.95. ISBN 0-7726-4964-2. I remember making an appointment with Dan Savard in or der to view the Sali sh division ofthe provincial museum's photo collections. After some security precautions, I was ushered into a vast room ofcabi nets in which were the ethnological photographs. One corner was the Salish division- fairly small compared with the larger room and yet what a goldmine of images. [ spent my day thumbing through pictures and writing down the numbers name Songhees appeared. Given the similarity of the sounds of of cool photos I wished to purchase. It didn't take too long to some of these names to Sami sh and Saanich, l would be more cau see that I could never personally afford even the numbers I had tious as to whom is being referred. The oldest journal reference written down at that point. [ was struck by the number of quite indicating tribal territory in this area is the Galiano expedi tion excellent photos in the collection, which had not been published (Wagner 1933). From June 5th to June 9th 1792, contact was to my knowledge. I compared this with the few photos that seem maintained with Tetacus, a Makah tyee who accompanied the to be published again and again. Well, Grant Keddie has had expedi tion to his "seed gathering" village at Esquimalt Harbour. access to this intriguing collection, with modern high-resolution At this time, Victoria may have been in Makah territory or at least scanning equipment, and has prepared this edited collecti on fo r high-ranking marriage alliances gave them access to the camus our v1ewmg. -

Taylor Dayne Supermodel Download

Taylor dayne supermodel download Taylor Dayne Supermodel. Now Playing. Supermodel. Artist: Taylor Dayne. MB · Supermodel. Artist: Taylor Dayne. MB. Hymn. Artist: Taylor Dayne. MB · Supermodel. Artist: Taylor Dayne. MB · Supermodel. Artist: Taylor. Artist: Taylor Dayne. test. ru MB. Supermodel Free Mp3 Download Free RuPaul Supermodel You Better Work mp3. Kbps MB Free Taylor Dayne Supermodel. Taylor Dayne Supermodel mp3 high quality download at MusicEel. Choose from several source of music. Download Supermodel Taylor Dayne mp3 songs in. "Taylor Dayne - Supermodel" Music Lyrics. You better You better work! [covergirl]Work it girl! [give a twirl]Do your thing on the ! Stream Taylor Dayne - Supermodel Jack Smith Edit by Jack Smith from desktop or your mobile device. Listen to songs and albums by Taylor Dayne, including "Tell It to My Heart", of RuPaul's "Supermodel" for The Lizzie McGuire Movie -- acting kept her away. Watch the video, get the download or listen to Taylor Dayne – Supermodel for free. Supermodel appears on the album The Lizzie McGuire Movie. Discover more. Check out RuPaul. SuperModel (You Better Work) ReMixes from RuCo, Inc. on Beatport. Supermodel performed by Taylor Dayne taken from the Lizzie McGuire Motion Picture Soundtrack starring. Tags: Taylor Dayne Supermodel (You Better Work) Fashion Singing lyrics lyric with super model lizzie mcguire movie track hilary duff Full music Song Album. Supermodel - Taylor Dayne. What Dreams Are Made Of - Lizzie McGuire. On An Evening In Roma - Dean Martin. Girl In The Band - Haylie Duff. Floor On Fire written by Taylor Dayne, Niclas Kings, Ivar Lisinski & Tania Download now on iTunes: http. Taylor Dayne, Soundtrack: Win a Date with Tad Hamilton!. -

Experience the Fraser Concept Plan Overview

City of Report to Committee Richmond inR4:s -dvy,g_2 -\::? ;?i)t2- To: Parks, Recreation and Cultural Services Date: May 31 , 2012 Committee From: Dave Semple File: 06-2400-01/201 2-Vol General Manager, Parks and Recreation 01 Re: Experience the fraser Concept Plan Overview Staff Recommendation Then the Experience the Fraser: Lower Fraser River Corridor Project Concept Plan as described in attachment 1 of the report, Experience the Fraser Concept Plan Overview, dated May 22nd 2012 from the General Manager, Parks and Recreation, be endorsed as a regionally beneficial initiative. ave ern Ie ral Manager, Parks and Recreation (604-233-3350) Au. 1 REPORT CONCURRENCE ROUTED TO: CONCURRENCE CONCURRENCE OF G ENERAL MANAGER Arts, Culture & Heritage ~ ~~ / REVIEWED BY TAG INITIALS: REVI E~ AO SUBCOMMITIEE ~ m 3~ 4 S%2 CNCL - 45 ___-' M"'ay--1L 2012 - 2 - Staff Report Origin The Experience the Fraser (ETF) project is a Provincial Government initiative to raise awareness and showcase the rich recreational, cultural and natural heritage of the Lower Fraser Corridor from Hope to the Salish Sea. In 2009, Metro Vancouver and the Fraser Vall ey Regional District rece ived $2.0 million to develop a comprehensive plan for a continuous recreational corridor on both sides ofthe main river - the south ann of the Fraser. City staff have provided input into this concept plan by meeting with regional staff, attending workshops, and providing background information from the City's many existing strategic plans and documents. A draft concept plan has now been completed and was endorsed in principle by both the Metro Vancouver and Fraser Valley Regional District Boards in October 20 11. -

Johannes Oerding Linkin Park Rammstein Die Toten Hosen Astral Doors Diana Krall Paul Weller Mando Diao the Beatles Inhalt

GRATIS | MAI 2017 Ausgabe 38 JOHANNES OERDING LINKIN PARK RAMMSTEIN DIE TOTEN HOSEN ASTRAL DOORS DIANA KRALL PAUL WELLER MANDO DIAO THE BEATLES INHALT INHALT EDITION – IMPRESSUM 03 BLONDIE HERAUSGEBER 04 JOHANNES OERDING AKTIV MUSIK MARKETING GMBH & CO. KG 05 RAMMSTEIN | DIE TOTEN HOSEN Steintorweg 8, 20099 Hamburg, UstID: DE 187995651 06 LINKIN PARK PERSÖNLICH HAFTENDE GESELLSCHAFTERIN: 07 MANDO DIAO | THE KOOKS | HELEN SCHNEIDER AKTIV MUSIK MARKETING 08 THE BEATLES | PAUL WELLER VERWALTUNGS GMBH & CO. KG 09 IRON MAIDEN | FOREIGNER | KRAFTWERK Steintorweg 8, 20099 Hamburg 10 HARRY STYLES | NATALIA AVELON | SITZ: Hamburg, HR B 100122 THOMAS AZIER GESCHÄFTSFÜHRER Marcus-Johannes Heinz 11 ÁSGEIR | FAYZEN | JAKE ISAAC FON: 040/468 99 28-0 Fax: 040/468 99 28-15 12 HELENE FISCHER | ALEJANDRA RIBERA | E-MAIL: [email protected] MIA AEGERTER 13 GUARDIANS OF THE GALAXY | ELIF | REDAKTIONS- UND ANZEIGENLEITUNG THE BOSSHOSS Daniel Ahrweiler (da) (verantwortlich für den Inhalt) 14 DIANA KRALL | LESLIE CLIO 15 JOHN MAYER | KENDRICK LAMAR | THE WHOLLS MITARBEITER DIESER AUSGABE 16 ASTRAL DOORS | DIE NEGATION | Marcel Anders (ma), Kai Florian Becker (kfb), WHILE SHE SLEEPS Helmut Blecher (hb), Dagmar Leischow (dl), 17 ALBUM-TIPPS Steffen Rüth (sr), Anja Wegner, Nadine Wenzlick (nw) 21 DAS LÄUFT IM LADEN 22 PLATTENLADEN DES MONATS | PLATTENLÄDEN FOTOGRAFEN DIESER AUSGABE 23 TOP 20 VINYL-CHARTS Kristina Wagenbauer (2 Alejandra Ribera), Alexander Thompson (3 Blondie), Marcel Schaar Bleibe auf dem Laufenden und bestelle unseren Newsletter auf (4 Johannes Oerding), -

COAST SALISH SENSES of PLACE: Dwelling, Meaning, Power, Property and Territory in the Coast Salish World

COAST SALISH SENSES OF PLACE: Dwelling, Meaning, Power, Property and Territory in the Coast Salish World by BRIAN DAVID THOM Department of Anthropology, McGill University, Montréal March, 2005 A thesis submitted to McGill University in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy © Brian Thom, 2005 Abstract This study addresses the question of the nature of indigenous people's connection to the land, and the implications of this for articulating these connections in legal arenas where questions of Aboriginal title and land claims are at issue. The idea of 'place' is developed, based in a phenomenology of dwelling which takes profound attachments to home places as shaping and being shaped by ontological orientation and social organization. In this theory of the 'senses of place', the author emphasizes the relationships between meaning and power experienced and embodied in place, and the social systems of property and territory that forms indigenous land tenure systems. To explore this theoretical notion of senses of place, the study develops a detailed ethnography of a Coast Salish Aboriginal community on southeast Vancouver Island, British Columbia, Canada. Through this ethnography of dwelling, the ways in which places become richly imbued with meanings and how they shape social organization and generate social action are examined. Narratives with Coast Salish community members, set in a broad context of discussing land claims, provide context for understanding senses of place imbued with ancestors, myth, spirit, power, language, history, property, territory and boundaries. The author concludes in arguing that by attending to a theorized understanding of highly local senses of place, nuanced conceptions of indigenous relationships to land which appreciate indigenous relations to land in their own terms can be articulated. -

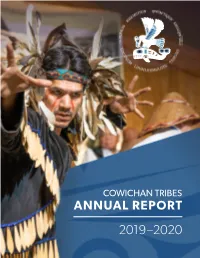

Annual Report 2019–2020 the Quw’Utsun Snuw’Uy’Ulh (Teachings) Welcome, Dear Reader

COWICHAN TRIBES ANNUAL REPORT 2019–2020 THE QUW’UTSUN SNUW’UY’ULH (TEACHINGS) WELCOME, DEAR READER Tl’i’ to’ mukw’ mustimuhw Each person is important Live in harmony with nature Hwial’asmut ch tun’ s-ye’lh Do the best you can, be the ABOUT THIS REPORT Take care of your health best you can be This Annual Report provides a detailed overview of Cowichan Tribes’ operations and financial performance during the fiscal year 2019-2020 (April 1st 2019 to March 31st 2020). ’Iyusstuhw tun’a kweyul Be honest and truthful in Enjoy today all you do and say This report includes updates from Cowichan Tribes departments and Economic Development entities. In accordance with Cowichan Tribes’ Financial Administration Law, this report also includes our audited Hwial’asmut tu tumuhw Learn from one another financial statements for the fiscal year 2019-2020. Take care of the earth Respect the rights of one another The goal of this Annual Report is to provide accountability and transparency to Cowichan Tribes Hiiye’yutul tst ’u to’ mukw’ members, and highlight the good work of our Nation as well as some of the challenges we are facing. Thank you for taking the time to read this report. stem ’i’u tun’a tumuhw Respect your leaders and Everything in nature is part of their decisions our family – we are all relatives ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Respect your neighbours Yath ch ’o’ lhq’il’ We are grateful to Quw’utsun Sul’wheen (Elders), youth, and community members for guiding our work. Be positive Take responsibility for your actions We are grateful to all Cowichan Tribes leaders and staff for their work to make Cowichan Tribes a healthier, safer, and stronger Nation. -

Click to Download

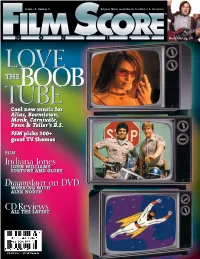

Volume 8, Number 8 Original Music Soundtracks for Movies & Television Rock On! pg. 10 LOVE thEBOOB TUBE Cool new music for Alias, Boomtown, Monk, Carnivàle, Penn & Teller’s B.S. FSM picks 100+ great great TTV themes plus Indiana Jones JO JOhN WIllIAMs’’ FOR FORtuNE an and GlORY Dragonslayer on DVD WORKING WORKING WIth A AlEX NORth CD Reviews A ALL THE L LAtEST $4.95 U.S. • $5.95 Canada CONTENTS SEPTEMBER 2003 DEPARTMENTS COVER STORY 2 Editorial 20 We Love the Boob Tube The Man From F.S.M. Video store geeks shouldn’t have all the fun; that’s why we decided to gather the staff picks for our by-no- 4 News means-complete list of favorite TV themes. Music Swappers, the By the FSM staff Emmys and more. 5 Record Label 24 Still Kicking Round-up Think there’s no more good music being written for tele- What’s on the way. vision? Think again. We talk to five composers who are 5 Now Playing taking on tough deadlines and tight budgets, and still The Man in the hat. Movies and CDs in coming up with interesting scores. 12 release. By Jeff Bond 7 Upcoming Film Assignments 24 Alias Who’s writing what 25 Penn & Teller’s Bullshit! for whom. 8 The Shopping List 27 Malcolm in the Middle Recent releases worth a second look. 28 Carnivale & Monk 8 Pukas 29 Boomtown The Appleseed Saga, Part 1. FEATURES 9 Mail Bag The Last Bond 12 Fortune and Glory Letter Ever. The man in the hat is back—the Indiana Jones trilogy has been issued on DVD! To commemorate this event, we’re 24 The girl in the blue dress. -

Victoria West Profile and Baseline Report

Victoria West Community Profile and Baseline Conditions Report DRAFT Created for the Victoria West Neighbourhood Plan September 2016 The Victoria West Community Profile highlights key baseline information and aspects of the unique features of the Victoria West neighbourhood. This information will help inform community discussions on various planning issues that will be addressed through the neighbourhood planning process. Contents Introduction ............................................................................5 Neighbourhood Context .........................................................6 Key Locations and Points of Interest ...................................... 7 Background and Objectives ...................................................8 Purpose of the Plan ...............................................................9 About this Baseline Review .................................................10 Relevant Plans and Policies ................................................ 11 OCP Strategic Directions .....................................................15 Community Overview ..........................................................17 Existing Land Use ................................................................ 18 Population Density ............................................................... 19 Demographics ...................................................................... 20 Housing ................................................................................ 22 Transportation and Mobility ................................................. -

Pacific Coast Salish Art and Artists: Educator Resource Guide

S’abadeb— TheGifts: PacificCoast SalishArt &Artists SEATTLE ART MUSEUM EDUCATOR RESOURCE GUIDE Grades3-12 SeattleArtMuseum S’abadeb—The Gifts: Pacific Coast Salish Art and Artists 1300 First Avenue is organized by the Seattle Art Museum and made Seattle, WA 98101 206.654.3100 possible by a generous leadership grant from The Henry seattleartmuseum.org Luce Foundation and presenting sponsors the National Endowment for the Humanities and The Boeing Company. © 2008 Seattle Art Museum This project is supported in part by an award from the National Endowment for the Arts with major support Pleasedirectquestionsabout thisresourceguideto: provided by the Mayor’s Office of Arts & Cultural Affairs, Adobe Systems, Incorporated, PONCHO, Washington State School & Educator Programs Arts Commission, and U.S. Bancorp Foundation. Additional Seattle Art Museum, 206.654.3146 [email protected] support provided by the Native Arts of the Americas and Oceania Council at the Seattle Art Museum, Thaw Exhibitionitinerary: Charitable Trust, Charlie and Gayle Pancerzewski, Suquamish Seattle Art Museum Clearwater Casino Resort, The Hugh and Jane Ferguson October 24, 2008–January 11, 2009 Foundation, Humanities Washington, Kreielsheimer Exhibition Endowment and contributors to the Annual Fund. Royal British Columbia Museum November 20–March 8, 2010 Art education programs and resources supported in Editing: John Pierce part by PONCHO and the Harrington-Schiff Foundation. Author: Nan McNutt Illustrations: Greg Watson ProjectManager: -

Brae Island Regional Park Managament Plan

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS During the process of creating the Brae Island Regional Park Management Plan, many outside organizations, agencies and individuals provided perspectives and expertise. We recognize the contribution of representatives from the Fort Langley Community Association, Fort Langley Business Improvement Association, Langley Heritage Society, Langley Field Naturalists, Fort Langley Canoe Club, BC Farm Machinery and Agriculture Museum, Langley Centennial Museum and National Exhibition Centre, Greater Langley Chamber of Commerce, Equitas Developments, Wesgroup, Kwantlen First Nation, Ministry of Water, Land and Air Protection, Department of Fisheries and Oceans, Agricultural Land Commission, Parks Canada, and especially, the Township of Langley. Thanks also go to our consultants including: Phillips Farevaag Smallenberg Landscape Architects, Strix Environmental Consultants, Northwest Hydraulics Consulting, GP Rollo & Associates, Tumia Knott of Kwantlen First Nation and Doug Crapo. Special thanks go out to: Board members from the Derby Reach/Brae Island Regional Park – Park Association; and Stan Duckworth, operator of Fort Camping. We also remember Don McTavish who saw the potential of creating a camping experience on Brae Island. While many GVRD staff from its Head and East Area Offices assisted this planning process special mention should go to the planning and research staff, Will McKenna, Janice Jarvis and Heather Wornell. Finally, we wish to thank all of those members of the public who regularly attended meetings and contributed their valuable time and insights to the Plan. Wendy DaDalt GVRD Parks Area Manager East Area TABLE OF CONTENTS ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ LETTER OF CONVEYANCE ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY.............................................................................. 1 1.0 INTRODUCTION................................................................................ 3 1.1 Brae Island Regional Park and the GVRD Parks and Greenways System....................................... -

Smallpox and Identity Reformation Among the Coast Salish Keith Thor Carlson

Document généré le 27 sept. 2021 02:56 Journal of the Canadian Historical Association Revue de la Société historique du Canada Precedent and the Aboriginal Response to Global Incursions: Smallpox and Identity Reformation Among the Coast Salish Keith Thor Carlson Global Histories Résumé de l'article Histoires mondiales Les réactions des Autochtones par rapport à la mondialisation ont été variées Volume 18, numéro 2, 2007 et complexes. Cette communication examine une expression particulière de l’internationalisme (épidémies au sein de la Première nation Coast Salish du URI : https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/018228ar sud-ouest de la C.-B. et nord-ouest de l’État Washington par suite du contact DOI : https://doi.org/10.7202/018228ar avec les Européens) et le situe dans le contexte des premières catastrophes régionales telles que comprises aux moyens des légendes. De cette façon, l’article recadre un des paradigmes d’interprétation standard du domaine – à Aller au sommaire du numéro l’effet que les épidémies étaient sans précédent et qu’elles représentaient peut-être la plus importante « rupture » de l’histoire autochtone. L’article montre les façons dont les communautés et les membres de la Première nation Éditeur(s) Coast Salish ont affronté les désastres. Il conclut que les histoires anciennes fournissaient au peuple des précédents qui façonnaient ensuite sa réaction à The Canadian Historical Association/La Société historique du Canada l’internationalisme. L’article illustre comment les historiens peuvent puiser dans les façons de raconter des Autochtones, dans lesquelles les généalogies, ISSN les légendes mythiques et les endroits spécifiques jouent des rôles cruciaux.