Conservation Bulletin 39

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Medieval Rural Settlement

15 Medieval rural settlement Mick Aston Early research Ann Hamlin, then at Exeter University and now an archaeologist in Northern Ireland, began to collect In The Lost Villages of England Maurice Beresford further data on sites in Somerset and this card index (1954) listed only 15 deserted medieval villages in was supplied to the writer when he became the first Somerset. These were mainly culled from easily county archaeologist for Somerset in 1974. available sources such as Collinson (1791), places Somerset, unlike adjacent counties, had had no big listed as having fewer than ten inhabitants in 1428 set piece deserted medieval village excavation in the and settlements which had lost their parish churches. 1960s, though Philip Rahtz had looked at a small Little was recorded from field evidence although area of the Barrow Mead site near Bath. In Wiltshire Maurice did correspond with field walkkers who extensive work had been carried out at Gomeldon alerted him to certain sites. near Salisbury, in Gloucestershire Upton in Brockley on the Cotswolds had been examined by Philip Rahtz and Rodney Hilton and in Dorset, Holworth was excavated. By 1971 when Maurice Beresford and John Hurst edited a series of studies (Deserted Medieval Villages) Somerset was credited with 27 sites – four of which, derived from documents, had not been located. A few of the other sites had been located from field evidence but the majority were still iden- tified from historical sources (see Aston 1989). Research in the 1970s Figure 15.1: Air photograph of Sock Dennis near Ilchester showing the characteristic earthworks of a As part of the writer’s duties as County Archaeolo- deserted medieval settlement site. -

Mick Aston Archaeology Fund Supported by Historic England and Cadw

Mick Aston Archaeology Fund Supported by Historic England and Cadw Mick Aston’s passion for involving people in archaeology is reflected in the Mick Aston Archaeology Fund. His determination to make archaeology publicly accessible was realised through his teaching, work on Time Team, and advocating community projects. The Mick Aston Archaeology Fund is therefore intended to encourage voluntary effort in making original contributions to the study and care of the historic environment. Please note that the Mick Aston Archaeology Fund is currently open to applicants carrying out work in England and Wales only. Historic Scotland run a similar scheme for projects in Scotland and details can be found at: http://www.historic-scotland.gov.uk/index/heritage/grants/grants-voluntary-sector- funding.htm. How does the Mick Aston Archaeology Fund work? Voluntary groups and societies, but also individuals, are challenged to put forward proposals for innovative projects that will say something new about the history and archaeology of local surroundings, and thus inform their future care. Proposals will be judged by a panel on their intrinsic quality, and evidence of capacity to see them through successfully. What is the Mick Aston Archaeology Fund panel looking for? First and foremost, the panel is looking for original research. Awards can be to support new work, or to support the completion of research already in progress, for example by paying for a specific piece of analysis or equipment. Projects which work with young people or encourage their participation are especially encouraged. What can funding be used for? In principle, almost anything that is directly related to the actual undertaking of a project. -

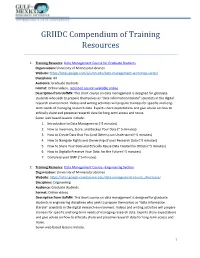

GRIIDC Compendium of Online Data Management Training Resources

GRIIDC Compendium of Training Resources 1. Training Resource: Data Management Course for Graduate Students Organization: University of Minnesota Libraries Website: https://sites.google.com/a/umn.edu/data-management-workshop-series/ Disciplines: All Audience: Graduate students Format: Online videos, recorded session available online Description from UofMN: This short course on data management is designed for graduate students who seek to prepare themselves as “data information literate” scientists in the digital research environment. Videos and writing activities will prepare trainees for specific and long- term needs of managing research data. Experts share expectations and give advice on how to ethically share and preserve research data for long-term access and reuse. Seven web based lessons include: 1. Introduction to Data Management (~5 minutes) 2. How to Inventory, Store, and Backup Your Data (~ 5 minutes) 3. How to Create Data that You (and Others) can Understand (~5 minutes) 4. How to Navigate Rights and Ownership of your Research Data (~9 minutes) 5. How to Share Your Data and Ethically Reuse Data Created by Others (~5 minutes) 6. How to Digitally Preserve Your Data for the Future (~5 minutes) 7. Complete your DMP (~5 minutes) 2. Training Resource: Data Management Course –Engineering Section Organization: University of Minnesota Libraries Website: https://sites.google.com/a/umn.edu/data-management-course_structures/ Disciplines: Engineering Audience: Graduate students Format: Online videos Description from UofMN: This short course on data management is designed for graduate students in engineering disciplines who seek to prepare themselves as “data information literate” scientists in the digital research environment. Videos and writing activities will prepare trainees for specific and long-term needs of managing research data. -

August 2012, No. 44

In 2011, the project members took part in excavations at East Chisenbury, recording and analysing material exposed by badgers burrowing into the Late Bronze Age midden, in the midst of the MoD’s estate on Salisbury Plain. e season in 2012 at Barrow Clump aims to identify the extent of the Anglo-Saxon cemetery and to excavate all the burials. is positive and inspiring example of the value of archaeology has recently been recognised at the British Archaeological Awards with a special award for ‘Project of special merit’. You will find two advertising flyers in this mailing. Please consider making a gi of member - ship to a friend or relative for birthday, Christmas or graduation. Details of subscription rates appear in the notices towards the end of this Newsletter. FROM OUR NEW PRESIDENT David A. Hinton Professor David Hinton starts his three-year term as our President in October, when Professor David Breeze steps down. To follow David Breeze into the RAI presidency is daunting; his easy manner, command of business and ability to find the right word at the right time are qualities that all members who have attended lectures, seminars and visits, or been on Council and committees, will have admired. Our affairs have been in very safe hands during a difficult three years. In the last newsletter, David thanked the various people who have helped him in that period, and I am glad to have such a strong team to support me in turn. ere will be another major change in officers; Patrick Ottaway has reached the end of his term of editorship, and has just seen his final volume, 168, of the Archaeological Journal through the press; he has brought in a steady stream of articles that have kept it in the forefront of research publication. -

The Archaeology of the Isle of Man: CBA Members' Tour for 2016

Issue 37, June - September 2016 Picture courtesy of ‘Go Mann Adventures’ – www.go-mannadventures.com of ‘Go Mann Adventures’ courtesy Picture The archaeology of the Isle of Man: CBA members’ tour for 2016 Page 12 04 What does your MP know 06 Inspiring young 10 Valuing community about archaeology? archaeologists research www.archaeologyUK.org ISSUETHIRTYSEVEN LATEST NEWS LATEST NEWS Have we found the seat The Festival A of Archaeology A M YA of the Brigantian queen N M ’ ! draws near I M s Cartimandua? t i s c i We are happy to announce that the latest CBA research This year’s Festival of Archaeology takes place between k g o 16 and 31 July. This annual celebration of all things A l report: Cartimandua’s Capital?: The late Iron Age Royal Site s o e at Stanwick, North Yorkshire, Fieldwork and Analysis archaeological offers more than 1,000 events nationwide, to a n h 1981–2011 is due to be published in June. giving everyone a way to discover, experience, explore, and ’s rc Last year’s Young Archaeologist of Y A enjoy the past. As Phil Harding, renowned TV archaeologist, oung the Year, William Fakes Famous for the excavations carried out by Sir Mortimer Wheeler in 1951–52, the says “The Festival gives archaeologists the chance to open late Iron Age earthwork complex at Stanwick, North Yorks, is the largest their doors and invite people in”. Nominations prehistoric site in northern England. The site was probably the seat of the Brigantian New Young now open for Marsh queen Cartimandua, and both the structures and the finds from the site reflect this This is our chance to make our discipline as accessible as possible to new Archaeologists’ status. -

Preservation Best Practices 3D Methods and Workflows: Photogrammetry Case Study (Repository Perspective)

Preservation Best Practices 3D Methods and Workflows: Photogrammetry Case Study (Repository Perspective) Kieron Niven Your Name Digital Archivist, Archaeology Data Service 13th August 2018 http://archaeologydataservice.ac.uk 1 Same basic structure but: ● From the perspective of a repository: ○ What do we need to know about a photogrammetry project and the associated data ○ How this should be deposited, structured, archived ● Largely looking at Photogrammetry... ● Many of the points are equally applicable to other data types (laser scan, CT, etc.) http://archaeologydataservice.ac.uk Planning Phase ● Engage with project at point of start up / data creation - advise on suitable formats and metadata ● Aim to exploit exports and tools for recording metadata. ● Not always possible (legacy projects). Relevant project documents, reports, methodology, process, etc. Should also be archived to describe as much as possible of the project design, creators, and intentions. ● Data should be linked to wider context through IDs, DOIs, references (external documents, creators/source of data, monument ids, museum ids, etc.) http://archaeologydataservice.ac.uk Planning Phase • Planning phase is the most important phase • Both ‘Purpose’ and ‘Audience’ will influence what is recorded, how it’s recorded, and what are produced as final deliverables (e.g. LOD, opportunist/planned, subsequent file migrations, limited dissemination options). http://archaeologydataservice.ac.uk Planning Phase ACCORD: Project documentation. Specific project aims and collection methodology http://archaeologydataservice.ac.uk Planning Phase ACCORD project: Object-level and image documentation (multiple levels) If not specified during planning then unlikely (if not impossible) to get certain types and levels of metadata http://archaeologydataservice.ac.uk Ingest Ingest is where it all begins (for us): • Specify ingest file formats (limit diversity and future migration, ease metadata capture) • Aim to ingest as much metadata and contextual info as possible. -

News from the Past 2011 CBA West Midlands

I N T H I S ISSUE News from the Past 2011 CBA West Midlands Beneath I S S U E 1 1 WINTER 2010 Birmingham’s New Library Profiling Your Committee News from the Past 2011 Avoncroft Museum This year‟s News From the to modern times. into prehistoric Pedmore, the Building Rescue Past event takes place on Talks include news from archaeology of Redditch and Mick Aston on the February 26th 2011 in The excavations in Birmingham, the Northwick Project as Northwick Trail Library Theatre at Birming- Coventry and Martley, well as the remarkable Ro- ham Central Library and will Worcestershire, research man discoveries from Unearthing the Saltley Brick Industry highlight some of Kenchester and the year‟s most the newly discov- exciting archaeo- ered Villa at Bre- Find us on logical discover- dons Norton in Facebook! ies from across Worcestershire. the region. There will also be This annual an update from event includes the Conservators presentations working on the Search for CBA Caption describing picture West Midlands about sites and Staffordshire or graphic. objects from Hoard. rural and urban Booking details Visit our website at parts of the can be found on www.britarch.ac.uk/ region, ranging in the back page of cbawm date from prehistoric Part of the Staffordshire Saxon Hoard. Copyright this newsletter. Birmingham Museums & Art Gallery CBA West Midlands is a Registered Charity No. 512717 Beneath Birmingham’s New Library Excavations on the site of the mill were found as well as the and wire drawing machine new Library of Birmingham engine fly wheel pits, rolling bases, boiler flues and chim- revealed well-preserved ney, hearths and furnaces. -

Road, Winterbourne Dauntsey

MAIN ROAD, WINTERBOURNE DAUNTSEY Myddelton&Major Myddelton&Major An extraordinary opportunity to remodel and improve a substantial Grade II Listed detached thatched house with a detached brick-built one bedroom annex, formerly a telephone exchange. Description A classic English country home, with an abundance of charm including exposed brick, ceiling beams and pretty thatched roof. This attractive home offers an enormous amount of potential for any buyer looking to tailor a property to their own specification, subject to obtaining the relevant planning consents. All told, there are six bedrooms (one of which being the annex) and three bathrooms. A particular highlight is the sitting room; a very atmospheric room with a double aspect, a large inglenook fireplace and exposed ceiling beams. Beyond there is a double aspect dining room which in turn leads through to the kitchen, which has been extended to create an 18 ft kitchen/breakfast room that is ideal for entertaining. There is a separate utility room. Externally, there is a well-proportioned rear garden and a detached former telephone exchange which has been converted into a one bedroom property amounting to c.413 sq ft, with an open plan kitchen, bedroom and en suite. There is off road parking to the front and rear of the property as well as a two storage areas. Location Winterbourne Dauntsey, which interconnects with Winterbourne Earls and Winterbourne Gunner, has an excellent range of facilities including churches, primary school, nursery school, cricket club and public house. It is situated approximately three miles north of the Cathedral city of Salisbury, with all its excellent range of facilities including shopping, leisure, cultural and educational, along with the mainline train station to London Waterloo (journey time approximately 90 minutes). -

Honorary Graduates – 1966 - 2004

THE UNIVERSITY OF YORK HONORARY GRADUATES – 1966 - 2004 1966 MR PATRICK BLACKETT, physicist THE RT HON LORD GARDINER, Lord Chancellor SIR PETER HALL, director of plays and operas PRESIDENT KAUNDA, Head of State SIR HENRY MOORE, sculptor SIR ROBERT READ, poet and critic THE RT HON LORD ROBBINS, economist SIR MICHAEL TIPPETT, musician and composer THE RT HON BARONESS WOOTTON OF ABINGER 1967 SIR JOHN DUNNINGTON-JEFFERSON, for services to the University DR ARTHUR GLADWIN. For services to the University PROFESSOR F R LEAVIS, literary critic PROFESSOR WASSILY LEONTIEFF, economist PROFESSOR NIKLAUS PEVSNER, art & architecture critic and historian 1968 AMADEUS QUARTET NORBET BRAININ MARTIN LOVELL SIGMUND NISSELL PETER SCHIDLOF PROFESSOR F W BROOKS, historian LORD CLARK, art historian MRS B PAGE, librarian LORD SWANN, Biologist (and Director-General of the BBC) DAME EILEEN YOUNGHUSBAND, social administrator 1969 PROFESSOR L C KNIGHTS, literacy critic SIR PETER PEARS, singer SIR GEORGE PICKERING, scholar in medicine SIR GEORGE RUSSELL, industrial designer PROFESSOR FRANCIS WORMALD, historian 1969 Chancellor’s installation ceremony THE EARL OF CRAWFORD AND BALCARRES, patron of the arts MR JULIAN CAIN, scholar and librarian PROFESSOR DAVID KNOWLES, historian MR WALTER LIPPMAN, writer & journalist 1970 PROFESSOR ROGER BROWN, social psychologist THE RT HON THE VISCOUNT ESHER, PROFESSOR DOROTHY HODGKIN, chemist PROFESSOR A J P TAYLOR, historian 1971 DAME KITTY ANDERSON, headmistress DR AARON COPLAND, composer DR J FOSTER, secretary-General of the Association -

Old Oswestry HOOOH Newsletter

Issue 2 April 2014 O ur beautiful and world renowned hillfort, Old Oswestry, remains at risk. Fencers spar on the ramparts of old Oswestry hillfort Shropshire Council continues to which is still under threat of housing development close by. Photo courtesy of Richard Stonehouse support proposals that would see a significant part of its ancient green hinterland and archaeology blotted out by a large housing estate. In the face of fierce public opposition, the Council dropped two other “Countryside across England is being lost as a result of the housing schemes by the hillfort from Government’s planning policies, but the proposal to build over a hundred SAMDev, the County’s masterplan for houses in the setting of Old Oswestry Hillfort is notably philistine and development to 2026. But it is holding short-sighted. It is bad enough that the developer thinks this is an appropriate on to the largest with 117 houses, place to build; the fact that the Council is supporting the scheme beggars belief. called OSW004 (land off Whittington Of course we need to build more houses, particularly affordable houses, but it is Road), to meet five-year housing not necessary to trample on our history and despoil beautiful places to do so.” targets. Shaun Spiers, Chief Executive of CPRE, Campaign to Protect Rural England Construction by the hillfort would be fast-tracked to deliver twice the "Archaeological monuments such as hillforts like Old Oswestry cannot be number of houses by 2018 of any understood or appreciated if they are divorced from their landscape setting by other SAMDev site in Oswestry, its destruction through development. -

![Directory.] Wiltshire](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1218/directory-wiltshire-1351218.webp)

Directory.] Wiltshire

DIRECTORY.] WILTSHIRE. WINTERROURNE MONKTON. 261 Harris Rev. Henry B.D. Reetory \Horton James, fa.rmer, Rahson Redman James, farmer, Manor farm Godden John Stephen,White Horse inn Howell Harry, farmer, Whyr Scott W&.t-eT, shopkeeper WINTERBOURNE DANTSEY (or Dauntsey, or· Burtt, of the Manor House, is liady of the manor, and Middle Winterbourne ), is a village and parish, in the Mrs. King Wyndham and C. E. Clark esq. are chief 1Journe valley, 2 miles south-south-west from Porton landowners. The soil is chalk; subsoil, same. The station on the main line of the London and South chief crops are wheat, barley and roots. The area is WeSitern railway, 4 north-east from Salisbury and 5 1,143 acres; rateable value, £921; the population in 'SOUth-east frQm Amesbury, in the Southern division of 1891 was 136. the county, Alderbury hundred, Salisbury and Ames- Figsbury Ring (or Clorus's Camp) is 1 mile south· bury petty sessional diviSI:ion, Salisbury county court east. -district, Amesbury union, rural deanery of Amesbury (Alderbury portion), archdeaconry of Sarum and diocese Letters arrive from Salisbury at 6.30 a..m. & 3.Io p.m.; -of Salisbury. The church of the parish was taken down dispatched at 2 & 6.30 p.m. Tbs- nearest money an x867 a.nd the inhabitants attend that of Winterbourne order & telegraph office is at "\Vinterbourne Gunner Earls, to which parish this is annexed. Here is a The children of this parish attend the school at Winter- -chapel used by the Methooist New Connexion. Mrs. bourne EarlSJ Atkins Mrs. -

Winterbourne Gunner Marriages 1700-1799.Xlsx

Winterbourne Gunner Marriages 1700-1799 Year Date Groom Surname Groom Forename Bride Surname Bride Forename Notes 1703 29-Mar Phelps Ambrose Lawrence Ann 1703 20-Jul Gothard John Forth Ann Bride alias Taylor 1703 01-Dec Vince, Mr John Weitch Abigail Bride & Groom both of Salisbury 1704 20-Jun Smith Mathew Vine Jane 1710 21-Feb Harris Robert Joles Mary 1711 21-May Williams John Rose Suzanna 1712 05-Jul Hicks William MacKrell Ann 1713 25-May Brounson William Trignall Elizabeth 1713 19-Oct Rose John Martin Anne 1715 12-Nov Cooke Charles Brown Anne 1717 24-Dec Smith Charles Mowdy Catherine Groom of Salisbury. Bride of Homington 1717 15-Apr Smith Nicholas Witmarsh Dennis 1718 25-May Dounton Richard Thornton Mary 1719 25-Dec Maton Matthew Vine Mary Groom of Salisbury 1720 28-Apr Elliot John Hussey, Mrs Isabella 1721 27-May Philips William Vine Honor Groom of Clarendon Park 1721 27-Dec Young John Bodenham Esther Groom of Winton Hant. Bride wdw of Broad Chalk 1722 18-Nov Curtis Thomas Tinham Mary 1723 10-Nov Compton John Witmash Frances 1723 10-Jul Reeves William Thring Mary 1724 26-May Hayter Richard Hutfield Alies 1724 08-May Kill George Hayter Anne 1726 04-Sep White Thomas Forth Mary 1726 16-Oct Clark Thomas Baldwin Jane 1726 01-Nov Crook Robert Rose Ann 1727 26-Mar Tucker Thomas Short Mary 1731 20-Nov Arnold Edward Reeves Elizabeth Bride aka Susanna ? 1731 23-Nov Crook Robert Forth Martha Bride alias Taylor 1733 15-Sep London Richard Smart Mary 1733 05-Oct Witlock James Witmarsh Mary 1734 16-Jul Whitemaish William Forth Elizabeth Bride alias