The Sign and Seal of Justice

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cava of Toledo; Or, the Gothic Princess

Author: Augusta Amelia Stuart Title: Cava of Toledo; or, the Gothic Princess Place of publication: London Publisher: Printed at the Minerva-Press, for A. K. Newman and Co. Date of publication: 1812 Edition: 1st ed. Number of volumes: 5 CAVA OF TOLEDO. A ROMANCE. Lane, Darling, and Co. Leadenhall-Street. CAVA OF TOLEDO; OR, The Gothic Princess. A ROMANCE. IN FIVE VOLUMES BY AUGUSTA AMELIA STUART, AUTHOR OF LUDOVICO’S TALE; THE ENGLISH BROTHERS; EXILE OF PORTUGAL, &c. &c. Fierce wars, and faithful loves, And truths severe, in fairy fiction drest. VOL. I. LONDON: PRINTED AT THE Minerva Press, FOR A. K. NEWMAN AND CO. LEADENHALL-STREET. 1812. PREFACE. THE author of the following sheets, struck by the account historians have given of the fall of the Gothic empire in Spain, took the story of Cava for the foundation of a romance: whether she has succeeded or not in rendering it interesting, must be left to her readers to judge. She thinks it, however, necessary to say she has not falsified history; all relating to the war is exact: the real characters she has endeavoured to delineate such as they were; —Rodrigo—count Julian—don Palayo—Abdalesis, the Moor—queen Egilone—Musa—and Tariff, are drawn as the Spanish history represents them. Cava was never heard of from her quitting Spain with her father; of course, her adventures, from that period, are the coinage of the author’s brain. The enchanted palace, which Rodrigo broke into, is mentioned in history. Her fictitious characters she has moulded to her own will; and has found it a much more difficult task than she expected, to write an historical romance, and adhere to the truth, while she endeavoured to embellish it. -

CONGRESSIONAL RECORD— Extensions of Remarks E812 HON

E812 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — Extensions of Remarks March 30, 2009 Engine Repair Shop. The USS Tutuila func- of the Year by the United States Track & Field tion on Florida folk life while working for the tioned as a repair ship for the hundreds of and Cross Country Coaches Association WPA’s Federal Writers Project. As a result of small armed craft, or swift boats, used by the (USTFCCCA). her extensive anthropological research, her U.S. Navy and their South Vietnamese coun- Overall, the win marks SUNY Cortland’s writings have become invaluable sources on terparts in patrolling the numerous inland and 22nd national team title, including 16 NCAA African American life during the Harlem Ren- coastal waterways. Mr. Nissen and his fellow crowns in seven different sports. aissance. In all, Hurston wrote four novels and sailors worked around the clock to keep the Madam Speaker, I am honored to represent more than 50 published short stories, plays, swift boats functioning. They were often re- such skilled and hard-working athletes in my and essays, and she is best known for her sponsible for towing boats out of hostile areas district. Please join me in congratulating the 1937 novel ‘‘Their Eyes Were Watching God.’’ and transporting wounded sailors to safety. team and wishing them the best of luck in Madam Speaker, I would also like to recog- During his service on the USS Tutuila, Mr. their future athletic and scholarly pursuits. nize Dr. Gladys Pumariega Soler. Dr. Soler Nissen became interested in the work of the f was born in Cuba in 1930 and earned a med- medical staff and became a ‘‘striker’’ for a rat- ical degree from Havana University in 1955. -

Magazine in Our Next Issue: Azeri Women Making Bread

UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF STATE February 2003 StateMagazine In our next issue: Azeri women making bread. Baku Photo courtesy CLO State State Magazine (ISSN 1099–4165) is published monthly, except bimonthly in July and August, by the U.S. Department of State, Magazine 2201 C St., N.W., Washington, DC. Periodicals postage paid at Carl Goodman Washington, D.C., and at additional mailing locations. POSTMAS- EDITOR-IN-CHIEF TER: Send changes of address to State Magazine, HR/ER/SMG, Paul Koscak SA-1, Room H-236, Washington, DC 20522-0108. State Magazine WRITER/EDITOR is published to facilitate communication between management Dave Krecke and employees at home and abroad and to acquaint employees WRITER/EDITOR with developments that may affect operations or personnel. Deborah Clark The magazine is also available to persons interested in working DESIGNER for the Department of State and to the general public. State Magazine is available by subscription through the ADVISORY BOARD MEMBERS Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office, Florence Fultz Washington, DC 20402 (telephone [202] 512-1800) or on the web at CHAIR http://bookstore.gpo.gov. Jo Ellen Powell For details on submitting articles to State Magazine, request EXECUTIVE SECRETARY our guidelines, “Getting Your Story Told,” by e-mail at Sylvia Bazala [email protected]; download them from our web site Cynthia Bunton at www.state.gov/m/dghr/statemag;or send your request Bill Haugh in writing to State Magazine, HR/ER/SMG, SA-1, Room H-236, Bill Hudson Washington, DC 20522-0108. The magazine’s phone number is Jim Lawrence (202) 663-1700. -

America's Defense Meltdown

AMERICA’S DEFENSE MELTDOWN ★ ★ ★ Pentagon Reform for President Obama and the New Congress 13 non-partisan Pentagon insiders, retired military officers & defense specialists speak out The World Security Institute’s Center for Defense Information (CDI) provides expert analysis on various components of U.S. national security, international security and defense policy. CDI promotes wide-ranging discussion and debate on security issues such as nuclear weapons, space security, missile defense, small arms and military transformation. CDI is an independent monitor of the Pentagon and Armed Forces, conducting re- search and analyzing military spending, policies and weapon systems. It is comprised of retired senior government officials and former military officers, as well as experi- enced defense analysts. Funded exclusively by public donations and foundation grants, CDI does not seek or accept Pentagon money or military industry funding. CDI makes its military analyses available to Congress, the media and the public through a variety of services and publications, and also provides assistance to the federal government and armed services upon request. The views expressed in CDI publications are those of the authors. World Security Institute’s Center for Defense Information 1779 Massachusetts Avenue, NW Washington, D.C. 20036-2109 © 2008 Center for Defense Information ISBN-10: 1-932019-33-2 ISBN-13: 978-1-932019-33-9 America’s Defense Meltdown PENTAGON REFORM FOR PRESIDENT OBAMA AND THE NEW CONGRESS 13 non-partisan Pentagon insiders, retired military officers & defense specialists speak out Edited by Winslow T. Wheeler Washington, D.C. November 2008 ABOUT THE AUTHORS Thomas Christie began his career in the Department of Defense and related positions in 1955. -

H. Doc. 108-222

1776 Biographical Directory York for a fourteen-year term; died in Bronx, N.Y., Decem- R ber 23, 1974; interment in St. Joseph’s Cemetery, Hacken- sack, N.J. RABAUT, Louis Charles, a Representative from Michi- gan; born in Detroit, Mich., December 5, 1886; attended QUINN, Terence John, a Representative from New parochial schools; graduated from Detroit (Mich.) College, York; born in Albany, Albany County, N.Y., October 16, 1836; educated at a private school and the Boys’ Academy 1909; graduated from Detroit College of Law, 1912; admitted in his native city; early in life entered the brewery business to the bar in 1912 and commenced practice in Detroit; also with his father and subsequently became senior member engaged in the building business; delegate to the Democratic of the firm; at the outbreak of the Civil War was second National Conventions, 1936 and 1940; delegate to the Inter- lieutenant in Company B, Twenty-fifth Regiment, New York parliamentary Union at Oslo, Norway, 1939; elected as a State Militia Volunteers, which was ordered to the defense Democrat to the Seventy-fourth and to the five succeeding of Washington, D.C., in April 1861 and assigned to duty Congresses (January 3, 1935-January 3, 1947); unsuccessful at Arlington Heights; member of the common council of Al- candidate for reelection to the Eightieth Congress in 1946; bany 1869-1872; elected a member of the State assembly elected to the Eighty-first and to the six succeeding Con- in 1873; elected as a Democrat to the Forty-fifth Congress gresses (January 3, 1949-November 12, 1961); died on No- and served from March 4, 1877, until his death in Albany, vember 12, 1961, in Hamtramck, Mich; interment in Mount N.Y., June 18, 1878; interment in St. -

A Guide to the African American Heritage of Arlington County, Virginia

A GUIDE TO THE AFRICAN AMERICAN HERITAGE OF ARLINGTON COUNTY, VIRGINIA DEPARTMENT OF COMMUNITY PLANNING, HOUSING AND DEVELOPMENT HISTORIC PRESERVATION PROGRAM SECOND EDITION 2016 Front and back covers: Waud, Alfred R. "Freedman's Village, Greene Heights, Arlington, Virginia." Drawn in April 1864. Published in Harper's Weekly on May 7, 1864. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division. Table of Contents Discover Arlington's African American Heritage .......................... iii Lomax A.M.E. Zion Church & Cemetery .......................... 29 Mount Zion Baptist Church ................................................ 30 Boundary Markers of the District of Columbia ............................ 1 Macedonia Baptist Church ................................................. 31 Benjamin Banneker ............................................................. 1 Our Lady, Queen of Peace Catholic Church .................... 31 Banneker Boundary Stone ................................................. 1 Establishment of the Kemper School ............................... 32 Principal Ella M. Boston ...................................................... 33 Arlington House .................................................................................. 2 Kemper Annex and Drew Elementary School ................. 33 George Washington Parke Custis ...................................... 2 Integration of the Drew School .......................................... 33 Custis Family and Slavery ................................................... 2 Head -

Charles Spaak and the Thesis Film Geoffrey Wagner

New Mexico Quarterly Volume 24 | Issue 2 Article 10 1954 Charles Spaak and the Thesis Film Geoffrey Wagner Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/nmq Recommended Citation Wagner, Geoffrey. "Charles Spaak and the Thesis Film." New Mexico Quarterly 24, 2 (1954). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/nmq/ vol24/iss2/10 This Contents is brought to you for free and open access by the University of New Mexico Press at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in New Mexico Quarterly by an authorized editor of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Wagner: Charles Spaak and the Thesis Film BOOKS and COMMENT Geoffrey Wagner CHARLES SPAAK AND THE THESIS FILM HET RIC 0 LOR waves over the Palais de Justice. Three words are engraved on the ancient stone: LIBERTt T;EGALITt-FRATERNITt. The camera drops a frac tion. We see a harshly modern enamel plate-Place d'Arret. This shot from Avant Ie deluge, written and co-directed by Charles Spaak, bespeaks the thesis, with all its attendant over simplifications, of one of the most provocative screen writers working today-namely, that we are all assassins and that justice is never done. While the cinema in this country is suffering from an overdose of skill-fetichism (one technical gimmick after an other vainly trying to make up. for an emptiness of soul) , and while the Italian realist film is proving steadily more inelastic, Spaak is quietly proceeding with the serious business of the cin ema, enlarging it "in depth" by lending it that most unlikely di mension, real intellectual fervor. -

Fellows of the Royal Society 1660 – 2007

Library and Information Services List of Fellows of the Royal Society 1660 – 2007 K - Z Library and Information Services List of Fellows of the Royal Society 1660 - 2007 A complete listing of all Fellows and Foreign Members since the foundation of the Society K - Z July 2007 List of Fellows of the Royal Society 1660 - 2007 The list contains the name, dates of birth and death (where known), membership type and date of election for all Fellows of the Royal Society since 1660, including the most recently elected Fellows (details correct at July 2007) and provides a quick reference to around 8,000 Fellows. It is produced from the Sackler Archive Resource, a biographical database of Fellows of the Royal Society since its foundation in 1660. Generously funded by Dr Raymond R Sackler, Hon KBE, and Mrs Beverly Sackler, the Resource offers access to information on all Fellows of the Royal Society since the seventeenth century, from key characters in the evolution of science to fascinating lesser- known figures. In addition to the information presented in this list, records include details of a Fellow’s education, career, participation in the Royal Society and membership of other societies. Citations and proposers have been transcribed from election certificates and added to the online archive catalogue and digital images of the certificates have been attached to the catalogue records. This list is also available in electronic form via the Library pages of the Royal Society web site: www.royalsoc.ac.uk/library Contributions of biographical details on any Fellow would be most welcome. -

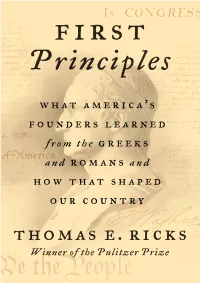

First Principles of Polite Learning Are Laid Down in a Way Most Suitable for Trying the Genius, and Advancing the Instruc�On of Youth

Dedicaon For the dissenters, who conceived this naon, and improve it sll Epigraph Unless we can return a lile more to first principles, & act a lile more upon patrioc ground, I do not know . what may be the issue of the contest. —George Washington to James Warren, March 31, 1779 Contents Cover Title Page Dedicaon Epigraph A Note on Language Chronology Map Prologue Part I: Acquision Chapter 1: The Power of Colonial Classicism Chapter 2: Washington Studies How to Rise in Colonial Society Chapter 3: John Adams Aims to Become an American Cicero Chapter 4: Jefferson Blooms at William & Mary Chapter 5: Madison Breaks Away to Princeton Part II: Applicaon Chapter 6: Adams and the Fuse of Rebellion Chapter 7: Jefferson’s Declaraon of the “American Mind” Chapter 8: Washington Chapter 9: The War Strains the Classical Model Chapter 10: From a Difficult War to an Uneasy Peace Chapter 11: Madison and the Constuon Part III: Americanizaon Chapter 12: The Classical Vision Smashes into American Reality Chapter 13: The Revoluon of 1800 Chapter 14: The End of American Classicism Epilogue Acknowledgments Appendix: The Declaraon of Independence Notes Index About the Author Also by Thomas E. Ricks Copyright About the Publisher A Note on Language I have quoted the words of the Revoluonary generaon as faithfully as possible, including their unusual spellings and surprising capitalizaons. I did this because I think it puts us nearer their world, and also out of respect: I wouldn’t change their words when quong them, so why change their spellings? For some reason, I am fond of George Washington’s apoplecc denunciaon of an “ananominous” leer wrien by a munous officer during the Revoluonary War. -

Medical Heritage of the National Palace of Mafra

Medical Heritage of the National Palace of Mafra Medical Heritage of the National Palace of Mafra Edited by Maria do Sameiro Barroso, Christopher J. Duffin and Germano de Sousa Medical Heritage of the National Palace of Mafra Edited by Maria do Sameiro Barroso, Christopher J. Duffin and Germano de Sousa This book first published 2020 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2020 by Maria do Sameiro Barroso, Christopher J. Duffin, Germano de Sousa and contributors All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-5275-4426-5 ISBN (13): 978-1-5275-4426-0 TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Illustrations ................................................................................... vii Introduction ................................................................................................ 1 Christopher J. Duffin and Maria do Sameiro Barroso Chapter 1 .................................................................................................... 9 The National Palace of Mafra and King John V – some historical and medical insights António Trabulo Chapter 2 ................................................................................................. -

The Rise of Cornelius Peter Van Ness 1782- 18 26

PVHS Proceedings of the Vermont Historical Society 1942 NEW SERIES' MARCH VOL. X No. I THE RISE OF CORNELIUS PETER VAN NESS 1782- 18 26 By T. D. SEYMOUR BASSETT Cornelius Peter Van Ness was a colorful and vigorous leader in a formative period of Vermont history, hut he has remained in the dusk of that history. In this paper Mr. Bassett has sought to recall __ mm and IUs activities and through him throw definite light on h4s --------- eventfultime.l.- -In--this--study Van--N-esr--ir-brought;-w--rlre-dt:a.mot~ months of his attempt in the senatorial election of I826 to succeed Horatio Seymour. 'Ulhen Mr. Bassett has completed his research into thot phase of the career of Van Ness, we hope to present the re sults in another paper. Further comment will he found in the Post script. Editor. NDIVIDUALISM is the boasted virtue of Vermonters. If they I are right in their boast, biographies of typical Vermonters should re veal what individualism has produced. Governor Van Ness was a typical Vermonter of the late nineteenth century, but out of harmony with the Vermont spirit of his day. This essay sketches his meteoric career in administrative, legislative and judicial office, and his control of Vermont federal and state patronage for a decade up to the turning point of his career, the senatorial campaign of 1826.1 His family had come to N ew York in the seventeenth century. 2 His father was by trade a wheelwright, strong-willed, with little book-learning. A Revolutionary colonel and a county judge, his purchase of Lindenwald, an estate at Kinderhook, twenty miles down the Hudson from Albany, marked his social and pecuniary success.s Cornelius was born at Lindenwald on January 26, 1782. -

Illinois Congressional Delegation Bios

Illinois Congressional Delegation Bios Senator Richard Durbin (D-IL) Senator Dick Durbin, a Democrat from Springfield, is the 47th U.S. Senator from the State of Illinois, the state’s senior senator, and the convener of Illinois’ bipartisan congressional delegation. Durbin also serves as the Assistant Democratic Leader, the second highest ranking position among the Senate Democrats. Also known as the Minority Whip, Senator Durbin has been elected to this leadership post by his Democratic colleagues every two years since 2005. Elected to the U.S. Senate on November 5, 1996, and re-elected in 2002, 2008, and 2014, Durbin fills the seat left vacant by the retirement of his long-time friend and mentor, U.S. Senator Paul Simon. Durbin sits on the Senate Judiciary, Appropriations, and Rules Committees. He is the Ranking Member of the Judiciary Committee's Subcommittee on the Constitution and the Appropriations Committee's Defense Subcommittee. Senator Tammy Duckworth (D-IL) U.S. Senator Tammy Duckworth is an Iraq War Veteran, Purple Heart recipient and former Assistant Secretary of the Department of Veterans Affairs. She was among the first Army women to fly combat missions during Operation Iraqi Freedom. Duckworth served in the Reserve Forces for 23 years before retiring from military service in 2014 at the rank of Lieutenant Colonel. She was elected to the U.S. Senate in 2016 after representing Illinois’s Eighth Congressional District in the U.S. House of Representatives for two terms. In 2004, Duckworth was deployed to Iraq as a Black Hawk helicopter pilot for the Illinois Army National Guard.