BACKSTRAW by Tom Ball

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Othered Intellectual in Joyce and Ellison Will Simonson Bucknell University, [email protected]

Bucknell University Bucknell Digital Commons Honors Theses Student Theses Spring 2018 An Ivory Tower on the Outskirts of Town: The Othered Intellectual in Joyce and Ellison Will Simonson Bucknell University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.bucknell.edu/honors_theses Part of the Literature in English, British Isles Commons, and the Literature in English, North America, Ethnic and Cultural Minority Commons Recommended Citation Simonson, Will, "An Ivory Tower on the Outskirts of Town: The Othered Intellectual in Joyce and Ellison" (2018). Honors Theses. 437. https://digitalcommons.bucknell.edu/honors_theses/437 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Theses at Bucknell Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Bucknell Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. iv Acknowledgements First and foremost, I wish to acknowledge my thesis director, Professor Anthony Stewart, without whom this thesis would likely not have begun, much less been completed. I am eternally grateful for the countless hours spent in your office this year, those spent on this project and all the others. For your guidance, mentorship, and encouragement, I am truly indebted. I wish to thank Professor Raphael Dalleo, for agreeing to serve as my Second Reader, Professor Fernando Blanco, for taking an interest in this project and becoming a part of it, and Professor Saundra Morris, for meticulous editing and thoughtful feedback, as well as invaluable assistance in navigating this endeavor. Thank you also to the English Graduate students for reading so many early drafts and tirelessly making my work better. -

2020 Musical Event of the Year “Fooled Around and Fell in Love” (Feat

FOR YOUR CMA CONSIDERATION ENTERTAINER OF THE YEAR FEMALE VOCALIST OF THE YEAR SINGLE OF THE YEAR SONG OF THE YEAR MUSIC VIDEO OF THE YEAR “BLUEBIRD” #1 COUNTRY RADIO AIRPLAY HIT OVER 200 MILLION GLOBAL STREAMS ALBUM OF THE YEAR WILDCARD #1 TOP COUNTRY ALBUMS DEBUT THE BIGGEST FEMALE COUNTRY ALBUM DEBUT OF 2019 & 2020 MUSICAL EVENT OF THE YEAR “FOOLED AROUND AND FELL IN LOVE” (FEAT. MAREN MORRIS, ELLE KING, ASHLEY MCBRYDE, TENILLE TOWNES & CAYLEE HAMMACK) “We could argue [Lambert’s] has been the most important country music career of the 21st century” – © 2020 Sony Music Entertainment ENTERTAINER ERIC CHURCH “In a Music Row universe where it’s always about the next big thing – the hottest new pop star to collaborate with, the shiniest producer, the most current songwriters – Church is explicitly focused on his core group and never caving to trends or the fleeting fad of the moment.” –Marissa Moss LUKE COMBS “A bona fide country music superstar.” –Rolling Stone “Let’s face it. Right now, it’s Combs’ world, and we just live in it.” –Billboard “Luke Combs is the rare exception who exploded onto the scene, had a better year than almost anyone else in country music, and is only getting more and more popular with every new song he shares.” –Forbes MIRANDA LAMBERT “The most riveting country star of her generation.” –NPR “We could argue [Lambert’s] has been the most important country music career of the 21st century.” –Variety “One of few things mainstream-country-heads and music critics seem to agree on: Miranda Lambert rules.” –Nashville Scene “The queen of modern country.” –Uproxx “.. -

Wavelength (September 1986)

University of New Orleans ScholarWorks@UNO Wavelength Midlo Center for New Orleans Studies 9-1986 Wavelength (September 1986) Connie Atkinson University of New Orleans Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uno.edu/wavelength Recommended Citation Wavelength (September 1986) 71 https://scholarworks.uno.edu/wavelength/62 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Midlo Center for New Orleans Studies at ScholarWorks@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Wavelength by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NS SIC MAGA u........s......... ..AID lteniiH .... ., • ' lw•~.MI-- "I'm not sure, but I'm almost positive, that all music came from New Orleans." -Ernie K-Doe, 1979 Features The Party ... .... .. .. ... 21 The Faith . .... .. ....... 23 The Saints . .... .... .. 24 Departments September News ... ... .. 4 Latin ... ... .. ..... .. 8 Chomp Report ...... .. .. 10 Caribbean . .. .. ......... 12 Rock ........ ... ........ 14 Comedy ... ... .... .. ... 16 U.S. Indies .. .. ... .. ... 18 September Listings ... ... 29 Classifieds ..... ..... 33 Last Page . .. .. .... .... 34 Cover Art by Bunny MaHhews A1mlbzrot NetWCSfk Pubaidwr ~ N.. un~.,~n S ~·ou F:ditor. Cnnn~ /..c;rn.ih Atk 1 n~ Assonat• FAI1lor. (it.:n..: S4.at.&mU/It) Art Dindor. Thom~... Oul.an Ad,mL-Jn •. Fht.ah.:th hlf1l.J•~ - 1>1.:.tn.a N.M.l~'-' COft· tributon, Sl(\\.' Armf,ru,tcr. St (M.."tlfl!C Hry.&n. 0..-t> C.n.Jh4:llll, R1d. Culcnun. Carul Gn1ad) . (iu'U GUl'uuo('. Lynn H.arty. P.-t Jully. J.mlC' l.k:n, Bunny M .anhc~'· M. 11.k Oltvter. H.1mmnnd ~·,teL IAlm: Sll'l"t:l. -

Artist with Title Writer Label Cat Year Genre

Artist With Title Writer Label Cat Year Genre Notes Album Synopsis_c Anonymous Uncle Tom’s Cabin No Label 0 Comedy Anonymous - Uncle Tom’s Cabin, No Label , 78, ???? Anonymous The Secretary No Label 0 Comedy Anonymous - The Secretary, No Label , 78, ???? Anonymous Mr. Speaker No Label 0 Comedy Anonymous - Mr. Speaker, No Label , 78, ???? Anonymous The Deacon No Label 0 Comedy Anonymous - The Deacon, No Label , 78, ???? Anonymous First Swimming Lesson Good-Humor 10 0 Comedy Anonymous - First Swimming Lesson, Good-Humor 10, 78, ???? Anonymous Auto Ride Good-Humor 4 0 Comedy Anonymous - Auto Ride, Good-Humor 4, 78, ???? Anonymous Pioneer XXX, Part 1 No Label 0 Comedy Anonymous - Pioneer XXX, Part 1, No Label , 78, ???? Anonymous Pioneer XXX, Part 2 No Label 0 Comedy Anonymous - Pioneer XXX, Part 2, No Label , 78, ???? Anonymous Instrumental w/ lots of reverb No Label 0 R&B Anonymous - Instrumental w/ lots of reverb, No Label , 78, ???? Coy and Helen Tolbert There’s A Light Guiding Me Chapel Tone 775 0 Gospel with Guitar Coy and Helen Tolbert - There’s A Light Guiding Me, Chapel Tone 775, 78, ???? Coy and Helen Tolbert Old Camp Meeting Days R. E. Winsett Chapel Tone 775 0 Gospel with Guitar Coy and Helen Tolbert - Old Camp Meeting Days (R. E. Winsett), Chapel Tone 775, 78, ???? Donna Lane and Jack Milton Henry Brandon And His Orchestra Love On A Greyhound Bus Blane - Thompson - Stoll Imperial 1001 0 Vocal Donna Lane and Jack Milton - Love On A Greyhound Bus (Blane - Thompson - Stoll), Imperial 1001, 78, ???? G. M. Farley The Works Of The Lord Rural Rhythm 45-EP-551 0 Country G. -

Donaldson, Your Full Name and Your Parents’ Names, Your Mother and Father

Funding for the Smithsonian Jazz Oral History Program NEA Jazz Master interview was provided by the National Endowment for the Arts. LOU DONALDSON NEA Jazz Master (2012) Interviewee: Louis Andrew “Lou” Donaldson (November 1, 1926- ) Interviewer: Ted Panken with recording engineer Ken Kimery Dates: June 20 and 21, 2012 Depository: Archives Center, National Music of American History, Description: Transcript. 82 pp. [June 20th, PART 1, TRACK 1] Panken: I’m Ted Panken. It’s June 20, 2012, and it’s day one of an interview with Lou Donaldson for the Smithsonian Institution Oral History Jazz Project. I’d like to start by putting on the record, Mr. Donaldson, your full name and your parents’ names, your mother and father. Donaldson: Yeah. Louis Andrew Donaldson, Jr. My father, Louis Andrew Donaldson, Sr. My mother was Lucy Wallace Donaldson. Panken: You grew up in Badin, North Carolina? Donaldson: Badin. That’s right. Badin, North Carolina. Panken: What kind of town is it? Donaldson: It’s a town where they had nothing but the Alcoa Aluminum plant. Everybody in that town, unless they were doctors or lawyers or teachers or something, worked in the plant. Panken: So it was a company town. Donaldson: Company town. For additional information contact the Archives Center at 202.633.3270 or [email protected] Page | 1 Panken: Were you parents from there, or had they migrated there? Donaldson: No-no. They migrated. Panken: Where were they from? Donaldson: My mother was from Virginia. My father was from Tennessee. But he came to North Carolina to go to college. -

Auto Biography: a Daughter's Story Told in Cars

University of New Orleans ScholarWorks@UNO University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations Dissertations and Theses 5-20-2005 Auto Biography: A Daughter's Story Told in Cars Lynda Routledge Stephenson University of New Orleans Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td Recommended Citation Stephenson, Lynda Routledge, "Auto Biography: A Daughter's Story Told in Cars" (2005). University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations. 231. https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td/231 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by ScholarWorks@UNO with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights- holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. AUTO BIOGRAPHY A DAUGHTER'S STORY TOLD IN CARS A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the University of New Orleans in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts in Drama and Communications Creative Writing by Lynda Rutledge Stephenson B.A. Baylor University, 1972 M.A. Texas Tech University, 1981 May 2005 © 2005, Lynda Rutledge Stephenson ii To my sisters, who have their own tales to tell iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract ..........................................................................................................................v Epigraphs ..................................................................................................................... -

Turtle Rock Guitar Book 5.Pdf

Preface to the 5th Edition This book and the Guitar Club that went with it started because one of my old counsellors put a few guitar chords into the official camp song book. Those chords were the reason I learned to play. That summer, when we were last-year campers, regular activities were cancelled one day because of stormy weather. We all piled into the lodge, where we sat with Ryley and her guitar, singing all afternoon. It was the first time a lot of us had ever sung our favourite camp songs with a guitar. At the time, I'd never even heard recordings of most of them. (This is before Napster, kids.) I remain ever thankful that we didn't play Rainy Day Bingo that afternoon. At the end of the summer I started writing in chords for the rest of the song book, which gradually led to the first edition of The Mi-A-Kon-Da Guitar Book. Since then, this book's seen a few new places and met a lot of new songs. It seemed about time to give it a name that would bring everything and everyone together. Turtle Rock does just this. On Birch Island, it's where the whole camp meets after lights out on Mi-A-Kon-Da night to sing quiet songs by the fire, listen to the camp legend, and watch the full moon rise over the lake. It's also where we meet for special cook-outs, reflections, and early in the morning to watch that bittersweet Last Sunrise of the Summer. -

Billboard Charted Albums.Xlsx

DEBUT PEAK WKS RIAAFORMAT TITLE LABEL SEL# ABOUT A MILE 8/2/14 20 14 Christian 1. About A Mile/ 8/2/14 11 7 Heatseek About A Mile Curb-Word ACUFF, Roy 4/6/74 44 6 Country 1. Back In The Country Hickory/MGM 4507 ADAMS, Kay 5/14/66 16 12 Country 1. A Devil Like Me Needs An Angel Like You (w/ Dick Curless) Tower/Sidewalk 5025 11/19/66 36 5 Country 2. Wheels & Tears Tower/Sidewalk 5033 ADAMS, Yolanda (7) 12/22/01 2 67 l Christian 1. Believe Elektra/Curb-Word 62690 ADKINS, Wendel 3/12/77 46 5 Country 1. Sundowners Hitsville 406 ALLAN, Davie, And The Arrows 10/15/66 17 71 Top200 1. The Wild Angels Tower/Sidewalk 5043 4/22/67 94 18 Top200 2. The Wild Angels, Vol. II Tower/Sidewalk 5056 8/19/67 165 2 Top200 3. Devil's Angels Tower/Sidewalk 5074 all of above produced by Mike Curb ALLANSON, Susie 8/26/78 42 4 Country 1. We Belong Together Warner/Curb 3217 4/28/79 11 15 Country 2. Heart To Heart Elektra/Curb 177 AMERICAN YOUNG 7/19/14 39 1 Country 1. American Young (EP)/ 7/19/14 12 1 Heatseek American Young (EP) Curb ANDERSON, Bill 3/30/91 64 4 Country 1. Best Of Bill Anderson Curb 77436 ANDREWS, Meredith 5/17/08 19 4 Christian 1. The Invitation Curb-Word 87410 3/20/10 12 6 Christian 2. As Long As It Takes/ 3/20/10 5 3 HeatSeek As Long As It Takes Curb-Word 87950 2/9/13 7 7 Christian 3. -

Dox Thrash: Revealed a Companion Site to the Philadelphia Museum of Art Exhibit: Dox Thrash: an African American Master Printmaker Rediscovered 1893-1907

Dox Thrash: Revealed a companion site to the Philadelphia Museum of Art exhibit: Dox Thrash: An African American Master Printmaker Rediscovered 1893-1907 Prelude “The sky, lazily disdaining to pursue The setting sun, too indolent to hold A lengthened tournament for flashing gold, Passively darkens for night’s barbecue.” Jean Toomer-Georgia Dusk In His Own Words “I liked to draw… also adventure in the woods mostly by myself. I was especially fond of kites and swim- ming. As an older boy, I did not have much schooling, but I learned what education I have from reading books, listening to conversation and traveling.” The Thrash Family Dox Thrash is born to Gus and Ophelia Thrash in Griffin Georgia, a small town in Spalding County. Dox is the second of four children, brother Tennessee, Cabin Days c. 1938–39, carborundum mezzotint, 9 15⁄16 x 9 1⁄8 inches (25.3 x 23.1 cm). Philadelphia Museum of Art, purchased with the Thomas Skelton Harrison Fund. and sisters Agnes (Gussie) and Margaret Elinor. The Thrash family live on the outskirts of town in a former slave cabin built on a small rise of land overlooking the road running north to Atlanta. Ophelia Thrash Dox Thrash’s mother Ophelia Thrash is cook-house- keeper for a white family in Griffin named Taylor. She works every day of the week except on Sunday, when she only cooked breakfast. In the evenings, Mrs. Taylor often drives Mrs. Thrash home with food for her own family’s table. The seven-day schedule and provision of food is common practice for domestic Sunday Morning workers in Georgia at the time. -

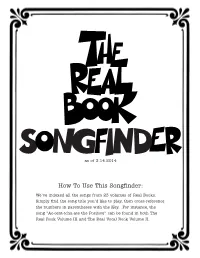

How to Use This Songfinder

as of 3.14.2014 How To Use This Songfinder: We’ve indexed all the songs from 23 volumes of Real Books. Simply find the song title you’d like to play, then cross-reference the numbers in parentheses with the Key. For instance, the song “Ac-cent-tchu-ate the Positive” can be found in both The Real Book Volume III and The Real Vocal Book Volume II. KEY Unless otherwise marked, books are for C instruments. For more product details, please visit www.halleonard.com/realbook. 01. The Real Book – Volume I 08. The Real Blues Book/00240264 C Instruments/00240221 09. Miles Davis Real Book/00240137 B Instruments/00240224 Eb Instruments/00240225 10. The Charlie Parker Real Book/00240358 BCb Instruments/00240226 11. The Duke Ellington Real Book/00240235 Mini C Instruments/00240292 12. The Bud Powell Real Book/00240331 Mini B Instruments/00240339 CD-ROMb C Instruments/00451087 13. The Real Christmas Book C Instruments with Play-Along Tracks C Instruments/00240306 Flash Drive/00110604 B Instruments/00240345 Eb Instruments/00240346 02. The Real Book – Volume II BCb Instruments/00240347 C Instruments/00240222 B Instruments/00240227 14. The Real Rock Book/00240313 Eb Instruments/00240228 15. The Real Rock Book – Volume II/00240323 BCb Instruments/00240229 16. The Real Tab Book – Volume I/00240359 Mini C Instruments/00240293 CD-ROM C Instruments/00451088 17. The Real Bluegrass Book/00310910 03. The Real Book – Volume III 18. The Real Dixieland Book/00240355 C Instruments/00240233 19. The Real Latin Book/00240348 B Instruments/00240284 20. The Real Worship Book/00240317 Eb Instruments/00240285 BCb Instruments/00240286 21. -

Curb Label Discography by David Edwards, Mike Callahan & Patrice Eyries © 2018 by Mike Callahan Curb Label Discography

Curb Label Discography by David Edwards, Mike Callahan & Patrice Eyries © 2018 by Mike Callahan Curb Label Discography Curb Label Distributed by RCA RCA/Curb AHL/PCD 1 5319 — Why Not Me — The Judds [1984] Why Not Me/Mr. Pain/Drops Of Water/Sleeping Heart/My Baby's Gone/Bye Bye Baby Blues/Girls Night Out/Love Is Alive/Endless Sleep/Mama He's Crazy *AHL1-7042 — Rockin’ With The Rhythm — The Judds [1985] Cry Myself To Sleep/Dream Chaser/Grandpa (Tell Me ‘Bout The Good Old Days)/Have Mercy/I Wish She Wouldn’t Treat You That Way/If I Were You/River Roll On/Rockin’ With The Rhythm Of The Rain/Tears For You/Working In The Coal Mine *MHL 1-8515 — The Judds — The Judds [1984] Blue Nun Cafe/Change Of Heart/Had A Dream (For The Heart)/Isn’t He A Strange One/John Deere Tractor/Mama He’s Crazy 2070-1 R — Love Can Build A Bridge — The Judds [1990] Are The Roses Not Blooming/Born To Be Blue/Calling In The Wind/In My Dreams/John Deere Tractor/Love Can Build A Bridge/One Hundred And Two/Rompin’ Stompin’ Blues/Talk About Love • This Country’s Rockin’ RCA/Curb Victor 5916 1R — Heartland — The Judds [1987] Don’t Be Cruel/I’m Falling In Love Tonight/Turn It Loose/Old Pictures/Cow Cow Boogie/Maybe Your Baby’s Got The Blues/I Know Where I’m Going/Why Don’t You Believe Me/The Sweetest Gift *6422-1 R — Christmas Time With The Judds — The Judds [1987] Away In A Manger/Beautiful Star Of Bethlehem/Oh Holy Night/Santa Claus Is Comin’ To Town/Silent Night/Silver Bells/What Child Is This/Who Is This Babe/Winter Wonderland *8318-1 R — Greatest Hits — The Judds [1988] Change Of Heart/Cry Myself To Sleep/Girls Night Out/Give A Little Love/Grandpa (Tell Me ‘Bout The Good Old Days)/Have Mercy/Love Is Alive/Rockin’ With The Rhythm Of The Rain/Why Not Me 9595-1 R — River Of Time — The Judds [1989] Cadillac Red/Guardian Angel/Let Me Tell You About Love/Not My Baby/One Man Woman/River Of Time/Sleepless Nights/Water Of Love/Young Love Curb Label Distributed by Elektra Elektra E 100 Series *Elektra-Curb 6E 194 - Family Tradition - Hank Williams Jr. -

Album and Studio Notes

Album and Studio Notes BILL AND SUE-ON HILLMAN A 50-YEAR MUSICAL ODYSSEY www.hillmanweb.com/book Presents ALBUM AND STUDIO TALK Visit the Album pages for credits, photos, anecdotes, lyrics, reviews, and the actual recordings in MP3 files. HILLMAN ALBUM WALL CONTENTS www.hillmanweb.com/albums CONTENTS FOR THIS ALBUM NOTES PAGE www.hillmanweb.com/albums/notes.html PDF VERSION ONE TWO THREE FOUR FIVE SIX SEVEN EIGHT NINE CDs BILL AND SUE-ON HILLMAN RECORD ALBUM #1 THE WESTERN UNION I: Galaxy Records ~ GSLP 1012 ~ 1969-70 Bill and Sue-On Hillman ~ Barry Forman ~ Jake Kroeger ALBUM 1: Credits ~ Photos ~ Anecdotes ~ Lyrics ~ Reviews ~ MP3 Files www.hillmanweb.com/albums/album01.html BEHIND THE SCENES By late 1969 we had pretty much touched all show biz bases: bars, concerts, tours, TV & Radio, exhibitions media coverage, etc. The logical progression now seemed to be to get something on record. This was a very difficult undertaking at that time as there were no professional studios in the area. Nor was there anyone who knew anything about getting original songs published, record production, manufacture, distribution, promotion, etc. In our search for contacts we found that about the only records being produced in Manitoba were ethnic (largely Ukrainian) and gospel. Enter Alex Moodrey, who had produced and distributed a number of Ukainian music albums on his Winnipeg label, Galaxy Records. The deal we made with Alex was that he would record us in his studio, pay for the pressing and jackets, and would then have rights to our album which he would distribute through his network of shops selling Ukrainian and ethnic music - which included stores in Chicago, of all places.