Canada's Unresolved Maritime Boundaries

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Alaska Boundary Dispute

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository University of Calgary Press University of Calgary Press Open Access Books 2014 A historical and legal study of sovereignty in the Canadian north : terrestrial sovereignty, 1870–1939 Smith, Gordon W. University of Calgary Press "A historical and legal study of sovereignty in the Canadian north : terrestrial sovereignty, 1870–1939", Gordon W. Smith; edited by P. Whitney Lackenbauer. University of Calgary Press, Calgary, Alberta, 2014 http://hdl.handle.net/1880/50251 book http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Attribution Non-Commercial No Derivatives 4.0 International Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca A HISTORICAL AND LEGAL STUDY OF SOVEREIGNTY IN THE CANADIAN NORTH: TERRESTRIAL SOVEREIGNTY, 1870–1939 By Gordon W. Smith, Edited by P. Whitney Lackenbauer ISBN 978-1-55238-774-0 THIS BOOK IS AN OPEN ACCESS E-BOOK. It is an electronic version of a book that can be purchased in physical form through any bookseller or on-line retailer, or from our distributors. Please support this open access publication by requesting that your university purchase a print copy of this book, or by purchasing a copy yourself. If you have any questions, please contact us at ucpress@ ucalgary.ca Cover Art: The artwork on the cover of this book is not open access and falls under traditional copyright provisions; it cannot be reproduced in any way without written permission of the artists and their agents. The cover can be displayed as a complete cover image for the purposes of publicizing this work, but the artwork cannot be extracted from the context of the cover of this specificwork without breaching the artist’s copyright. -

Conservation Prioritization of Prince of Wales Island

CONSERVATION PRIORITIZATION OF PRINCE OF WALES ISLAND Identifying opportunities for private land conservation Prepared by the Southeast Alaska Land Trust With support from U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Southeast Alaska Coastal Conservation Program February 2013 Conservation prioritization of Prince of Wales Island Conservation prioritization of Prince of Wales Island IDENTIFYING OPPORTUNITIES FOR PRIVATE LAND CONSERVATION INTRODUCTION The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) awarded the Southeast Alaska Land Trust (SEAL Trust) a Coastal Grant in 2012. SEAL Trust requested this grant to fund a conservation priority analysis of private property on Prince of Wales Island. This report and an associated Geographic Information Systems (GIS) map are the products of that work. Driving SEAL Trust’s interest in conservation opportunities on Prince of Wales Island is its obligations as an in-lieu fee sponsor for Southeast Alaska, which makes it eligible to receive fees in-lieu of mitigation for wetland impacts. Under its instrument with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers1, SEAL Trust must give priority to project sites within the same 8-digit Hydrologic Unit (HUC) as the permitted impacts. In the past 10 years, SEAL Trust has received a number of in-lieu fees from wetlands impacted by development on Prince of Wales Island, which, along with its outer islands, is the 8-digit HUC #19010103 (see Map 1). SEAL Trust has no conservation holdings or potential projects on Prince of Wales Island. In an attempt to achieve its conservation goals and compliance with the geographic elements of the Instrument, SEAL Trust wanted to take a strategic approach to exploring preservation possibilities in the Prince of Wales HUC. -

Why Does Canada Have So Many Unresolved Maritime Boundary Disputes? –– Pourquoi Le Canada A-T-Il Autant De Différends Non Résolus Concernant Ses Frontières Maritimes?

Why Does Canada Have So Many Unresolved Maritime Boundary Disputes? –– Pourquoi le Canada a-t-il autant de différends non résolus concernant ses frontières maritimes? michael byers and andreas Østhagen Abstract Résumé Canada has five unresolved maritime Le Canada a cinq frontières maritimes qui boundaries. This might seem like a high n’ont pas encore été délimitées. Ce nom- number, given that Canada has only three bre peut paraitre élevé étant donné que le neighbours: the United States, Denmark Canada n’a que trois voisins: les États-Unis, (Greenland), and France (St. Pierre and le Danemark (Groënland) et la France (St. Miquelon). This article explores why Pierre et Miquelon). Cet article cherche à Canada has so many unresolved maritime découvrir pourquoi le Canada a tant de boundaries. It does so through a compar- frontières maritimes irrésolues. Pour ce ison with Norway, which has settled all of faire, l’article se penche sur le cas de la its maritime boundaries, most notably in Norvège, qui a réussi à délimiter toutes ses the Barents Sea with Russia. This compar- frontières maritimes, y compris dans la mer ison illuminates some of the factors that de Barents avec la Russie. Cette comparai- motivate or impede maritime boundary son met en relief certains des facteurs qui negotiations. It turns out that the status favorisent ou entravent les négociations of each maritime boundary can only be pour la résolution de différends maritimes explained on the basis of its own unique frontaliers. Il s’avère que le statut des fron- geographic, historic, political, and legal tières maritimes ne peut s’expliquer qu’en context. -

Cole, Douglas. Sigismund Bacstrom's Northwest Coast Drawings and An

Sigismund Bacstrom's Northwest Coast Drawings and an Account of his Curious Career DOUGLAS COLE Among the valuable collections of British pictures assembled by Mr. Paul Mellon is a remarkable series of "accurate and characteristic original Drawings and sketches" which visually chronicle "a late Voyage round the World in 1791, 92, 93, 94 and 95" by one "S. Bacstrom M.D. and Surgeon." Of the five dozen or so drawings and maps, twenty-nine relate to the northwest coast of America. Six pencil sketches of northwest coast subjects, in large part preliminary versions of the Mellon pictures, are in the Provincial Archives of British Columbia, while a finished watercolour of Nootka Sound is held by Parks Canada.1 Sigismund Bacstrom was not a professional artist. He probably had some training but most likely that which compliments a surgeon and scientist rather than an artist, His drawings are meticulous and precise, with great attention to detail and individuality. He was not concerned with the representative scene or the typical specimen. In his native portraits he does not tend to draw, as Cook's John Webber had done, "A Man of Nootka Sound" who would characterize all Nootka men; Bacstrom drew Hatzia, a Queen Charlotte Islands chief, and his wife and son as they sat before him on board the Three Brothers in Port Rose on Friday, 1 March 1793. The strong features of the three natives are neither flattered nor romanticized, and while the picture may not be "beautiful," it possesses a documentary value far surpassing the majority of eighteenth-century drawings of these New World natives. -

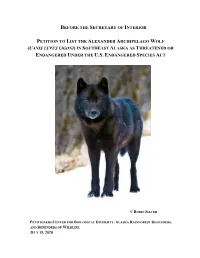

Petition to List the Alexander Archipelago Wolf in Southeast

BEFORE THE SECRETARY OF INTERIOR PETITION TO LIST THE ALEXANDER ARCHIPELAGO WOLF (CANIS LUPUS LIGONI) IN SOUTHEAST ALASKA AS THREATENED OR ENDANGERED UNDER THE U.S. ENDANGERED SPECIES ACT © ROBIN SILVER PETITIONERS CENTER FOR BIOLOGICAL DIVERSITY, ALASKA RAINFOREST DEFENDERS, AND DEFENDERS OF WILDLIFE JULY 15, 2020 NOTICE OF PETITION David Bernhardt, Secretary U.S. Department of the Interior 1849 C Street NW Washington, D.C. 20240 [email protected] Margaret Everson, Principal Deputy Director U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service 1849 C Street NW Washington, D.C. 20240 [email protected] Gary Frazer, Assistant Director for Endangered Species U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service 1840 C Street NW Washington, D.C. 20240 [email protected] Greg Siekaniec, Alaska Regional Director U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service 1011 East Tudor Road Anchorage, AK 99503 [email protected] PETITIONERS Shaye Wolf, Ph.D. Larry Edwards Center for Biological Diversity Alaska Rainforest Defenders 1212 Broadway P.O. Box 6064 Oakland, California 94612 Sitka, Alaska 99835 (415) 385-5746 (907) 772-4403 [email protected] [email protected] Randi Spivak Patrick Lavin, J.D. Public Lands Program Director Defenders of Wildlife Center for Biological Diversity 441 W. 5th Avenue, Suite 302 (310) 779-4894 Anchorage, AK 99501 [email protected] (907) 276-9410 [email protected] _________________________ Date this 15 day of July 2020 2 Pursuant to Section 4(b) of the Endangered Species Act (“ESA”), 16 U.S.C. §1533(b), Section 553(3) of the Administrative Procedures Act, 5 U.S.C. § 553(e), and 50 C.F.R. § 424.14(a), the Center for Biological Diversity, Alaska Rainforest Defenders, and Defenders of Wildlife petition the Secretary of the Interior, through the United States Fish and Wildlife Service (“USFWS”), to list the Alexander Archipelago wolf (Canis lupus ligoni) in Southeast Alaska as a threatened or endangered species. -

PRINCE of WALES ISLAND and VICINITY by Kenneth M

MINERAL INVESTIGATIONS IN THE KETCHIKAN MINING DISTRICT, ALASKA, 1991: PRINCE OF WALES ISLAND AND VICINITY By Kenneth M. Maas, Jan C. Still, and Peter E. Bittenbender U. S. DEPARTMENT of the INTERIOR Manuel Lujan, Jr., Secretary BUREAU of MINES T S Ary, Director OFR 81-92 CONTENTS Page Abstract s 1 Introduction 2 Location and Access .............................................. 2 Land Status . .................................................... 4 Acknowledgments ................................................. 4 Previous Studies: Northern Prince of Wales Island .......................... 6 Mining History: Northern Prince of Wales Island .......................... 7 Geologic Setting: Northern Prince of Wales Island .......................... 10 Bureau Investigations ............... ................................ 10 Northern Prince of Wales Island subarea ............................... 12 Craig subarea . .................................................. 12 Dall Island subarea ............................................... 13 Southeast Prince of Wales Island subarea ............................... 14 References . ...................................................... 15 Appendix A. - Analytical results ....................................... 19 Appendix B. - Sampling and analytical procedures ......................... 67 ILLUSTRATIONS 1. Ketchikan Mining District: 1991 study area showing Prince of Wales Island and vicinity. 3 2. Generalized land status map for Northern Prince of Wales Island 5 3. Generalized geologic map for Northern -

Dixon Entrance

118 ¢ U.S. Coast Pilot 8, Chapter 4 19 SEP 2021 Chart Coverage in Coast Pilot 8—Chapter 4 131°W 130°W NOAA’s Online Interactive Chart Catalog has complete chart coverage http://www.charts.noaa.gov/InteractiveCatalog/nrnc.shtml 133°W 132°W UNITEDCANADA ST ATES 17420 17424 56°N A 17422 C L L U A S R N R 17425 E I E N N E V C P I E L L A S D T N G R A I L B A G E E I L E T V A H N E D M A L 17423 C O C M I H C L E S P A B A L R N N I A A N L A N C C D E 17428 O F W 17430 D A 17427 Ketchikan N L A E GRAVINA ISLAND L S A T N I R S N E E O L G T R P A E T A S V S I E L N A L P I A S G S L D I L A G O N E D H D C O I N C 55°N H D A A N L N T E E L L DUKE ISLAND L N I I S L CORDOVA BAY D N A A N L T D R O P C Cape Chacon H A T H A 17437 17433 M S O Cape Muzon U N 17434 D DIXON ENTRANCE Langara Island 17420 54°N GRAHAM ISLAND HECATE STRAIT (Canada) 19 SEP 2021 U.S. -

Craig & Dixon Entrance Geophysics

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY An Interpretation of the Aeromagnetic and Gravity Data and Derivative Maps of the Craig and Dixon Entrance 1ox3o Quadrangles and the Western Edges of the Ketchikan and Prince Rupert Quadrangles, Southeastern Alaska By J.C. Wynn, R.P. Kucks, and D. J. Grybeck Digital Data Series 56 INTRODUCTION The U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) is required by the Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act (ANILCA, Public Law 96-487) to survey certain Federal lands to determine their mineral resource potential. As part of continuing studies designed to fulfill this responsibility, geochemical, geological and geophysical surveys of the Craig and Dixon Entrance (CDE) 1ox3o quadrangles in southeastern Alaska were undertaken by the USGS during the summers of 1983-85, 1989, and 1991. The geochemical data have been reported by Cathrall and others (1993) and Cathrall (1994). A simplified geologic map has been compiled especially for this report based largely on the work of Eberlein and others (1983) and Gehrels (1991, 1992). Brew (1996) also produced a compilation. This report presents available magnetic and gravity data and an interpretation thereof. GEOGRAPHIC AND GEOLOGIC SETTING OF THE CRAIG STUDY AREA The Craig study area comprises about 1,400 mi2 (3,600 km2) between latitude 54o40' and 56o N. and longitude 131o50' and 134o40' W. of the southeastern tip of the Alaskan Panhandle. The CDE quadrangles (fig. 1) are located west of Ketchikan and include all but the northern tip of Prince of Wales Island as well as outlying islands to the west from Dall Island in the south to Coronation Island in the northwest. -

Adult Sockeye and Pink Salmon Tagging Experiments for Separating Stocks in Northern British Columbia and Southern Southeast Alaska, 1982-1985

NOAA Technical Memorandum NMFS-AFSC-18 Adult Sockeye and Pink Salmon Tagging Experiments for Separating Stocks in Northern British Columbia and Southern Southeast Alaska, 1982-1985 by Jerome Pella, Margaret Hoffman, Stephen Hoffman, Michele Masuda, Sam Nelson, and Larry Talley U.S. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration National Marine Fisheries Service Alaska Fisheries Science Center August 1993 NOAA Technical Memorandum NMFS The National Marine Fisheries Service's Alaska Fisheries Science Center uses the NOAA Technical Memorandum series to issue informal scientific and technical publications when complete formal review and editorial processing are not appropriate or feasible. Documents within this series reflect sound professional work and may be referenced in the formal scientific and technical literature. The NMFS-AFSC Technical Memorandum series of the Alaska Fisheries Science Center continues the NMFS-F/NWC series established in 1970 by the Northwest Fisheries Center. The NMFS-NWFSC series will be used by the Northwest Fisheries Science Center. This document should be cited as follows: Pella, J., M. Hoffman, S. Hoffman, M. Masuda, S. Nelson, and L. Talley 1993. Adult sockeye and pink salmon tagging experiments for separating stocks in northern British Columbia and southern Southeast Alaska, 1982-1985 U.S. Dep. Commer., NOAA Tech. Memo. NMFS- AFSC-18, 134 p. Reference in this document to trade names does not imply endorsement by the National Marine Fisheries Service, NOAA. NOAA Technical Memorandum NMFS-AFSC-18 Adult Sockeye and Pink Salmon Tagging Experiments for Separating Stocks in Northern British Columbia and Southern Southeast Alaska, 1982-1985 bY Jerome Pella’, Margaret Hoffman’, Stephen Hoffman: Michele Masuda’, Sam Nelson’, and Larry Talley’ ‘Auke Bay Laboratory Alaska Fisheries Science Center 11305 Glacier Highway Juneau AK 99801-8626 ‘Alaska Department of Fish and Game Region 1 P.O. -

Background Information Regarding the Movements of Salmon Between Northern British Columbia and Southeast Alaska

BACKGROUND INFORMATION REGARDING THE MOVEMENTS OF SALMON BETWEEN NORTHERN BRITISH COLUMBIA AND SOUTHEAST ALASKA Prepared by Fisheries Research Board of Canada Biological Station Nanairno, B. c. October, 1965 ,·_: CONFIDENTIAL BACKGROUND INFORMATION REGARDING THE MOVEMENTS OF SALMON BETWEEN NORTHERN BRITISH COLUMBIA AND SOUTHEAST ALASKA Prepared by Fisheries Research Board of Canada Biological Station, Nanaimo, B. c. FOREWORD Joint consideration by the United States and Canada of management problems caused by the movements of salmon between Northern British Columbia and Southeast Alaska began with the formation in 1959 of an international 11 Committee on problems of mutual concern related to the conservation and 11 management of salmon stocks in Southeast Alaska and Northern British Columbia • Background information on events leading up to the formation of this Committee and a brief outline of the Committee's activities from 1959 to the present are included in Appendix A of this report. Details of the Committee's findings are included in the Committee's most recent report (April 196~), copies of which have already been distributed. Since studies reported by the Committee were completed, a considerable amount of tagging has been done by Canadian and United States vessels, both on the high seas and coastal waters, as part of the INPFC research program. A brief account of the results of these tagging programs bearing on the problem of movements of salmon in the Northern British Columbia~Southeast Alaska area is given in Appendix B. In the Committee's report, information on the extent of interception was not available for all areas of concern. For this reason some of the estimates were characterized as being ''minimum". -

Subsistence Harvests and Trade of Pacific Herring Spawn on Macrocystis Kelp in Hydaburg, Alaska

Technical Paper No. 225 Subsistence Harvests and Trade of Pacific Herring Spawn on Macrocystis Kelp in Hydaburg, Alaska by Anne-Marie Victor-Howe February 2008 Alaska Department of Fish and Game Division of Subsistence Symbols and Abbreviations The following symbols and abbreviations, and others approved for the Système International d'Unités (SI), are used without definition in the following reports by the Division of Subsistence. All others, including deviations from definitions listed below, are noted in the text at first mention, as well as in the titles or footnotes of tables, and in figure or figure captions. Weights and measures (metric) General Measures (fisheries) centimeter cm Alaska Administrative fork length FL deciliter dL Code AAC mideye-to-fork MEF gram g all commonly accepted mideye-to-tail-fork METF hectare ha abbreviations e.g., Mr., standard length SL kilogram kg Mrs., AM, PM, etc. total length TL kilometer km all commonly accepted liter L professional titles e.g., Dr., Mathematics, statistics meter m Ph.D., all standard mathematical milliliter mL R.N., etc. signs, symbols and millimeter mm at @ abbreviations compass directions: alternate hypothesis HA Weights and measures (English) east E base of natural logarithm e cubic feet per second ft3/s north N catch per unit effort CPUE foot ft south S coefficient of variation CV gallon gal west W common test statistics (F, t, χ2, inch in copyright © etc.) mile mi corporate suffixes: confidence interval CI nautical mile nmi Company Co. correlation coefficient ounce oz Corporation Corp. (multiple) R pound lb Incorporated Inc. correlation coefficient quart qt Limited Ltd. -

Information to Users

Spanish Exploration In The North Pacific And Its Effect On Alaska Place Names Item Type Thesis Authors Luna, Albert Gregory Download date 05/10/2021 11:44:10 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/11122/8541 INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6* x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. Bell & Howell Information and Learning 300 North Zeeb Road. Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA 800-521-0600 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner.