Borderlessness: Teamlab, Immersive Experience, and New Media Installation Art

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Preserving New Media Art: Re-Presenting Experience

Preserving New Media Art: Re-presenting Experience Jean Bridge Sarah Pruyn Visual Arts & Interactive Arts and Science, Theatre Studies, University of Guelph, Brock University Guelph, Canada St. Catharines, Canada [email protected] [email protected] ABSTRACT Keywords There has been considerable effort over the past 10 years to define methods for preservation, documentation and archive of new Art, performance art, relational art, interactive art, new media, art media artworks that are characterized variously as ephemeral, preservation, archive, art documentation, videogame, simulation, performative, immersive, participatory, relational, unstable or representation, experience, interaction, aliveness, virtual, technically obsolete. Much new media cultural heritage, authorship, instrumentality consisting of diverse and hybrid art forms such as installation, performance, intervention, activities and events, are accessible to 1. INTRODUCTION us as information, visual records and other relatively static This investigation has evolved from our interest in finding documents designed to meet the needs of collecting institutions documentation of artwork by artists who produce technologically and archives rather than those of artists, students and researchers mediated installations, performances, interventions, activities and who want a more affectively vital way of experiencing the artist’s events - the nature of which may be variously limited in time or creative intentions. It is therefore imperative to evolve existing duration, performance based, -

Sabbatical Leave Report 2019 – 2020

Sabbatical Leave Report 2019 – 2020 James MacDevitt, M.A. Associate Professor of Art History and Visual & Cultural Studies Director, Cerritos College Art Gallery Department of Art and Design Fine Arts and Communications Division Cerritos College January 2021 Table of Contents Title Page i Table of Contents ii Sabbatical Leave Application iii Statement of Purpose 35 Objectives and Outcomes 36 OER Textbook: Disciplinary Entanglements 36 Getty PST Art x Science x LA Research Grant Application 37 Conference Presentation: Just Futures 38 Academic Publication: Algorithmic Culture 38 Service and Practical Application 39 Concluding Statement 40 Appendix List (A-E) 41 A. Disciplinary Entanglements | Table of Contents 42 B. Disciplinary Entanglements | Screenshots 70 C. Getty PST Art x Science x LA | Research Grant Application 78 D. Algorithmic Culture | Book and Chapter Details 101 E. Just Futures | Conference and Presentation Details 103 2 SABBATICAL LEAVE APPLICATION TO: Dr. Rick Miranda, Jr., Vice President of Academic Affairs FROM: James MacDevitt, Associate Professor of Visual & Cultural Studies DATE: October 30, 2018 SUBJECT: Request for Sabbatical Leave for the 2019-20 School Year I. REQUEST FOR SABBATICAL LEAVE. I am requesting a 100% sabbatical leave for the 2019-2020 academic year. Employed as a fulltime faculty member at Cerritos College since August 2005, I have never requested sabbatical leave during the past thirteen years of service. II. PURPOSE OF LEAVE Scientific advancements and technological capabilities, most notably within the last few decades, have evolved at ever-accelerating rates. Artists, like everyone else, now live in a contemporary world completely restructured by recent phenomena such as satellite imagery, augmented reality, digital surveillance, mass extinctions, artificial intelligence, prosthetic limbs, climate change, big data, genetic modification, drone warfare, biometrics, computer viruses, and social media (and that’s by no means meant to be an all-inclusive list). -

Chapter 12. the Avant-Garde in the Late 20Th Century 1

Chapter 12. The Avant-Garde in the Late 20th Century 1 The Avant-Garde in the Late 20th Century: Modernism becomes Postmodernism A college student walks across campus in 1960. She has just left her room in the sorority house and is on her way to the art building. She is dressed for class, in carefully coordinated clothes that were all purchased from the same company: a crisp white shirt embroidered with her initials, a cardigan sweater in Kelly green wool, and a pleated skirt, also Kelly green, that reaches right to her knees. On her feet, she wears brown loafers and white socks. She carries a neatly packed bag, filled with freshly washed clothes: pants and a big work shirt for her painting class this morning; and shorts, a T-shirt and tennis shoes for her gym class later in the day. She’s walking rather rapidly, because she’s dying for a cigarette and knows that proper sorority girls don’t ever smoke unless they have a roof over their heads. She can’t wait to get into her painting class and light up. Following all the rules of the sorority is sometimes a drag, but it’s a lot better than living in the dormitory, where girls have ten o’clock curfews on weekdays and have to be in by midnight on weekends. (Of course, the guys don’t have curfews, but that’s just the way it is.) Anyway, it’s well known that most of the girls in her sorority marry well, and she can’t imagine anything she’d rather do after college. -

Digital Suprematism Overview

DIGITAL SUPREMATISM "Tom R. Chambers is a Texan with a “Russian, Suprematist soul”. He has repeatedly introduced the modern trend of new media art to the masses. He has brought Minimalism to the pixel. In 2000, Chambers began to look at the pixel in the context of Abstraction and Minimalism. And he is currently working with interpretations of Kazimir Malevich’s “Black Square” and other Suprematist forms. His work calls our attention to visual singularity, which is all that we see in the digital universe. Since the pixel corresponds to what we call “subatomic particles” in our physical universe, Chambers’ work connects us directly with the feeling of Russian Suprematism, described as the spirit that pervades everything, and pays tribute to the faith in the ability of abstraction to convey “net feeling in the work.” (Curator, OMG [One Month Gallery], Moscow, Russia, 2015) Chambers states: “I have always liked Minimalist works and as a digital artist, I began to explore the pixel as an art form in 2000. As I did research, and experimented with this picture element, I also began to read about Kazimir Malevich and his extreme Minimalist approach with ‘Black Square’. The more I contemplated his ‘Black Square’, the deeper I moved into the pixel and consequently the creation of the ‘My Dear Malevich’ project, which revealed similar to identical Suprematist forms that he created. I have focused on the pixel and his ‘Black Square’ ever since.” My Dear Malevich (MDM) (http://tomrchambers.com/malevich.html) In 2007, Chambers traveled (via magnification) into a digitized photograph of Malevich and discovered at the singular pixel level arrangements which echo back directly to Malevich's own totally abstract compositions. -

History of Modern Art Painting Sculpture Architecture Photography

HISTORY OF MODERN ART PAINTING SCULPTURE ARCHITECTURE PHOTOGRAPHY SEVENTH EDITION LK024_P0001EDarmason_HoMA_FM_Combined.indd i 14/09/2012 15:49 LK024_P0001EDarmason_HoMA_FM_Combined.indd ii 14/09/2012 15:49 HISTORY OF MODERN ART PAINTING SCULPTURE ARCHITECTURE PHOTOGRAPHY SEVENTH EDITION H.H. ARNASON ELIZABETH C. MANSFIELD National Humanities Center Boston Columbus Indianapolis New York San Francisco Upper Saddle River Amsterdam Cape Town Dubai London Madrid Milan Munich Paris Montréal Toronto Delhi Mexico City São Paulo Sydney Hong Kong Seoul Singapore Taipei Tokyo LK024_P0001EDarmason_HoMA_FM_Combined.indd iii 14/09/2012 15:49 Editorial Director: Craig Campanella This book was designed and produced by Editor-in-Chief: Sarah Touborg Laurence King Publishing Ltd, London Senior Sponsoring Editor: Helen Ronan www.laurenceking.com Editorial Assistant: Victoria Engros Production Manager: Simon Walsh Vice President, Director of Marketing: Brandy Dawson Page Design: Robin Farrow Executive Marketing Manager: Kate Mitchell Photo Researcher: Emma Brown Editorial Project Manager: David Nitti Copy Editor: Lis Ingles Production Liaison: Barbara Cappuccio Managing Editor: Melissa Feimer Senior Operations Supervisor: Mary Fischer Operations Specialist: Diane Peirano Senior Digital Media Editor: David Alick Media Project Manager: Rich Barnes Cover photo: Marcel Duchamp, Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2, 1912 (detail). Oil on canvas, 58 ϫ 35” (147.3 ϫ 88.9 cm). Philadelphia Museum of Art. page 2: Georges Seurat, A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte, 1884–86 (detail). 1 1 Oil on canvas, 6’ 9 ∕2” ϫ 10’ 1 ∕4” (2.1 ϫ 3.1 m). The Art Institute of Chicago. Credits and acknowledgments borrowed from other sources and reproduced, with permission, in this textbook appear on the appropriate page within text or in the picture credits on pages 809–16. -

A Strong Couple New Media and Socially Engaged

GENERAL ARTICLE A Strong Couple New Media and Socially Engaged Art SJOUKJE VA N DER MEULEN Despite the relevance of new media art for the critical understanding of temporary art world. The first is linked to the antagonism the information and network societies today, it is largely ignored as a between the art world and the new media art scene, as critics socially engaged practice—certainly compared to other forms of socially on both sides of this split have recognized. Media theorist engaged artistic practices in the international field of contemporary art. ABSTRACT This article outlines the reasons for this relative neglect and specifies Geert Lovink asks, for example: “Why is it so hard for artists different kinds of new media art that qualify for the category of socially that experiment with the latest technologies to be part of engaged art beyond leftist politics and ideologies transposed to the pop culture or ‘contemporary arts’?” [3]. Bishop also refers to realm of art. Proposing and mobilizing a “media-reflexive” art theory, this split: “There is, of course, an entire sphere of new media which emerged from the author’s doctoral dissertation, this claim is art, but this is a specialized field of its own: it rarely overlaps substantiated by the analysis of three exemplary digital art projects by with the mainstream art world” [4]. What art critics from Joseph Nechvatal, George Legrady and Blast Theory, respectively. Bishop to Bourriaud do not acknowledge, however, is that they contribute in no small measure to this “divide,” espe- Socially engaged art is a recurring topic in contemporary art, cially regarding socially engaged art. -

Installation Art 1 Installation Art

Installation art 1 Installation art Installation art describes an artistic genre of site-specific, three-dimensional works designed to transform a viewer's perception of a space. Generally, the term is applied to interior spaces, whereas exterior interventions are often called Land art; however the boundaries between these terms overlap. History Installation art can be either temporary or permanent. Installation artworks have been constructed in exhibition spaces such as museums and galleries, as well as public- and private spaces. The genre incorporates a very broad range of everyday and natural materials, which are often chosen for their evocative qualities, as well as new media such as video, sound, performance, immersive virtual reality and the internet. Many installations are site-specific in that they are designed to exist only in the space for which they were created. A number of institutions focusing on Installation art were created from the 1980s onwards, suggesting the need for Installation to be seen as a separate discipline. These included the Mattress Factory, Pittsburgh, the Museum of Installation in London, and the Fairy Doors of Ann Arbor, MI, among others. Installation art came to prominence in the 1970s but its roots can be identified in Marcel Duchamp, Fountain, 1917. earlier artists such as Marcel Duchamp and his use of the readymade and Kurt Photograph by Alfred Stieglitz Schwitters' Merz art objects, rather than more traditional craft based sculpture. The intention of the artist is paramount in much later installation art whose roots lie in the conceptual art of the 1960s. This again is a departure from traditional sculpture which places its focus on form. -

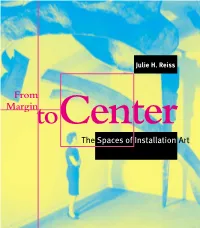

From Margin to Center: the Spaces of Installation

“Reiss offers a lucid argument for rethinking ‘Installation art’ and its challenge to the repressive and restrictive terms of the modernist art object. Her revisionism is a refreshing departure from the essentially formalist canon that continues to dis- tort the meaning and implications of the radical aesthetics of the 1960s.” —Maurice Berger, Senior Fellow, The Vera List focus is installations created in New Center for Art & Politics, New School for Social Reiss York City—which has a particularly Research Julie H. Reiss rich history of Installation art— Julie H. Reiss beginning in the late 1950s. She takes Margin From “Reiss’s narration of the progress of Installation From us from Allan Kaprow’s 1950s envi- art from alternative to mainstream is clear, well ronments to examples from minimal- Margin researched, and cogently argued.This book fills a ism, performance art, and process art toCenter void in the field of contemporary art history.” to establish Installation art’s autono- —Tom Finkelpearl, Program Director, P.S. 1 From The Spaces of Installation Art my as well as its relationship to other Contemporary Art Center movements. to Center Margin Recent years have seen a surge of Book and jacket design by Jean Wilcox. Unlike traditional art works, Installa- “From Margin to Center is a much-needed first his- interest in the effects of exhibition Front cover: Installation view of the exhi- tion art has no autonomous existence. tory of the development of Installation art in space, curatorial practice, and institu- bition A Sculpture by Herbert Ferber to Create It is usually created for a particular America. -

Installation Art and Experience

INTRODU INSTALLATION ART AND EXPERIENCE What is installation art? 'Installation art' is a term that loosely refers to the type of art into which the viewer physically enters, and which is often described as 'theatrical', 'immersive' or 'experiential'. However, the sheer diversity in terms of appearance, content and scope of the work produced today under this name, and the freedom with which the term is used, almost preclude it from having any meaning. The word 'installation' has now expanded to describe any arrangement of objects in any given space, to the point where it can happily be applied even to a conventional display of paintings on a wall. But there is a fine line between an installation of art and installation art. This ambiguity has been present since the terms first came into use in the r 960s. During this decade, the word 'installation' was employed by art magazines to describe the way in which an exhibition was arranged. The photographic documentation of this arrangement was termed an 'installation shot', and this gave rise to the use of the word for works that used the whole space as 'installation art'. Since then, the distinction between an installation of works of art and 'installation art' proper has become increasingly blurred. What both terms have in common is a desire to heighten the viewer's awareness of how objects are positioned (installed) in a space, and of our bodily response to this. However, there are also important differences. An installation of art is secondary in importance to the individual works it contains, while in a work of installation art, the space, and the ensemble of elements within it, are regarded in their entirety as a singular entity. -

New Media Art and Institutional Critique: Networks Vs

New Media Art and Institutional Critique: Networks vs. Institutions Christiane Paul New media art has inspired a variety of dreams about our technological future, among them the dream of a more or less radical reconfiguration of museums and art institutions. As a process-oriented art form that is inherently collaborative, participatory, networked and variable, new media practice tends to challenge the structures and logic of museums and art galleries and reorients the concept and arena of the exhibition. New media art seems to call for a "ubiquitous museum" or "museum without walls," a parallel, distributed, living information space open to artistic interference—a space for exchange, collaborative creation, and presentation that is transparent and flexible. This notion of an "open museum" reaches further than the concept of a postmodern museum without walls outlined by Rosalind Krauss, (1) according to which architectural structures create a visually and physically decentring movement by opening relational spaces in a referential process that continuously questions formal order. By virtue of its highly contextual and often networked nature, new media art both extends beyond the walls and structures of the museum and, at times, undermines the museum's very logic of exhibition and collection. The fact that new media art has its roots in the military-industrial-academic complex and is closely linked to "entertainment systems" adds further contexts. While all art forms and the movements that sustain them are embedded in a larger cultural context, new media can never be understood from a strictly art historical perspective: the history of technology and media sciences plays an equally important role in the formation and reception of new media art practices. -

Installation Art and Experience

TRODUCTION INSTALLATION ART AND EXPERIENCE What is installation art? 'Installation art' is a term that loosely refers to the type of art into which the viewer physically enters, and which is often described as 'theatrical', 'immersive' or 'experiential'. However, the sheer diversity in terms of appearance, content and scope of the work produced today under this name, and the freedom with which the term is used, almost preclude it from having any meaning. The word 'installation' has now expanded to describe any arrangement of objects in any given space, to the point where it can happily be applied even to a conventional display of paintings on a wall. But there is a fine line between an installation of art and installation art. This ambiguity has been present since the terms first came into use in the 1960s. During this decade, the word 'installation' was employed by art magazines to describe the way in which an exhibition was arranged. The photographic documentation of this arrangement was termed an 'installation shot', and this gave rise to the use of the word for works that used the whole space as 'installation art'. Since then, the distinction between an installation of works of art and 'installation art' proper has become increasingly blurred. What both terms have in common is a desire to heighten the viewer's awareness of how objects are positioned (installed) in a space, and of our bodily response to this. However, there are also important differences. An installation of art is secondary in importance to the individual works it contains, while in a work of installation art, the space, and the ensemble of elements within it, are regarded in their entirety as a singular entity. -

Installation Art in India: Concepts and Roots

[Aaftab *, Vol.4 (Iss.10): October, 2016] ISSN- 2350-0530(O) ISSN- 2394-3629(P) IF: 4.321 (CosmosImpactFactor), 2.532 (I2OR) Arts INSTALLATION ART IN INDIA: CONCEPTS AND ROOTS Mohsina Aaftab *1 *1 Research Scholar, Department of Fine Arts, A.M.U., Aligarh, INDIA DOI: https://doi.org/10.29121/granthaalayah.v4.i10.2016.2483 ABSTRACT Present study focuses on the new media Installation Art in India, its present scenario, and backgrounds. Essentially installation art has taken its heritage from conceptual art, which came into prominence in 1970s, when the concept or idea was prominent – when an artist uses a conceptual form of art which means that all of the arrangement and conclusion are made previously and the implementation is an obligatory concern. So, spontaneously idea became a machine that makes the art. An idea suddenly pops in his mind and he just implemented it, in his very own way. This kind of art does not narrow itself to gallery spaces and can refer to any materials intervention in everyday public or private spaces. After India became independent, art began to change here. considerately several movements and group bounced up all over the country headed by ambitious young artists with vision of bringing modern art to India. Now the art of India is totally changed. Contemporaries are not bound to use paper and canvas, wall or any other art surfaces. They are not bound to make mythological paintings or sculptures but they are free to do anything, they are free to use any medium, material and space they want.