Threat Tactics Report: North Korea

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ISSUE 5 AADH05 OFC+Spine.Indd 1 the Mortar Company

ARTILLERY AND AIR DEFENCE ARTILLERY ISSUE 5 HANDBOOK HANDBOOK – ISSUE 5 PUBLISHED MARCH 2018 THE CONCISE GLOBAL INDUSTRY GUIDE ARTILLERY AND AIR DEFENCE AADH05_OFC+spine.indd 1 3/16/2018 10:18:59 AM The Mortar Company. CONFRAG® CONTROLS – THE NEW HIGH EXPLOSIVE STANDARD HDS has developed CONFRAG® technology to increase the lethal performance of the stan- dard High Explosive granade for 60 mm CDO, 60 mm, 81 mm and 120 mm dramatically. The HE lethality is increased by controlling fragmentation mass and quantity, fragment velocity and fragment distribution, all controlled by CONFRAG® technology. hds.hirtenberger.com AADH05_IFC_Hirtenberger.indd 2 3/16/2018 9:58:03 AM CONTENTS Editor 3 Introduction Tony Skinner. [email protected] Grant Turnbull, Editor of Land Warfare International magazine, welcomes readers to Reference Editors Issue 5 of Shephard Media’s Artillery and Air Defence Handbook. Ben Brook. [email protected] 4 Self-propelled howitzers Karima Thibou. [email protected] A guide to self-propelled artillery systems that are under development, in production or being substantially modernised. Commercial Manager Peter Rawlins [email protected] 29 Towed howitzers Details of towed artillery systems that are under development, in production or Production and Circulation Manager David Hurst. being substantially modernised. [email protected] 42 Self-propelled mortars Production Elaine Effard, Georgina Kerridge Specifications for self-propelled mortar systems that are under development, in Georgina Smith, Adam Wakeling. production or being substantially modernised. Chairman Nick Prest 53 Towed mortars Descriptions of towed heavy mortar systems that are under development, in CEO Darren Lake production or being substantially modernised. -

Trend Analysis the Israeli Unit 8200 an OSINT-Based Study CSS

CSS CYBER DEFENSE PROJECT Trend Analysis The Israeli Unit 8200 An OSINT-based study Zürich, December 2019 Risk and Resilience Team Center for Security Studies (CSS), ETH Zürich Trend analysis: The Israeli Unit 8200 – An OSINT-based study Author: Sean Cordey © 2019 Center for Security Studies (CSS), ETH Zurich Contact: Center for Security Studies Haldeneggsteig 4 ETH Zurich CH-8092 Zurich Switzerland Tel.: +41-44-632 40 25 [email protected] www.css.ethz.ch Analysis prepared by: Center for Security Studies (CSS), ETH Zurich ETH-CSS project management: Tim Prior, Head of the Risk and Resilience Research Group, Myriam Dunn Cavelty, Deputy Head for Research and Teaching; Andreas Wenger, Director of the CSS Disclaimer: The opinions presented in this study exclusively reflect the authors’ views. Please cite as: Cordey, S. (2019). Trend Analysis: The Israeli Unit 8200 – An OSINT-based study. Center for Security Studies (CSS), ETH Zürich. 1 Trend analysis: The Israeli Unit 8200 – An OSINT-based study . Table of Contents 1 Introduction 4 2 Historical Background 5 2.1 Pre-independence intelligence units 5 2.2 Post-independence unit: former capabilities, missions, mandate and techniques 5 2.3 The Yom Kippur War and its consequences 6 3 Operational Background 8 3.1 Unit mandate, activities and capabilities 8 3.2 Attributed and alleged operations 8 3.3 International efforts and cooperation 9 4 Organizational and Cultural Background 10 4.1 Organizational structure 10 Structure and sub-units 10 Infrastructure 11 4.2 Selection and training process 12 Attractiveness and motivation 12 Screening process 12 Selection process 13 Training process 13 Service, reserve and alumni 14 4.3 Internal culture 14 5 Discussion and Analysis 16 5.1 Strengths 16 5.2 Weaknesses 17 6 Conclusion and Recommendations 18 7 Glossary 20 8 Abbreviations 20 9 Bibliography 21 2 Trend analysis: The Israeli Unit 8200 – An OSINT-based study selection tests comprise a psychometric test, rigorous Executive Summary interviews, and an education/skills test. -

25 Interagency Map Pmedequipment.Mxd

Onsong Kyongwon North Kyonghung Hamgyong Hoiryong City Provision of Medical Equipment Musan Chongjin City Taehongdan Puryong Samjiyon Yonsa Junggang Ryanggang Kyongsong Pochon Paekam Jasong Orang Kimhyongjik Hyesan City Unhung Hwaphyong Kimjongsuk Myonggan Manpo City Samsu Kapsan Janggang Kilju Myongchon Sijung Chagang Kanggye City Rangrim Pungso Hwadae Chosan Wiwon Songgang Pujon Hochon Kimchaek City Kimhyonggwon North Usi Responsible Agency Kopung Jonchon South Hamgyong Phyongan Pyokdong Ryongrim Tanchon City Changsong Jangjin Toksong Sakju Songwon Riwon WHO Sinhung Uiju Tongsin Taegwan Tongchang Pukchong Huichon City Sinuiju City Hongwon Sinpho City UNFPA Chonma Unsan Yonggwang Phihyon Taehung Ryongchon Hyangsan Kusong City Hamhung City Sindo Nyongwon UNICEF Yomju Tongrim Thaechon Kujang Hamju Sonchon Rakwon Cholsan Nyongbyon IFRC Pakchon Tokchon City Kwaksan Jongju City Unjon Jongphyong Kaechon City Yodok Maengsan EUPS 1 Anju City Pukchang Mundok Kumya Sunchon City Kowon EUPS 3 Sukchon SouthSinyang Sudong Pyongsong City Chonnae Pyongwon Songchon EUPS 7 PhyonganYangdok Munchon City Jungsan Wonsan City Taedong Pyongyang City Kangdong Hoichang Anbyon Free Trade Zone Kangso Sinpyong Popdong PyongyangKangnam North Thongchon Onchon Junghwa Yonsan Kosan Taean Sangwon No Access Allowed Nampo City Hwanghae Hwangju Koksan Hoiyang Suan Pangyo Sepho Unchon Yontan Kumgang Kosong Unryul Sariwon City South Singye Kangwon Changdo Anak Pongsan Sohung Ichon Phyonggang Kwail Kimhwa Hwanghae Jaeryong Songhwa Samchon Unpha Phyongsan Sinchon Cholwon Jangyon Rinsan Tosan Ryongyon Sinwon Kumchon Taetan Pongchon Pyoksong Jangphung Haeju City Kaesong City Chongdan Ongjin Paechon Yonan Kaepung Map compliled by VAM Unit Kangryong WFP DPRK Feb 2010. -

Hezbollah's Missiles and Rockets

JULY 2017 CSIS BRIEFS CSIS Hezbollah’s Missiles and Rockets An Overview By Shaan Shaikh and Ian Williams JULY 2018 THE ISSUE Hezbollah is the world’s most heavily armed non-state actor, with a large and diverse stockpile of unguided artillery rockets, as well as ballistic, antiair, antitank, and antiship missiles. Hezbollah views its rocket and missile arsenal as its primary deterrent against Israeli military action, while also useful for quick retaliatory strikes and longer military engagements. Hezbollah’s unguided rocket arsenal has increased significantly since the 2006 Lebanon War, and the party’s increased role in the Syrian conflict raises concerns about its acquisition of more sophisticated standoff and precision-guided missiles, whether from Syria, Iran, or Russia. This brief provides a summary of the acquisition history, capabilities, and use of these forces. CENTER FOR STRATEGIC & middle east INTERNATIONAL STUDIES program CSIS BRIEFS | WWW.CSIS.ORG | 1 ezbollah is a Lebanese political party public source information and does not cover certain topics and militant group with close ties to such as rocket strategies, evolution, or storage locations. Iran and Syria’s Assad regime. It is the This brief instead focuses on the acquisition history, world’s most heavily armed non-state capabilities, and use of these forces. actor—aptly described as “a militia trained like an army and equipped LAND ATTACK MISSILES AND ROCKETS like a state.”1 This is especially true Hwith regard to its missile and rocket forces, which Hezbollah 107 AND 122 MM KATYUSHA ROCKETS has arrayed against Israel in vast quantities. The party’s arsenal is comprised primarily of small, man- portable, unguided artillery rockets. -

North Korea's Political System*

This article was translated by JIIA from Japanese into English as part of a research project to promote academic studies on the international circumstances in the Asia-Pacific. JIIA takes full responsibility for the translation of this article. To obtain permission to use this article beyond the scope of your personal use and research, please contact JIIA by e-mail ([email protected]) Citation: International Circumstances in the Asia-Pacific Series, Japan Digital Library (March 2016), http://www2.jiia.or.jp/en/digital_library/korean_peninsula.php Series: Korean Peninsula Affairs North Korea’s Political System* Takashi Sakai** Introduction A year has passed since the birth of the Kim Jong-un regime in North Korea following the sudden death of General Secretary Kim Jong-il in December 2011. During the early days of the regime, many observers commented that all would not be smooth sailing for the new regime, citing the lack of power and previ- ous experience of the youthful Kim Jong-un as a primary cause of concern. However, on the surface at least, it now appears that Kim Jong-un is now in full control of his powers as the “Guiding Leader” and that the political situation is calm. The crucial issue is whether the present situation is stable and sustain- able. To consider this issue properly, it is important to understand the following series of questions. What is the current political structure in North Korea? Is the political structure the same as that which existed under the Kim Jong-il regime, or have significant changes occurred? What political dynamics are at play within this structure? Answering these questions with any degree of accuracy is not an easy task. -

IDF Special Forces – Reservists – Conscientious Objectors – Peace Activists – State Protection

Refugee Review Tribunal AUSTRALIA RRT RESEARCH RESPONSE Research Response Number: ISR35545 Country: Israel Date: 23 October 2009 Keywords: Israel – Netanya – Suicide bombings – IDF special forces – Reservists – Conscientious objectors – Peace activists – State protection This response was prepared by the Research & Information Services Section of the Refugee Review Tribunal (RRT) after researching publicly accessible information currently available to the RRT within time constraints. This response is not, and does not purport to be, conclusive as to the merit of any particular claim to refugee status or asylum. This research response may not, under any circumstance, be cited in a decision or any other document. Anyone wishing to use this information may only cite the primary source material contained herein. Questions 1. Please provide information on suicide bombs in 2000 to January 2002 in Netanya. 2. Deleted. 3. Please provide any information on recruitment of individuals to special army units for “chasing terrorists in neighbouring countries”, how often they would be called up, and repercussions for wanting to withdraw? 4. What evidence is there of repercussions from Israeli Jewish fanatics and Arabs or the military towards someone showing some pro-Palestinian sentiment (attending rallies, expressing sentiment, and helping Arabs get jobs)? Is there evidence there would be no state protection in the event of being harmed because of political opinions held? RESPONSE 1. Please provide information on suicide bombs in 2000 to January 2002 in Netanya. According to a 2006 journal article published in GeoJournal there were no suicide attacks in Netanya during the period of 1994-2000. No reports of suicide bombings in 2000 in Netanya were found in a search of other available sources. -

The Vietnam War 47

The Vietnam War 47 Chapter Three The Vietnam War POSTWAR DEMOBILIZATION By the end of 1945, the Army and Navy had demobilized about half their strength, and most of the rest was demobilized in 1946. Millions of men went home, got jobs, took advantage of the new Servicemen’s Readjustment Act (commonly known as the “GI Bill,” passed in 1944), got married, and started the “baby boom.” Just as in the period following victory in World War I, few Americans paid much attention to national defense. The newly created Department of Defense (formed in the 1947 merger of the War Department and the Navy Department) faced several concurrent tasks: demobilizing the troops; selling off surplus equipment, land, and buildings; and calculating what defense forces the United States actually needed. The govern- ment adopted a postwar defense policy of containing communism, centered on supporting the governments of foreign countries struggling against internal communists. In its early stages, containment called for foreign aid (both military and economic) and limited numbers of military advisers. The Army drew down to only a few divisions, mostly serving occupation duty in Germany and Japan, and most at two-thirds strength. So few men were volunteering for the military that, in 1948, Congress restored a peacetime draft. The world began looking like a more dangerous place when the Soviets cut off land access to Berlin and backed a coup in Czechoslovakia that replaced a coalition government with a communist one. Such events, in addition to the campaign led by Senator Joe Mc- Carthy to expose any possible American communists, stoked fears of a world- wide communist movement. -

International Conference KNOWLEDGE-BASED ORGANIZATION Vol

International Conference KNOWLEDGE-BASED ORGANIZATION Vol. XXIII No 1 2017 RISK MANAGEMENT IN THE DECISION MAKING PROCESS CONCERNING THE USE OF OUTSOURCING SERVICES IN THE BULGARIAN ARMED FORCES Nikolay NICHEV “Vasil Levski“ National Military University, Veliko Tarnovo, Bulgaria [email protected] Abstract: Outsourcing services in the armed forces are a promising tool for reducing defence spending which use shall be determined by previously made accurate analysis of peacetime and wartime tasks of army structures. The decision to implement such services allows formations of Bulgarian Army to focus on the implementation of specific tasks related to their combat training. Outsourcing is a successful practice which is applied both in the armies of the member states of NATO and in the Bulgarian Army. Using specialized companies to provide certain services in formations provides a reduction in defence spending, access to technology and skills in terms of financial shortage. The aim of this paper is to analyse main outsourcing risks that affect the relationship between the military formation of the Bulgarian army, the structures of the Ministry of Defence of the Republic of Bulgaria and service providers, and to assess those risks. The basic steps for risk management in outsourcing activities are determined on this base. Keywords: outsourcing, risk management, outsourcing risk 1. Introduction It is measured by its impact and the Outsourcing is an effective tool to generate probability of occurrence, and its new revenue, and the risks that may arise, management is the process of identifying, draw our attention to identifying the main analysing, evaluating, monitoring, types of outsourcing risks. This requires the countering and reporting the risks that may focus of current research on studying and affect the achievement of the objectives of evaluating the possibility of the occurrence an organisation and the implementation of of such risks, and the development of a the necessary control activities in order to system for risks management on this basis. -

Digital Trenches

Martyn Williams H R N K Attack Mirae Wi-Fi Family Medicine Healthy Food Korean Basics Handbook Medicinal Recipes Picture Memory I Can Be My Travel Weather 2.0 Matching Competition Gifted Too Companion ! Agricultural Stone Magnolia Escpe from Mount Baekdu Weather Remover ERRORTelevision the Labyrinth Series 1.25 Foreign apps not permitted. Report to your nearest inminban leader. Business Number Practical App Store E-Bookstore Apps Tower Beauty Skills 2.0 Chosun Great Chosun Global News KCNA Battle of Cuisine Dictionary of Wisdom Terms DIGITAL TRENCHES North Korea’s Information Counter-Offensive DIGITAL TRENCHES North Korea’s Information Counter-Offensive Copyright © 2019 Committee for Human Rights in North Korea Printed in the United States of America All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including photocopying, recording, or other electronic or mechanical methods, without the prior permission of the Committee for Human Rights in North Korea, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical reviews and certain other noncommercial uses permitted by copyright law. Committee for Human Rights in North Korea 1001 Connecticut Avenue, NW, Suite 435 Washington, DC 20036 P: (202) 499-7970 www.hrnk.org Print ISBN: 978-0-9995358-7-5 Digital ISBN: 978-0-9995358-8-2 Library of Congress Control Number: 2019919723 Cover translations by Julie Kim, HRNK Research Intern. BOARD OF DIRECTORS Gordon Flake, Co-Chair Katrina Lantos Swett, Co-Chair John Despres, -

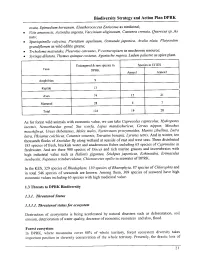

CBD Strategy and Action Plan

Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan DPRK ovata, Epimedium koreanum, Eleutherococcus Enticosus as medicinal; · Vitis amurensis, Actinidia argenta, Vaccinium uliginosum, Castanea crenata, Querecus sp._As nuts; · Spuriopinella calycina, Pteridium aquilinum, Osmunda japonica, Aralia elata, Platycodon grandifiorum as wild edible greens; · Trcholoma matsutake, 'Pleurotus ostreatus, P. cornucopiaen as mushroom resource; · Syringa dilatata, Thylgus quinque costatus, Agastache rugosa, Ledum palustre as spice plant. Endangered & rare species in Species inCITES Taxa DPRK Annexl Annex2 . Amphibian 9 Reptile 13 Aves 74 15 2 I Mammal 28 4 7 Total 124 19 28 As for forest wild animals with economic value, we can take Caprecolus caprecolus, Hydropotes inermis, Nemorhaedus goral, Sus scorfa, Lepus mandschuricus, Cervus nippon, Moschus moschiferus, Ursus thibetatnus, Meles meles, Nyctereutes procyonoides, Martes zibellina, Lutra lutra, Phsianus colchicus, Coturnix xoturnix, Tetrastes bonasia, Lyrurus tetrix. And in winter, ten thousands flocks of Anatidae fly along wetland at seaside of east and west seas. There distributed 185 species of fresh, brackish water and anadromous fishes including 65 species of Cyprinidae in freshwater. And are there 900 species of Disces and rich marine grasses and invertebrates with high industrial value such as Haliotis gigantea, Stichpus japonicus, Echinoidea, Erimaculus isenbeckii, Neptunus trituberculatus, Chionoecetes opilio in seawater of DPRK. In the KES, 329 species of Rhodophyta, 130 species of Rhaeophyta, 87 species of Chlorophta and in total 546 species of seaweeds are known. Among them, 309 species of seaweed have high economic values including 63 species with high medicinal value. 1.3 Threats to DPRK Biodiversity 1.3. L Threatened Status 1.3.1.1. Threatened status for ecosystem Destruction of ecosystems is being accelerated by natural disasters such as deforestation, soil erosion, deterioration of water quality, decrease of economic resources and also, flood. -

PK2018-07-OCR.Pdf

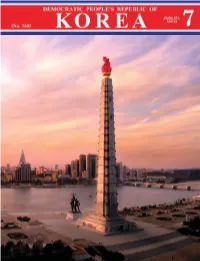

CONTENTS Δ Supreme Leader Kim Jong Un Inspecting Δ Emphasis on Effective Use of Natural Energy. ............18 Completed Koam-Tapchon Railway ................................1 Δ Sanatorium at the Foot of Mt Ryongak ........................20 Δ Supreme Leader’s Field Guidance at Construction Δ Moran Hill, People’s Cultural Recreation Area ............22 Site of Wonsan-Kalma Coastal Tourist Area....................4 Δ Amateur Riders .............................................................26 Δ Effervescent DPRK-China Friendship .............................6 Δ 2018 Spring Table Tennis Tournament of Δ Supreme Leader Kim Jong Un Meeting the Disabled and Amateurs Held ..................................26 Chinese Foreign Minister ...............................................10 Δ Little Janggu Players ....................................................28 Δ Supreme Leader Kim Jong Un Meeting Δ Sinuiju Traffi c Safety Education US State Secretary. .........................................................11 Park for Children ..........................................................30 Δ Historic Fourth North-South Summit .............................12 Δ To Preserve National Soul and Flavour ........................32 Δ Gold Prizes Awarded to Δ Like Real Brothers and Sisters .....................................34 Kimilsungia and Kimjongilia.........................................14 Δ Laugh Heartily and Grow Up Happily .........................36 Δ Day of the Sun Celebrated Grandly ...............................15 Δ First Olympic Medallist -

North Korea's Biological Weapons Program

Zhzh PROJECT ON MANAGING THE MICROBE North Korea’s Biological Weapons Program The Known and Unknown Hyun-Kyung Kim Elizabeth Philipp Hattie Chung REPORT OCTOBER 2017 Project on Managing the Microbe Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs Harvard Kennedy School 79 JFK Street Cambridge, MA 02138 www.belfercenter.org/Managing-Microbe Statements and views expressed in this report are solely those of the authors and do not imply endorsement by Harvard University, the Harvard Kennedy School, or the Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs. Design & Layout by Andrew Facini Cover photo: A satellite view of the Pyongyang Bio-Technical Institute, April 22, 2017. ©2016 Google Earth, CNES/Airbus. Used with Permission. Copyright 2017, President and Fellows of Harvard College Printed in the United States of America PROJECT ON MANAGING THE MICROBE The Known and Unknown North Korea’s Biological Weapons Program Hyun-Kyung Kim Elizabeth Philipp Hattie Chung REPORT OCTOBER 2017 Acknowledgments We are grateful to our colleagues and mentors in the Belfer Center Project on Managing the Microbe for their support for this paper, particularly the former project directors Hon. Andrew C. Weber and Dr. Barry Bloom, research associate Maria Ben Assa, and visiting distinguished scholar Dr. Vernon Gibson. We would like to thank the experts who graciously participated in interviews for this study, including Dr. Bruce Bennett, Mr. Joseph Bermudez, Dr. Jim Collins, Ms. Melissa Hanham, Mr. Milton Leitenberg, Mr. Joshua Pollack, Dr. Pam Silver, and Dr. Wendin Smith. We would also like to extend our gratitude towards the AMPLYFI team who provided us with new insights into research methodology.