(North) Korea Rajarshi Sen

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CBD Strategy and Action Plan

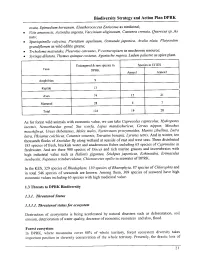

Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan DPRK ovata, Epimedium koreanum, Eleutherococcus Enticosus as medicinal; · Vitis amurensis, Actinidia argenta, Vaccinium uliginosum, Castanea crenata, Querecus sp._As nuts; · Spuriopinella calycina, Pteridium aquilinum, Osmunda japonica, Aralia elata, Platycodon grandifiorum as wild edible greens; · Trcholoma matsutake, 'Pleurotus ostreatus, P. cornucopiaen as mushroom resource; · Syringa dilatata, Thylgus quinque costatus, Agastache rugosa, Ledum palustre as spice plant. Endangered & rare species in Species inCITES Taxa DPRK Annexl Annex2 . Amphibian 9 Reptile 13 Aves 74 15 2 I Mammal 28 4 7 Total 124 19 28 As for forest wild animals with economic value, we can take Caprecolus caprecolus, Hydropotes inermis, Nemorhaedus goral, Sus scorfa, Lepus mandschuricus, Cervus nippon, Moschus moschiferus, Ursus thibetatnus, Meles meles, Nyctereutes procyonoides, Martes zibellina, Lutra lutra, Phsianus colchicus, Coturnix xoturnix, Tetrastes bonasia, Lyrurus tetrix. And in winter, ten thousands flocks of Anatidae fly along wetland at seaside of east and west seas. There distributed 185 species of fresh, brackish water and anadromous fishes including 65 species of Cyprinidae in freshwater. And are there 900 species of Disces and rich marine grasses and invertebrates with high industrial value such as Haliotis gigantea, Stichpus japonicus, Echinoidea, Erimaculus isenbeckii, Neptunus trituberculatus, Chionoecetes opilio in seawater of DPRK. In the KES, 329 species of Rhodophyta, 130 species of Rhaeophyta, 87 species of Chlorophta and in total 546 species of seaweeds are known. Among them, 309 species of seaweed have high economic values including 63 species with high medicinal value. 1.3 Threats to DPRK Biodiversity 1.3. L Threatened Status 1.3.1.1. Threatened status for ecosystem Destruction of ecosystems is being accelerated by natural disasters such as deforestation, soil erosion, deterioration of water quality, decrease of economic resources and also, flood. -

PK2018-07-OCR.Pdf

CONTENTS Δ Supreme Leader Kim Jong Un Inspecting Δ Emphasis on Effective Use of Natural Energy. ............18 Completed Koam-Tapchon Railway ................................1 Δ Sanatorium at the Foot of Mt Ryongak ........................20 Δ Supreme Leader’s Field Guidance at Construction Δ Moran Hill, People’s Cultural Recreation Area ............22 Site of Wonsan-Kalma Coastal Tourist Area....................4 Δ Amateur Riders .............................................................26 Δ Effervescent DPRK-China Friendship .............................6 Δ 2018 Spring Table Tennis Tournament of Δ Supreme Leader Kim Jong Un Meeting the Disabled and Amateurs Held ..................................26 Chinese Foreign Minister ...............................................10 Δ Little Janggu Players ....................................................28 Δ Supreme Leader Kim Jong Un Meeting Δ Sinuiju Traffi c Safety Education US State Secretary. .........................................................11 Park for Children ..........................................................30 Δ Historic Fourth North-South Summit .............................12 Δ To Preserve National Soul and Flavour ........................32 Δ Gold Prizes Awarded to Δ Like Real Brothers and Sisters .....................................34 Kimilsungia and Kimjongilia.........................................14 Δ Laugh Heartily and Grow Up Happily .........................36 Δ Day of the Sun Celebrated Grandly ...............................15 Δ First Olympic Medallist -

North Korea's Biological Weapons Program

Zhzh PROJECT ON MANAGING THE MICROBE North Korea’s Biological Weapons Program The Known and Unknown Hyun-Kyung Kim Elizabeth Philipp Hattie Chung REPORT OCTOBER 2017 Project on Managing the Microbe Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs Harvard Kennedy School 79 JFK Street Cambridge, MA 02138 www.belfercenter.org/Managing-Microbe Statements and views expressed in this report are solely those of the authors and do not imply endorsement by Harvard University, the Harvard Kennedy School, or the Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs. Design & Layout by Andrew Facini Cover photo: A satellite view of the Pyongyang Bio-Technical Institute, April 22, 2017. ©2016 Google Earth, CNES/Airbus. Used with Permission. Copyright 2017, President and Fellows of Harvard College Printed in the United States of America PROJECT ON MANAGING THE MICROBE The Known and Unknown North Korea’s Biological Weapons Program Hyun-Kyung Kim Elizabeth Philipp Hattie Chung REPORT OCTOBER 2017 Acknowledgments We are grateful to our colleagues and mentors in the Belfer Center Project on Managing the Microbe for their support for this paper, particularly the former project directors Hon. Andrew C. Weber and Dr. Barry Bloom, research associate Maria Ben Assa, and visiting distinguished scholar Dr. Vernon Gibson. We would like to thank the experts who graciously participated in interviews for this study, including Dr. Bruce Bennett, Mr. Joseph Bermudez, Dr. Jim Collins, Ms. Melissa Hanham, Mr. Milton Leitenberg, Mr. Joshua Pollack, Dr. Pam Silver, and Dr. Wendin Smith. We would also like to extend our gratitude towards the AMPLYFI team who provided us with new insights into research methodology. -

The Political Bureau of the Central Committee Of

Political Bureau of WPK Central Committee Met CONTENTS he Political Bureau of the Central Committee of Δ Political Bureau of WPK Central Tthe Workers’ Party of Korea met on April 11 at the Committee Met‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥ 1 headquarters building of the WPK Central Committee. Kim Jong Un, chairman of the Workers’ Party Δ Supreme Leader Kim Jong Un of Korea, chairman of the State Affairs Commission of the DPRK and supreme commander of the armed Inspects Army Units‥ ‥‥‥‥‥‥‥ 2 forces of the DPRK, attended the meeting. Δ Third Session of the 14th SPA Present there were also members and alternate members of the Political Bureau of the WPK Central of the DPRK Held‥ ‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥ 4 Committee. Upon authorization of the Political Bureau of the Δ Pyongyang Yesterday and Today‥‥‥ 6 Party Central Committee, Chairman Kim Jong Un Δ Kangwon Province Prospers presided over the meeting. The meeting decided its agenda items. by Dint of Self-reliance‥‥‥‥‥‥ 14 Discussing its first agenda item, the meeting Δ Spring of Namri Village emphasized the need to consistently take strict national countermeasures to cope with the steady spread of the in Mangyongdae‥ ‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥ 20 pandemic and thoroughly check the inroads of the virus. Δ Training into Masters of Sky‥‥‥‥ 22 It studied and discussed issues of adjusting and Δ Centenarian Woman‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥ 24 changing some policy tasks in the implementation of the decisions made at the Fifth Plenary Meeting of the Δ For the Football Development Seventh Central Committee of the WPK in view of the of the Country‥ ‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥ 25 prevailing internal and external climates. A joint resolution of the Central Committee of the Δ Blessed Triplets‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥ 26 WPK, the State Affairs Commission of the DPRK and the DPRK Cabinet “On more thoroughly taking state Δ Chollima General Building-Materials measures to protect our people’s lives and safety from Factory‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥‥ 28 the worldwide epidemic” was adopted at the meeting. -

Toward a (Sub)-Regionalization of South Korea's Unification Policy – the Proposal of a Romantic Road for Gangwon Province

https://doi.org/10.33728/ijkus.2020.29.1.008 International Journal of Korean Unification Studies Vol. 29, No. 1, 2020, 189-216. Toward a (Sub)-Regionalization of South Korea’s Unification Policy – the Proposal of a Romantic Road for Gangwon Province Bernhard Seliger, Hyun-Ah Choi* 70 years after the start of the Korean War, the Korean Peninsula is still divided, and a peace regime is not in sight. The hopes of 2018, a year full of exciting summit diplomacy starting with the Winter Olympic Games in PyeongChang and culminating in terms of South-North relations in the Panmunjeom declaration of April 2018, have been dashed, and inter-Korean relations slid back to the familiar, but depressing pattern of stalemate and mutual recriminations. All initiatives taken as part of the Panmunjeom declaration, like the modernization and connection of railroad lines, are stalled or have failed. One reason for this might be that the approach taken for inter-Korean relations has always been highly centralized and focused on a few, large projects. These projects were prone to fail or were even, like in the case of the Iron Silk road, non-starters. The current debate to allow individual tourism is a reaction to overcome this centralized approach. Another important way to decentralize unification policies of South Korea is the sub-regionalization, i.e. the active involvement of provinces, counties and cities in unification policies. While there has been some precedent, like the mandarin shipments from Jeju province, the discretion for action by provinces or counties has always been very small. -

MEMBER REPORT Democratic People's Republic of Korea

MEMBER REPORT Democratic People’s Republic of Korea ESCAP/WMO Typhoon Committee 15th Integrated Workshop Vietnam 1-2 December 2020 Contents Ⅰ. Overview of tropical cyclones which have affected/impacted member’s area since the last Committee Session 1. Meteorological Assessment 2. Hydrological Assessment 3. Socio-Economic Assessment 4. Regional Cooperation Assessment Ⅱ. Summary of Progress in Priorities supporting Key Result Areas 1. Strengthening Typhoon Analyzing Capacity 2. Improvement of Typhoon Track Forecasting 3. Continued improvement of TOPS 4. Improvement of Typhoon Information Service 5. Effort for reducing typhoon-related disasters Ⅰ. Overview of tropical cyclones which affected/impacted member’s area since the last Committee Session 1. Meteorological Assessment DPRK is located in monsoon area of East-Asia, and often impacted by typhoon-related disasters. Our country was affected by five typhoons in 2020. Three typhoons affected directly, and two typhoons indirectly. (1) Typhoon ‘HAGPIT’(2004) Typhoon HAGPIT formed over southeastern part of China at 12 UTC on August 1. It continued to move northwestward and landed on china at 18 UTC on August 3 with the Minimum Sea Level Pressure of 975hPa and Maximum Wind Speed of 35m/s, and weakened into a tropical depression at 15 UTC. After whirling, it moved northeastward, and landed around peninsula of RyongYon at 18 UTC on August 5, and continued to pass through the middle part of our country. Under the impact of HAGPIT, accumulated rainfall over several parts of the middle and southern areas of our country including PyongGang, SePo, SinGye, and PyongSan County reached 351-667mm from 4th to 6th August with strong heavy rain, and average precipitation was 171mm nationwide. -

Democratic People's Republic of Korea

Operational Environment & Threat Analysis Volume 10, Issue 1 January - March 2019 Democratic People’s Republic of Korea APPROVED FOR PUBLIC RELEASE; DISTRIBUTION IS UNLIMITED OEE Red Diamond published by TRADOC G-2 Operational INSIDE THIS ISSUE Environment & Threat Analysis Directorate, Fort Leavenworth, KS Topic Inquiries: Democratic People’s Republic of Korea: Angela Williams (DAC), Branch Chief, Training & Support The Hermit Kingdom .............................................. 3 Jennifer Dunn (DAC), Branch Chief, Analysis & Production OE&TA Staff: North Korea Penny Mellies (DAC) Director, OE&TA Threat Actor Overview ......................................... 11 [email protected] 913-684-7920 MAJ Megan Williams MP LO Jangmadang: Development of a Black [email protected] 913-684-7944 Market-Driven Economy ...................................... 14 WO2 Rob Whalley UK LO [email protected] 913-684-7994 The Nature of The Kim Family Regime: Paula Devers (DAC) Intelligence Specialist The Guerrilla Dynasty and Gulag State .................. 18 [email protected] 913-684-7907 Laura Deatrick (CTR) Editor Challenges to Engaging North Korea’s [email protected] 913-684-7925 Keith French (CTR) Geospatial Analyst Population through Information Operations .......... 23 [email protected] 913-684-7953 North Korea’s Methods to Counter Angela Williams (DAC) Branch Chief, T&S Enemy Wet Gap Crossings .................................... 26 [email protected] 913-684-7929 John Dalbey (CTR) Military Analyst Summary of “Assessment to Collapse in [email protected] 913-684-7939 TM the DPRK: A NSI Pathways Report” ..................... 28 Jerry England (DAC) Intelligence Specialist [email protected] 913-684-7934 Previous North Korean Red Rick Garcia (CTR) Military Analyst Diamond articles ................................................ -

Download Shotlist

NEW Video from The UN World Food Programme Shows North Koreans Struggling From Effects of Drought and Floods: WFP News Video Release 19-Sep-2012 TRT: 3:41 :00-:30 Anju, DPRK Shot: 19Aug, 2012 200 women, mostly housewives, hauling mud in 5 hour shifts have been mobilized to build a dam protecting their corn fields from a flood damaged sewage system. :30-:46 Anju DPRK Shot: 19Aug, 2012 Ruined corn fields. Lack of rain damaged 40% of the spring harvest, now floods threaten the main fall harvest. :46-:55 GV’s moutains near Wonsan, DPRK Shot: 19Aug, 2012 The DPRK is mostly mountains . Only 1/5 of the country is arable. :55-1:04 GV’s Wonsan, DPRK Shot: 20Aug, 2012 1:04-1:34 Wonsan Pediatric Hospital Shot: 20Aug, 2012 Malnourished babies being treated. WFP supplies them with a special cereal fortified with milk powder, minerals and vitamins. 1:34-1:49 Wonsan, DPRK Shot: 20Aug, 2012 Wonsan secondary School. Revolutionary Studies class 1:49-2:04 Wonsan, DPRK Shot: 20Aug, 2012 Wonsan secondary School. Kim Gwang Song- 13- year old boy (very short and thin, looks like 8 years) At grade four. He has some hearing difficulty. He likes sports especially running. The subject he is most interested is the history, particularly the revolutionary history of Korea. He wants to be farmer when he grows up. He wants to do some good deeds for the father land 2:04-2:20 SOT Claudia vonRoehl Country Director WFP DPRK Shot: Pyongyang on 21Aug, 2012 “WFP is looking particularly after mothers and their young babies because they are in a moment of their life when they really need a special nutrition booster and we see this as our humanitarian task to help them at this very special moment in their life.” 2:20-2:34 Wonsan Elementary School Shot: 20Aug, 2012 School meals being prepared with WFP supplied wheat and rice that is made into noodles. -

S P E C I a L R E P O

S P E C I A L R E P O R T FAO/WFP CROP AND FOOD SECURITY ASSESSMENT MISSION TO THE DEMOCRATIC PEOPLE’S REPUBLIC OF KOREA 28 November 2013 FOOD AND AGRICULTURE ORGANIZATION OF THE UNITED NATIONS, ROME WORLD FOOD PROGRAMME, ROME This report has been prepared by Kisan Gunjal and Swithun Goodbody (FAO) and Siemon Hollema, Katrien Ghoos, Samir Wanmali, Krishna Krishnamurthy and Emily Turano (WFP) under the responsibility of the FAO and WFP Secretariats with information from official and other sources. The authors wish to acknowledge valuable contributions from Belay Gaga and Bui Bong (FAO) and Anna- Leena Rasanen, Xuerong Liu, Dawa Gyetse and Jennifer Rosenzweig (WFP). Since conditions may change rapidly, please contact the undersigned for further information if required. Liliana Balbi Kenro Oshidari Senior Economist, GIEWS, FAO Regional Director, WFP Fax: 0039-06-5705-4495 Fax: 0066-26554413 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] Please note that this Special Report is also available on the Internet as part of the FAO World Wide Web (www.fao.org ) at the following URL address: http://www.fao.org/giews/ The Special Alerts/Reports can also be received automatically by E-mail as soon as they are published, by subscribing to the GIEWS/Alerts report ListServ. To do so, please send an E-mail to the FAO-Mail- Server at the following address: [email protected] , leaving the subject blank, with the following message: subscribe GIEWSAlertsWorld-L To be deleted from the list, send the message: unsubscribe GIEWSAlertsWorld-L Please note that it is now possible to subscribe to regional lists to only receive Special Reports/Alerts by region: Africa, Asia, Europe or Latin America (GIEWSAlertsAfrica-L, GIEWSAlertsAsia-L, GIEWSAlertsEurope-L and GIEWSAlertsLA-L). -

Humanitarian Aid in Favour of Vulnerable Groups in DPRK

EUROPEAN COMMISSION DIRECTORATE-GENERAL FOR HUMANITARIAN AID - ECHO Humanitarian Aid Decision 23 02 01 Title: Humanitarian aid in favour of vulnerable groups in DPRK Location of operation: DEMOCRATIC PEOPLE'S REPUBLIC OF KOREA Amount of Decision: EUR 8,000,000 Decision reference number: ECHO/PRK/BUD/2006/01000 Explanatory Memorandum 1 - Rationale, needs and target population. 1.1. - Rationale: The protracted humanitarian crisis in the Democratic People's Republic of Korea (DPRK) is caused by a combination of the continuing decline of the economy and an inability of the Government to effectively redress the situation with appropriate development measures. The floods of the mid-1990s exposed the humanitarian magnitude of the fast deteriorating living conditions in the DPRK that resulted from the dissolution of its relationship with the former Soviet bloc economies after the ending of the Cold War. As a major catastrophe involving according to some sources up to an estimated 2 million casualties at that time, this crisis set off one of the biggest humanitarian aid operations in history. There is a growing consensus among the international aid agencies working in DPRK that the humanitarian situation has stabilized. The nutritional status of the population has levelled off to a degree of chronic malnutrition similar to levels found in several countries in South East Asia. Food security has been improving following an increase in agricultural production that came as a result of external support to inputs, adjustments to the cropping system, and increased cultivation of marginal land on slopes (although this does present concerns for the longer term). Exchanges of surpluses among the population have become somewhat easier since small-scale trade was again permitted following the introduction of a first, albeit very timid, economic reform package in 2002. -

The Wonsan–Mt. Kumgang International Tourist Zone

Trade & investment options in North Korea The Wonsan–Mt. Kumgang International Tourist Zone Rotterdam, June 2016 The Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK, also known as North Korea) finds itself at a new era of international economic cooperation, and it especially welcomes business with Europe. It is offering various products and services to export markets, while it is also in need for foreign investments. There are several sectors, including energy, agro business, shipbuilding, fishing, logistics, garments, tourism, animation and Information Technology, that can be considered for trade and investment. the new airport terminal of Pyongyang The Korean government is trying to attract a larger number of foreign tourists. There are several investment opportunities in the field of tourism, and an example is the the Wonsan – Mt. Kumgang International Tourist Zone. This zone includes areas of Wonsan, the Masikryong Ski Resort, Ullim Falls, Sokwang Temple, Thongchon and Mt. Kumgang. An introduction into the various investment projects related to this tourist zone is presented below; it is compiled by the Wonsan Zone Development Corporation of DPRK. We can be contacted in case you are interested in exploring this project in more detail. It is also possible for us to arrange investor visits to the Wonsan-Kumgang International Tourist Zone (we organise business missions to DPRK on a regular basis). For information Established in 1995, GPI Consultancy is a specialized Dutch consultancy firm in the field of offshore sourcing. It is involved in business missions to various Asian countries, including North Korea. For companies interested in working with North Korea, one of the immediate challenges is finding a suitable business partner, since collecting information is not easy. -

Overview Funding Document Vmay 2011 Protected

2011 THE UNITED NATIONS OVERVIEW OF NEEDS AND ASSISTANCE THE DEMOCRATIC PEOPLE’S REPUBLIC OF KOREA Preface The humanitarian work of the UN Country Team (UNCT) in DPRK involves five UN Agencies: FAO, UNFPA, UNICEF, WFP and WHO whilst a sixth Agency, UNDP, houses the UN Resident Coordinator’s Office. Difficulties in securing a steady financial support for humanitarian activities has led the UNCT to issue a monthly note to the Emergency Relief Coordinator in OCHA with the purpose of keeping current, the hardships the population faces on a daily basis. The UNCT has prepared a more comprehensive document - the Overview Funding Document for 2011 - as a tool to inform the international community about the current humanitarian issues in DPR Korea. It also addresses donors’ concerns regarding the UN Agencies’ ability to deliver increased assistance effectively. Substantive drafting processes for this document relied on data and analysis from the Thematic Groups which comprise all humanitarian partners including International NGOs. The focus of the humanitarian work of the agencies in DPR Korea is on mitigating the protracted crisis in the country through programmes which address the immediate food, health, water and sanitation, and educational needs. We in the UNCT are convinced that our engagement, maintenance of an in-country presence and full adherence to humanitarian principles have been positive factors in improving the situation for the people of DPR Korea and that this approach continues to be the best way to proceed. In particular the humanitarian and rehabilitation programmes implemented in the country during the last five years have, without doubt, achieved positive results for a great number of people in the country.