A Guide to Separation of Waste at Source

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Household Solid Waste Recycling Programme in Stellenbosch: Householders' Attitudes and Willingness Toparticip Ate

A HOUSEHOLD SOLID WASTE RECYCLING PROGRAMME IN STELLENBOSCH: HOUSEHOLDERS' ATTITUDES AND WILLINGNESS TOPARTICIP ATE MAFALLA E. MAKAU Thesis presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts at the University of Stellenbosch. Supervisor: Dr PH DE NECKER APRIL2006 Stellenbosch University http://scholar.sun.ac.za ii DECLARATION I; the undersigned. hereby. dcclm·\i that the W«k ¢Mtained ih tbl:s thesis is my own Qfiglnal work and that 1 have;: oot previously in Ita entirety or In part submitted it Bt any univorsit;y for a dagrec. Signature: Daw: Stellenbosch University http://scholar.sun.ac.za Ill ABSTRACT Municipal waste presents problems of pollution, health hazards and resource conservation. Household waste forms part of municipal solid waste that is a challenge to control due to its heterogeneity and diversity. The ever-filling landfills for the disposal of solid waste due to rapid population increase and urbanization call for urgent waste management strategies to reduce, reuse and recycle solid waste. In this study householders' attitudes, participation in recycling and willingness to participate in household solid waste recycling are investigated to design and implement a household solid waste recycling programme in Stellenbosch. Questionnaire survey data about the awareness of, attitudes towards, and participation in household waste recycling were analyzed using descriptive statistical methods in the STATISTICA V6 program. Results were displayed in frequency tables, bar charts, maps and pie charts. The same statistical program was used to fmd the relationship between the householders' willingness to participate in the household solid waste recycling programme, namely the Blue Bag Household Waste Recovery Programme (BBHWRP), and their socio-demographic and socio-economic characteristics. -

An Examination of Collection Mediums for Printed Paper and Packaging Waste

Thinking “Beyond the Box” – an examination of collection mediums for printed paper and packaging waste. Corresponding Author: Dr. Calvin Lakhan Prepared by: Waste Wiki@FES Faculty of Environmental Studies, York University 1 Contents Glossary of Terms.......................................................................................................................................... 2 Executive Summary ....................................................................................................................................... 3 1.0 Introduction ............................................................................................................................................ 3 2.0 Findings from broader literature review ................................................................................................ 4 2.1: Comparison of Bags, Boxes, and Carts ........................................................................................... 4 3.0 Materials and Methods ........................................................................................................................... 7 3.1 Research Stages and Data Preparation ............................................................................................... 8 4.0 Results and Discussion .......................................................................................................................... 10 4.1 Recycling System Performance ........................................................................................................ -

Recycling Is Not New to the Big ΠEarly History (1970 - 1990) Facility

Recycling is Not New to the Big Œ Early History (1970 - 1990) facility. All revenue from the sale of the sorted newspaper accrued to ENCOR to help offset the cost of conducting Recycling began in Omaha long before it was the their program. In 1988, 1,800 tons of newspapers were fashionable thing to do. During the winter of 1970-71 Mrs. recycled by ENCOR. Les Anderson, then chairman of the Governor’s Council In 1989 approximately 3,200 tons of newspaper were to Keep Nebraska Beautiful, began to make plans for the collected and recycled. With the market for newspaper collection of old glass containers and paper for recycling. being severely depressed, ENCOR asked to be released Although no U.S. city had tried glasphalt for paving, from their contract and were allowed to discontinue Mrs. Anderson knew several industries had tried it. She sorting and marketing newspaper. spoke with Omaha Public Works offi cials and received agreement to cooperate in the testing of glasphalt on In February 1990 the City began marketing the 15th Street, between Capitol and Dodge Streets. With the newspaper collected without a fi nal sort being performed help of many local companies and individuals, glass was at a cost of $10 per ton to the City. Bids, for collecting and collected, crushed and used in the test project in August marketing newspaper, opened in May, 1990 indicated that 1972. it was going to cost the City a minimum of $70 per ton to continue the newspaper program after December 31,1990. The Omaha World-Herald and Keep The decision was made to discontinue the separate Omaha Beautiful teamed up in 1973 collection and marketing of newspaper, after December, to start the fi rst curbside newspaper as the facility for sorting recyclables would be in place collection program. -

2018 Refuse & Recycling Survey Results

Refuse and Recycling Survey Q1 Name and Address Answered: 523 Skipped: 18 ANSWER CHOICES RESPONSES Name 99.04% 518 Company 0.00% 0 Address 99.24% 519 Address 2 0.00% 0 City/Town 99.43% 520 State/Province 0.00% 0 ZIP/Postal Code 0.00% 0 Country 0.00% 0 Email Address 0.00% 0 Phone Number 0.00% 0 1 / 62 Refuse and Recycling Survey Q2 Overall, how satisfied are you with the current quality of the refuse and recycling collection program in Western Springs? Answered: 540 Skipped: 1 Very satisfied Satisfied Neither satisfied no... Dissatisfied Very dissatisfied 0% 10% 20% 30% 40% 50% 60% 70% 80% 90% 100% ANSWER CHOICES RESPONSES Very satisfied 25.19% 136 Satisfied 40.00% 216 Neither satisfied nor dissatisfied 15.93% 86 Dissatisfied 15.19% 82 Very dissatisfied 3.70% 20 TOTAL 540 40 / 62 Refuse and Recycling Survey Q3 Overall, how would you rate your level of satisfaction with the current pricing options available for refuse and recycling services? Answered: 539 Skipped: 2 Very satisfied Satisfied Neither satisfied no... Dissatisfied Very dissatisfied 0% 10% 20% 30% 40% 50% 60% 70% 80% 90% 100% ANSWER CHOICES RESPONSES Very satisfied 10.58% 57 Satisfied 32.47% 175 Neither satisfied nor dissatisfied 30.06% 162 Dissatisfied 22.63% 122 Very dissatisfied 4.27% 23 TOTAL 539 41 / 62 Refuse and Recycling Survey Q4 The Village currently restricts container size for refuse collection to 33-gallon containers. Would you be interested in alternative container sizes for refuse? Answered: 533 Skipped: 8 Yes- 65 gallon container Yes- 95 gallon container No- I prefer the 33 gallo.. -

Blue Bag Recycling Flyer Generic 2018.10.Indd

RECYCLE MORE! Don’t just trash it, BLUE BAG it! Participate in the Blue Bag Recycling Program today! BUY Purchase any size sturdy blue recycling bags at local retailers or online. TIPS: • Drawstring bags are best. • Read the packaging and look for the word “RECYCLING” on Want to know more about how blue bag recycling works? Check the label. (Glad® and Husky® are the most common brands.) out our blog post Solving the Mystery of the Blue Bag. BAG IT www.grangernet.com/solving-the-mystery-of-the-blue-bag Place all clean recyclables into blue recycling bags. TIPS: • DON’T USE BLUE BAGS FOR TRASH! • No sorting required – recyclable materials can all hang out together in the same bag. • Empty and rinse all containers; break down boxes and bulky items. TIE IT Tie blue recycling bags and place with trash bags at the curb or in your personal cart on your collection day. TIPS: • Double tie bags for extra security. • Place your blue recycling bags either in your trash cart or at the curb next to your trash. • Remember to stay within your bag limit to avoid an extra charge. (Visit the Recycle & Waste For Your Home section of our website to learn what your bag limit is.) • Bag tag customers must use a bag tag on each blue bag. www.grangernet.com | 1-888-9GRANGER (1-888-947-2643) BLUE BAG RECYCLING GUIDE Your recycling collection is referred to as “single-stream” or “comingled” recycling. This means that all recyclables go into your blue bag together and do not need to be sorted. -

Twelve Factors Influencing Sustainable Recycling of Municipal Solid Waste

Michigan Technological University Digital Commons @ Michigan Tech Dissertations, Master's Theses and Master's Dissertations, Master's Theses and Master's Reports - Open Reports 2005 Twelve factors influencing sustainable ecyr cling of municipal solid waste in developing countries Alexis Manda Troschinetz Michigan Technological University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.mtu.edu/etds Part of the Civil and Environmental Engineering Commons Copyright 2005 Alexis Manda Troschinetz Recommended Citation Troschinetz, Alexis Manda, "Twelve factors influencing sustainable ecyr cling of municipal solid waste in developing countries ", Master's Thesis, Michigan Technological University, 2005. https://doi.org/10.37099/mtu.dc.etds/277 Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.mtu.edu/etds Part of the Civil and Environmental Engineering Commons TWELVE FACTORS INFLUENCING SUSTAINABLE RECYCLING OF MUNICIPAL SOLID WASTE IN DEVELOPING COUNTRIES By ALEXIS MANDA TROSCHINETZ A THESIS Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE IN ENVIRONMENTAL ENGINEERING MICHIGAN TECHNOLOGICAL UNIVERSITY 2005 Copyright © Alexis M. Troschinetz 2005 This thesis, “Twelve factors influencing sustainable recycling of municipal solid waste in developing countries," is hereby approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE IN ENVIRONMENTAL ENGINEERING. DEPARTMENT or PROGRAM: Civil and Environmental Engineering -Signatures- Thesis Advisor: __________________________________________ -

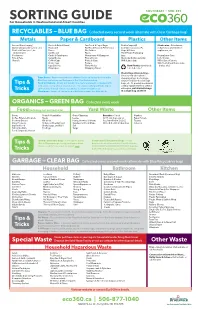

SORTING GUIDE for Households in Westmorland and Albert Counties

SORTING GUIDE For Households in Westmorland and Albert Counties RECYCLABLES – BLUE BAG Collected every second week (alternate with Clear Garbage bag) Metals Paper & Cardboard Plastics Other Items Aerosol Cans (empty) Books & Bristol Board Fast Food & Paper Bags Bottles (caps off ) Electronics – Calculators, Aluminum (pie plates, foil, etc.) Boxboard Fast Food Boxes & Pizza Boxes Containers (covers off ) cell phones, small kitchen Bottles & Cans (steel, tin Boxes File Folders Cups & Dishes appliances, etc. & aluminum) Cardboard Flyers Hard Plastic Packaging Containers Cards & Catalogues Newspaper & Magazines Jugs Frozen Juice Cans Pots & Pans Cereal Boxes Phone Books Medicine Bottles (empty) Lids, Covers Utensils Coff ee Cups Plates & Cups Milk & Juice Jugs Milk & Juice Cartons Drink Trays Posters Styrofoam (meat trays, cups, Egg Cartons Sticky Notes Hard Plastics numbered: plates, etc.) Envelopes Wrapping Paper 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 & 7 Plastic Bags (Clean & Dry) – Grocery and other plastic Pizza Boxes – Remove any crusts or le over cheese and place the box in the shopping bags, bread bags, Blue Recyclables bag and the paper in the Clear Garbage bag. clean re-sealable food storage Tips & Food Containers – Empty and quickly rinse metal and plastic containers with bags, etc. To prevent mechanical cold water; it only takes a second or two. As long as nothing will leak, drip or sorting equipment from getting Tricks spill out onto the rest of your recyclables, it’s clean enough for us! entangled, put all plastic bags Aluminum – Scrape off excess food and -

Markets and Politics in Urban Recycling: a Tale of Two Cities

WP-01-13 Markets and Politics in Urban Recycling: A Tale of Two Cities Allan Schnaiberg Department of Sociology Northwestern University Adam S. Weinberg Department of Sociology and Anthropology Colgate University David Pellow Department of Sociology and Ethnic Studies University of Colorado at Boulder Recycling: A Tale of Two Cities 2 Schnaiberg/Weinberg/Pellow May 10, 2001 Abstract Much contemporary environmental policymaking shifts our political focus away from our ecological goals, stressing instead the need to create "economically efficient" means to accomplish these goals. Social scientists have paid limited attention to the social distributive outcomes of such policymaking. Yet these outcomes of heightening attention to economic efficiencies affect the scale and intensity of political constituencies for environmental protection. In this Tale Of Two Cities, we trace this process of "markets over politics" and its impacts in the United States, Chicago, and its northern suburb of Evanston, Illinois, in the 1990s. Both cities constructed and implemented curbside recycling programs during this period. But the rationale, goals, and means of recycling were dramatically different in the two municipalities. Although both communities recruited unskilled labor for the actual sorting jobs, the Chicago facility initially offered a repressive and regressive mode of labor control, essentially reducing low-income workers to a day-labor contingent worker status. Recyclable diversion rates were extremely low for the wide diversity of materials collected. In contrast, Evanston offered both life-skills training to its workers, and assistance in getting employment at the end of their recycling jobs. Their recyclable diversion rates were quite high for the restricted materials they selected. -

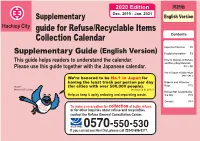

Guide for Refuse/Recyclable Items Collection Calendar

2020 Edition 英語版 Dec. 2019 - Jan. 2021 Supplementary English Version Hachioji City guide for Refuse/Recyclable Items Contents Hachioji City Collection Calendar Important Notices P2 Supplementary Guide (English Version) English description P3 How to Dispose of Refuse This guide helps readers to understand the calendar. and Recycling Materials Please use this guide together with the Japanese calendar. P4 〜 P8 How to Dispose of Bulky Refuse P9 〜 P11 We’re honored to be No.1 in Japan for having the least trash per person per day Diapers and Volunteer Bags P12 "Kururi", (for cities with over 500,000 people). Mascot of Recycling (measured in 2017) Refuse Not Accepted by Help us keep it up by reducing and separating waste. the City P13 Contact P14 P l ea in s s e e ou join pa r e us ra ffort To make a reservation for collection of bulky refuse, te to garbage. or for other inquiries about refuse and recyclables contact the Refuse General Consultation Center. If you cannot use Navi Dial, please call ☎042-696-5377. Non-burnable refuse Plastic bags for non-burnable refuse Please throw garbage in the designatedMetal garbage bags!! Garbage bags that are not for Hachioji will not be collected Burnable refusePlastic bags for burnable refuse Glass Used lunch box containers Kitchen refuse Plastic toys Earthenware Cigarettes For more information, please refer to page 6. Shoes / bags / belts Please purchase garbage bags for Stationeries combustible trash and incombustible trash 2 収 集 カ レ ン ダ ー For more information, please refer to page 5.2020年版 P2 2019年12月〜2021年1月 P13 at a supermarket or convenience store. -

BAG the PLASTIC BAG’ Questions and Answers

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Contact: Mona Astra Liss, IKEA Corporate PR Director ~ [email protected] ~ 610.834.0180 ext. 5852 Charly Rok, Lippe Taylor PR, [email protected] ~ 212.598.4400 ext. 155 IKEA ‘BAG THE PLASTIC BAG’ Questions and Answers 1. How does the IKEA “BAG THE PLASTIC BAG” program work? This program is about changing consumer behavior and reducing plastic bag waste and litter. Beginning on March 15th, IKEA will no longer offer customers free plastic bags at checkout. Customers can choose to buy a plastic bag for five cents ,bring their own bag from home, use no bag, or purchase IKEA’s iconic, reusable ‘blue bag;’ for 59 cents. The goal is to cut plastic bag use in half at IKEA, from 70 million bags per year to 35 million, or even fewer. 2. Why is IKEA charging for shopping bags when they were previously given away in their stores and still are in other retail outlets? IKEA believes that part of caring for the environment is finding ways to do more with less. In that spirit, IKEA wants to help move customers away from using unnecessary plastic bags. People in the United States throw away about 100 billion plastic shopping bags each year1. Some are recycled, but most never get a second use; they are simply thrown away as garbage. Changing habits is hard, but IKEA believes that by working together, we can all make a difference. 3. Why are plastic bags a problem? Plastic bags strangle our planet. They are a stream of waste and litter our environment. -

Download Recycling Handout

Dallas County Home Chemical Collection Center A Free Disposal Service for Residents of: Addison - http://wv/w.addisontx.qov/ Dallas - http://www.daiiascitvhail.com/ DeSoto - http://www.desototexas.gov/ Duncanville - http://www.ci.duncanville.tx.us/ Fanners Branch - hUp://www.farmersbranch.irifo/ Garland - http://www.ci.gariand.tx.us/ Highland Park - http://vwvw.hptx.org/ Irving - htt,p://ww¥v?.ciivofirvinQ.org/ Mesquite ~ htip://www.citvoftTiesquite.com/ Richardson - http://www.cor.net/ Rowlett • www, ci. rowlett.tx.us/rowiett/ Sachse - http://www.cityofsachse.corn/ Seagoville - http://www.seagoville.us/ Sunnyvale - http://www.townofsunnyya.l.e,orc|/ University Park - http://www.uptexas.org and unincorporated areas of Dallas County Bring a driver's license and water bill or other utility bill as proof of current address. Residents of all other cities pay a minimum $95.00 waste management fee. Location: Hours of Operation: 11234 Piano Road Tuesdays: 9:00 a.m. - 7:30 p.m. Dallas, Texas 75243 Wednesdays: 8:30 a.m. - 5:00 p.m. 214.553.1765 Thursdays: 8:30 a.m. - 5:00 p.m. 2nd and 4th Saturdays of each month: See MAPSCO 28-A 9:00 a.m. - 3:00 p.m. Or go to Mapguest.com Closed every Sunday, Monday, and Friday 2015 Dallas County & HHW Holiday Closures Martin Luther King Monday January 19'" Memorial Day Monday May 25* Independence Day Friday July 3rd Labor Day Monday September 7* Thanksgiving Holiday Thursday & Friday November 26"' & 27*' Christmas Holiday V\.'ednesday, Thursday & Friday December 23"^, 24''" & 25* 2015 HHW Saturday Closures I May 23''-^ November 28* December 26* Directions: From 635, go north one mile on Piano Rd. -

Energy Implications of Glass-Container Recycling

ANUESD-18 N REUTP-430-5703 A Joint Effort • ••·-· •• Energy Systems Division ·-· National Renewable Argonne National Laboratory • Energy Laboratory Operated by the University of Chicago Operated by Midwest Research Institute for the U.S. Department of Energy for the U.S. Department of Energy under Contract W-31-1 09-Eng-38 under Contract DE-AC02-83-CH1 0093 Authors: L. L. Gaines Technical Monitor: Philip B. Shepherd M. M. Mintz Argonne National Laboratory and the National Renewable Energy Laboratont are part of the national laboratory system to the U.S. Department of En• ANUESD-18 NREUTP-430-5703• UC Category: 249 • DE94000288 L.L. Gaines & M.M. Mintz Argonne National Laboratory Argonne, Illinois Technical Monitor: Philip B. Shepherd A Joint Effort .. ••·-· •• Energy Systems Division ·-· National Renewable Argonne National Laboratory • Energy Laboratory Operated by the University of Chicago Operated by Midwest Research Institute for the U.S. Department of Energy for the U.S. Department of Energy under Contract W-31 -1 09-Eng-38 under Contract DE-AC02-83-CH1 0093 This report was prepared under Task #WM41 .1 01 0 and Subcontract #DA-1 -1 1157-1 March, 1994 NOTICE NOTICE: This report was prepared as an account of work sponsored by an agency of the United States government. Neither the United States government nor any agency thereof, nor any of their employees, makes any warranty, express or implied, or assumes any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of any information, apparatus, product, or processdisclosed, or represents that its use would not infringe privately owned rights.