The High Tide in Jiangsu: a Perspective from Local Sources of the Time*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BANK of JIANGSU CO., LTD.Annual Report 2015

BANK OF JIANGSU CO., LTD.Annual Report 2015 Address:No. 26, Zhonghua Road, Nanjing, Jiangsu Province, China PC:210001 Tel:025-58587122 Web:http://www.jsbchina.cn Copyright of this annual report is reserved by Bank of Jiangsu, and this report cannot be reprinted or reproduced without getting permission. Welcome your opinions and suggestions on this report. Important Notice I. Board of Directors, Board of Supervisors as well as directors, supervisors and senior administrative officers of the Company warrant that there are no false representations or misleading statements contained in this report, and severally and jointly take responsibility for authenticity, accuracy and completeness of the information contained in this report. II. The report was deliberated and approved in the 19th board meeting of the Third Board of Directors on February 1, 2016. III. Except otherwise noted, financial data and indexes set forth in the Annual Report are consolidated financial data of Bank of Jiangsu Co., Ltd., its subsidiary corporation Jiangsu Danyang Baode Rural Bank Co., Ltd. and Suxing Financial Leasing Co., Ltd. IV. Annual financial report of the Company was audited by BDO China Shu Lun Pan Certified Accountants LLP, and the auditor issued an unqualified opinion. V. Xia Ping, legal representative of the Company, Ji Ming, person in charge of accounting work, and Luo Feng, director of the accounting unit, warrant the authenticity, accuracy and integrality of the financial report in the Annual Report. Signatures of directors: Xia Ping Ji Ming Zhu Qilon Gu Xian Hu Jun Wang Weihong Jiang Jian Tang Jinsong Shen Bin Du Wenyi Gu Yingbin Liu Yuhui Yan Yan Yu Chen Yang Tingdong Message from the Chairman and service innovation, made great efforts to risk prevention and control, promoted endogenous growth, improved service efficiency and made outstanding achievements. -

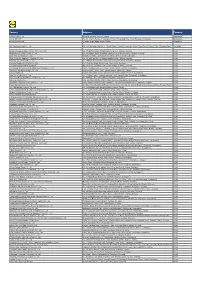

Factory Address Country

Factory Address Country Durable Plastic Ltd. Mulgaon, Kaligonj, Gazipur, Dhaka Bangladesh Lhotse (BD) Ltd. Plot No. 60&61, Sector -3, Karnaphuli Export Processing Zone, North Potenga, Chittagong Bangladesh Bengal Plastics Ltd. Yearpur, Zirabo Bazar, Savar, Dhaka Bangladesh ASF Sporting Goods Co., Ltd. Km 38.5, National Road No. 3, Thlork Village, Chonrok Commune, Korng Pisey District, Konrrg Pisey, Kampong Speu Cambodia Ningbo Zhongyuan Alljoy Fishing Tackle Co., Ltd. No. 416 Binhai Road, Hangzhou Bay New Zone, Ningbo, Zhejiang China Ningbo Energy Power Tools Co., Ltd. No. 50 Dongbei Road, Dongqiao Industrial Zone, Haishu District, Ningbo, Zhejiang China Junhe Pumps Holding Co., Ltd. Wanzhong Villiage, Jishigang Town, Haishu District, Ningbo, Zhejiang China Skybest Electric Appliance (Suzhou) Co., Ltd. No. 18 Hua Hong Street, Suzhou Industrial Park, Suzhou, Jiangsu China Zhejiang Safun Industrial Co., Ltd. No. 7 Mingyuannan Road, Economic Development Zone, Yongkang, Zhejiang China Zhejiang Dingxin Arts&Crafts Co., Ltd. No. 21 Linxian Road, Baishuiyang Town, Linhai, Zhejiang China Zhejiang Natural Outdoor Goods Inc. Xiacao Village, Pingqiao Town, Tiantai County, Taizhou, Zhejiang China Guangdong Xinbao Electrical Appliances Holdings Co., Ltd. South Zhenghe Road, Leliu Town, Shunde District, Foshan, Guangdong China Yangzhou Juli Sports Articles Co., Ltd. Fudong Village, Xiaoji Town, Jiangdu District, Yangzhou, Jiangsu China Eyarn Lighting Ltd. Yaying Gang, Shixi Village, Shishan Town, Nanhai District, Foshan, Guangdong China Lipan Gift & Lighting Co., Ltd. No. 2 Guliao Road 3, Science Industrial Zone, Tangxia Town, Dongguan, Guangdong China Zhan Jiang Kang Nian Rubber Product Co., Ltd. No. 85 Middle Shen Chuan Road, Zhanjiang, Guangdong China Ansen Electronics Co. Ning Tau Administrative District, Qiao Tau Zhen, Dongguan, Guangdong China Changshu Tongrun Auto Accessory Co., Ltd. -

Transmissibility of Hand, Foot, and Mouth Disease in 97 Counties of Jiangsu Province, China, 2015- 2020

Transmissibility of Hand, Foot, and Mouth Disease in 97 Counties of Jiangsu Province, China, 2015- 2020 Wei Zhang Xiamen University Jia Rui Xiamen University Xiaoqing Cheng Jiangsu Provincial Center for Disease Control and Prevention Bin Deng Xiamen University Hesong Zhang Xiamen University Lijing Huang Xiamen University Lexin Zhang Xiamen University Simiao Zuo Xiamen University Junru Li Xiamen University XingCheng Huang Xiamen University Yanhua Su Xiamen University Benhua Zhao Xiamen University Yan Niu Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention, Beijing City, People’s Republic of China Hongwei Li Xiamen University Jian-li Hu Jiangsu Provincial Center for Disease Control and Prevention Tianmu Chen ( [email protected] ) Page 1/30 Xiamen University Research Article Keywords: Hand foot mouth disease, Jiangsu Province, model, transmissibility, effective reproduction number Posted Date: July 30th, 2021 DOI: https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-752604/v1 License: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Read Full License Page 2/30 Abstract Background: Hand, foot, and mouth disease (HFMD) has been a serious disease burden in the Asia Pacic region represented by China, and the transmission characteristics of HFMD in regions haven’t been clear. This study calculated the transmissibility of HFMD at county levels in Jiangsu Province, China, analyzed the differences of transmissibility and explored the reasons. Methods: We built susceptible-exposed-infectious-asymptomatic-removed (SEIAR) model for seasonal characteristics of HFMD, estimated effective reproduction number (Reff) by tting the incidence of HFMD in 97 counties of Jiangsu Province from 2015 to 2020, compared incidence rate and transmissibility in different counties by non -parametric test, rapid cluster analysis and rank-sum ratio. -

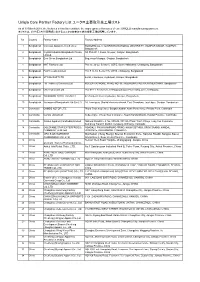

Uniqlo Core Partner Factory List ユニクロ主要取引先工場リスト

Uniqlo Core Partner Factory List ユニクロ主要取引先工場リスト As of 30 March 2018, the factories in this list constitute the major garment factories of core UNIQLO manufacturing partners. 本リストは、2018年3月30日時点におけるユニクロ主要取引先の縫製工場を掲載しています。 No. Country Factory Name Factory Address 1 Bangladesh Colossus Apparel Limited unit 2 MOGORKHAL, CHOWRASTA NATIONAL UNIVERSITY, GAZIPUR SADAR, GAZIPUR, Bangladesh 2 Bangladesh Crystal Industrial Bangladesh Private SA Plot-2013, Kewa, Sreepur, Gazipur, Bangladesh Limited. 3 Bangladesh Ever Smart Bangladesh Ltd. Begumour Mirzapur, Gazipur, Bangladesh 4 Bangladesh NHT Fashions Ltd. Plot no. 20-22, Sector-5, CEPZ, South Halishahar, Chittagong, Bangladesh 5 Bangladesh Pacific Jeans Limited Plot # 14-19, Sector # 5, CEPZ, Chittagong, Bangladesh 6 Bangladesh STYLECRAFT LTD 42/44, Chandona, Joydebpur, Gazipur, Bangladesh 7 Bangladesh TM Textiles & Garments Ltd. MOUZA-KASHORE, WARD NO.-06, HOBIRBARI,VALUKA,MYMENSHING, Bangladesh 8 Bangladesh Universal Jeans Ltd. Plot 09-11, Sector 6/A, Chittagong Export Processing Zone, Chittagong 9 Bangladesh YOUNGONES BD LTD UNIT-II 42 (3rd & 4th floor) Joydevpur, Gazipur, Bangladesh 10 Bangladesh Youngones(Bangladesh) Ltd.(Unit-2) 24, Laxmipura, Shohid chan mia sharak, East Chandona, Joydebpur, Gazipur, Bangladesh 11 Cambodia CAMBO KOTOP LTD. Phum Trapeang Chrey, Sangkat Kakab, Khan Porsenchey, Phnom Penh, Cambodia. 12 Cambodia Cambo Unisoll Ltd. Seda village, Vihear Sour Commune, Ksach Kandal District, Kandal Province, Cambodia 13 Cambodia Golden Apparel (Cambodia) Limited National Road No. -

Spatial and Temporal Evaluation of Ecological Footprint Intensity of Jiangsu Province at the County-Level Scale

International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health Article Spatial and Temporal Evaluation of Ecological Footprint Intensity of Jiangsu Province at the County-Level Scale Decun Wu 1 and Jinping Liu 2,* 1 School of Public Administration and Sociology, Jiangsu Normal University, Xuzhou 221116, China; [email protected] 2 School of Economics and Management, China University of Mining and Technology, Xuzhou 221116, China * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 10 September 2020; Accepted: 23 October 2020; Published: 26 October 2020 Abstract: Due to the high ecological pressure that exists in the process of rapid economic development in Jiangsu Province, it is necessary to evaluate its ecological footprint intensity (EFI). This article focuses on ecological footprint intensity analysis at the county scale. We used county-level data to evaluate the spatial distributions and temporal trends of the ecological footprint intensity in Jiangsu’s counties from 1995 to 2015. The temporal trends of counties are divided into five types: linear declining type, N-shape type, inverted-N type, U-shape type and inverted-U shape type. It was discovered that the proportions of the carbon footprint intensity were maintained or increased in most counties. Exploratory spatial data analysis shows that there was a certain regularity of the EFI spatial distributions, i.e., a gradient decrease from north to south, and there was a decline in the spatial heterogeneity of EFI in Jiangsu’s counties over time. The global Moran’s index (Moran’s I) and local spatial association index (LISA) are used to analyze both the global and local spatial correlation of EFIs among counties of Jiangsu Province. -

Multiobjective Optimization of Sustainable WCO for Biodiesel Supply Chain Network Design

Hindawi Discrete Dynamics in Nature and Society Volume 2021, Article ID 6640358, 16 pages https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/6640358 Research Article Multiobjective Optimization of Sustainable WCO for Biodiesel Supply Chain Network Design Nana Geng 1 and Yixiang Sun 2 1Nanjing University of Posts and Telecommunications, Nanjing 210023, China 2Nanjing University of Aeronautics and Astronautics, Nanjing 211106, China Correspondence should be addressed to Yixiang Sun; [email protected] Received 19 December 2020; Revised 18 February 2021; Accepted 26 February 2021; Published 9 March 2021 Academic Editor: Tingsong Wang Copyright © 2021 Nana Geng and Yixiang Sun. ,is is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Bioenergy is attracting more attention worldwide due to its environmental and economic benefits. ,e design of a feasible biodiesel supply chain network can effectively improve the production and use of biodiesel and then further promote the development of the biodiesel industry. As an easy recyclable material with high yield, kitchen waste has a good prospect and can solve public health and safety problems. ,is paper takes the kitchen waste producing biodiesel as the object to design and optimize the biodiesel supply chain in order to improve the sustainable development of biodiesel industry and the operational efficiency of the biodiesel supply chain. By designing a sustainable biodiesel supply chain model under defined conditions, it proposes strategic and tactical decisions related to location, production, inventory, and distribution within multiple planning cycles. In order to effectively solve the model, a Pareto optimal NSGAII heuristic algorithm is proposed and applied to a practical case study of restaurants in Jiangsu Province. -

Jiangsu Yanghe Distillery Co., Ltd. 2020 Annual Report April 2021

2020 Annual Report of Jiangsu Yanghe Distillery Co., Ltd. Jiangsu Yanghe Distillery Co., Ltd. 2020 Annual Report April 2021 1 2020 Annual Report of Jiangsu Yanghe Distillery Co., Ltd. Section I Important Statements, Contents and Definitions The board of directors, board of supervisors, directors, supervisors and senior management of Jiangsu Yanghe Brewery Co., Ltd. (hereinafter referred to as the Company) hereby guarantee that the information presented in this report is free of any false records, misleading statements or material omissions, and shall individually and together be legally liable for truthfulness, accuracy and completeness of its contents. Mr. Zhang Liandong, responsible person for the Company, Mr. Yin Qiuming, responsible person for accounting affairs and Mr. Zhao Qike, responsible person for accounting department (accounting supervisor) have warranted that the financial statements in this report are true, accurate and complete. All directors attended the board meeting to review this report. The future plans and some other forward-looking statements mentioned in this report shall not be considered as virtual promises of the Company to investors. Investors and people concerned should maintain adequate risk awareness and understand the difference between plans, predictions and promises. Investors are kindly reminded to pay attention to possible investment risks. In the annual report, the possible risks in the operation of the Company are described in detail (see 9.Outlook for the future development of the Company in Section -

World Bank Document

'~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~5-__\ KM GolderAssociates Inc. 200 UnionBoulevard. Suite 500 . Go1der Lakewood,CO USA80228 Telephone (303)980-0540 so Fox (303)985-2080 E-231 Public Disclosure Authorized ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT FOR EAST CHINA (JIANGSIJ) 500 kV TRANSMISSION LINE PROJECT Public Disclosure Authorized Preparedfor: East China Electric Power Group Corp. 201 Nanjing Road (E.) Shanghai 200002 PeoplesRepublic of China Preparedby: In Association with: Public Disclosure Authorized GolderAssociates Inc. Nanjing EnvironmentalProtection Research 200 UnionBlvd., Suite 500 Institute, Ministry of Electric Power Lakewood, Colorado 80228 10 PudongRoad Pukou, Nanjing PeoplesRepublic of China Distribution: / 3 copies - East China Electric Power Group Corp. Public Disclosure Authorized 3 copies - World Bank 1 copy - Jeanne Maltby 3 copies - Golder Associates Inc. May 18, 1998 973-2290.004 n'CIPCC iM1 Al MTOPI IA C'ANIArIA C-rDlAAtAIV Ul IKI(2AfV ITAIV CAA/tIr-IN I IMITEI- VIlr\1-1A I IkIIlTEn CTATr May 1998 -i- 973-2290.004 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................. ES-1 1.0 INTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND ..................................................... 1 1.1 Environmental Scope, Methodology, and Approach ...................................2 1.2 Environm ental Legislation, Regulations, and CGuidelines............................. 4 1.2.1 Chinese Legal and Regulatory Framework .................... ................. 4 1.2.1.1 Government of PRC ..................................................... 6 1.2.1.2 -

Transition to a Green Economy in China's Jiangsu Province

TRANSITION TO A GREEN ECONOMY IN CHINA’S JIANGSU PROVINCE A STOCKTAKING REPORT Copyright © United Nations Environment Programme, 2016 The report is published as part of the Partnership for Action on Green Economy (PAGE) – an initiative by the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), the International Labour Organization (ILO), the United Nations Development Programme, the United Nations Industrial Development Organization (UNIDO) and the United Nations Institute for Training and Research (UNITAR). This publication may be reproduced in whole or in part and in any form for educational or non-profit purposes without special permission from the copyright holder, provided acknowledgement of the source is made. UNEP would appreciate receiving a copy of any publication that uses this publication as a source. No use of this publication may be made for resale or for any other commercial purpose whatsoever without prior permission in writing from the United Nations Environment Programme. Citation PAGE (2016), Transition to a Green Economy in China’s Jiangsu Province: A Stocktaking Report Disclaimer The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the United Nations Environment Programme concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Moreover, the views expressed do not necessarily represent the decision or the stated policy of the United Nations Environment Programme, nor does citing of trade names or commercial processes constitute endorsement. UNEP promotes environmentally sound Cover photos: practices globally and in its © Tian Yongjun – © Karl Johaentges – © Robert Harding own activities. -

ACCASETTE GARMENT CO LTD Cambodia National Road No 3, Phnom Penh City Apparel 1000-3000 CO

Strategic Contractors Parent HBI Factory Name Country Address Product Type Employees HAND SEVEN INTERNATIONAL ENT. ACCASETTE GARMENT CO LTD Cambodia National Road No 3, Phnom Penh City Apparel 1000-3000 CO. LTD. | HAND SEVEN INTERNATIONAL ENT. ACCASETTE GARMENT VIETNAM CO LTD Vietnam One Part CN18 N2 Street & 6 Street Song Than 3 Industrial Zone, Phu Tan Ward, Thu Apparel 1000-3000 CO. LTD. | Dau Mot City Best Corporation Private Limited | ALPHA APPARELS India 106/1 Avinashi Road Lpt Opp Arasurpo, Coimbatore Apparel <1000 DAIWABO NEU CO. LTD. | ANHUI NEWJIALE GARMENT CO China 318 National Road Wenchang ToWn, Xuancheng City, Anhui Province Apparel <1000 ZXY INTERNATIONAL FZCO | Anlima Textile Limited Bangladesh Karnapara Savar, Dhaka 12090 Bangladesh Apparel 1000-3000 APEX LINGERIE LIMITED APEX LINGERIE LIMITED Bangladesh MOUZA-CHANDURA GAZIPUR, Bangladesh Apparel >3000 APEX TEXTILE PRINTING MILLS APEX TEXTILE PRINTING MILLS LIMITED Bangladesh Biman Bhaban 5th Floor Chandora Kailakoir, Gazipur Apparel >3000 LIMITED SHK CO.LTD. | APPARELTECH VINH LOC GARMENT EXPORT CO Vietnam Vinh Long Commune Vinh Loc District Thanh Hoa Province, Vinh Loc, Thua Thien- Apparel >3000 LTD Hue MARQUIS IMPEX PTE. LTD. |Best BEST INTERNATIONAL GAREMENTS PLC Ethiopia Shed No 38, HaWassa Industrial Park HaWassa SNPPR Region Apparel <1000 Corporation Private Limited | BOGART LINGERIE LTD BOGART LINGERIE SHENZHEN LTD China No28-29 Building No3 Shenzhen, China Apparel 1000-3000 HANSAE CO. LTD. | Branch of Hanoi Textile and Garment Joint Stock CorporationVietnam Nam Giang Inderstrial Zone Nam Dan, 25110 Vietnam Apparel 1000-3000 DAMOST CORP LTD | Chaohu Galaxy Vegas Textile China No 8, Jinchao Avenue, Heifei City, Anhui Apparel <1000 MIDAS GARMENT ENTERPRISE LTD TaiWan NO 36 SHINGUNG FIRST RD TAINJUNG, TaiWan Apparel <1000 (HQ) |MIDAS GARMENT ENTERPRISE LTD. -

Subsidy Programs

SUBSIDIES REQUEST FROM THE UNITED STATES TO CHINA PURSUANT TO ARTICLE 25.10 OF THE AGREEMENT The following communication, dated 15 April 2016, is being circulated at the request of the Delegation of the United States. _______________ In the report that it prepared for China's most recent Trade Policy Review, held in July 2014, the Secretariat included information that it had uncovered on 30 support programs for China's fisheries sector.1 The Secretariat's Report noted that China had not notified any of these support programs to the Committee on Subsidies and Countervailing Measures (Committee) and that China could not verify any of the information provided to it by the Secretariat. During the ensuing Trade Policy Review meetings, China responded to Members' questions about these support programs by stating that it needed more time to identify and verify information regarding these support programs. In April of last year, the United States submitted questions to China with respect to these programs and other fishery support measures the United States had uncovered through its own efforts.2 Once again, despite its obligation under Article 25.9 of the Agreement to provide answers "as quickly as possible and in a comprehensive manner", China to date has not meaningfully responded to the United States' request and has refused repeated requests to meet bilaterally to discuss the issue, and the issue of subsidy notifications more generally. In November of last year, China submitted its latest subsidy notification covering the period 2009 through 2014.3 In this notification, China did not include: (1) any of the fishery subsidy programs identified in China's 2014 TPR report, (2) any of the additional measures identified by the United States in its Article 25.8 submission or (3) any of the fisheries subsidies measures identified in the 2014 Article 25.10 submission of the United States4. -

World Bank Document

Public Disclosure Authorized ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT OF THE YANGCHENG TO HlJAIYIN 500 kV POWER TRANSMISSION l'ROJECT Public Disclosure Authorized V.i.. 3 Public Disclosure Authorized Jiangsu Provincial Electric Power Company No. 20 West Beijing Road Nanjing, Jiangsu Province People's Republic of China October 1997 Public Disclosure Authorized Table of Contents Pages 0. Executive summary 0-0 1. Introduction and background 1-1 I.1 The necessity of 500kV power transmission project construction 1-2 41.2The basic of environmental impact assessment for 1-2 500kV power transmission project 2. Project description 2-1 2.1 The route and composition of power transmission lines 2-1 2.2 Svitchyard. substation 2-2 2.3 power transmission line 2-2 2.4 Yellow river crossing 2-4 3. Environmental background status 3 3.1INatural environment 3-1 3.2 Ecological environment 3-3 3.3 Noise level 3-4 3.4 Electric field level 3-5 3.5 Social economic environment and living quality environment 3-5 4. Construction periiod environmental impact 4-1 4.1 Environmental impact identification 4-1 4.2 The impact on natural environment 4-1 4.3 Impact on ecological environment 4-4 4.4 Impact on social environment 4-6 4.5 Impact on living quality environment 4-8 5. Operation period environmental impact 5-1 5.1 Environmental impact identification 5-1 5.2 Impact on natural environment 5-1 5.3 Impact on ecological environment 5-3 5.4 Impact on social environment 5-5 5.5 Impact on living environment 5-8 6.