Chapter Five Directors

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Competing Interests in the Corporate Opportunity Doctrine Pat K

NORTH CAROLINA LAW REVIEW Volume 67 | Number 2 Article 5 1-1-1989 Competing Interests in the Corporate Opportunity Doctrine Pat K. Chew Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.unc.edu/nclr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Pat K. Chew, Competing Interests in the Corporate Opportunity Doctrine, 67 N.C. L. Rev. 435 (1989). Available at: http://scholarship.law.unc.edu/nclr/vol67/iss2/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Carolina Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in North Carolina Law Review by an authorized administrator of Carolina Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. COMPETING INTERESTS IN THE CORPORATE OPPORTUNITY DOCTRINE PAT K. CHEWt The corporateopportunity doctrinegoverns disputes that arise when a corporatefiduciary pursues a business opportunity that the corporation claims belongs to the corporation. Professor Chew identifies and evalu- ates the competing policy interests triggered by these disputes, traces the evolution of the corporate opportunity doctrine and examines the tradi- tional tests and emerging models for resolving such disputes. Professor Chew concludes that the traditionaland emerging tests inadequately protect legitimate individual and societal interests, and explains the im- plications of this deficiency. Finally, Professor Chew proposes an alter- native means for resolution of corporate opportunity disputes. She recommends express negotiations between corporations and fiduciaries on their respective rights,or, absent such negotiations,a heightenedjudi- cial recognition of the parties' reasonable expectations in creating their business relationship. I. INTRODUCTION Joe joined the corporation when it was just getting started. Although he was not offered any stock ownership, he liked and respected the family that owned the business. -

Understanding Maryland's Business Judgment Rule

File: sharfmanfinalmacro.doc Created on: 4/18/2006 5:07 PM Last Printed: 5/20/2006 5:17 PM Understanding Maryland’s Business Judgment Rule Bernard S. Sharfman1 I. INTRODUCTION The “Business Judgment Rule” (“BJR”) is a common law stan- dard of judicial review.2 The BJR is applied by the courts to favor the actions of corporate managers.3 According to Henry Manne, a leading commentator on corporate law, the BJR protects from ju- dicial review “honest if inept business decisions” made by corpo- rate managers.4 By accomplishing this strategic objective, the BJR tries to obtain its ultimate goal - preventing courts from exer- cising regulatory authority over corporate management.5 The creation of the BJR as a means of obtaining this goal is a direct product of the time period in which it originated. The BJR first appeared in the 19th century, a time when there was a fear of gov- ernment regulation. Since then, the BJR has been used by the courts as a means to avoid the exercise of regulatory authority over corporations.6 1. Bernard Sharfman is a member of the DC and Maryland bars and a Class of 2000 graduate of Georgetown University Law Center. This article is dedicated to Mr. Sharfman’s wife, Susan David, for without her encouragement and editorial comments this article would never have been completed. Mr. Sharfman would like to thank Joseph Hinsey, H. Douglas Weaver Professor of Business Law, Emeritus, at the Harvard University Graduate School of Business Administration and James J. Hanks, Jr., Partner, Venable LLP and the author of Maryland Corporate Law for their helpful comments and insights. -

Monitoring the Duty to Monitor

Corporate Governance WWW. NYLJ.COM MONDAY, NOVEMBER 28, 2011 Monitoring the Duty to Monitor statements. As a result, the stock prices of Chinese by an actual intent to do harm” or an “intentional BY LOUIS J. BEVILACQUA listed companies have collapsed. Do directors dereliction of duty, [and] a conscious disregard have a duty to monitor and react to trends that for one’s responsibilities.”9 Examples of conduct HE SIGNIFICANT LOSSES suffered by inves- raise obvious concerns that are industry “red amounting to bad faith include “where the fidu- tors during the recent financial crisis have flags,” but not specific to the individual company? ciary intentionally acts with a purpose other than again left many shareholders clamoring to T And if so, what is the appropriate penalty for the that of advancing the best interests of the corpo- find someone responsible. Where were the direc- board’s failure to act? “Sine poena nulla lex.” (“No ration, where the fiduciary acts with the intent tors who were supposed to be watching over the law without punishment.”).3 to violate applicable positive law, or where the company? What did they know? What should they fiduciary intentionally fails to act in the face of have known? Fiduciary Duties Generally a known duty to act, demonstrating a conscious Obviously, directors should not be liable for The duty to monitor arose out of the general disregard for his duties.”10 losses resulting from changes in general economic fiduciary duties of directors. Under Delaware law, Absent a conflict of interest, claims of breaches conditions, but what about the boards of mort- directors have fiduciary duties to the corporation of duty of care by a board are subject to the judicial gage companies and financial institutions that and its stockholders that include the duty of care review standard known as the “business judgment had a business model tied to market risk. -

Addressing Duty of Loyalty Parameters in Partnership Agreements: the More Is More Approach

Athens Journal of Law XY Addressing Duty of Loyalty Parameters in Partnership Agreements: The More is More Approach * By Thomas P. Corbin Jr. In drafting a partnership agreement, a clause addressing duty of loyalty issues is a necessity for modern partnerships operating under limited or general partnership laws. In fact, the entire point of forming a limited partnership is the recognition of the limited involvement of one of the partners or perhaps more appropriate, the extra-curricular enterprises of each of the partners. In modern operations, it is becoming more common for individuals to be involved in multiple business entities and as such, conflict of interests and breaches of the traditional and basic rules on duty of loyalty such as those owed by one partner to another can be nuanced and situational. This may include but not be limited to affiliated or self-interested transactions. State statutes and case law reaffirm the rule that the duty of loyalty from one partner to another cannot be negotiated completely away however, the point of this construct is to elaborate on best practices of attorneys in the drafting of general and limited partnership agreements. In those agreements a complete review of partners extra-partnership endeavours need to be reviewed and then clarified for the protection of all partners. Liabilities remain enforced but the parameters of what those liabilities are would lead to better constructed partnership agreements for the operation of the partnership and the welfare of the partners. This review and documentation by counsel drafting general and limited partnership agreements are now of paramount significance. -

Trump V. Sierra Club, Et

No. 19A60 In the Supreme Court of the United States _______________________________ DONALD J. TRUMP, PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES, ET AL., Applicants, v. SIERRA CLUB, ET AL., Respondents, _______________________________ RESPONDENT’S OPPOSITION TO APPLICATION FOR STAY _______________________________ Sanjay Narayan Cecillia D. Wang Gloria D. Smith Counsel of Record SIERRA CLUB ENVIRONMENTAL AMERICAN CIVIL LIBERTIES LAW PROGRAM UNION FOUNDATION 2101 Webster Street, Suite 1300 39 Drumm Street Oakland, CA 94612 San Francisco, CA 94111 (415) 343-0770 Mollie M. Lee [email protected] Christine P. Sun AMERICAN CIVIL LIBERTIES Dror Ladin UNION FOUNDATION OF Noor Zafar NORTHERN CALIFORNIA, INC. Jonathan Hafetz 39 Drumm Street Hina Shamsi San Francisco, CA 94111 Omar C. Jadwat AMERICAN CIVIL LIBERTIES David Donatti UNION FOUNDATION Andre I. Segura 125 Broad Street AMERICAN CIVIL LIBERTIES New York, NY 10004 UNION FOUNDATION OF TEXAS P.O. Box 8306 David D. Cole Houston, TX 77288 AMERICAN CIVIL LIBERTIES UNION FOUNDATION 915 15th Street, NW Washington, D.C. 20005 Attorneys for Respondents CORPORATE DISCLOSURE STATEMENT In accordance with United States Supreme Court Rule 29.6, respondents make the following disclosures: 1) Respondents Sierra Club and Southern Border Communities Coalition do not have parent corporations. 2) No publicly held company owns ten percent or more of the stock of any respondent. 1 INTRODUCTION Defendants ask this Court, without full briefing and argument and despite their own significant delay, to allow them to circumvent Congress and immediately begin constructing a massive, $2.5 billion wall project through lands including Organ Pipe National Monument, Coronado National Memorial, the Cabeza Prieta National Wildlife Refuge, and the San Bernardino National Wildlife Refuge. -

9 Requirments of Due Diligence – Ezike

THE NIGERIANJURIDICALREVIEW Vol.13 (2015) Articles Pages Terrorism,ArmedConflictandtheNigerianChild:LegalFramework forChildRightsEnforcementinNigeria ~DamilolaS.Olawuyi 1 ClearingtheHurdles:ATherapeuticExaminationoftheChallengesto theProtectionandEnforcementofEconomic,SocialandCulturalRights ~DamianU.Ajah&IjeamakaNnaji 25 InequitableTradeRulesinWorldTradeOrganisation(WTO): ImpactonDevelopingCountries ~ EmekaAdibe&ObinneObiefuna 57 PublicParticipationinEnvironmentalImpactAssessmentinNigeria: ProspectsandProblems ~ HakeemIjaiya 83 RethinkingtheBasisofCorporateCriminalLiabilityinNigeria ~ CalistusN.Iyidiobi 103 ElevatingConsumerRightstoHumanRights ~FestusO.Ukwueze 131 WhenaTrademarkBecomesaVictimofItsOwnSuccess: TheIronyoftheConceptofGenericide ~NkemItanyi 157 EnvironmentalConstitutionalisminNigeria: AreWeThereYet? ~TheodoreOkonkwo 175 RequirementsofDueDiligenceonCapacityofNigerianGovernment Officials/Organs/AgentstoContract- GodwinAzubuikev.Government OfEnuguState inFocus ~ Rev.Fr.Prof.E.O.Ezike 217 FACULTYOFLAW UNIVERSITYOFNIGERIA,ENUGUCAMPUS EDITORIAL BOARD General Editor Dr. Edith O. Nwosu, LL.B., LL.M., Ph.D., B.L Assistant Editor Dr. Chukwunweike A. Ogbuabor, LL.B., LL.M., Ph.D., B.L Statute and Case Note Editor Professor Ifeoma P. Enemo, LL.B., LL.M., Ph.D., B.L Book Review Editor John F. Olorunfemi, LL.B., LL.M., B.L Distribution Coordinator Damian U. Ajah, LL.B., LL.M., B.L EDITORIAL ADVISORY BOARD Professor Boniface O. Okere, Professor Obiora Chinedu Okafor Docteur d’Universite de Paris LL.B (Nig), LL.M, (Nig) LL.M, Professor, -

Fiduciary Duty and Social Responsibility

Fiduciary Duty and Social Responsibility By Ben Branch and Jennifer Merton Dr. Branch is a Professor of Finance at the Isenberg School of Management at the University of Massachusetts-Amherst. He is an expert in bankruptcy investing, bankruptcy management, and valuing distressed assets. He has managed the estates for several large bankruptcies, including the bankruptcies of banks and other corporations and has been a director on several corporate boards. He is the author of several books on bankruptcy management and investing. He is widely published in professional journals. A member of the Academic Advisory Council of the Turnaround Management Association, he is the past President and past Trustee of the Eastern Finance Association. Jennifer Merton, Esq. is a Senior Lecturer in Law in the Management Department at the Isenberg School of Management at the University of Massachusetts-Amherst. She also serves as the Coordinator of the Law Faculty in the Management Department. Abstract: This paper focuses on the importance of the fiduciary duty that directors and officers of corporations owe to shareholders and explores the potential conflict between this duty and the desire of directors and officers to pursue corporate social responsibility policies. Fiduciary duty operates as an essential constraint on the behavior of directors and officers of corporations, providing protection for shareholders against decisions that are grossly incompetent or are tainted by a conflict of interest. Ethical decision-making cannot disregard the legal and ethical fiduciary duty owed to shareholders, even to promote socially responsible policies. However, this conflict can often be avoided because there is a strong business case for ethical behavior that promotes social and environmental goals, particularly when those goals align with various aspects of the business. -

Fiduciary Duties

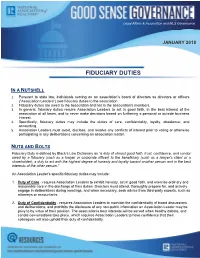

Legal Affairs & Association and MLS Governance JANUARY 2018 FIDUCIARY DUTIES IN A NUTSHELL 1. Pursuant to state law, individuals serving on an association’s board of directors as directors or officers (“Association Leaders”) owe fiduciary duties to the association. 2. Fiduciary duties are owed to the association and not to the association’s members. 3. In general, fiduciary duties require Association Leaders to act in good faith, in the best interest of the association at all times, and to never make decisions based on furthering a personal or outside business interest. 4. Specifically, fiduciary duties may include the duties of care, confidentiality, loyalty, obedience, and accounting. 5. Association Leaders must avoid, disclose, and resolve any conflicts of interest prior to voting or otherwise participating in any deliberations concerning an association matter. NUTS AND BOLTS Fiduciary Duty is defined by Black’s Law Dictionary as “a duty of utmost good faith, trust, confidence, and candor owed by a fiduciary (such as a lawyer or corporate officer) to the beneficiary (such as a lawyer’s client or a shareholder); a duty to act with the highest degree of honesty and loyalty toward another person and in the best interests of the other person.” An Association Leader’s specific fiduciary duties may include: 1. Duty of Care - requires Association Leaders to exhibit honesty, act in good faith, and exercise ordinary and reasonable care in the discharge of their duties. Directors must attend, thoroughly prepare for, and actively engage in deliberations during meetings, and when necessary, seek advice from third-party experts, such as attorneys or accountants. -

Rise and Fall of the Ultra Vires Doctrine in United States, United Kingdom, and Commonwealth Caribbean Corporate Common Law: a Triumph of Experience Over Logic

DePaul Business and Commercial Law Journal Volume 5 Issue 1 Fall 2006 Article 4 Rise and Fall of the Ultra Vires Doctrine in United States, United Kingdom, and Commonwealth Caribbean Corporate Common Law: A Triumph of Experience Over Logic Stephen J. Leacock Follow this and additional works at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/bclj Recommended Citation Stephen J. Leacock, Rise and Fall of the Ultra Vires Doctrine in United States, United Kingdom, and Commonwealth Caribbean Corporate Common Law: A Triumph of Experience Over Logic, 5 DePaul Bus. & Com. L.J. 67 (2006) Available at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/bclj/vol5/iss1/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Law at Via Sapientiae. It has been accepted for inclusion in DePaul Business and Commercial Law Journal by an authorized editor of Via Sapientiae. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Rise and Fall of the Ultra Vires Doctrine in United States, United Kingdom, and Commonwealth Caribbean Corporate Common Law: A Triumph of Experience Over Logic Stephen J.Leacock* "Pure logical thinking cannot yield us any knowledge of the empiri- cal world; all knowledge of reality starts from experience and ends in it."1 2 I. INTRODUCTION In free market3 economies, corporate laws change over time. More- over, experience has taught us that some legislative enactments, when * Professor of Law, Barry University School of Law. Barrister (Hons.) 1972, Middle Temple, London; LL.M. 1971, London University, King's College; M.A. (Bus. Law) CNAA 1971, City of London Polytechnic (now London Guildhall University), London; Grad. -

Discrimination As a Business Policy: the Misuse and Abuse of Corporate Social Responsibility Programs

American University Business Law Review Volume 8 Issue 3 Article 6 2020 Discrimination as a Business Policy: The Misuse and Abuse of Corporate Social Responsibility Programs Marc Greendorfer Tri Valley Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wcl.american.edu/aublr Part of the Business Organizations Law Commons Recommended Citation Greendorfer, Marc "Discrimination as a Business Policy: The Misuse and Abuse of Corporate Social Responsibility Programs," American University Business Law Review, Vol. 8, No. 3 (2020) . Available at: https://digitalcommons.wcl.american.edu/aublr/vol8/iss3/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Washington College of Law Journals & Law Reviews at Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in American University Business Law Review by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DISCRIMINATION AS A BUSINESS POLICY: THE MISUSE AND ABUSE OF CORPORATE SOCIAL RESPONSIBILITY PROGRAMS. MARC A. GREENDORFER* I. Introduction and Summary............................................................ 308 II. Theories of the Corporation ......................................................... 311 A. The Traditional Shareholder Primacy Norm and Duties of Corporate Directors ........................................................ 314 B. Stakeholder Theory ....................................................... -

The Duty of Loyalty in the Employment Relationship

Journal of Legal, Ethical and Regulatory Issues Volume 21, Issue 3, 2018 THE DUTY OF LOYALTY IN THE EMPLOYMENT RELATIONSHIP: LEGAL ANALYSIS AND RECOMMENDATIONS FOR EMPLOYERS AND WORKERS Frank J Cavico, Nova Southeastern University Bahaudin G Mujtaba, Nova Southeastern University Stephen Muffler, Nova Southeastern University ABSTRACT Capitalism, free markets and competition are all concepts and practices that are deemed to be good for the growth, development and sustainability of the economy while also benefiting consumers through more variety and lower prices. Of course, this assumption only holds true if markets and competition are open, honest and fair to all parties involved, including employers as every organization is entitled to faithful and fair service from its workers. The common law duty of loyalty in the employment relationship ensures fair competition and faithful service. Of course, a duty of loyalty is often violated when an employee begins to compete against his or her current employer. As such, the employee must not commit any illegal, disloyal, unethical or unfair acts toward his/her employer during the employment relationship. Accordingly, in this article, we provide a review of how the courts “draw the line” between permissible competition and disloyal actions. We discuss the key legal principles of the common law duty of loyalty, their implications for employees and employers and we provide practical recommendations for all parties in the employment relationship. Keywords: Duty of Loyalty, Faithless Servant, Fiduciary Relationships, Replevin, Common Law. INTRODUCTION This article examines the duty of loyalty in the employer-employee relationship. The focus is on the duty of the employee to act in a loyal manner while being employed by the employer. -

Modification of Fiduciary Duties in Limited Liability Companies

Modification of Fiduciary Duties in Limited Liability Companies James D. Johnson Jackson Kelly PLLC 221 N.W. Fifth Street P.O. Box 1507 Evansville, Indiana 47706-1507 812-422-9444 [email protected] James D. Johnson is a Member of Jackson Kelly PLLC resident in the Evansville, Indiana, office. He is Assistant Leader of the Commercial Law Practice Group and a member of the Construction Industry Group. For nearly three decades, Mr. Johnson has advised clients in a broad array of business matters, including complex commercial law, civil litigation and appellate law. He has been named to The Best Lawyers in America for Appellate Practice since 2007. Spencer W. Tanner of Jackson Kelly PLLC contributed to this manuscript. Modification of Fiduciary Duties in Limited Liability Companies Table of Contents I. Introduction ...................................................................................................................................................5 II. The Traditional Fiduciary Duties ..................................................................................................................5 III. Creation of Fiduciary Duties in Closely Held Business Organizations ......................................................6 A. General Partnerships ..............................................................................................................................6 B. Domestic Corporations ..........................................................................................................................6