First-Trimester Aspiration Abortion

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

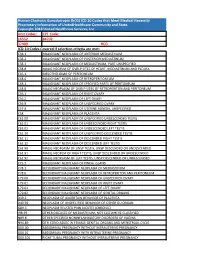

Human Chorionic Gonadotropin (Hcg) ICD 10 Codes That Meet Medical Necessity Proprietary Information of Unitedhealthcare Community and State

Human Chorionic Gonadotropin (hCG) ICD 10 Codes that Meet Medical Necessity Proprietary Information of UnitedHealthcare Community and State. Copyright 2018 United Healthcare Services, Inc Unit Codes: CPT Code: 16552 84702 37409 HCG ICD-10 Codes Covered if selection criteria are met: C38.1 MALIGNANT NEOPLASM OF ANTERIOR MEDIASTINUM C38.2 MALIGNANT NEOPLASM OF POSTERIOR MEDIASTINUM C38.3 MALIGNANT NEOPLASM OF MEDIASTINUM, PART UNSPECIFIED C38.8 MALIG NEOPLM OF OVRLP SITES OF HEART, MEDIASTINUM AND PLEURA C45.1 MESOTHELIOMA OF PERITONEUM C48.0 MALIGNANT NEOPLASM OF RETROPERITONEUM C48.1 MALIGNANT NEOPLASM OF SPECIFIED PARTS OF PERITONEUM C48.8 MALIG NEOPLASM OF OVRLP SITES OF RETROPERITON AND PERITONEUM C56.1 MALIGNANT NEOPLASM OF RIGHT OVARY C56.2 MALIGNANT NEOPLASM OF LEFT OVARY C56.9 MALIGNANT NEOPLASM OF UNSPECIFIED OVARY C57.4 MALIGNANT NEOPLASM OF UTERINE ADNEXA, UNSPECIFIED C58 MALIGNANT NEOPLASM OF PLACENTA C62.00 MALIGNANT NEOPLASM OF UNSPECIFIED UNDESCENDED TESTIS C62.01 MALIGNANT NEOPLASM OF UNDESCENDED RIGHT TESTIS C62.02 MALIGNANT NEOPLASM OF UNDESCENDED LEFT TESTIS C62.10 MALIGNANT NEOPLASM OF UNSPECIFIED DESCENDED TESTIS C62.11 MALIGNANT NEOPLASM OF DESCENDED RIGHT TESTIS C62.12 MALIGNANT NEOPLASM OF DESCENDED LEFT TESTIS C62.90 MALIG NEOPLASM OF UNSP TESTIS, UNSP DESCENDED OR UNDESCENDED C62.91 MALIG NEOPLM OF RIGHT TESTIS, UNSP DESCENDED OR UNDESCENDED C62.92 MALIG NEOPLASM OF LEFT TESTIS, UNSP DESCENDED OR UNDESCENDED C75.3 MALIGNANT NEOPLASM OF PINEAL GLAND C78.1 SECONDARY MALIGNANT NEOPLASM OF MEDIASTINUM C78.6 SECONDARY -

Hysteroscopy with Dilation and Curretage (D & C)

501 19th Street, Trustees Tower FORT SANDERS WOMEN’S SPECIALISTS 1924 Pinnacle Point Way Suite 401, Knoxville Tn 37916 P# 865-331-1122 F# 865-331-1976 Suite 200, Knoxville Tn 37922 Dr. Curtis Elam, M.D., FACOG, AIMIS, Dr. David Owen, M.D., FACOG, Dr. Brooke Foulk, M.D., FACOG Dr. Dean Turner M.D., FACOG, ASCCP, Dr. F. Robert McKeown III, M.D., FACOG, AIMIS, Dr. Steven Pierce M.D., Dr. G. Walton Smith, M.D., FACOG, Dr. Susan Robertson, M.D., FACOG HYSTEROSCOPY WITH DILATION AND CURRETAGE (D & C) Please read and sign the following consent form when you feel that you completely understand the surgical procedure that is to be performed and after you have asked all of your questions. If you have any further questions or concerns, please contact our office prior to your procedure so that we may clarify any pertinent issues. Definition: HysterosCopy is an outpatient procedure that allows your doctor direct visualization of the inside of the uterine cavity (womb) by inserting a thin lighted telescope (hysteroscope) through the vagina (birth canal) and cervix, without making an abdominal incision. This procedure enables your doctor to examine the lining of the uterus, look for polyps, fibroids, scar tissue, blockages of the fallopian tubes, and abnormal partitions. In addition, this procedure allows your doctor to remove or surgically treat many of the abnormalities seen. Dilation and Curettage (D&C) allows your doctor to take a sample of the tissue that lines your uterus (endometrium) and/or to remove polyps, fibroid tumors, or hyperplasia. Suction D&C is used in cases of miscarriage. -

HB 1429 Dismemberment Abortion SPONSOR(S): Grall and Others TIED BILLS: IDEN./SIM

HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES STAFF ANALYSIS BILL #: HB 1429 Dismemberment Abortion SPONSOR(S): Grall and others TIED BILLS: IDEN./SIM. BILLS: SB 1890 REFERENCE ACTION ANALYST STAFF DIRECTOR or BUDGET/POLICY CHIEF 1) Health Quality Subcommittee 9 Y, 6 N McElroy McElroy 2) Judiciary Committee 3) Health & Human Services Committee SUMMARY ANALYSIS Dilation and evacuation (D&E) abortions commonly involve the dismemberment of the fetus as part of the evacuation procedure. This dismemberment is performed on a living fetus unless the abortion provider has induced fetal demise prior to initiating the evacuation procedure. HB 1429 prohibits a physician from knowingly performing a dismemberment abortion. The bill defines a dismemberment abortion as: An abortion in which a person, with the purpose of causing the death of an fetus, dismembers the living fetus and extracts the fetus one piece at a time from the uterus through the use of clamps, grasping forceps, tongs, scissors, or a similar instrument that, through the convergence of two rigid levers, slices, crushes, or grasps, or performs any combination of those actions on, a piece of the fetus’ body to cut or rip the piece from the body. The bill provides an exception to this prohibition under certain circumstances if a dismemberment abortion is necessary to save the life of a mother and no other medical procedure would suffice for that purpose. Any person who knowingly performs or actively participates in a dismemberment abortion commits a third degree felony. The bill exempts a woman upon whom a dismemberment abortion has been performed from prosecution for a conspiracy to violate this provision. -

Mifepristone and Buccal Misoprostol Versus Mifepristone and Vaginal Misoprostol for Cervical Preparation in Second-Trimester Surgical Abortion

TITLE: A Randomized Double-blinded Comparison of 24-hour interval- Mifepristone and Buccal Misoprostol versus Mifepristone and Vaginal Misoprostol for Cervical Preparation in Second-Trimester Surgical Abortion PI: Frances Casey, MD, MPH NCT03134183 Unique Protocol ID: HM20005740 Document Approval Date: April 15, 2015 Document Type: Protocol and SAP A Randomized Double-blinded Comparison of 24-hour interval-Mifepristone and Buccal Misoprostol versus Mifepristone and Vaginal Misoprostol for Cervical Preparation in Second-Trimester Surgical Abortion Principal Investigator: Frances Casey, MD, MPH, Virginia Commonwealth University Medical Center Co-Investigators: Randi Falls, MD, Virginia League of Planned Parenthood 1. Abstract Patient preference for medications in place of osmotic dilators as cervical preparation is well known. Twenty-four to 48 hours following mifepristone, vaginal and buccal misoprostol have demonstrated equal efficacy in second-trimester medical abortion but have not been compared as cervical preparation for second-trimester surgical abortion. This study will randomize participants undergoing a second-trimester surgical abortion between 16 0/7-20 6/7 weeks gestation to 200mg mifepristone followed 20-24 hours later with 400mcg vaginal misoprostol and buccal placebo versus 400mcg buccal misoprostol and vaginal placebo 1-2 hours prior to the procedure. Primary outcome is intraoperative procedure time as measured by time of first instrument in the uterus (dilator if further dilation is required or forceps if no further dilation required) to last instrument out of the uterus. The study uses a superiority design and is powered to detect a 4-minute difference in procedure time from a baseline of 10±5 minutes with 90% power and two-tailed alpha of 0.05 requiring 33 participants in each arm. -

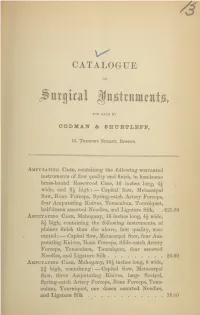

Catalogue of Surgical Instruments, for Sale by Codman & Shurtleff, 13

CATALOGUE OF jittigical KttjgtrttittitttjGi, FOR SALE BY CODMAI & SHUETLEPF, 13, Tremont Street, Boston. Amputating Case, containing the following warranted instruments of first quality and finish, in handsome brass-hound Rosewood Case, 16 inches long, 4\ wide, and high: — Capital Saw, Metacarpal Saw, Bone Forceps, Spring-catch Artery Forceps, four Amputating Knives, Tenaculum, Tourniquet, half-dozen assorted Needles, and Ligature Silk, . $25.00 Amputating Case, Mahogany, 16 inches long, 4\ wide, 8j high, containing the following instruments, of plainer finish than the above, first quality, war- ranted : — Capital Saw, Metacarpal Saw, four Am- putating Knives, Bone Forceps, Slide-catch Artery Forceps, Tenaculum, Tourniquet, four assorted Needles, and Ligature Silk 20.00 Amputating Case, Mahogany, inches long, 6 wide, 2f high, containing: — Capital Saw, Metacarpal Saw, three Amputating Knives, large Scalpel, Spring-catch Artery Forceps, Bone Forceps, Tena- culum, Tourniquet, one dozen assorted Needles, and Ligature Silk 18.50 2 CODMAN AND SHURTLEFF’S Amputating and Trepanning Case, Rosewood, brass bound, 16 inches long, wide, 3 high, containing the following instruments of first quality and finish, warranted:— Capital Saw, Metacarpal Saw, Bone Forceps, Spring-catch Artery Forceps, three Amputating Knives, large Scalpel, Tenaculum, Tourniquet, half-dozen assorted Needles, two Tre- phines, Hey’s Saw, Elevator, Brush, and Ligature Silk $35.00 Amputating and Trepanning Case (Parker’s Com- pact), Rosewood, brass bound, 12 inches long, 4 wide, 2J high, containing the following ivory- mounted instruments of best quality and finish, warranted:— Capital Saw, Metacarpal Saw, Hey’s Saw, three Amputating Knives adapted to one handle by screw, Finger Knife, Spring-catch Artery Forceps, Bone Forceps, Tenaculum, Tourniquet, Trephine, Elevator, Brush, six assorted Needles, and Ligature Silk 35.00 Amputating Cases fitted up to order, at prices corres- ponding with number and style of instruments. -

Model for Teaching Cervical Dilation and Uterine Curettage

Model for Teaching Cervical Dilation and Uterine Curettage Linda J. Gromko, MD, and Sam C. Eggertsen, MD Seattle, W a s h in g to n t least 15 percent of clinically recognizable pregnan METHODS A cies terminate in fetal loss, with the majority occur ring in the first trimester.1 Cervical dilation and uterine The fabric model was developed under the guidance of curettage (D&C) is frequently important in the manage physicians at the University of Washington Department ment of early pregnancy loss to control bleeding and re of Family Medicine and is commercially available.* The duce the risk of infection. D&Cs are also done for thera model, designed to approximate a 10-week last-menstrual- peutic first trimester abortions in family practice settings. period-sized uterus, is supported by elastic “ligaments” Resident experience may vary greatly, and some may feel on a wooden frame (Figure 1). A standard Graves spec inadequately trained in this procedure. The initial use of ulum can be inserted into the “vagina,” permitting vi gynecologic instruments (ie, tenaculum, sound, dilators, sualization of a cloth cervix. After placement of a tena curette) can feel awkward to the learner, and extensive culum onto the cervix, a paracervical block can be verbal tutoring may be discomfiting to the awake patient. demonstrated and the uterus sounded. Progressive dilation Training on a model can reduce these problems. After with Pratt or Denniston dilators follows: a drawstring al gaining basic skills on a model, the resident can focus on lows for the cervix to retain each successive degree of di gaining additional skills and refining technique during pa lation. -

Dilation and Evacuation (D & E)

FACT SHEET FOR PATIENTS AND FAMILIES Dilation and Evacuation (D & E) What is D & E ? Dilation (dy-LAY-shun] and evacuation [ee-vak-you-AY-shun] (D & E) is a procedure to open (dilate) the cervix and surgically clear the contents of the uterus (evacuation). It is typically done before 15 weeks of pregnancy or after a miscarriage. Because it signals the end of a pregnancy, the choice whether to have a D & E can be difficult. D& E is a common and safe procedure that usually takes about 20 minutes. What happens before D & E? You’ll have an appointment with your healthcare provider before your D & E. At this visit: • You will review the procedure and have a chance to ask questions. Bring a list of all prescriptions, over- the-counter medicines (such as allergy pills or cough Use this handout as a guide when talking with your healthcare provider. Be sure to ask any questions syrup), patches, vitamins, and herbs that you take. you may have so that you understand what will You may need to stop taking some of these a few days happen before, during, and after your D & E. before your procedure. • Your healthcare provider will prepare your cervix for the D & E. Common ways to open the cervix include If you’re having a D &E in a hospital the use of: Follow all instructions from your healthcare provider – Laminaria [lam-uh-NAIR-ee-uh] or Dilapan [DIL-uh-pan] about eating and drinking on the day before your dilators. These are thin sticks that are placed in procedure. -

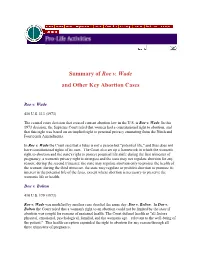

Summary of Roe V. Wade and Other Key Abortion Cases

Summary of Roe v. Wade and Other Key Abortion Cases Roe v. Wade 410 U.S. 113 (1973) The central court decision that created current abortion law in the U.S. is Roe v. Wade. In this 1973 decision, the Supreme Court ruled that women had a constitutional right to abortion, and that this right was based on an implied right to personal privacy emanating from the Ninth and Fourteenth Amendments. In Roe v. Wade the Court said that a fetus is not a person but "potential life," and thus does not have constitutional rights of its own. The Court also set up a framework in which the woman's right to abortion and the state's right to protect potential life shift: during the first trimester of pregnancy, a woman's privacy right is strongest and the state may not regulate abortion for any reason; during the second trimester, the state may regulate abortion only to protect the health of the woman; during the third trimester, the state may regulate or prohibit abortion to promote its interest in the potential life of the fetus, except where abortion is necessary to preserve the woman's life or health. Doe v. Bolton 410 U.S. 179 (1973) Roe v. Wade was modified by another case decided the same day: Doe v. Bolton. In Doe v. Bolton the Court ruled that a woman's right to an abortion could not be limited by the state if abortion was sought for reasons of maternal health. The Court defined health as "all factors – physical, emotional, psychological, familial, and the woman's age – relevant to the well-being of the patient." This health exception expanded the right to abortion for any reason through all three trimesters of pregnancy. -

Partial-Birth Abortion Ban Act SECTION 1

PUBLIC LAW 108–105—NOV. 5, 2003 117 STAT. 1201 Public Law 108–105 108th Congress An Act Nov. 5, 2003 To prohibit the procedure commonly known as partial-birth abortion. [S. 3] Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America in Congress assembled, Partial-Birth Abortion Ban Act SECTION 1. SHORT TITLE. of 2003. 18 USC 1531 This Act may be cited as the ‘‘Partial-Birth Abortion Ban Act note. of 2003’’. SEC. 2. FINDINGS. 18 USC 1531 note. The Congress finds and declares the following: (1) A moral, medical, and ethical consensus exists that the practice of performing a partial-birth abortion—an abortion in which a physician deliberately and intentionally vaginally delivers a living, unborn child’s body until either the entire baby’s head is outside the body of the mother, or any part of the baby’s trunk past the navel is outside the body of the mother and only the head remains inside the womb, for the purpose of performing an overt act (usually the puncturing of the back of the child’s skull and removing the baby’s brains) that the person knows will kill the partially delivered infant, performs this act, and then completes delivery of the dead infant—is a gruesome and inhumane procedure that is never medically necessary and should be prohibited. (2) Rather than being an abortion procedure that is embraced by the medical community, particularly among physi- cians who routinely perform other abortion procedures, partial- birth abortion remains a disfavored procedure that is not only unnecessary to preserve the health of the mother, but in fact poses serious risks to the long-term health of women and in some circumstances, their lives. -

Histomorphological Study of Chorionic Villi in Products of Conception Following First Trimester Abortions

November, 2018/ Vol 4/ Issue 7 Print ISSN: 2456-9887, Online ISSN: 2456-1487 Original Research Article Histomorphological study of chorionic villi in products of conception following first trimester abortions Shilpa MD1, Supreetha MS2, Varshashree3 1Dr. Shilpa, MD, Assistant Professor, 2Dr. Supreetha, MS, Assistant Professor, 3Dr. Varshashree, Post graduate, all authors are affiliated with Department of Pathology, Sri Devaraj Urs Medical College, Tamaka, Kolar, Karnataka, India. Corresponding Author: Dr. Shilpa, MD, Assistant Professor, Department of Pathology, Sri Devaraj Urs Medical College, Tamaka, Kolar, Karnataka, India. Email id: [email protected] ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………... Abstract Background: The common problem which occurs in first trimester of pregnancy is miscarriage. Retained products of conception are commonly received specimen for histopathological examination. Apart from confirmation of pregnancy, a careful examination can provide some additional information about the cause or the conditions associated with abortion. Aim: 1. To study various histopathological changes occurring in chorionic villi in first trimester spontaneous abortions and to know the pathogenesis of abortions. Materials and methods: This was a cross sectional retrospective study carried out for over a period of 3 years from January 2015 to January 2018. A total of 235biopsies were obtained from patient with the diagnosis of the first trimester spontaneous abortions were included in this study. Results: In our study most common age group of the abortion was between 21-30 years (63%). Incomplete abortion was the commonest type of abortion (47.7%). Many dysmorphic features were observed in this study like hydropic change (67%), stromal fibrosis (62%), villi with reduced blood vessels (52.7%) and perivillous fibrin deposition. -

Hysteroscopy an Internal Examination of Your Womb

We Care Doncaster and Bassetlaw Teaching Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust an internal examination Hysteroscopy of your womb This information leaflet has been given to you to help answer some of the questions you may have about having a hysteroscopy. It explains the benefits, risks and alternatives of the procedure as well as what you can expect when you come to hospital. If you have any questions or concerns, please do not hesitate to speak with your doctor or nurse. What is a hysteroscopy? A hysteroscopy is a procedure which uses a fine telescope, called a hysteroscope, to examine the lining and shape of the uterus (womb cavity). It is performed either in the outpatient department or in theatre, usually as a day patient. The Consultant will discuss with you where it is best for you to have the procedure. What are the benefits of having a hysteroscopy? A hysteroscopy can help to find the cause of problems relating to: • Heavy vaginal bleeding • Irregular periods • Bleeding between periods • Bleeding after sexual intercourse • Bleeding after menopause • Persistent discharge. In some cases, once a diagnosis has been made, the hysteroscope can also be used in the treatment of the problem. We Care WPR8773 Apr 2018 Review date by: Apr 2020 For example, problems that can be treated during a hysteroscopy are: • fibroids (growths in the uterus which are not cancer) • polyps (blood-filled growths which are not cancer) • thickening of the lining of the uterus (the endometrium) • removal of displaced intrauterine contraceptive devices removal of scar tissue. What are the risks associated with a hysteroscopy? Your Consultant/Doctor will explain these risks to you before you sign or give a verbal consent for the procedure. -

Risks of Hysteroscopy and Fractional Dilation and Curettage South Care Women's Florida

Risks of Hysteroscopy and Fractional Dilation and Curettage South Florida Women's Care The Procedure I will be undergoing is ______________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________________________________. 1. Damage to uterus, bowel, bladder, urinary organs: Perforation of the uterus is a small risk. If that were to occur, laparoscopy (placing a camera in the umbilicus) may need to be done to make sure the uterus wasn’t bleeding and repair any damage. Cervical stenosis (inability of the cervix to dilate) can increase the rise of uterine perforation. 2. Fluid overload: Special attention is taken to monitor exactly how much fluid goes into your uterus during the hysteroscopy. Rarely, extra fluid can accumulate in your lungs, called pulmonary edema. 3. Damage to nerves, skin: We are very careful to position your legs very gently before surgery. Rarely, the nerves in your legs can “go to sleep” during surgery and can have temporary nerve damage. 4. Infection: You are given an antibiotic during surgery to decrease any risk of infection. Rarely, infection can occur after surgery and need medicine, and even surgery to correct. 5. Need for further surgery: If your procedure involves treatment for heavy bleeding (i.e. Removing a polyp or endometrial ablation), it is possible that these procedures will not cure your underlying problem and further surgery will be needed. 6. Risks for endometrial ablation: Sometimes your cervix will not close over the device and cause the procedure to be abandoned for safety reasons. There is also risk of damage to abdominal organs. About 5-10% of ablations done need further surgery (hysterectomy) to stop heavy bleeding.