Model for Teaching Cervical Dilation and Uterine Curettage

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hysteroscopy with Dilation and Curretage (D & C)

501 19th Street, Trustees Tower FORT SANDERS WOMEN’S SPECIALISTS 1924 Pinnacle Point Way Suite 401, Knoxville Tn 37916 P# 865-331-1122 F# 865-331-1976 Suite 200, Knoxville Tn 37922 Dr. Curtis Elam, M.D., FACOG, AIMIS, Dr. David Owen, M.D., FACOG, Dr. Brooke Foulk, M.D., FACOG Dr. Dean Turner M.D., FACOG, ASCCP, Dr. F. Robert McKeown III, M.D., FACOG, AIMIS, Dr. Steven Pierce M.D., Dr. G. Walton Smith, M.D., FACOG, Dr. Susan Robertson, M.D., FACOG HYSTEROSCOPY WITH DILATION AND CURRETAGE (D & C) Please read and sign the following consent form when you feel that you completely understand the surgical procedure that is to be performed and after you have asked all of your questions. If you have any further questions or concerns, please contact our office prior to your procedure so that we may clarify any pertinent issues. Definition: HysterosCopy is an outpatient procedure that allows your doctor direct visualization of the inside of the uterine cavity (womb) by inserting a thin lighted telescope (hysteroscope) through the vagina (birth canal) and cervix, without making an abdominal incision. This procedure enables your doctor to examine the lining of the uterus, look for polyps, fibroids, scar tissue, blockages of the fallopian tubes, and abnormal partitions. In addition, this procedure allows your doctor to remove or surgically treat many of the abnormalities seen. Dilation and Curettage (D&C) allows your doctor to take a sample of the tissue that lines your uterus (endometrium) and/or to remove polyps, fibroid tumors, or hyperplasia. Suction D&C is used in cases of miscarriage. -

Do Nothing, Do Something, Aspirate: Management of Early Pregnancy

Disclosure Do Nothing, Do Something, • I train providers in Nexplanon insertion and removal Aspirate: • I do not receive any honoraria for this Management Of Early Pregnancy Loss Sarah Prager, MD, MAS Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology University of Washington Objectives Nomenclature By the end of this workshop participants will be able to: Early Pregnancy Loss/Failure (EPL/EPF) Spontaneous Abortion (SAb) 1. Understand diagnosis of early pregnancy loss (EPL) Miscarriage 2. Describe EPL management options in a clinic or the ED. 3. Describe the uterine evacuation procedure using These are all used interchangeably! the manual uterine aspirator (MUA). 4. Demonstrate the use of MUA for uterine Manual Uterine Aspiration/Aspirator (MUA) evacuation using papayas as simulation models. Manual Vacuum Aspiration/Aspirator (MVA) 5. Express an awareness of their own values related Uterine Evacuation to pregnancy and EPL management. Suction D&C/D&C/dilation and curettage Background Imperfect obstetrics: most don’t continue • Early Pregnancy Loss (EPL) is the most common complication of early pregnancy • 8–20% clinically recognized pregnancies • 13–26% all pregnancies • ~ 800,000 EPLs each year in the US • 80% of EPLs occur in 1st trimester • Many women with EPL first contact medical care through the emergency room Brown S, Miscarriage and its associations. Sem Repro Med. 1 Samantha Risk Factors for EPL • Age • 26 yo G2P1 presents to the • Prior SAb emergency room with vaginal • Smoking bleeding after a positive • Alcohol home pregnancy test. An • Caffeine (controversial) ultrasound shows a CRL of • Maternal BMI <18.5 or >25 7mm but no cardiac activity. • Celiac disease (untreated) • She wants to know why this • Cocaine happened. -

Dilation and Curettage (D&C) Consent Form

Dilation and Curettage (D&C) Consent Form Patient Name: ____________________________________________ Date of Birth: __________ Guardian Name (if applicable): ________________________________ Patient ID: ___________ Washington State law guarantees that you have both the right and the obligation to make decisions regarding your health care. Your physician can provide you with the necessary information and advice, but as a member of the health care team, you must participate in the decision making process. This form acknowledges your consent to treatment recommended by your physician. 1 MY PROCEDURE I hereby give my consent for Dr. or/and his/her associates to perform a Dilation and Curettage upon me. I understand the procedure is to be performed at the First Hill Surgery Center. This has been recommended to me by my physician in order to diagnose or treat dysfunctional uterine bleeding, menorrhagia (heavy menstrual bleeding) increased endometrial thickness, uterine polyps, and/or miscarriage. I understand that the procedure or treatment can be described as follows: The cervix is mechanically dilated and the lining of the uterus is either scraped or suctioned to remove tissue for possible biopsy. This procedure is routinely done in an outpatient surgery center and typically takes 15-20 minutes to complete. General anesthesia or sedation may be required for this procedure and will be administered by a qualified anesthesiologist. Your anesthesiologist will be available to discuss this further with you on the day of your procedure. 2 MY BENEFITS Some potential benefits of this procedure include: Removing tissue from the uterus may temporarily relieve abnormal bleeding lining; removing tissue for biopsy of the uterine lining; resolution of failed pregnancy. -

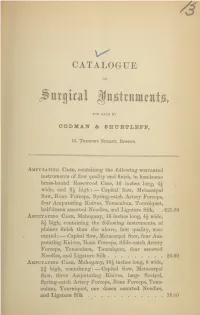

Catalogue of Surgical Instruments, for Sale by Codman & Shurtleff, 13

CATALOGUE OF jittigical KttjgtrttittitttjGi, FOR SALE BY CODMAI & SHUETLEPF, 13, Tremont Street, Boston. Amputating Case, containing the following warranted instruments of first quality and finish, in handsome brass-hound Rosewood Case, 16 inches long, 4\ wide, and high: — Capital Saw, Metacarpal Saw, Bone Forceps, Spring-catch Artery Forceps, four Amputating Knives, Tenaculum, Tourniquet, half-dozen assorted Needles, and Ligature Silk, . $25.00 Amputating Case, Mahogany, 16 inches long, 4\ wide, 8j high, containing the following instruments, of plainer finish than the above, first quality, war- ranted : — Capital Saw, Metacarpal Saw, four Am- putating Knives, Bone Forceps, Slide-catch Artery Forceps, Tenaculum, Tourniquet, four assorted Needles, and Ligature Silk 20.00 Amputating Case, Mahogany, inches long, 6 wide, 2f high, containing: — Capital Saw, Metacarpal Saw, three Amputating Knives, large Scalpel, Spring-catch Artery Forceps, Bone Forceps, Tena- culum, Tourniquet, one dozen assorted Needles, and Ligature Silk 18.50 2 CODMAN AND SHURTLEFF’S Amputating and Trepanning Case, Rosewood, brass bound, 16 inches long, wide, 3 high, containing the following instruments of first quality and finish, warranted:— Capital Saw, Metacarpal Saw, Bone Forceps, Spring-catch Artery Forceps, three Amputating Knives, large Scalpel, Tenaculum, Tourniquet, half-dozen assorted Needles, two Tre- phines, Hey’s Saw, Elevator, Brush, and Ligature Silk $35.00 Amputating and Trepanning Case (Parker’s Com- pact), Rosewood, brass bound, 12 inches long, 4 wide, 2J high, containing the following ivory- mounted instruments of best quality and finish, warranted:— Capital Saw, Metacarpal Saw, Hey’s Saw, three Amputating Knives adapted to one handle by screw, Finger Knife, Spring-catch Artery Forceps, Bone Forceps, Tenaculum, Tourniquet, Trephine, Elevator, Brush, six assorted Needles, and Ligature Silk 35.00 Amputating Cases fitted up to order, at prices corres- ponding with number and style of instruments. -

Dilation and Curettage (D&C)

Fact Sheet From ReproductiveFacts.org The Patient Education Website of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine Dilation and Curettage (D&C) This fact sheet was developed in collaboration with The Society of Reproductive Surgeons “Dilation and curettage” (D&C) is a short surgical as intestines, bladder, or blood vessels, are injured. If procedure that removes tissue from your uterus (womb). any of these organs are injured, they must be repaired You may need this procedure if you have unexplained with surgery. However, if no other organs have been or abnormal bleeding, or if you have delivered a baby injured, long-term complications from a perforation are and placental tissue remains in your womb. D&C also is extremely rare and the uterus heals on its own. performed to remove pregnancy tissue remaining from can occur after a D&C. If you are not a miscarriage or an abortion. Infections pregnant at the time of your D&C, this complication How is the procedure done? is extremely rare. However, 10% of women who were D&C can be done in a doctor’s office or in the hospital. pregnant before their D&C can get an infection, usually You may be given medications to relax you or to put you within 1 week of the procedure. It may be related to a to sleep for a short time. Your doctor will slowly widen sexually transmitted infection or due to normal bacteria the opening to your uterus (cervix). Opening your cervix that pass from the vagina into the uterus during or can cause cramping. -

Vantage by Integra® Miltex® Surgical Instruments

Vantage® by Integra® Miltex® Surgical Instruments Table of Contents Operating Scissors ................................................................................................................................. 4 Scissors ................................................................................................................................................ 5-6 Bandage Scissors .................................................................................................................................... 7 Dressing and Tissue Forceps ................................................................................................................. 8 Splinter Forceps ...................................................................................................................................... 9 Hemostatic Forceps......................................................................................................................... 10-12 of Contents Table Towel Clamps ......................................................................................................................................... 13 Tubing Forceps .......................................................................................................................................14 Sponge and Dressing Forceps ............................................................................................................. 15 Needle Holders .................................................................................................................................16-17 -

STILLE Surgical Instruments Kirurgisk Perfektion I Närmare 180 År Surgical Perfection for Almost 180 Years

STILLE Surgical Instruments Kirurgisk perfektion i närmare 180 år Surgical Perfection for almost 180 years I närmare 180 år har vi utvecklat och tillverkat de bästa kirurgiska For almost 180 years, we have developed and manufactured the best instrumenten till världens mest krävande kirurger. Vi vill rikta ett stort surgical instruments for the world’s most demanding surgeons. tack till alla våra trogna kunder och samtidigt välkomna våra nya kunder. We would like to extend a heartfelt thank you to all our loyal I den här katalogen presenterar vi vårt kompletta sortiment av customers and a warm welcome to our new customers. In this catalog STILLEs original instrument. we present our complete range of STILLE original surgical instruments. Precision, hållbarhet och känsla är typiska egenskaper för alla Precision, durability and feel are characteristic qualities of all STILLE STILLE-instrument. Den stora majoriteten är handgjorda av våra instruments. The vast majority are handcrafted by our highly skilled skickliga instrumentmakare Eskilstuna. Instrumentets resa från rundstål instrument makers in Eskilstuna, west of Stockholm, Sweden. The instru- till ett färdigt instrument är lång, och består av många tillverkningssteg. ments’ journey from a rod of stainless steel to a finished instrument is a STILLEs unika tillverkningsmetod och användning av enbart det bästa long one, involving multiple stages. STILLE’s unique method of crafting its materialet ger våra instrument deras unika känsla och hållbarhet. instrument materials, and its usage of only the very highest-grade steels, give our instruments their unique feel and durability. I det första kapitlet hittar du våra saxar, allt från vanliga operationssaxar till våra unika SuperCut och Diamond SuperCut-saxar. -

The Political and Moral Battle Over Late-Term Abortion

CROSSING THE LINE: THE POLITICAL AND MORAL BATTLE OVER LATE-TERM ABORTION Rigel C. Oliverit "This is an emotional,distorted debate. We are using the lives ofa few women to create divisions across this country... -Senator Patty Murray' I. INTRODUCTION The 25 years following the Supreme Court's landmark decision in Roe v. Wade2 have seen a tremendous amount of social and political activism on both sides of the abortion controversy. Far from settling the issue of a woman's constitutional right to an abortion, the Roe decision galvanized pro-life and pro- choice groups and precipitated many small "battles" in what many on both sides view to be a "war" between fetal protection and women's access to reproductive choice. These battles have occurred at the judicial, grassroots, and political levels, with each side gaining and losing ground. Pro-life activists staged a nation-wide campaign of clinic protests, which led to Congress's 1994 enactment of the Federal Access to Clinic Entrances law creating specific civil and criminal penalties for violence outside of abortion clinics.3 State legislatures imposed limitations on the right to abortion, including mandatory waiting periods and requirements for parental or spousal notification. Many of these limitations were then challenged before the Supreme Court, which struck down or upheld them according to the "undue burden" standard of review articulated in PlannedParenthood of Southeastern Pennsylvania v. Casey.4 Recent developments have shifted the focus of conflict from clinic entrances and state regulation of abortion access to the abortion procedures themselves. The most controversial procedures include RU-486--the "abortion drug"-and a particular late term surgical procedure called intact dilation and extraction ("D&X")-more popularly known as "partial-birth abortion." The controversy surrounding the D&X procedure escalated dramatically in June of 1995, when both houses of Congress first introduced legislation to ban the procedure. -

2019 Charge Schedules 12.20.2018.Xlsx

DESCRIPTION 2019 Charge HCHG =E GRADIENT STRIP 39.70 HCHG 10 ML ABLAVAR PER ML 37.10 HCHG 10 ML EOVIST PER ML 39.80 HCHG 11 - DEOXYCORTISOL 135.30 HCHG 14 3 3 PROTEIN CSF 347.00 HCHG 15 ML ABLAVAR PER ML 37.10 HCHG 17 OH PREGNENOLONE 87.70 HCHG 17/OH PROGESTERONE 66.20 HCHG 21 HYDROXYLASE ANTIBODY 297.30 HCHG 2TS AFP 139.60 HCHG 2TS ESTRIOL 197.80 HCHG 2TS HCG 95.20 HCHG 2TS INHIBIN A 130.00 HCHG 3D SENSOR VEST PR4270 12,818.00 HCHG 5HIAA QUANT 99.50 HCHG A1A PHENOTYPE 82.40 HCHG ABD PILLOW PR20 75.00 HCHG ABD RETRACTION SYSTEM 98.20 HCHG ABDOMINAL DOPPLER LTD STUDY 453.40 HCHG ABO GROUP 36.30 HCHG ABY SCREEN 97.90 HCHG ACCESS VENOUS ADVANCED 280.90 HCHG ACETAMINOPHEN 153.80 HCHG ACETYLCHOLINE RECEP BIND 180.00 HCHG ACETYLCHOLINE RECEPTOR MOD ABY 247.50 HCHG ACETYLCHOLINESTERASE RBC 147.70 HCHG ACHR GANGLIONIC NEURONAL ABY SERUM 264.00 HCHG ACT. PROTEIN C RESIST 158.60 HCHG ACTH 53.50 HCHG ACTH STIMULATION PANEL 182.00 HCHG ACTIVATED PTT 55.00 HCHG ACTIVE CORD 298.10 HCHG ACUTE HEPATITIS PANEL 239.50 HCHG ACYLCARNITINES QUANT PLASMA 150.50 HCHG ACYLGLYCINES,QUANT,URINE 484.80 HCHG ADAPTOR/EXT PACING/NEUROSTIMULATOR LEAD PR527 1,663.50 HCHG ADDL DISC SUSCEPT 58.00 HCHG ADENOVIRUS IGG 267.10 HCHG ADENOVIRUS PCR 245.70 HCHG ADHESION BARRIER PR250 787.50 HCHG ADHESION BARRIER PR275 862.50 HCHG ADHESION BARRIER PR300 945.00 HCHG ADHESION BARRIER PR330 1,038.00 HCHG ADMIN OF PNEUMOCOCCAL VACCINE 16.30 HCHG ADMIN OF SEASONAL INFLUENZA VACCINE 16.30 HCHG ADMIN SET PEDS FILTER & SYRINGE 29.30 HCHG ADMIN SET-PLTS & CRYO 291.20 HCHG ADMINISTRATION -

CRS Report for Congress Received Through the CRS Web

95-1101 SPR Updated November 17, 1997 CRS Report for Congress Received through the CRS Web Abortion Procedures Irene E. Stith-Coleman Specialist in Life Sciences Science Policy Research Division Summary The Partial-Birth Abortion Ban Act of 1997, H.R. 1122 was vetoed by President Clinton on October 10, 1997. This legislation would have made it a federal crime, punishable by fine and/or incarceration, for a physician to perform a partial birth abortion unless it was necessary to save the life of a mother whose life is endangered by a physical disorder, illness, or injury. The bill permitted a defendant to seek a hearing before the State Medical Board on whether the physician’s conduct was necessary to save the life of the mother. H.R.1122 defined a partial birth abortion as “an abortion in which the person performing the abortion partially vaginally delivers a living fetus before killing the fetus and completing the delivery.” In his veto message to Congress, the President indicated that he vetoed H.R. 1122 for “exactly the same reasons” he vetoed similar legislation, H.R.1833, in April 1996. With that 1996 veto, the President asserted that if Congress presented him with a bill amended to add an exception for partial birth abortions for “serious health consequences,” to the mother, he would sign it. Congress did not attempt to override the veto of H.R.1122 before it adjourned, but do intend to try to override it in the second session. The partial-birth abortion legislation has stimulated a great deal of controversy. -

Unintended Pregnancy and Induced Abortion in the Philippines

Unintended Pregnancy And Induced Abortion In the Philippines CAUSES AND CONSEQUENCES Unintended Pregnancy And Induced Abortion In the Philippines: Causes and Consequences Susheela Singh Fatima Juarez Josefina Cabigon Haley Ball Rubina Hussain Jennifer Nadeau Acknowledgments Unintended Pregnancy and Induced Abortion in the Philippines; Alfredo Tadiar (retired), College of Law and Philippines: Causes and Consequences was written by College of Medicine, University of the Philippines; and Susheela Singh, Haley Ball, Rubina Hussain and Jennifer Cecille Tomas, College of Medicine, University of the Nadeau, all of the Guttmacher Institute; Fatima Juarez, Philippines. Centre for Demographic, Urban and Environmental The contributions of a stakeholders’ forum were essential Studies, El Colegio de México, and independent consult- to determining the scope and direction of the report. The ant; and Josefina Cabigon, University of the Philippines following participants offered their input and advice: Population Institute. The report was edited by Susan Merlita Awit, Women’s Health Care Foundation; Hope London, independent consultant. Kathleen Randall, of the Basiao-Abella, WomenLead Foundation; Ellen Bautista, Guttmacher Institute, supervised production of the report. EngenderHealth; Kalayaan Pulido Constantino, PLCPD; The authors thank the following current and former Jonathan A. Flavier, Cooperative Movement for Guttmacher Institute staff members for providing assis- Encouraging NSV (CMEN); Gladys Malayang, Health and tance at various stages of the report’s preparation: Development Institute; Alexandrina Marcelo, Reproductive Akinrinola Bankole, Erin Carbone, Melanie Croce-Galis, Rights Resource Group (3RG); Junice Melgar, Linangan ng Patricia Donovan, Dore Hollander, Sandhya Ramashwar Kababaihan (Likhaan); Sharon Anne B. Pangilinan, and Jennifer Swedish. The authors also acknowledge the Institute for Social Science and Action; Glenn Paraso, contributions of the following colleagues at the University Philippine Rural Reconstruction Movement; Corazon M. -

Miscarriage and the Dignity of the Human Body

Hope for Healing: Miscarriage and the Dignity of the Human Body Andrew J. Sodergren, M.S. Abstract This paper examines the issue of miscarriage from the perspective of the mother-child couplet. A discussion of the psychology of motherhood and miscarriage highlights the negative impact miscarriage has on the mother. Mothers must be helped to mourn the irreplaceable child lost in miscarriage. A review of Catholic teaching on the human body and dignity of the unborn emphasizes the respect owed to pre-natal human life and the bodies of embryos and fetuses who have died. Finally, it is argued that holding a funeral/burial is the best possible way to assist the mother’s grieving and to respect the deceased child. Current practices and attitudes fail to recognize either of these norms. Hope for Healing: Miscarriage and the Dignity of the Human Body Catholic bioethicists today are continually confronted with a number of pressing issues raised by the culture of death and new medical technologies: stem cell research, cloning, frozen embryos, reproductive technologies, euthanasia, and the like. While it is necessary that scholars and Church officials devote their energies to responding to these many new challenges, a regrettable consequence of this is that less controverted, more mundane issues are sometimes overlooked. When this happens, people are left without sound ethical guidance and support for dealing with situations in their lives. This is precisely the case with miscarriage, a very common and morally delicate event that has received little attention. Central to the issue of miscarriage is the care due to the two people most affected by it: the mother and her unborn child.