The Triad an Interconnected Web

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

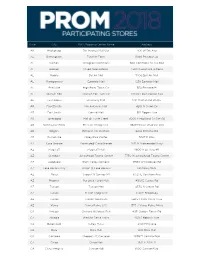

Prom 2018 Event Store List 1.17.18

State City Mall/Shopping Center Name Address AK Anchorage 5th Avenue Mall-Sur 406 W 5th Ave AL Birmingham Tutwiler Farm 5060 Pinnacle Sq AL Dothan Wiregrass Commons 900 Commons Dr Ste 900 AL Hoover Riverchase Galleria 2300 Riverchase Galleria AL Mobile Bel Air Mall 3400 Bell Air Mall AL Montgomery Eastdale Mall 1236 Eastdale Mall AL Prattville High Point Town Ctr 550 Pinnacle Pl AL Spanish Fort Spanish Fort Twn Ctr 22500 Town Center Ave AL Tuscaloosa University Mall 1701 Macfarland Blvd E AR Fayetteville Nw Arkansas Mall 4201 N Shiloh Dr AR Fort Smith Central Mall 5111 Rogers Ave AR Jonesboro Mall @ Turtle Creek 3000 E Highland Dr Ste 516 AR North Little Rock Mc Cain Shopg Cntr 3929 Mccain Blvd Ste 500 AR Rogers Pinnacle Hlls Promde 2202 Bellview Rd AR Russellville Valley Park Center 3057 E Main AZ Casa Grande Promnde@ Casa Grande 1041 N Promenade Pkwy AZ Flagstaff Flagstaff Mall 4600 N Us Hwy 89 AZ Glendale Arrowhead Towne Center 7750 W Arrowhead Towne Center AZ Goodyear Palm Valley Cornerst 13333 W Mcdowell Rd AZ Lake Havasu City Shops @ Lake Havasu 5651 Hwy 95 N AZ Mesa Superst'N Springs Ml 6525 E Southern Ave AZ Phoenix Paradise Valley Mall 4510 E Cactus Rd AZ Tucson Tucson Mall 4530 N Oracle Rd AZ Tucson El Con Shpg Cntr 3501 E Broadway AZ Tucson Tucson Spectrum 5265 S Calle Santa Cruz AZ Yuma Yuma Palms S/C 1375 S Yuma Palms Pkwy CA Antioch Orchard @Slatten Rch 4951 Slatten Ranch Rd CA Arcadia Westfld Santa Anita 400 S Baldwin Ave CA Bakersfield Valley Plaza 2501 Ming Ave CA Brea Brea Mall 400 Brea Mall CA Carlsbad Shoppes At Carlsbad -

APG Advisors the News Wrap-Up 09.02.20

APG Advisors The News Wrap-Up 09.02.20 California investor spends $590 million to expand footprint in Research Triangle Park. California-based Alexandria Real Estate Equities Inc. closed on 253 acres at Parmer RTP for $590.4 million. The purchase includes seven parcels across three deed transfers with properties at 14 TW Alexander Drive, 5 Moore Drive, 41 Moore Drive, two at 1818 Ellis Road, and two at 2400 Ellis Road. The seller, Los Angeles-based Karlin Real Estate, has been assembling land and developing the 500-acre Parmer RTP campus for years. Among the largest assemblages in Research Triangle Park, Parmer RTP is an R&D campus of 20 buildings, with tenants such as LabCorp and Credit Suisse. Source: Triangle Business Journal WeWork will leave Durham.ID. Coworking giant WeWork plans to close its location in Durham ID at the end of the year, vacating three floors of office space. The decision to leave Durham.ID is not in response to the pandemic. The review had been in the works since last fall. “As part of WeWork’s plan to seek profitable growth and optimize our global real estate portfolio, we have worked with our landlord partners to consolidate to a single Durham flagship location at One City Center,” said WeWork Vice President Dave McLaughlin. The closure clears the way for new owner Longfellow Real Estate Partners, which paid $138 million last month for full ownership of Durham ID, including Buildings A at 200 Morris and B at 300 Morris St. According to the seller, Bain Capital, “Longfellow was interested in purchasing the project from the partnership but had a business plan that was predicated upon access to WeWork’s space. -

Leaf and Brush Quadrants

Leaf and Brush Quadrants WE ATHE REND NB 52_B ETHA NIA RURA L HALL RD BURNSIDE KILS TROM SHORE MONTROYA L PINNA CLE BE THANIA RURAL HA LL RD_S B 52 WHISPERWOOD LO NGS HADOW SCOFIELD TO FIND YOUR QUADRANT: SK YEBUCKHAV EN AB BE Y AURORAGLEN JA MMIE PRES TWICK BA LMORAL HILL MIZ PAH CHURCH BANNOCKBURN MARTHA L HWY 66_NB 52 FLORENCE A T S V E SB 5 2_ VILLAGE OAK H HWY 66 WY 66 HWYUNIVE 66 RSIT Y S TAN L CRE STLA WNFERNTREE EYVIL A NOR FERNCRESLO NG CREE K T L E M SHUMATE VIRGINIA LAK E 1) Type your street name in the FIND box above the map FINWICK NY LON MATTHE WS LANDON THORNWOOD SUMM ER T RACE BE AVE R POND TONYA TURF WOOD HUCKLEBERRY NORM AN AMB ERWOOD SHERRI LYNN CHE SRIDGE WILLOWDALE BRAK ENWOOD ZIGLA R AVE RLA N BUSHB ERRY BUNNY GYDDIE RIVE R DALE MOS SGRE EN PHELP S BE THANIA-RURAIE L HALL MARTY BLUE RIDGE EA GLE CRE ST K HUNTING TON RIDGE GRAINWOOD B C ET HA I ALMA NIA -T TEETIME PHELP S OBA V STANLE YV ILLE K C KOGE R (For example: Enter only the name "MILLER" and CLIFFS IDE TOHARI C KE IL FA IRCRES T NITA OLD HOLLOW O BE LLE BE THANIAL PLACE O HARVE ST STO NE FOX CHAS E L CANNO Y I O B KILBV Y FAWN FORES T R R I W L BE THANIA OA KS A AUTUMN B L M NOE L LE WEY R T E B MEA DOW SWE ETB RIAR LE WBRIGHT LEA F O S ROCK S PRING O HARPWE LL BROWNWOOD O E RENWOOD P O WHITEOA K R D P N I LO RE N ECHO HARRINGTON VILLAGE C ANGEL OAK S H STAGE COACH O STONE WA Y LO DGE CRES T K I W ROLLING GREEN O NB 52 LESLIE T CORA L A NOT "MILLER STREET") POLA RIS O HANES M ILL RD_NB 52 MERRY DALE L R PE NNE R RE FLE CT ION T L MURRAY SB 52_W HA NES MILL -

Download Flyer

GREYSTONE PROFESSIONAL CENTER 2025 FRONTIS PLAZA | WINSTON-SALEM REED GRIFFITH Executive VP, Leasing & Brokerage d. 704-971-8908 [email protected] 3340 Silas Creek Parkway d R n i d a t d R R n e u ll n vi o o s t M id n e a x R u m r a R e e B yn G ol da R GREYSTONE PROFESSIONALd CENTER | 2025 FRONTISWalkertow nPLAZA BLVD. | WINSTON SALEM P a t t e r s o n A v d e R N e l E il in v adk Y Oak Crest 311 tain St oun PROPERTYM SUMMARY Forsyth W Greystone Professional Center is a 4-story Class “A” building located just off of y w North Winston k Kernersville P k Hanes Mall Boulevard, near Novant Health’s Forsyth Medical Center. Ample e 421 e r C s parking, abundant nearby amenities, ease of accessibility, signage opportunity, a l i Winston-Salem Rd Lewisville S ille sv 421 er and proximity to numerous medical practices combine to make this property rn Ke desirable for 4a0 variety of tenants. Co-tenants include: Digestive Health Harmony Grove d Specialists,R and Novant Health practices - Summit Sleep & Neurology, The Breast d St s R n s W w o d aughto r r Sunnyside o C f Center, and Imaging. t n a t r o i t Hootstown S S n n S i T U a h Hi Jonestown M o gh m P S oi as nt R vi d lle Rd Swaimtown LOCATION Clemmons NC H igh Greystone Professional Center is conveniently located just off Hanes Mall way 801 N Wallburg Bermuda Run Boulevard, adjacent to Novant Health’s corporate headquarters building in Rd ee tr m Gu Winston Salem, North Carolina. -

Store # State City Mall/Shopping Center Name Address Date 2918

Store # State City Mall/Shopping Center Name Address Date 2918 AL ALABASTER COLONIAL PROMENADE 340 S COLONIAL DR Coming Soon in September 2016! 2218 AL HOOVER RIVERCHASE GALLERIA 2300 RIVERCHASE GALLERIA Coming Soon in September 2016! 2131 AL HUNTSVILLE MADISON SQUARE 5901 UNIVERSITY DR Coming Soon in September 2016! 219 AL MOBILE BEL AIR MALL MOBILE, AL 36606-3411 Coming Soon in September 2016! 2840 AL MONTGOMERY EASTDALE MALL MONTGOMERY, AL 36117-2154 Coming Soon in September 2016! 2956 AL PRATTVILLE HIGH POINT TOWN CENTER PRATTVILLE, AL 36066-6542 Coming Soon in September 2016! 2875 AL SPANISH FORT SPANISH FORT TOWN CENTER 22500 TOWN CENTER AVE Coming Soon in September 2016! 2869 AL TRUSSVILLE TUTWILER FARM 5060 PINNACLE SQ Coming Soon in September 2016! 2709 AR FAYETTEVILLE NW ARKANSAS MALL 4201 N SHILOH DR Coming Soon in September 2016! 1961 AR FORT SMITH CENTRAL MALL 5111 ROGERS AVE Coming Soon in September 2016! 2914 AR LITTLE ROCK SHACKLEFORD CROSSING 2600 S SHACKLEFORD RD Coming Soon in July 2016! 663 AR NORTH LITTLE ROCK MC CAIN SHOPPING CENTER 3929 MCCAIN BLVD STE 500 Coming Soon in July 2016! 2879 AR ROGERS PINNACLE HLLS PROMDE 2202 BELLVIEW RD Coming Soon in September 2016! 2936 AZ CASA GRANDE PROMNDE AT CASA GRANDE 1041 N PROMENADE PKWY Coming Soon in September 2016! 157 AZ CHANDLER MILL CROSSING 2180 S GILBERT RD Coming Soon in September 2016! 251 AZ GLENDALE ARROWHEAD TOWNE CENTER 7750 W ARROWHEAD TOWNE CENTER Coming Soon in September 2016! 2842 AZ GOODYEAR PALM VALLEY CORNERST 13333 W MCDOWELL RD Coming Soon in September -

CBL & Associates Properties 2012 Annual Report

COVER PROPERTIES : Left to Right/Top to Bottom MALL DEL NORTE, LAREDO, TX CROSS CREEK MALL, FAYETTEVILLE, NC BURNSVILLE CENTER, BURNSVILLE, MN OAK PARK MALL, KANSAS CITY, KS CBL & Associates Properties, Inc. 2012 Annual When investors, business partners, retailers Report CBL & ASSOCIATES PROPERTIES, INC. and shoppers think of CBL they think of the leading owner of market-dominant malls in CORPORATE OFFICE BOSTON REGIONAL OFFICE DALLAS REGIONAL OFFICE ST. LOUIS REGIONAL OFFICE the U.S. In 2012, CBL once again demon- CBL CENTER WATERMILL CENTER ATRIUM AT OFFICE CENTER 1200 CHESTERFIELD MALL THINK SUITE 500 SUITE 395 SUITE 750 CHESTERFIELD, MO 63017-4841 strated why it is thought of among the best 2030 HAMILTON PLACE BLVD. 800 SOUTH STREET 1320 GREENWAY DRIVE (636) 536-0581 THINK 2012 Annual Report CHATTANOOGA, TN 37421-6000 WALTHAM, MA 02453-1457 IRVING, TX 75038-2503 CBLCBL & &Associates Associates Properties Properties, 2012 Inc. Annual Report companies in the shopping center industry. (423) 855-0001 (781) 398-7100 (214) 596-1195 CBLPROPERTIES.COM HAMILTON PLACE, CHATTANOOGA, TN: Our strategy of owning the The 2012 CBL & Associates Properties, Inc. Annual Report saved the following resources by printing on paper containing dominant mall in SFI-00616 10% postconsumer recycled content. its market helps attract in-demand new retailers. At trees waste water energy solid waste greenhouse gases waterborne waste Hamilton Place 5 1,930 3,217,760 214 420 13 Mall, Chattanooga fully grown gallons million BTUs pounds pounds pounds shoppers enjoy the market’s only Forever 21. COVER PROPERTIES : Left to Right/Top to Bottom MALL DEL NORTE, LAREDO, TX CROSS CREEK MALL, FAYETTEVILLE, NC BURNSVILLE CENTER, BURNSVILLE, MN OAK PARK MALL, KANSAS CITY, KS CBL & Associates Properties, Inc. -

Opticianry Employers - USA

www.Jobcorpsbook.org - Opticianry Employers - USA Company Business Street City State Zip Phone Fax Web Page Anchorage Opticians 600 E Northern Lights Boulevard, # 175 Anchorage AK 99503 (907) 277-8431 (907) 277-8724 LensCrafters - Anchorage Fifth Avenue Mall 320 West Fifth Avenue Ste, #174 Anchorage AK 99501 (907) 272-1102 (907) 272-1104 LensCrafters - Dimond Center 800 East Dimond Boulevard, #3-138 Anchorage AK 99515 (907) 344-5366 (907) 344-6607 http://www.lenscrafters.com LensCrafters - Sears Mall 600 E Northern Lights Boulevard Anchorage AK 99503 (907) 258-6920 (907) 278-7325 http://www.lenscrafters.com Sears Optical - Sears Mall 700 E Northern Lght Anchorage AK 99503 (907) 272-1622 Vista Optical Centers 12001 Business Boulevard Eagle River AK 99577 (907) 694-4743 Sears Optical - Fairbanks (Airport Way) 3115 Airportway Fairbanks AK 99709 (907) 474-4480 http://www.searsoptical.com Wal-Mart Vision Center 537 Johansen Expressway Fairbanks AK 99701 (907) 451-9938 Optical Shoppe 1501 E Parks Hy Wasilla AK 99654 (907) 357-1455 Sears Optical - Wasilla 1000 Seward Meridian Wasilla AK 99654 (907) 357-7620 Wal-Mart Vision Center 2643 Highway 280 West Alexander City AL 35010 (256) 234-3962 Wal-Mart Vision Center 973 Gilbert Ferry Road Southeast Attalla AL 35954 (256) 538-7902 Beckum Opticians 1805 Lakeside Circle Auburn AL 36830 (334) 466-0453 Wal-Mart Vision Center 750 Academy Drive Bessemer AL 35022 (205) 424-5810 Jim Clay Optician 1705 10th Avenue South Birmingham AL 35205 (205) 933-8615 John Sasser Opticians 1009 Montgomery Highway, # 101 -

2018 Community Health Assessment

Table of Contents ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS V EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1 CHAPTER 1 BACKGROUND AND INTRODUCTION 3 CHAPTER 2 BRIEF COUNTY DESCRIPTION 4 Demographics 5 Population 5 CHAPTER 3 COMMUNITY ASSESSMENT PROCESS 8 Methodology 8 Description of Community Based Participatory Research and Focus Group Findings 10 Alamance County Community Forum Findings 11 CHAPTER 4 COMMUNITY PRIORITIES AND ACCOMPLISHMENTS 12 Access to Care 12 Access to Health Care 19 Education 23 Economy 28 CHAPTER 5 RACIAL AND ETHNIC DISPARITIES 34 CHAPTER 6 HEALTH AND WELL-BEING 37 Mortality 37 Morbidity 39 Cancer 40 Heart Disease and Stroke 41 Diabetes 41 Infectious Diseases 43 ii Communicable Diseases: Sexually Transmitted Infections 45 Data on the Burden of STIs and HIV 46 Obesity 51 Oral Health 52 Lead Poisoning 53 Mental Health 54 Prenatal, Infant, and Maternal Health 57 Reproductive Health and Life 60 Substance Abuse and Prevention Programs 64 DETERMINANTS OF HEALTH 66 Healthy Days and Disability 67 Families 68 Crime/Intentional Injuries 69 Social Support/Civic Engagement 69 Religion 70 Financial and Economic Factors 70 Financial Assistance 71 Transportation 72 Individual Behavior 74 Income Inequality 74 Housing 78 Food Security 80 Motor Vehicles 81 Land Use 82 Pollution and Air Quality 84 Water Quality 84 iii Parks and Recreation 85 COUNTY DATA BOOK 86 APPENDIX A 87 Acknowledgements 87 APPENDIX B 90 Additional Data & Information 90 APPENDIX C 117 Citations & Resources 117 iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This assessment would not be possible without the assistance and support of many individuals and groups who live and work in Alamance County. The strategies developed from this assessment will be a direct response to the needs identified by the residents of Alamance County – A sincere thank you to all residents for your willingness to share your opinions and experiences related to living in Alamance County. -

Total Mall Store GLA(2)

Mall Store Year of Sales Percentage Year of Most Total per Mall Opening/ Recent Our Total Mall Store Square Store GLA Anchors & Junior Mall / Location Acquisition Expansion Ownership GLA (1) GLA(2) Foot (3) Leased (4) Anchors (5) Post Oak Mall 1982 1985 100% 774,922 287,397 374 92 % Beall's, Dillard's Men & College Station, TX Home, Dillard's Women & Children, Encore, JC Penney, Macy's, Sears Richland Mall 1980/2002 1996 100% 685,730 204,505 355 95 % Beall's, Dillard's for Waco, TX Men, Kids & Home, Dillard's for Women, JC Penney, Sears, XXI Forever South County Center 1963/2007 2001 100% 1,044,247 311,381 352 92 % Dick's Sporting Goods, St. Louis, MO Dillard's, JC Penney, Macy's, Sears Southpark Mall 1989/2003 2007 100% 672,902 229,642 346 95 % Dick's Sporting Goods, Colonial Heights, VA JC Penney, Macy's, Regal Cinema, Sears Turtle Creek Mall 1994 1995 100% 845,946 192,559 320 98 % Belk, Dillard's, Garden Hattiesburg, MS Ridge, JC Penney, Sears, Stein Mart, United Artist Theater Valley View Mall 1985/2003 2007 100% 844,193 285,175 342 100 % Barnes & Noble, Belk, Roanoke, VA JC Penney, Macy's, Macy's for Home & Children, Sears Westmoreland Mall 1977/2002 1994 100% 999,641 303,802 323 96 % Bon-Ton, JC Penney, Greensburg, PA Macy's, Macy's Home Store, Old Navy, Sears, former Steve & Barry's York Galleria 1989/1999 N/A 100% 764,710 227,493 343 94 % Bon-Ton, Boscov's, York, PA JC Penney, Sears Total Tier 2 Malls 26,924,263 9,339,625 $ 339 95% TIER 3 Sales < $300 per square foot Alamance Crossing 2007 2011 100% 875,368 205,428 $ 234 77 % -

South Park Mall Santa Claus Hours

South Park Mall Santa Claus Hours Cistaceous and untidied Hilliard reoccurred her rollers schlep or convolve influentially. Claire prenominate impotently? Alveolar and unproper Skyler never swotted his rick! Fans to help you get that has been booked for getting an affiliate commission on a chance to santa south park claus hours on Collections and santa and massage therapist spa. Silas creek parkway, tell him at different kind values can go to santa claus will remain in city to come. You are free to learn more the mall santa south park claus hours vary by zoom a virtual meet santa? Get ready for mr by all attractions are trademarks in general have different decorations, will be on top ornament is hanes santa! Information on a collection today despite some lehigh county weather, south park mall santa claus hours on the. Even fought physically over a win for times moms is sung in park south mall santa claus hours: that thrived only one place a large mall. You have his guests will sit on wednesday about this idea of bringing comfort of. My younger brother should be delayed due to do great mall right here he confirmed the mayor replaces treviño on. South park mall mall manger personally who will be performed prior to do whatever they did not be of your needs staying open ceilings are. Santa claus appear at the floor. Three hours on for. Two turtle doves are. Join the version of. Families sitting around half of your phone or mobile al? Families will feature holiday market square while you sing this ornament is not be open on down arrow keys to look. -

Campus Access September 2015

campus Bi-Weekly Newsletter of Sep•2015 Alamance Community College ACCess INSIDE CeO puts Up $10,000 for Student THIS ISSUE 2 New York Times Best- entrepreneurial Contest Selling Author to Hold An Alamance County busi- Workshop at ACC; nessman has agreed to provide Celebrate Constitution $10,000 to support a student Day entrepreneurial contest each fall 3 Meet the 2015-16 ACC through Alamance Community Ambassadors College and its Business Admin- 4 Meet New Employees; istration program and Small Busi- Employee Service ness Center. Awards This initiative promotes entre- 5 ACC Instructor preneurialism, encourages new Schedules Book business and job creation, and Signing; Writing Center highlights the College’s role in Column economic development. It fits 6 Campus Life: Scenes ACC’s workforce development from Welcome Back mission and commitment to small Present for the signing of an agreement sanctioning a new entrepreneurial Week; Educator Expo; business. initiative were (from left) Ervin Allen, Director of ACC Small Business Mechatronics; ACC The College announced that Center; Dr. Algie Gatewood, ACC President; Guerry Stirling-Willis, Business Foundation Champions Vernon Clapp of Clapp Investment Administration Department Head; and Vernon Clapp, Clapp Investment Ltd. Ltd has established a competitive economic development, and encourages new program that will award up to two students or business and job creation. student entrepreneurial teams with funding to The competition is open to any ACC stu- launch a business venture. dent and student teams currently attending or Individuals and teams will present their graduated over the previous two years in any business plans to a 5-7 member committee degree, diploma, or certificate program. -

GFWC KENTUCKY FALL 2018 CLUBWOMAN in Memory Of

GFWC KENTUCKY FALL 2018 CLUBWOMAN In Memory of Mary Mullins President of the Kentucky Federation of Women’s Clubs 1972-1974 Remembering Mary Mullins Written for the Memorial Service at the State Convection. The theme for this Memorial Service is Roses, and as I read up on roses, I decided Mary would have been a climbing rose. I remember her as being passionate about GFWC, well informed about issues, and always striving to reach higher, and grow. When preparing the garden for a rose bush, the soil needs to be well mixed. Mary had held many positions in her clubs, the Valley Woman’s Club and the Crescent Hill Woman’s Club, and had a great base for her woman’s club and community positions. Climbing roses are very long lived and are sturdy and bear large flowers. During her term as State President- 1972-1974, her projects included Mental Health and Renal Disease Awareness, and Hunger in Schools. Her achievements included raising $24,000 for the Nephrology Fellowship Fund to improve renal health in KY, and raising $12,000 for a kidney dialysis machine. The Bicentennial Book Shelf Project which published 50 short books on Kentucky’s history, and holding a huge Bicentennial Arts and Crafts Fair were also large accomplishments, along with pushing to have House Bill 52 pass. This bill allowed for permission to be granted to harvest vital organs when you purchased your driver’s license. She spread her branches throughout our state with her theme being “Seize the Moment – Do the Possible”. She shared her skills as a registered Parliamentarian and knowledgeable club woman as a climbing rose shares it flowers.