Grande Ronde Basin Spring Chinook Salmon Hatchery Review: Introduction and the Early Years

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Synthesis Document

1114 J Ave. October 1, 2018 La Grande, Oregon 97850 (541) 663-0570 Independent Scientific Review Panel Fax: (541) 962-1585 Northwest Power and Conservation Council http://www.grmw.org 851 S.W. Sixth Avenue, Suite 1100 Portland, Oregon 97204 Board of Directors Chair: Dear Panel Members, Susan Roberts Vice-Chair: Donna Beverage We are pleased to submit the 25-year synthesis of the Grande Ronde Model Watershed (GRMW) and hope you find it satisfactory. Although this assignment Allen Childs Norm Cimon might have been accepted begrudgingly, we have found value in taking the time Larry Cribbs to look at the road behind us, if for no other reason than to see if the dust has Jed Hassinger Joe McCormack settled. Nick Myatt Larry Nall Jim Webster It is the nature of organizations like ours to engage in an endless cycle of plan, Dave Yost prioritize, plan, prioritize, and plan some more, often failing to review past actions with a critical eye. This shortcoming might not be as commonplace as I suspect, but having been engaged in the politics and science of this relatively Staff: Mary Estes new ‘industry’ for more than 20 years, I sense that it is not unique to GRMW. I Coby Menton am reminded that this synthesis encapsulates all my career with GRMW and so Kayla Morinaga Jeff Oveson it is a personal reminder of some, but surely not all, of my own shortcomings. Jesse Steele Connar Stone Alexandra Towne If I may be presumptuous, I anticipate that other Umbrella organizations in the Columbia Basin will be tasked with a similar undertaking, and while I hope that our synthesis is not only what the Panel expected, but also can serve as a guide to those who will be preparing their own. -

Snake River Hatcheries Draft Environmental Assessment

UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration NATIONAL MARINE FISHERIES SERVICE West Coast Region 1201 NE Lloyd Boulevard, Suite 1100 PORTLAND, OREGON 97232 May 21, 2019 Dear Recipient: In accordance with provisions of the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA), we announce the availability for review of the Draft Environmental Assessment (DEA) for Snake River Basin Hatcheries. The proposed action is to make Endangered Species Act (ESA) section 4(d) determinations for the 15 hatchery programs for spring and summer Chinook salmon, summer steelhead, and coho salmon to operate in the Snake River Basin. These programs are operated by the Idaho Department of Fish and Game, the Nez Perce Tribe, and the Shoshone-Bannock Tribes and are funded by the Columbia River Inter-Tribal Fish Commission, the Lower Snake River Compensation Plan, the Idaho Power Company, and the Bonneville Power Administration. The document is accessible electronically through the National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) West Coast Region website at: http://www.westcoast.fisheries.noaa.gov/hatcheries/SRHatcheries/snake16_hatch_rvw.html. Hard copies or CD copies of the document may be obtained from the NMFS Comment Coordinator for this action, Emi Kondo, at the contact information provided below. Written comments may be submitted to NMFS via electronic mail, physical mail, or fax to the Comment Coordinator during the public comment period (the closing date for the public comment period is noted at the above website). When submitting comments, please include the identifier “Snake River Hatcheries DEA comments” in the subject line or fax cover page. Comment Coordinator: Emi Kondo, Fish Biologist National Marine Fisheries Service, West Coast Region 1201 NE Lloyd Blvd., Suite 1100 Portland, OR 97232 Phone: 503-736-4739 Fax: 503-872-2737 [email protected] Thank you in advance for your input and assistance in finalizing the Environmental Assessment. -

A Brief History of the Umatilla National Forest

A BRIEFHISTORYOFTHE UMATILLA NATIONAL FOREST1 Compiled By David C. Powell June 2008 1804-1806 The Lewis and Clark Expedition ventured close to the north and west sides of the Umatilla National Forest as they traveled along the Snake and Columbia rivers. As the Lewis & Clark party drew closer to the Walla Walla River on their return trip in 1806, their journal entries note the absence of firewood, Indian use of shrubs for fuel, abundant roots for human consumption, and good availability of grass for horses. Writing some dis- tance up the Walla Walla River, William Clark noted that “great portions of these bottoms has been latterly burnt which has entirely destroyed the timbered growth” (Robbins 1997). 1810-1840 This 3-decade period was a period of exploration and use by trappers, missionaries, natu- ralists, and government scientists or explorers. William Price Hunt (fur trader), John Kirk Townsend (naturalist), Peter Skene Ogden (trap- per and guide), Thomas Nuttall (botanist), Reverend Samuel Parker (missionary), Marcus and Narcissa Whitman (missionaries), Henry and Eliza Spaulding (missionaries), Captain Benjamin Bonneville (military explorer), Captain John Charles Fremont (military scientist), Nathaniel J. Wyeth (fur trader), and Jason Lee (missionary) are just a few of the people who visited and described the Blue Mountains during this era. 1840-1859 During the 1840s and 1850s – the Oregon Trail era – much overland migration occurred as settlers passed through the Blue Mountains on their way to the Willamette Valley (the Oregon Trail continued to receive fairly heavy use until well into the late 1870s). The Ore- gon Trail traversed the Umatilla National Forest. -

Heaven in Hell's Canyon

Northwest Explorer ONDAL ONDAL M M EN EN K K Left: Hiker at the boundary of Hell’s Canyon Wilderness. Right: Approaching Horse Heaven, elevation 8,100 feet on the Seven Devils Loop Trail in Hell’s Canyon Wilderness. June and July are good times to explore Washington’s southeast corner in the Wenaha-Tucannon area and in the nearby Hells Canyon area of Oregon and Idaho. Heaven in Hell’s Canyon Hiking two wilderness areas near Washington’s southeast corner By Ken Mondal finding places to backpack when the high jaw-dropping views. This hike can be country is snowed in. The Imnaha River done comfortably in 3-4 days. Seven Devils Loop in Hell’s is hikable virtually year round. An excellent description of hiking the Canyon is Heavenly On the Idaho side of the recreation Seven Devils Loop can be found in Hik- There is no question that the Grand area is a 215,000-acre wilderness area, ing Idaho by Maughan and Maughan, Canyon is one of the natural wonders which includes the Seven Devils Moun- published by Falcon. For the other hikes of the world. However, if one measures tains. The premier hike within this I would recommend Rich Landers’ 100 from the Snake River to the summit of wilderness is the Seven Devils Loop, a Hikes in the Inland Northwest. 9,393 foot He Devil Peak in the Seven rugged 29-mile round trip offering mag- Devils Mountains, this makes Hells nificent views into Hells Canyon many Choose Forgotten Wenaha- Canyon the deepest canyon in North thousands of feet below and equally Tucannon for Solitude America. -

Assessing the Status and Trends of Spring Chinook Habitat in the Upper Grande Ronde River and Catherine Creek: Annual Report 2018 Publication Date: April 30, 2019

Assessing the Status and Trends of Spring Chinook Habitat in the Upper Grande Ronde River and Catherine Creek: Annual Report 2018 publication date: April 30, 2019 Authors: Seth White, Casey Justice, Lauren Burns, David Graves, Denise Kelsey, and Matthew Kaylor Technical Report 19-04 Columbia River Inter-Tribal Fish Commission 700 NE Multnomah St, Ste 1200, Portland OR 97232 · (503)238-0667 · www.critfc.org Funding for this work came from the Columbia Basin Fish Accords (2008-2018), a ten-year tribal/federal partnership between the Bonneville Power Administration, Bureau of Reclamation, Columbia River Inter-Tribal Fish Commission, The Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation, The Confederated Tribes of the Warm Springs Reservation of Oregon, US Army Corps of Engineers, and The Confederated Tribes and Bands of the Yakama Nation. Assessing the Status and Trends of Spring Chinook Habitat in the Upper Grande Ronde River and Catherine Creek BPA Project # 2009-004-00 Report covers work performed under BPA contract #(s) 75586, 73354 REL 2 Report was completed under BPA contract #(s) 73354 REL 2 Report covers work performed from: January – December 2018 Seth White1,2, Casey Justice1, Lauren Burns1, David Graves1, Denise Kelsey1, and Matthew Kaylor2 1Columbia River Inter-Tribal Fish Commission, Portland, OR 97232 2Department of Fisheries & Wildlife, Oregon State University, Corvallis, OR 97331 April 2019 This report was funded by the Bonneville Power Administration (BPA), U.S. Department of Energy, as part of BPA's program to protect, mitigate, and enhance fish and wildlife affected by the development and operation of hydroelectric facilities on the Columbia River and its tributaries. -

Snake River Flow Augmentation Impact Analysis Appendix

SNAKE RIVER FLOW AUGMENTATION IMPACT ANALYSIS APPENDIX Prepared for the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Walla Walla District’s Lower Snake River Juvenile Salmon Migration Feasibility Study and Environmental Impact Statement United States Department of the Interior Bureau of Reclamation Pacific Northwest Region Boise, Idaho February 1999 Acronyms and Abbreviations (Includes some common acronyms and abbreviations that may not appear in this document) 1427i A scenario in this analysis that provides up to 1,427,000 acre-feet of flow augmentation with large drawdown of Reclamation reservoirs. 1427r A scenario in this analysis that provides up to 1,427,000 acre-feet of flow augmentation with reservoir elevations maintained near current levels. BA Biological assessment BEA Bureau of Economic Analysis (U.S. Department of Commerce) BETTER Box Exchange Transport Temperature Ecology Reservoir (a water quality model) BIA Bureau of Indian Affairs BID Burley Irrigation District BIOP Biological opinion BLM Bureau of Land Management B.P. Before present BPA Bonneville Power Administration CES Conservation Extension Service cfs Cubic feet per second Corps U.S. Army Corps of Engineers CRFMP Columbia River Fish Mitigation Program CRP Conservation Reserve Program CVPIA Central Valley Project Improvement Act CWA Clean Water Act DO Dissolved Oxygen Acronyms and Abbreviations (Includes some common acronyms and abbreviations that may not appear in this document) DREW Drawdown Regional Economic Workgroup DDT Dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane EIS Environmental Impact Statement EP Effective Precipitation EPA Environmental Protection Agency ESA Endangered Species Act ETAW Evapotranspiration of Applied Water FCRPS Federal Columbia River Power System FERC Federal Energy Regulatory Commission FIRE Finance, investment, and real estate HCNRA Hells Canyon National Recreation Area HUC Hydrologic unit code I.C. -

Chapter 16. Mid-Columbia Recovery Unit—Grande Ronde River Critical Habitat Unit

Bull Trout Final Critical Habitat Justification: Rationale for Why Habitat is Essential, and Documentation of Occupancy Chapter 16. Mid-Columbia Recovery Unit—Grande Ronde River Critical Habitat Unit 447 Bull Trout Final Critical Habitat Justification Chapter 16 U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service September 2010 Chapter 16. Grande Ronde River Critical Habitat Unit The Grande Ronde River CHU is essential to the conservation of bull trout because is supports strong bull trout populations and provides high-quality habitat to potentially expand bull trout distribution and is considered to be essential for bull trout recovery in the Mid-Columbia RU. The eleven populations in this CHU are spread over a large geographical area with multiple age classes, containing both resident and fluvial fish. This bull trout stronghold also has a prey base; connectivity with the Snake River; general distribution of bull trout throughout the habitat; and varying habitat conditions. But in several of the populations, including the Wenaha River, Lostine River, Lookingglass Creek, and Little Minam River populations, excellent habitat conditions exist; many streams and rivers are designated as Wild and Scenic Rivers and/or located within or near Wilderness areas. Two wilderness areas are designated within the Grande Ronde River basin. The Eagle Cap Wilderness is located in the Wallowa-Whitman National Forest, encompasses 146,272 (ha) (361,446 ac), and includes most of the Minam, upper Wallowa and Lostine river drainages as well as Bear Creek and Hurricane Creek and a small portion of Catherine Creek. Federal Wild and Scenic River status is designated for the Lostine and Minam Rivers and Oregon State Scenic Waterway status is designated to the Minam and Wallowa Rivers. -

Explosion Structures in Grande Ronde Basalt of the Columbia Riverbasalt Group, Near Troy, Oregon

Portland State University PDXScholar Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses 1987 Explosion structures in Grande Ronde basalt of the Columbia Riverbasalt group, near Troy, Oregon Leonard Lee Orzol Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/open_access_etds Part of the Geology Commons, and the Volcanology Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Orzol, Leonard Lee, "Explosion structures in Grande Ronde basalt of the Columbia Riverbasalt group, near Troy, Oregon" (1987). Dissertations and Theses. Paper 3750. https://doi.org/10.15760/etd.5634 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. AN ABSTRAST OF THE THESIS OF Leonard Lee Orzol for the Master of Science in Geology presented June 12, 1987. Title: Explosion Structures in Grande Ronde Basalt of the Columbia River Basalt Group, near Troy, Oregon. APPROVED BY MEMBERS OF THE THESIS COMMITEE: vin H. Beeson Explosion structures occur in flows of Grande Ronde Basalt in the study area near Troy, Oregon. Data from nineteen stratigraphic sites indicate that the maximum number of flows that contain explosion structures at any one site is six. In the informally named Troy flow, explosion structures are widespread. Each flow that contains explosion structures can be divided into two cooling units. The first cooling units occupy troughs in the pre-eruption topography and are up to 10 meters thick. -

1 Dennis Dauble Game & Fish Magazine July/August

Dennis Dauble Game & Fish Magazine July/August 2013 Hike Into Trout on the Wenaha Here’s the scenario: three 57-somethings on a backpacking adventure to trout waters nestled deep within the Blue Mountains of northeastern Oregon. The first step of our journey took us to a forested trailhead overlooking the Wenaha River. It was early August and 90 F at high noon. Three miles, six switchbacks, several piles of bear scat and a quart of water later we reached the river and started to fish. As it turned out, the first few hours were uneventful. I hooked and lost one rainbow trout after swapping out a Renegade for a Stimulator then a Bucktail Royal Coachman (All standard patterns that worked on the west side of the Blues). Ken caught two 13-inch trout on a Parachute Adams and Ted enticed a 4-incher to an unnamed pattern he tied himself. While working our way downstream to base camp, we experienced a violent thunderstorm and got drenched. The seed for this hike-and-fish adventure found fertile ground after being planted on two long-time friends during a microbrew moment. Our preparation mirrored respective personalities. Ted shaped up by hiking Badger Mountain with a pack full of rocks. I carried my golf clubs around the course for several rounds. Ken, a regular visitor to a court club, followed his wife around the shopping mall. Otherwise, we relied on zip- off leg pants for everyday wear, closed-toe sandals for wading and trusted that our ancient Boy Scout mess kits still had utility. -

Field-Trip Guide to the Vents, Dikes, Stratigraphy, and Structure of the Columbia River Basalt Group, Eastern Oregon and Southeastern Washington

Field-Trip Guide to the Vents, Dikes, Stratigraphy, and Structure of the Columbia River Basalt Group, Eastern Oregon and Southeastern Washington Scientific Investigations Report 2017–5022–N U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Cover. Palouse Falls, Washington. The Palouse River originates in Idaho and flows westward before it enters the Snake River near Lyons Ferry, Washington. About 10 kilometers north of this confluence, the river has eroded through the Wanapum Basalt and upper portion of the Grande Ronde Basalt to produce Palouse Falls, where the river drops 60 meters (198 feet) into the plunge pool below. The river’s course was created during the cataclysmic Missoula floods of the Pleistocene as ice dams along the Clark Fork River in Idaho periodically broke and reformed. These events released water from Glacial Lake Missoula, with the resulting floods into Washington creating the Channeled Scablands and Glacial Lake Lewis. Palouse Falls was created by headward erosion of these floodwaters as they spilled over the basalt into the Snake River. After the last of the floodwaters receded, the Palouse River began to follow the scabland channel it resides in today. Photograph by Stephen P. Reidel. Field-Trip Guide to the Vents, Dikes, Stratigraphy, and Structure of the Columbia River Basalt Group, Eastern Oregon and Southeastern Washington By Victor E. Camp, Stephen P. Reidel, Martin E. Ross, Richard J. Brown, and Stephen Self Scientific Investigations Report 2017–5022–N U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior RYAN K. ZINKE, Secretary U.S. -

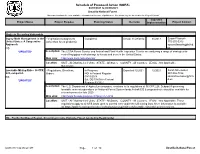

Schedule of Proposed Action (SOPA) 04/01/2021 to 06/30/2021 Umatilla National Forest This Report Contains the Best Available Information at the Time of Publication

Schedule of Proposed Action (SOPA) 04/01/2021 to 06/30/2021 Umatilla National Forest This report contains the best available information at the time of publication. Questions may be directed to the Project Contact. Expected Project Name Project Purpose Planning Status Decision Implementation Project Contact Projects Occurring Nationwide Gypsy Moth Management in the - Vegetation management Completed Actual: 11/28/2012 01/2013 Susan Ellsworth United States: A Cooperative (other than forest products) 775-355-5313 Approach [email protected]. EIS us *UPDATED* Description: The USDA Forest Service and Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service are analyzing a range of strategies for controlling gypsy moth damage to forests and trees in the United States. Web Link: http://www.na.fs.fed.us/wv/eis/ Location: UNIT - All Districts-level Units. STATE - All States. COUNTY - All Counties. LEGAL - Not Applicable. Nationwide. Locatable Mining Rule - 36 CFR - Regulations, Directives, In Progress: Expected:12/2021 12/2021 Sarah Shoemaker 228, subpart A. Orders NOI in Federal Register 907-586-7886 EIS 09/13/2018 [email protected] d.us *UPDATED* Est. DEIS NOA in Federal Register 03/2021 Description: The U.S. Department of Agriculture proposes revisions to its regulations at 36 CFR 228, Subpart A governing locatable minerals operations on National Forest System lands.A draft EIS & proposed rule should be available for review/comment in late 2020 Web Link: http://www.fs.usda.gov/project/?project=57214 Location: UNIT - All Districts-level Units. STATE - All States. COUNTY - All Counties. LEGAL - Not Applicable. These regulations apply to all NFS lands open to mineral entry under the US mining laws. -

ESA Recovery Plan for Snake River Spring/Summer Chinook Salmon (Oncorhynchus Tshawytscha) & Snake River Basin Steelhead (Oncorhynchus Mykiss)

ESA Recovery Plan for Snake River Spring/Summer Chinook Salmon (Oncorhynchus tshawytscha) & Snake River Basin Steelhead (Oncorhynchus mykiss) November 2017 WEST COAST REGION Chinook salmon at Dagger Falls, Idaho. Photo: Enrique Patino, NOAA U.S. Department of Commerce | National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration | National Marine Fisheries Service ESA Recovery Plan: Snake River Spring/Summer Chinook Salmon and Snake River Basin Steelhead| 1 DISCLAIMER Endangered Species Act (ESA) recovery plans delineate reasonable actions that the best available information indicates are necessary for the conservation and survival of listed species. Plans are published by the National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS), usually with the assistance of recovery teams, state agencies, tribes, local governments, salmon recovery boards, non-governmental organizations, interested citizens of the affected area, contractors, and others. ESA recovery plans do not necessarily represent the views, official positions, or approval of any individuals or agencies involved in the plan formulation, other than NMFS. They represent the official position of NMFS only after they have been signed by the West Coast Regional Administrator. ESA recovery plans are guidance and planning documents only; identification of an action to be implemented by any public or private party does not create a legal obligation beyond existing legal requirements. Nothing in this plan should be construed as a commitment or requirement that any Federal agency obligate or pay funds in any one fiscal year in excess of appropriations made by Congress for that fiscal year in contravention of the Anti-Deficiency Act, 31 U.S.C. 1341, or any other law or regulation. Approved recovery plans are subject to modification as dictated by new information, changes in species status, and the completion of recovery actions.