Telling Stories to Anybody Who Will Listen: an Interview with Robert Colón

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Song List 2012

SONG LIST 2012 www.ultimamusic.com.au [email protected] (03) 9942 8391 / 1800 985 892 Ultima Music SONG LIST Contents Genre | Page 2012…………3-7 2011…………8-15 2010…………16-25 2000’s…………26-94 1990’s…………95-114 1980’s…………115-132 1970’s…………133-149 1960’s…………150-160 1950’s…………161-163 House, Dance & Electro…………164-172 Background Music…………173 2 Ultima Music Song List – 2012 Artist Title 360 ft. Gossling Boys Like You □ Adele Rolling In The Deep (Avicii Remix) □ Adele Rolling In The Deep (Dan Clare Club Mix) □ Afrojack Lionheart (Delicious Layzas Moombahton) □ Akon Angel □ Alyssa Reid ft. Jump Smokers Alone Again □ Avicii Levels (Skrillex Remix) □ Azealia Banks 212 □ Bassnectar Timestretch □ Beatgrinder feat. Udachi & Short Stories Stumble □ Benny Benassi & Pitbull ft. Alex Saidac Put It On Me (Original mix) □ Big Chocolate American Head □ Big Chocolate B--ches On My Money □ Big Chocolate Eye This Way (Electro) □ Big Chocolate Next Level Sh-- □ Big Chocolate Praise 2011 □ Big Chocolate Stuck Up F--k Up □ Big Chocolate This Is Friday □ Big Sean ft. Nicki Minaj Dance Ass (Remix) □ Bob Sinclair ft. Pitbull, Dragonfly & Fatman Scoop Rock the Boat □ Bruno Mars Count On Me □ Bruno Mars Our First Time □ Bruno Mars ft. Cee Lo Green & B.O.B The Other Side □ Bruno Mars Turn Around □ Calvin Harris ft. Ne-Yo Let's Go □ Carly Rae Jepsen Call Me Maybe □ Chasing Shadows Ill □ Chris Brown Turn Up The Music □ Clinton Sparks Sucks To Be You (Disco Fries Remix Dirty) □ Cody Simpson ft. Flo Rida iYiYi □ Cover Drive Twilight □ Datsik & Kill The Noise Lightspeed □ Datsik Feat. -

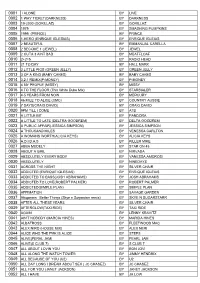

DJ Playlist.Djp

0001 I ALONE BY LIVE 0002 1 WAY TICKET(DARKNESS) BY DARKNESS 0003 19-2000 (GORILLAZ) BY GORILLAZ 0004 1979 BY SMASHING PUMPKINS 0005 1999 (PRINCE) BY PRINCE 0006 1-HERO (ENRIQUE IGLESIAS) BY ENRIQUE IGLEIAS 0007 2 BEAUTIFUL BY EMMANUAL CARELLA 0008 2 BECOME 1 (JEWEL) BY JEWEL 0009 2 OUTA 3 AINT BAD BY MEATFLOAF 0010 2+2=5 BY RADIO HEAD 0011 21 TO DAY BY HALL MARK 0012 3 LITTLE PIGS (GREEN JELLY) BY GREEN JELLY 0013 3 OF A KIND (BABY CAKES) BY BABY CAKES 0014 3,2,1 REMIX(P-MONEY) BY P-MONEY 0015 4 MY PEOPLE (MISSY) BY MISSY 0016 4 TO THE FLOOR (Thin White Duke Mix) BY STARSIALER 0017 4-5 YEARS FROM NOW BY MERCURY 0018 46 MILE TO ALICE (CMC) BY COUNTRY AUSSIE 0019 7 DAYS(CRAIG DAVID) BY CRAIG DAVID 0020 9PM TILL I COME BY ATB 0021 A LITTLE BIT BY PANDORA 0022 A LITTLE TO LATE (DELTRA GOODREM) BY DELTA GOODREM 0023 A PUBLIC AFFAIR(JESSICA SIMPSON) BY JESSICA SIMPSON 0024 A THOUSAND MILES BY VENESSA CARLTON 0025 A WOMANS WORTH(ALICIA KEYS) BY ALICIA KEYS 0026 A.D.I.D.A.S BY KILLER MIKE 0027 ABBA MEDELY BY STAR ON 45 0028 ABOUT A GIRL BY NIRVADA 0029 ABSOLUTELY EVERY BODY BY VANESSA AMOROSI 0030 ABSOLUTELY BY NINEDAYS 0031 ACROSS THE NIGHT BY SILVER CHAIR 0032 ADDICTED (ENRIQUE IGLESIAS) BY ENRIQUE IGLEIAS 0033 ADDICTED TO BASS(JOSH ABRAHAMS) BY JOSH ABRAHAMS 0034 ADDICTED TO LOVE(ROBERT PALMER) BY ROBERT PALMER 0035 ADDICTED(SIMPLE PLAN) BY SIMPLE PLAN 0036 AFFIMATION BY SAVAGE GARDEN 0037 Afropeans Better Things (Skye n Sugarstarr remix) BY SKYE N SUGARSTARR 0038 AFTER ALL THESE YEARS BY SILVER CHAIR 0039 AFTERGLOW(TAXI RIDE) BY TAXI RIDE -

Black Rage VI Denison University

Denison University Denison Digital Commons Writing Our Story Black Studies 2005 Black Rage VI Denison University Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.denison.edu/writingourstory Recommended Citation Denison University, "Black Rage VI" (2005). Writing Our Story. 98. http://digitalcommons.denison.edu/writingourstory/98 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Black Studies at Denison Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Writing Our Story by an authorized administrator of Denison Digital Commons. ~It ...... 1 ei ll e:· CU· st. C jll eli [I C,I ei l .J C.:a, •.. a4 II a.il .. a,•• as II at iI Uj 'I Uj iI ax cil ui 11 a: c''. iI •a; a,iI'. u,· u,•• a: • at , 3,,' .it Statement of Purpose: To allow for a creative outlet for students of the Black Student Union of Denison University. Dedicated to Introduction The Black Student Union The need for this publication came about when the expres· Spring 2005 sions of a number of Black students were denied from other campus publications without any valid justification. As his tory has proven, when faced With limitations, we as Black people then create a means for overcoming that limitation a means that is significant to our own interests and beliefs. Therefore, we came together as a Black community in search of resolution, and decided on Black Rage as the instrument by which we would let our creative voices sing. This unprecedented publication serves as a refuge for the Black students at Denison University, by offering an avenue for our poetry, prose, short stories as well as other unique writings to be read, respected, and held in utmost regard. -

SONGS from the OTHER SIDE of the WALL Dan Holloway

SONGS FROM THE OTHER SIDE OF THE WALL Dan Holloway Songs From the Other Side of the Wall has appeared in various and incomplete forms on the websites www.youwriteon.com, www.authonomy.com. It is available to download as a pdf from www.danholloway.wordpress.com and www.yearzerowriters.wordpress.com. 2009, first print edition published by Cracked Egg, and proud to be associated with Year Zerø Writers Songs from the Other Side of the Wall © copyright Dan Holloway 2009 The author asserts the moral right to be named as author of the work Cover design and photograph © 2009 Sarah E Melville Dan Holloway studied theology and philosophy at Oxford, and still gives papers based on his doctoral research into identity and relationships, the themes that run through his books. At the height of the budget travel boom, he and his wife visited 23 countries in a single year, the recounting of which began his ventures into writing full-length novels, his fascination with modern Europe, and the love of Tokaji wine which inspired two of his novels, including this one. His short stories have appeared in Emprise Review and a number of anthologies, and he writes a regular column on the UK music scene for the online journal The Indie Handbook. Songs from the Other Side of the Wall was a number one book on the leading writers’ websites Youwriteon and Authonomy, and is his third completed novel. Dan has a morbid addiction to appearing on TV gameshows, and in 2000 was both the World Intelligence Champion, and the fourth member of the Oxford University discus and hammer throwing team. -

Jamming As a Curriculum of Resistance: Popular Music, Shared Intuitive Headspaces, and Rocking in the "Free" World

Georgia Southern University Digital Commons@Georgia Southern Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies, Jack N. Averitt College of Spring 2015 Jamming as a Curriculum of Resistance: Popular Music, Shared Intuitive Headspaces, and Rocking in the "Free" World Mike Czech Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/etd Part of the Art Education Commons, and the Curriculum and Instruction Commons Recommended Citation Czech, Mike, "Jamming as a Curriculum of Resistance: Popular Music, Shared Intuitive Headspaces, and Rocking in the "Free" World" (2015). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 1270. https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/etd/1270 This dissertation (open access) is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies, Jack N. Averitt College of at Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. For more information, please contact [email protected]. JAMMING AS A CURRICULUM OF RESISTANCE: POPULAR MUSIC, SHARED INTUITIVE HEADSPACES, AND ROCKING IN THE “FREE” WORLD by MICHAEL R. CZECH (Under the Direction of John Weaver) ABSTRACT This project opens space for looking at the world in a musical way where “jamming” with music through playing and listening to it helps one resist a more standardized and dualistic way of seeing the world. Instead of having a traditional dissertation, this project is organized like a record album where each chapter is a Track that contains an original song that parallels and plays off the subject matter being discussed to make a more encompassing, multidimensional, holistic, improvisational, and critical statement as the songs and riffs move along together to tell why an arts-based musical way of being can be a choice and alternative in our lives. -

Ian Tyson Ian Tyson

WINTER 2010 Ian Tyson The singer/songwriter shares his life and music in The Long Trail Mojave Desert Trail Ride Steve Thornton’s Winter Portfolio The Living Words of the Constitution Part 13 Display until March 15 www.paragonfoundation.org $5.95 US The Journal of the PARAGON Foundationion,, Inc.Inc. OUR MISSION The PARAGON Foundation provides for education, research and the exchange of ideas in an effort to promote and support Constitutional principles, individual freedoms, private property rights and the continuation of rural customs and culture – all with the intent of celebrating and continuing our Founding Fathers vision for America. The PARAGON Foundation, Inc. • To Educate and Empower We invit e you to join us. www.paragonfoundation.org photo by Steve Thornton IN THIS ISSUE 12 88 Of Note Charreria Current Events and Culture The Forerunner of from Out West American Rodeo By Guy de Galard 40 The Cowboy Way Profile 92 Don Edwards Riding the Mojave By Darrell Arnold An Out Back Adventure By Mark Bedor 45 R-CALF USA 96 Special Section Ranch Living Life on the Ranch with Thea Marx 53 American Agri-Women 101 Special Section Great White Western Shirts A Portfolio 55 Photography byWilliam Reynolds Big Doin’s in Cow Town The Legendary Fort Worth 109 Stock Show The Magnificent Seven at 50 By Mark Bedor A Remembrance By T.X. “Tex” Brown 59 FFA 114 Special Section Range Writing Cowboy Poetry from 66 All Over the West Your Rights By Daniel Martinez 116 Recommended Reading 70 Old and New Books The Living Words Worthy of Your Nightstand of the Constitution By Nicole Krebs 119 PARAGON Memorials 73 Winter in the West 120 A Steve Thornton Portfolio Out There 83 America: Where the Power Resides Cover photograph of Ian Tyson Best Overall Part One: Common Law Courtesy Ian Tyson and Mascioli Publication 2009 Entertainment photo photo by Steve Thornton By Marilyn Fisher WINTER 2010 VOLuME 6 NO. -

Reproductions Supplied by EDRS Are the Best That Can Be Made from the Original Document

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 452 104 SO 031 665 AUTHOR Harris, Laurie Lanzen, Ed.; Abbey, Cherie D., Ed. TITLE Biography Today: Profiles of People of Interest to Young Readers, 2000. ISSN ISSN-1058-2347 PUB DATE 2000-00-00 NOTE 504p. AVAILABLE FROM Omnigraphics, 615 Griswold Street, Detroit, MI 48226 (one year subscription: three softbound issues, $55; hardbound annual compendium, $75; individual volumes, $39). Tel: 800-234-1340 (Toll Free); Fax: 800-875-1340 (Toll Free); Web site: http://www.omnigraphics.com/. PUB TYPE Collected Works Serials (022) Reference Materials General (130) JOURNAL CIT Biography Today; v9 n1-3 Jan-Sept 2000 EDRS PRICE MF02/PC21 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Adolescent Literature; Biographies; Childrens Literature; Elementary Secondary Education; Individual Characteristics; Life Events; Popular Culture; *Profiles; Readability; Role Models; Social Studies; Student Interests IDENTIFIERS *Biodata; Obituaries ABSTRACT This is the ninth volume of a series designed and written for young readers ages 9 and above. It contains three issues and profiles individuals whom young people want to know about most: entertainers, athletes, writers, illustrators, cartoonists, and political leaders. The publication was created to appeal to young readers in a format they can enjoy reading and readily understand. Each entry provides at least one picture of the individual profiled, and bold-faced rubrics lead the reader to information on birth, youth, early memories, education, first jobs, marriage and family, career highlights, memorable experiences, hobbies, and honors and awards. Each entry ends with a list of easily accessible sources (both print and electronic) designed to guide the student to further reading on the individual. Obituary entries also are included, written to provide a perspective on an individual's entire career. -

IT's DIFFERENT with PUPPETS a Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of Ohio University in Parti

IT’S DIFFERENT WITH PUPPETS A thesis presented to the faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts Lydia M. McDermott June 2007 This thesis entitled IT’S DIFFERENT WITH PUPPETS by LYDIA M. MCDERMOTT has been approved for the Department of English and the College of Arts and Sciences by Sharmila A. Voorakkara Assistant Professor of English Benjamin M. Ogles Dean, College of Arts and Sciences Abstract MCDERMOTT, LYDIA M., M.A., June 2007, English IT’S DIFFERENT WITH PUPPETS (91 pp.) Director of Thesis: Sharmila Voorakkara This is a collection of poetry preceded by a critical introduction entitled, “Cleaving the Body to/from/in My Poems: A Critical Introduction.” The introduction explores the way in which I use the female body within my poems to validate a space for this body in literature. I compare and contrast my poems to the poems of Sharon Olds, Denise Duhamel, and Beth Ann Fennely, to name a few. The creative portion of the thesis deals with the subject of the female body in many arenas, but is not limited to this subject. Approved: ____________________________________________________________ Sharmila Voorakkara Assistant Professor of English To my children, Fionn and Sawyer. Acknowledgements I would like to thank my husband, Michael Ensor. Without his constant support as husband and as father, I never could have finished this manuscript. I’d also like to thank my two sons, Fionn and Sawyer, who have been ever patient with their mother and provided a lot of the material for my poetry. -

![[ ALTERNATIVE by ARTIST ] [ No of Tunes = 408 ] 28 DAYS >> SONG](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9812/alternative-by-artist-no-of-tunes-408-28-days-song-3289812.webp)

[ ALTERNATIVE by ARTIST ] [ No of Tunes = 408 ] 28 DAYS >> SONG

[ ALTERNATIVE by ARTIST ] [ No of Tunes = 408 ] 28 DAYS >> SONG FOR JASMINE 28 DAYS >> SUCKER 3 DOORS DOWN >> KRYPTONITE {K} 3OH!3 >> DON'T TRUST ME 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER >> SHE'S KINDA HOT {K} 50 CENT >> PLACES TO GO A >> STARBUCKS ALIEN ANT FARM >> GLOW ALIEN ANT FARM >> MOVIES ALIEN ANT FARM >> SMOOTH CRIMINAL {K} ALL AMERICAN REJECTS >> GIVES YOU HELL {K} ANDREW W K >> WE WANT FUN ANDROIDS >> DO IT WITH MADONNA {K} ARCTIC MONKEYS >> I BET YOU LOOK GOOD ON THE DANCE FLOOR AREA 7 >> START MAKING SENSE ASHLEE SIMPSON >> LA LA {K} AVRIL LAVIGNE >> GIRLFRIEND {K} AVRIL LAVIGNE >> HERE'S TO NEVER GROWING UP {K} AVRIL LAVIGNE >> MY HAPPY ENDING {K} AVRIL LAVIGNE >> SK8ER BOI {K} AVRIL LAVIGNE >> SMILE {K} BABY ANIMALS >> RUSH YOU BEASTIE BOYS >> BODY MOVIN BEASTIE BOYS >> INTERGALATIC BEN FOLDS FIVE >> ROCKIN' THE SUBURBS BIG AUDIO DYNAMITE >> RUSH BLACK KEYS >> LONELY BOY {K} BLIND MELON >> NO RAIN BLINK 182 >> ALL THE SMALL THINGS {K} BLINK 182 >> BORED TO DEATH BLINK 182 >> DAMMIT BLINK 182 >> I MISS YOU {K} BLINK 182 >> MAN OVERBOARD {K} BLINK 182 >> ROCK SHOW BLINK 182 >> WHAT'S MY AGE BLOODHOUND GANG >> FIRE WATER BURN BLUR >> CRAZY BEAT BLUR >> SONG 2 BODY ROCKERS >> I LIKE THE WAY {K} BODYJAR >> FALL TO THE GROUND {K} BODYJAR >> TOO DRUNK TO DRIVE BUSTED >> WHAT I GO TO SCHOOL FOR CAKE >> SHORT SKIRT - LONG JACKET CALLING >> OUR LIVES CARDIGANS >> MY FAVOURITE GAME CITIZEN KING >> BETTER DAYS COLDPLAY >> DON'T PANIC COLDPLAY >> EVERY TEARDROP IS A WATERFALL COLDPLAY >> PARADISE COLDPLAY >> SPEED OF SOUND {K} COLDPLAY >> TALK {K} CORNERSHOP -

Audiojuke Music List 11/12

Cliffhangers DIGITAL JUKEBOX Song list www.cliffhangers.com.au All 3000+ songs are included with our Digital Jukeboxes. For Karaoke songs on our jukeboxes please download our Karaoke song list. These are available in addition to the normal AUDIO ONLY tracks below. PH: (07) 55 942 900 Red is 50s&60s tracks, Yellow is 70s tracks, Blue is 80s tracks ..this will help you ( ) 10CC - DREADLOCK HOLIDAY ( ) Agnes – I NEED YOU NOW(RADIO EDIT) ( ) 112 - DANCE WITH ME ( ) Agnes – RELEASE ME ( ) 2 PAC – CALIFORNIA LOVE ( ) Aguilera/Pink/Mya - LADY MARMALADE ( ) 2 PAC – CHANGES ( ) Air – LA FEMME DARGENT ( ) 2 Pac – GHETTO GOSPEL ( ) Akon - ANGEL ( ) 28 Days - RIP IT UP ( ) Akon ft Colby O'Donis & Kardinal Offishall - BEAUTIFUL ( ) 28 Days - SAY WHAT ( ) Akon – DON'T MATTER ( ) 3oh!3 – DON'T TRUST ME ( ) Akon – SORRY, BLAME IT ON ME ( ) 3oh!3 – DOUBLE VISION ( ) Akon – LONELY ( ) 3OH!3 – STARSTRUKK ( ) Akon feat Eminem – SMACK THAT ( ) 3OH!3 feat Ke$ha – MY FIRST KISS ( ) Akon ft Keri Hilson – OH AFRICA ( ) 360FT Gossing – BOYS L;IKE YOU (clean) ( ) Akon feat Snoop Dogg – I WANNA LOVE YOU ( ) 30 Seconds to Mars-CLOSER TO THE EDGE ( ) Alan Jackson - DON’T ROCK THE JUKEBOX ( ) 30 Seconds to Mars – THE KILL (BURY ME) ( ) Alanis Morrisette - HAND IN MY POCKET ( ) 3 Doors Down – IT'S NOT MY TIME ( ) Alanis Morrisette - HANDS CLEAN ( ) 3 Doors Down – HERE WITHOUT YOU ( ) Alanis Morrisette – IRONIC ( ) 3 Doors Down – KYPTONITE ( ) Alcazar - CRYING AT THE DISCOTEQUE ( ) 3LW - NO MORE (BABY IMA DO U RITE) ( ) Alesha Dixon – THE BOY DOES NOTHING ( ) 4 Non Blondes -

![PARTY LISTENING MUSIC by TUNE ]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8157/party-listening-music-by-tune-3628157.webp)

PARTY LISTENING MUSIC by TUNE ]

[ PARTY LISTENING MUSIC by TUNE ] 1 THING by Amerie {Karaoke} 20 GOOD REASONS by Thirsty Merc {Karaoke} 22 STEPS by Damien Leith 3AM by Matchbox 20 {Karaoke} 4 IN THE MORNING by Gwen Stefani {Karaoke} 9PM ( TILL I COME ) by A T B A HARD RAIN'S A - GONNA FALL by Bryan Ferry And Roxy Music A LITTLE TOO LATE by Delta Goodrem {Karaoke} A NEW DAY HAS COME by Celine Dion {Karaoke} A PUBLIC AFFAIR by Jessica Simpson A THOUSAND MILES by Vanessa Carlton {Karaoke} A TOWN CALLED MALICE by The Jam ACCIDENTALLY IN LOVE by Counting Crows {Karaoke} ADDICTED by Simple Plan {Karaoke} ADDICTED TO BASS by Puretone ADDICTED TO LOVE by Robert Palmer {Karaoke} ADDICTED TO YOU by Anthony Callea {Karaoke} ADVERTISING SPACE by Robbie Williams AIN'T NO MOUNTAIN HIGH ENOUGH by Jimmy Barnes ALL FOR YOU by Janet Jackson ALL I NEED IS YOU by Guy Sabastian {Karaoke} ALL I WANNA DO by Jo Jo Zep And The Falcons ALL I WANNA DO by Sheryl Crow {Karaoke} ALL MY LOVE by Led Zeppelin ALL NIGHT by Janet Jackson ALL NIGHT LONG by Lionel Richie ALL RIGHT NOW by Free {Karaoke} ALL SEATS TAKEN by Bec Cartright ALL THAT SHE WANTS by Ace Of Base {Karaoke} ALRIGHT by Supergrass ALWAYS BE WITH YOU by Human Nature AMAZING by Alex Lloyd {Karaoke} AMAZING by George Michael AMERICAN PIE by Don Mc Lean {Karaoke} AMERICAN PIE by Madonna AND SHE WAS by Talking Heads ANGEL by Amanda Perez {Karaoke} ANGEL by Shaggy {Karaoke} ANGEL EYES by Paulini {Karaoke} ANGELS BROUGHT ME HERE by Guy Sebastian {Karaoke} ANOTHER BRICK IN THE WALL by Pink Floyd {Karaoke} ANOTHER CHANCE by Roger Sanchez {Karaoke} -

Party Warehouse Karaoke & Jukebox Song List

Party Warehouse Karaoke & Jukebox Song List Please note that this is a sample song list from one Karaoke & Jukebox Machine which may vary from the one you hire You can view a sample song list for digital jukebox (which comes with the karaoke machine) below. Song# ARTIST TRACK NAME 1 10CC IM NOT IN LOVE Karaoke 2 10CC DREADLOCK HOLIDAY Karaoke 3 2 PAC CALIFORNIA LOVE Karaoke 4 4 NON BLONDES WHATS UP Karaoke 5 50 CENT IN DA CLUB Karaoke 6 A HA TAKE ON ME Karaoke 7 A HA THE SUN ALWAYS SHINES ON TV Karaoke 8 A1 CAUGHT IN THE MIDDLE Karaoke 9 AALIYAH I DONT WANNA Karaoke 10 ABBA DANCING QUEEN Karaoke 11 ABBA WATERLOO Karaoke 12 ABBA THANK YOU FOR THE MUSIC Karaoke 13 ABBA SUPER TROUPER Karaoke 14 ABBA SOS Karaoke 15 ABBA ROCK ME Karaoke 16 ABBA MONEY MONEY MONEY Karaoke 17 ABBA MAMMA MIA Karaoke 18 ABBA KNOWING ME KNOWING YOU Karaoke 19 ABBA FERNANDO Karaoke 20 ABBA CHIQUITITA Karaoke 21 ABBA I DO I DO I DO I DO I DO Karaoke 22 ABC POISON ARROW Karaoke 23 ABC THE LOOK OF LOVE Karaoke 24 ACDC STIFF UPPER LIP Karaoke 25 ACE OF BASE ALL THAT SHE WANTS Karaoke 26 ACE OF BASE DONT TURN AROUND Karaoke 27 ACE OF BASE THE SIGN Karaoke 28 ADAM ANT ANT MUSIC Karaoke 29 AEROSMITH CRAZY Karaoke 30 AEROSMITH I DONT WANT TO MISS A THING Karaoke 31 AEROSMITH LOVE IN AN ELEVATOR Karaoke 32 AFROMAN BECAUSE I GOT HIGH Karaoke 33 AIR SUPPLY ALL OUT OF LOVE Karaoke 34 ALANIS MORISSETTE YOU OUGHTA KNOW Karaoke 35 ALANIS MORISSETTE THANK U Karaoke 36 ALANIS MORISSETTE ALL I REALLY WANT Karaoke 37 ALANIS MORISSETTE IRONIC Karaoke 38 ALANNAH MYLES BLACK VELVET Karaoke