Kenton Chambers and the Annual Species of Microseris

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Likely to Have Habitat Within Iras That ALLOW Road

Item 3a - Sensitive Species National Master List By Region and Species Group Not likely to have habitat within IRAs Not likely to have Federal Likely to have habitat that DO NOT ALLOW habitat within IRAs Candidate within IRAs that DO Likely to have habitat road (re)construction that ALLOW road Forest Service Species Under NOT ALLOW road within IRAs that ALLOW but could be (re)construction but Species Scientific Name Common Name Species Group Region ESA (re)construction? road (re)construction? affected? could be affected? Bufo boreas boreas Boreal Western Toad Amphibian 1 No Yes Yes No No Plethodon vandykei idahoensis Coeur D'Alene Salamander Amphibian 1 No Yes Yes No No Rana pipiens Northern Leopard Frog Amphibian 1 No Yes Yes No No Accipiter gentilis Northern Goshawk Bird 1 No Yes Yes No No Ammodramus bairdii Baird's Sparrow Bird 1 No No Yes No No Anthus spragueii Sprague's Pipit Bird 1 No No Yes No No Centrocercus urophasianus Sage Grouse Bird 1 No Yes Yes No No Cygnus buccinator Trumpeter Swan Bird 1 No Yes Yes No No Falco peregrinus anatum American Peregrine Falcon Bird 1 No Yes Yes No No Gavia immer Common Loon Bird 1 No Yes Yes No No Histrionicus histrionicus Harlequin Duck Bird 1 No Yes Yes No No Lanius ludovicianus Loggerhead Shrike Bird 1 No Yes Yes No No Oreortyx pictus Mountain Quail Bird 1 No Yes Yes No No Otus flammeolus Flammulated Owl Bird 1 No Yes Yes No No Picoides albolarvatus White-Headed Woodpecker Bird 1 No Yes Yes No No Picoides arcticus Black-Backed Woodpecker Bird 1 No Yes Yes No No Speotyto cunicularia Burrowing -

WRITTEN FINDINGS of the WASHINGTON STATE NOXIOUS WEED CONTROL BOARD 2018 Noxious Weed List Proposal

DRAFT: WRITTEN FINDINGS OF THE WASHINGTON STATE NOXIOUS WEED CONTROL BOARD 2018 Noxious Weed List Proposal Scientific Name: Tussilago farfara L. Synonyms: Cineraria farfara Bernh., Farfara radiata Gilib., Tussilago alpestris Hegetschw., Tussilago umbertina Borbás Common Name: European coltsfoot, coltsfoot, bullsfoot, coughwort, butterbur, horsehoof, foalswort, fieldhove, English tobacco, hallfoot Family: Asteraceae Legal Status: Proposed as a Class B noxious weed for 2018, to be designated for control throughout Washington, except for in Grant, Lincoln, Adams, Benton, and Franklin counties. Images: left, blooming flowerheads of Tussilago farfara, image by Caleb Slemmons, National Ecological Observatory Network, Bugwood.org; center, leaves of T. farfara growing with ferns, grasses and other groundcover species; right, mature seedheads of T. farfara before seeds have been dispersed, center and right images by Leslie J. Mehrhoff, University of Connecticut, Bugwood.org. Description and Variation: The common name of Tussilago farfara, coltsfoot, refers to the outline of the basal leaf being that of a colt’s footprint. Overall habit: Tussilago farfara is a rhizomatous perennial, growing up to 19.7 inches (50 cm tall), which can form extensive colonies. Plants first send up flowering stems in the spring, each with a single yellow flowerhead. Just before or after flowers have formed seeds, basal leaves on long petioles grow from the rhizomes, with somewhat roundish leaf blades that are more or less white-woolly on the undersides. Roots: Plants have long creeping, white scaly rhizomes (Griffiths 1994, Chen and Nordenstam 2011). Rhizomes are branching and have fibrous roots (Barkley 2006). They are also brittle and can break easily (Pfeiffer et al. -

A Biographical Index of British and Irish Botanists

L Biographical Index of British and Irish Botanists. TTTEN & BOULGER, A BIOaEAPHICAL INDEX OF BKITISH AND IRISH BOTANISTS. BIOGRAPHICAL INDEX OF BRITISH AND IRISH BOTANISTS COMPILED BY JAMES BEITTEN, F.L.S. SENIOR ASSISTANT, DEPARTMENT OF BOTANY, BBITISH MUSEUM AKD G. S. BOULGEE, E.L. S., F. G. S. PROFESSOR OF BOTANY, CITY OF LONDON COLLEGE LONDON WEST, NEWMAN & CO 54 HATTON GARDEN 1893 LONDON PRINTED BY WEST, NEWMAN AND HATTON GAEDEN PEEFACE. A FEW words of explanation as to the object and scope of this Index may fitly appear as an introduction to the work. It is intended mainly as a guide to further information, and not as a bibliography or biography. We have been liberal in including all who have in any way contributed to the literature of Botany, who have made scientific collections of plants, or have otherwise assisted directly in the progress of Botany, exclusive of pure Horticulture. We have not, as a rule, included those who were merely patrons of workers, or those known only as contributing small details to a local Flora. Where known, the name is followed by the years of birth and death, which, when uncertain, are marked with a ? or c. [circa) ; or merely approximate dates of "flourishing" are given. Then follows the place and day of bu'th and death, and the place of burial ; a brief indication of social position or occupation, espe- cially in the cases of artisan botanists and of professional collectors; chief university degrees, or other titles or offices held, and dates of election to the Linnean and Eoyal Societies. -

Inferences Based on ITS Molecular Phylogenetic Analyses

Korean J. Pl. Taxon. (2011) Vol. 41 No. 3, pp.209-214 The taxonomic status of Angelica purpuraefolia and its allies in Korea : Inferences based on ITS molecular phylogenetic analyses Byoung Yoon Lee1,2*, Myounghai Kwak1, Jeong Eun Han1,3 and Se-Jung Kim1,4 1Wildlife Genetic Resources Center, National Institute of Biological Resources, Incheon 404-170, Korea 2Division of Microorganism, National Institute of Biological Resources, Incheon 404-170, Korea 3Department of Biology, Inha University, Incheon 402-751, Korea 4Genome analyses center, National Instrumentation Center for Environmental Management, Seoul 151-921, Korea (Received 29 August 2011; Revised 08 September 2011; Accepted 13 September 2011) ABSTRACT: The taxonomy of the umbelliferous species Angelica amurensis and its allies was reviewed on the basis of molecular phylogenies derived from sequences of nuclear ribosomal DNA internal transcribed spacer (ITS) regions. Strict consensus of six minimal length 119-step trees derived from equally weighted maximum parsimony analysis of combined nuclear rDNA ITS1 and ITS2 sequences from 29 accessions of Angelica and outgroups indicated that Angelica purpuraefolia, known to be endemic to Korea, is the same species as A. amurensis. Comparisons of sequence pairs across both spacer regions revealed identity or 1-2 bp differences between A. purpuraefolia and A. amurensis. These results indicated that the two taxa are not distinguished taxonomically. Also, nuclear rDNA ITS regions are discussed as potential barcoding loci for identifying Korean Angelica. Keywords: Apiaceae, Angelica purpuraefolia, Angelica amurensis, DNA barcode The Korean endemic Angelica purpuraefolia Chung grows bioactivities have been protected by Korean patent law (Lee in mountainous areas in Gangwondo, Gyeongsangbugdo, and et al., 2005). -

Outline of Angiosperm Phylogeny

Outline of angiosperm phylogeny: orders, families, and representative genera with emphasis on Oregon native plants Priscilla Spears December 2013 The following listing gives an introduction to the phylogenetic classification of the flowering plants that has emerged in recent decades, and which is based on nucleic acid sequences as well as morphological and developmental data. This listing emphasizes temperate families of the Northern Hemisphere and is meant as an overview with examples of Oregon native plants. It includes many exotic genera that are grown in Oregon as ornamentals plus other plants of interest worldwide. The genera that are Oregon natives are printed in a blue font. Genera that are exotics are shown in black, however genera in blue may also contain non-native species. Names separated by a slash are alternatives or else the nomenclature is in flux. When several genera have the same common name, the names are separated by commas. The order of the family names is from the linear listing of families in the APG III report. For further information, see the references on the last page. Basal Angiosperms (ANITA grade) Amborellales Amborellaceae, sole family, the earliest branch of flowering plants, a shrub native to New Caledonia – Amborella Nymphaeales Hydatellaceae – aquatics from Australasia, previously classified as a grass Cabombaceae (water shield – Brasenia, fanwort – Cabomba) Nymphaeaceae (water lilies – Nymphaea; pond lilies – Nuphar) Austrobaileyales Schisandraceae (wild sarsaparilla, star vine – Schisandra; Japanese -

Redmond Watershed Preserve King County, Washington

Vascular Plant List: Redmond Watershed Preserve King County, Washington Partial list covers plants found in the 800-acre watershed managed by the city of Redmond primarily as a nature preserve. Habitats include shady 90-year old forest, sunny disturbed utility corridors, ephemeral drainages, perennial streams, ponds and other wetlands. The preserve has 7 miles of trails (see external links below), most of which are multi-use and a couple of which are ADA accessible. List originally compiled by Fred Weinmann in February 2002. Ron Bockelman made additions in 2018. 128 species (83 native, 45 introduced) Directions: 21760 NE Novelty Hill Rd, Redmond, WA 98052 is the physical address. Drive 2.3 miles east on Novelty Hill Rd from its junction with Avondale Rd. Turn left at the entrance across from 218 Ave NE and continue to the parking lot, information kiosk, and restrooms. Ownership: City of Redmond Access: Open during daylight hours. No pets allowed. Permits: None External Links: https://www.wta.org/go-hiking/hikes/redmond-watershed-preserve https://www.alltrails.com/parks/us/washington/redmond-watershed-preserve Coordinates: 47.695943°, -122.051161° Elevation: 300 - 700 feet Key to symbols: * = Introduced species. ? = Uncertain identification. + = Species is represented by two or more subspecies or varieties in Washington; the species in this list has not been identified to subspecies or variety. ! = Species is not known to occur near this location based on specimen records in the PNW Herbaria database, and may be misidentified. # = Species name could not be resolved to an accepted name; the name may be misspelled. Numeric superscripts after a scientific name indicates the name was more broadly circumscribed in the past, and has since been split into two or more accepted taxa in Washington. -

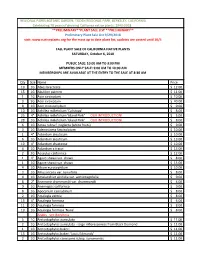

Qty Size Name Price 10 1G Abies Bracteata 12.00 $ 15 1G Abutilon

REGIONAL PARKS BOTANIC GARDEN, TILDEN REGIONAL PARK, BERKELEY, CALIFORNIA Celebrating 78 years of growing California native plants: 1940-2018 **PRELIMINARY**PLANT SALE LIST **PRELIMINARY** Preliminary Plant Sale List 9/29/2018 visit: www.nativeplants.org for the most up to date plant list, updates are posted until 10/5 FALL PLANT SALE OF CALIFORNIA NATIVE PLANTS SATURDAY, October 6, 2018 PUBLIC SALE: 10:00 AM TO 3:00 PM MEMBERS ONLY SALE: 9:00 AM TO 10:00 AM MEMBERSHIPS ARE AVAILABLE AT THE ENTRY TO THE SALE AT 8:30 AM Qty Size Name Price 10 1G Abies bracteata $ 12.00 15 1G Abutilon palmeri $ 11.00 1 1G Acer circinatum $ 10.00 3 5G Acer circinatum $ 40.00 8 1G Acer macrophyllum $ 9.00 10 1G Achillea millefolium 'Calistoga' $ 8.00 25 4" Achillea millefolium 'Island Pink' OUR INTRODUCTION! $ 5.00 28 1G Achillea millefolium 'Island Pink' OUR INTRODUCTION! $ 8.00 6 1G Actea rubra f. neglecta (white fruits) $ 9.00 3 1G Adenostoma fasciculatum $ 10.00 1 4" Adiantum aleuticum $ 10.00 6 1G Adiantum aleuticum $ 13.00 10 4" Adiantum shastense $ 10.00 4 1G Adiantum x tracyi $ 13.00 2 2G Aesculus californica $ 12.00 1 4" Agave shawii var. shawii $ 8.00 1 1G Agave shawii var. shawii $ 15.00 4 1G Allium eurotophilum $ 10.00 3 1G Alnus incana var. tenuifolia $ 8.00 4 1G Amelanchier alnifolia var. semiintegrifolia $ 9.00 8 2" Anemone drummondii var. drummondii $ 4.00 9 1G Anemopsis californica $ 9.00 8 1G Apocynum cannabinum $ 8.00 2 1G Aquilegia eximia $ 8.00 15 4" Aquilegia formosa $ 6.00 11 1G Aquilegia formosa $ 8.00 10 1G Aquilegia formosa 'Nana' $ 8.00 Arabis - see Boechera 5 1G Arctostaphylos auriculata $ 11.00 2 1G Arctostaphylos auriculata - large inflorescences from Black Diamond $ 11.00 1 1G Arctostaphylos bakeri $ 11.00 15 1G Arctostaphylos bakeri 'Louis Edmunds' $ 11.00 2 1G Arctostaphylos canescens subsp. -

Anaphalis Margaritacea (L) Benth

Growing and Using Native Plants in the Northern Interior of B.C. Anaphalis margaritacea (L) Benth. and Hook. F. ex C.B. Clarke pearly everlasting Family: Asteraceae Figure 79. Documented range of Anaphalis margaritacea in northern British Columbia. Figure 80. Growth habit of Anaphalis margaritacea in cultivation. Symbios Research & Restoration 2003 111 Growing and Using Native Plants in the Northern Interior of B.C. Anaphalis margaritacea pearly everlasting (continued) Background Information Anaphalis margaritacea can be found north to Alaska, the Yukon and Northwest Territories, east to Newfoundland and Nova Scotia, and south to North Carolina, Kentucky, Arizona, New Mexico and California. It is reported to be common throughout B.C. except in the northeast (Douglas et al. 1998). Growth Form: Rhizomatous perennial herb, with few basal leaves, alternate stem leaves light green above, woolly white underneath; flower heads in dense flat-topped clusters, yellowish disk flowers; involucral bracts dry pearly white; mature plant size is 20-90 cm tall (MacKinnon et al. 1992, Douglas 1998). Site Preferences: Moist to dry meadows, rocky slopes, open forest, landings, roadsides and other disturbed sites from low to subalpine elevations, throughout most of B.C. In coastal B.C., it is reported to be shade-intolerant and occupies exposed mineral soil on disturbed sites and water- shedding sites up to the alpine (Klinka et al. 1989). Seed Information Seed Size: Length: 0.97 mm (0.85 - 1.07 mm). Width : 0.32 mm (0.24 - 0.37 mm). Seeds per gram: 24,254 (range: 13,375 - 37,167). Volume to Weight Conversion: 374.0 g/L at 66.7.5% purity. -

Molecular Phylogeny of Chinese Thuidiaceae with Emphasis on Thuidium and Pelekium

Molecular Phylogeny of Chinese Thuidiaceae with emphasis on Thuidium and Pelekium QI-YING, CAI1, 2, BI-CAI, GUAN2, GANG, GE2, YAN-MING, FANG 1 1 College of Biology and the Environment, Nanjing Forestry University, Nanjing 210037, China. 2 College of Life Science, Nanchang University, 330031 Nanchang, China. E-mail: [email protected] Abstract We present molecular phylogenetic investigation of Thuidiaceae, especially on Thudium and Pelekium. Three chloroplast sequences (trnL-F, rps4, and atpB-rbcL) and one nuclear sequence (ITS) were analyzed. Data partitions were analyzed separately and in combination by employing MP (maximum parsimony) and Bayesian methods. The influence of data conflict in combined analyses was further explored by two methods: the incongruence length difference (ILD) test and the partition addition bootstrap alteration approach (PABA). Based on the results, ITS 1& 2 had crucial effect in phylogenetic reconstruction in this study, and more chloroplast sequences should be combinated into the analyses since their stability for reconstructing within genus of pleurocarpous mosses. We supported that Helodiaceae including Actinothuidium, Bryochenea, and Helodium still attributed to Thuidiaceae, and the monophyletic Thuidiaceae s. lat. should also include several genera (or species) from Leskeaceae such as Haplocladium and Leskea. In the Thuidiaceae, Thuidium and Pelekium were resolved as two monophyletic groups separately. The results from molecular phylogeny were supported by the crucial morphological characters in Thuidiaceae s. lat., Thuidium and Pelekium. Key words: Thuidiaceae, Thuidium, Pelekium, molecular phylogeny, cpDNA, ITS, PABA approach Introduction Pleurocarpous mosses consist of around 5000 species that are defined by the presence of lateral perichaetia along the gametophyte stems. Monophyletic pleurocarpous mosses were resolved as three orders: Ptychomniales, Hypnales, and Hookeriales (Shaw et al. -

TAXONOMY Plant Family Species Scientific Name Angelica Genuflexa

Plant Propagation Protocol for Angelica genuflexa ESRM 412 – Native Plant Production Protocol URL: https://courses.washington.edu/esrm412/protocols/ANGE2.pdf North American Distribution1 Washington Distribution2 TAXONOMY Plant Family Scientific Name Apiaceae / Umbelliferae Common Name Carrot Family Species Scientific Name Scientific Name Angelica genuflexa Nutt. Varieties N/A Sub-species N/A Cultivar N/A Common Synonym(s) N/A Common Name(s) Kneeling Angelica Species Code (as per USDA Plants ANGE2 database) GENERAL INFORMATION Geographical range Found West of the Cascades in Washington, in Alaska to down South in California. Also found in West Canada3. Maps are also above. Ecological distribution Found in wet ecosystems: meadows, coasts, stream banks, and wetlands2. Climate and elevation range Grows in mid to low elevations3 Local habitat and abundance Associated with Mountain hemlock, Pacific silver fir, and Western hemlock forests7. Grows moist areas: swamps, stream banks, and flooded or ponded marshes7. Plant strategy type / successional Is moderately shade tolerant, can thrive in stable stage communities7. Plant characteristics A stout perennial herb. Grows 1-1.5 meters tall4. Features a hollow, that is often purple and shiny stem2. Stalk is bent, giving its name. Grows from a tap root5. Leaves are pinnately compound, with the first pair of leaflets being bent back at stem. Leaflets are ovate to lanceolate, coarsely toothed, and 1-4 inches long2. Flowers are clustered, contains up to 50 rays, each ray containing its own smaller cluster of white or pink flowers5. PROPAGATION DETAILS Ecotype N/A Propagation Goal Seeds Propagation Method Seeds Product Type Seeds Stock Type N/A Time to Grow Late summer to winter. -

Field Release of the Hoverfly Cheilosia Urbana (Diptera: Syrphidae)

USDA iiillllllllll United States Department of Field release of the hoverfly Agriculture Cheilosia urbana (Diptera: Marketing and Regulatory Syrphidae) for biological Programs control of invasive Pilosella species hawkweeds (Asteraceae) in the contiguous United States. Environmental Assessment, July 2019 Field release of the hoverfly Cheilosia urbana (Diptera: Syrphidae) for biological control of invasive Pilosella species hawkweeds (Asteraceae) in the contiguous United States. Environmental Assessment, July 2019 Agency Contact: Colin D. Stewart, Assistant Director Pests, Pathogens, and Biocontrol Permits Plant Protection and Quarantine Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service U.S. Department of Agriculture 4700 River Rd., Unit 133 Riverdale, MD 20737 Non-Discrimination Policy The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination against its customers, employees, and applicants for employment on the bases of race, color, national origin, age, disability, sex, gender identity, religion, reprisal, and where applicable, political beliefs, marital status, familial or parental status, sexual orientation, or all or part of an individual's income is derived from any public assistance program, or protected genetic information in employment or in any program or activity conducted or funded by the Department. (Not all prohibited bases will apply to all programs and/or employment activities.) To File an Employment Complaint If you wish to file an employment complaint, you must contact your agency's EEO Counselor (PDF) within 45 days of the date of the alleged discriminatory act, event, or in the case of a personnel action. Additional information can be found online at http://www.ascr.usda.gov/complaint_filing_file.html. To File a Program Complaint If you wish to file a Civil Rights program complaint of discrimination, complete the USDA Program Discrimination Complaint Form (PDF), found online at http://www.ascr.usda.gov/complaint_filing_cust.html, or at any USDA office, or call (866) 632-9992 to request the form. -

<I>Sphagnum</I> Peat Mosses

ORIGINAL ARTICLE doi:10.1111/evo.12547 Evolution of niche preference in Sphagnum peat mosses Matthew G. Johnson,1,2,3 Gustaf Granath,4,5,6 Teemu Tahvanainen, 7 Remy Pouliot,8 Hans K. Stenøien,9 Line Rochefort,8 Hakan˚ Rydin,4 and A. Jonathan Shaw1 1Department of Biology, Duke University, Durham, North Carolina 27708 2Current Address: Chicago Botanic Garden, 1000 Lake Cook Road Glencoe, Illinois 60022 3E-mail: [email protected] 4Department of Plant Ecology and Evolution, Evolutionary Biology Centre, Uppsala University, Norbyvagen¨ 18D, SE-752 36, Uppsala, Sweden 5School of Geography and Earth Sciences, McMaster University, Hamilton, Ontario, Canada 6Department of Aquatic Sciences and Assessment, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, SE-750 07, Uppsala, Sweden 7Department of Biology, University of Eastern Finland, P.O. Box 111, 80101, Joensuu, Finland 8Department of Plant Sciences and Northern Research Center (CEN), Laval University Quebec, Canada 9Department of Natural History, Norwegian University of Science and Technology University Museum, Trondheim, Norway Received March 26, 2014 Accepted September 23, 2014 Peat mosses (Sphagnum)areecosystemengineers—speciesinborealpeatlandssimultaneouslycreateandinhabitnarrowhabitat preferences along two microhabitat gradients: an ionic gradient and a hydrological hummock–hollow gradient. In this article, we demonstrate the connections between microhabitat preference and phylogeny in Sphagnum.Usingadatasetof39speciesof Sphagnum,withan18-locusDNAalignmentandanecologicaldatasetencompassingthreelargepublishedstudies,wetested