Musqueam Weavers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Owner 1 Owner 2 Property Description Parcel Id# Pin

OWNER 1 OWNER 2 PROPERTY DESCRIPTION PARCEL ID# PIN# BILL NUMBER TAX LEVY COSTS ANDTOTAL FEES DUE SITUS ADDRESS 210 HIGHWAY DEVELOPMENT LLC 0.073AC GWEN OAKS SD MAP#2012-596 010547 0024 68 0536-02-3376.000 0002177173-2018-2018-000000 $ 3.05 $ - $ 5.00 $ 8.05 HONOR OFF LN UNINCORPORATED 210 HIGHWAY DEVELOPMENT LLC OPEN SPC GWEN OAKS 0.366AC MAP#2009-667 010547 0024 49 0536-02-7628.000 0001427310-2018-2018-000000 $ 69.60 $ - $ 5.00 $ 74.60 23 HONOR LN BUNNLEVEL NC 28323 256 KIT STEWARD LN TRUST MNGMT SRVICES LLC TRUSTEE LT#7 KIT STEWART 0.30AC 080653 0001 0653-69-8530.000 0000035234-2018-2018-000000 $ 344.21 $ - $ 5.00 $ 349.21 256 KIT STEWART LN FUQUAY VARINA NC 27526 26 BOND STREET MANAGEMENT LLC 1 LT COL A JOHNSON 75X150LT#5 MB#10/1 021515 0225 1515-49-8767.000 0000043537-2018-2018-000000 $ 1,414.91 $ - $ 5.00 $ 1,419.91 204 AMMONS RD DUNN NC 28334 301 SERVICE CENTER AND SALES LLC 0.15AC CLINTON AVE 02151611220036 01 1516-43-9637.000 0000014516-2018-2018-000000 $ 24.48 $ - $ 5.00 $ 29.48 S CLINTON OFF AVE UNINCORPORATED ABDUSSAMADI, ELVIA MCRAE 1 LT 109 E GRANVILLE 100X135 021517200600 02 1516-89-3916.000 0000015246-2018-2018-000000 $ 852.95 $ - $ 5.00 $ 857.95 109 E GRANVILLE ST DUNN NC 28334 ADAMS, CHARLES GLENWOOD JR ADAMS, BRENDA SMITH .54 ACRES B F DUPREE 070693 0016 0693-95-8642.000 0000000176-2018-2018-000000 $ 434.66 $ - $ 5.00 $ 439.66 4269 PINEY GROVE RD ANGIER NC 27501 ADAMS, CONRAD L II ADAMS, GAIL M LT#37M BLK#7 CPTN LANDINGMB#21/52 050613 0097 0613-63-4584.000 0000000188-2018-2018-000000 $ 24.90 $ - $ 5.00 $ 29.90 MARKET -

February 26, 2021 Amazon Warehouse Workers In

February 26, 2021 Amazon warehouse workers in Bessemer, Alabama are voting to form a union with the Retail, Wholesale and Department Store Union (RWDSU). We are the writers of feature films and television series. All of our work is done under union contracts whether it appears on Amazon Prime, a different streaming service, or a television network. Unions protect workers with essential rights and benefits. Most importantly, a union gives employees a seat at the table to negotiate fair pay, scheduling and more workplace policies. Deadline Amazon accepts unions for entertainment workers, and we believe warehouse workers deserve the same respect in the workplace. We strongly urge all Amazon warehouse workers in Bessemer to VOTE UNION YES. In solidarity and support, Megan Abbott (DARE ME) Chris Abbott (LITTLE HOUSE ON THE PRAIRIE; CAGNEY AND LACEY; MAGNUM, PI; HIGH SIERRA SEARCH AND RESCUE; DR. QUINN, MEDICINE WOMAN; LEGACY; DIAGNOSIS, MURDER; BOLD AND THE BEAUTIFUL; YOUNG AND THE RESTLESS) Melanie Abdoun (BLACK MOVIE AWARDS; BET ABFF HONORS) John Aboud (HOME ECONOMICS; CLOSE ENOUGH; A FUTILE AND STUPID GESTURE; CHILDRENS HOSPITAL; PENGUINS OF MADAGASCAR; LEVERAGE) Jay Abramowitz (FULL HOUSE; GROWING PAINS; THE HOGAN FAMILY; THE PARKERS) David Abramowitz (HIGHLANDER; MACGYVER; CAGNEY AND LACEY; BUCK JAMES; JAKE AND THE FAT MAN; SPENSER FOR HIRE) Gayle Abrams (FRASIER; GILMORE GIRLS) 1 of 72 Jessica Abrams (WATCH OVER ME; PROFILER; KNOCKING ON DOORS) Kristen Acimovic (THE OPPOSITION WITH JORDAN KLEPPER) Nick Adams (NEW GIRL; BOJACK HORSEMAN; -

Artists and Yamaha

Artists and Yamaha CONTENTS Turning The Artist’s Imagination INTRO CONTENTS 1 ELECTRIC BASSES OTHERS YAMAHA GUITAR DEVELOPMENT 3 RBX4A2/4A2M/5A2 22 GIGMAKER 39 YASH (YAMAHA ARTIST SERVICES HOLLYWOOD) 3 BB INTRO 23 ACCESSORIES/AMP 40 YMC (YAMAHA MUSIC CRAFT) 4 Into Tomorrow’s Music. BB2024/2024X/2025/2025X 25 YAMAHA ARTISTS 41 ELECTRIC GUITARS BB1024/1024X/1025/1025X 27 For over 60 years, we’ve been committed to improving the quality, sound, playability, durability, and design of our instruments. Feedback SG INTRO 5 BB424/424X/425/425X 29 from our valued customers and the professional musicians that use our instruments has always played an instrumental role in our passion SG FEATURES 7 ATTITUDE LTD3 31 for constant improvement. Because we believe that instruments are the tools musicians use to create music, our strive to create the ideal SG1820 9 BB714BS 32 instrument for the player is never ending. SG1820A/1802 11 BBNE2 33 Professional musicians are the most critical when it comes to requests and requirements, and we focus a great deal of time and effort bringing CV820WB 13 TRBJPII 34 their ideas to life. Our purpose is to turn what exists only in their imagination, into something they can hold and use in their hands—fi nding PAC1511MS 14 TRB1006J/1005L/1004J 35 the right type of tone, the perfect attack, or a neck that fi ts better in the hand. PAC212VFM/VQM/112V 15 RBX374/375/270J/170 37 The evolution of Yamaha guitars has always been closely related to our long-standing relationships with the musicians that use them. -

The SAA Archaeological Record (ISSN 1532-7299) Is Published five Times a Year Andrew Duff and Is Edited by Andrew Duff

the archaeologicalrecord SAA SEPTEMBER 2007 • VOLUME 7 • NUMBER 4 SOCIETY FOR AMERICAN ARCHAEOLOGY the SAAarchaeologicalrecord The Magazine of the Society for American Archaeology Volume 7, No. 4 September 2007 Editor’s Corner 2 Andrew Duff Letters to the Editor 3 From the President 6 Dean R. Snow In Brief 7 Tobi A. Brimsek Archaeopolitics 8 Dan Sandweiss and David Lindsay Probing during cemetery Vancouver in 2008 9 Dana Lepofsky, Sue Rowley, delineation in Coweta Andrew Martindale, County, Georgia. and Alan McMillan Photo by Ron Hobgood. RPA: The Issue of Commercialism: Proposed Changes 10 Jeffrey H. Altschul to the Register’s Code of Conduct Archaeology’s High Society Blues: Reply to McGimsey 11 Lawrence E. Moore Amerind-SAA Seminars: A Progress Report 15 John A. Ware Email X and the Quito Airport Archaeology 20 Douglas C. Comer Controversy: A Cautionary Tale for Scholars in the Age of Rapid Information Flow Identifying the Geographic Locations 24 German Loffler in Need of More CRM Training Can the Dissertation Be All Things to All People? 29 John D. Rissetto Networks: Historic Preservation Learning Portal: 33 Richard C. Waldbauer, Constance Werner Ramirez, A Performance Support Project for and Dan Buan Cultural Resource Managers Interfaces: 12V 35 Harold L. Dibble, Shannon J.P. McPherron, and Thomas McPherron Heritage Planning 42 Yun Shun Susie Chung In Memoriam: Jaime Litvak King 47 Emily McClung de Tapia and Paul Schmidt Calls for Awards Nominations 48 positions open 52 news and notes 54 calendar 56 EDITOR’S CORNER the SAAarchaeologicalrecord The Magazine of the Society for American Archaeology Volume 7, No. -

Aboriginal Participation in the 2010 Olympic Games Planning Process

RIGHTS, RITUALS, AND REPERCUSSIONS: ABORIGINAL PARTICIPATION IN THE 2010 OLYMPIC GAMES PLANNING PROCESS by Priya Vadi BSc (Honours), University of the West of England, 2006 THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS In the Department of Geography © Priya Vadi 2010 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Fall 2010 All rights reserved. However, in accordance with the Copyright Act of Canada, this work may be reproduced, without authorization, under the conditions for Fair Dealing. Therefore, limited reproduction of this work for the purposes of private study, research, criticism, review and news reporting is likely to be in accordance with the law, particularly if cited appropriately. APPROVAL Name: Priya Vadi Degree: Master of Arts Title of Thesis: Rights, Rituals, and Repercussions: Aboriginal Participation in the 2010 Olympic Games Planning Process Examining Committee: Chair: ________________________________________ Dr. Paul Kingsbury Assistant Professor, Department of Geography ________________________________________ Dr. Meg Holden Senior Supervisor Associate Professor, Urban Studies Program and Department of Geography ________________________________________ Dr. Geoff Mann Supervisor Associate Professor, Department of Geography ________________________________________ Dr. Peter Williams External Examiner Professor, School of Resource and Environmental Management Date Defended/Approved: October 5 2010 ii Declaration of Partial Copyright Licence The author, whose copyright is declared on the title page of this work, has granted to Simon Fraser University the right to lend this thesis, project or extended essay to users of the Simon Fraser University Library, and to make partial or single copies only for such users or in response to a request from the library of any other university, or other educational institution, on its own behalf or for one of its users. -

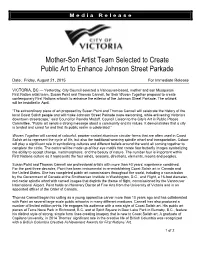

M E D I a R E L E A

M e d i a R e l e a s e Mother-Son Artist Team Selected to Create Public Art to Enhance Johnson Street Parkade Date: Friday, August 21, 2015 For Immediate Release VICTORIA, BC — Yesterday, City Council selected a Vancouver-based, mother and son Musqueam First Nation artist team, Susan Point and Thomas Cannell, for their Woven Together proposal to create contemporary First Nations artwork to enhance the exterior of the Johnson Street Parkade. The artwork will be installed in April. “The extraordinary piece of art proposed by Susan Point and Thomas Cannell will celebrate the history of the local Coast Salish people and will make Johnson Street Parkade more welcoming, while enlivening Victoria’s downtown streetscape,” said Councillor Pamela Madoff, Council Liaison to the City’s Art in Public Places Committee. “Public art sends a strong message about a community and its values. It demonstrates that a city is tended and cared for and that its public realm is celebrated.” Woven Together will consist of colourful, powder-coated aluminum circular forms that are often used in Coast Salish art to represent the cycle of life, but also the traditional weaving spindle whorl and transportation. Colour will play a significant role in symbolizing cultures and different beliefs around the world all coming together to complete the circle. The centre will be made up of four eye motifs that create four butterfly images symbolizing the ability to accept change, metamorphosis, and the beauty of nature. The number four is important within First Nations culture as it represents the four winds, seasons, directions, elements, moons and peoples. -

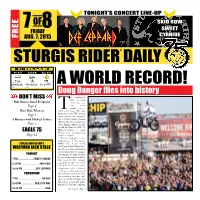

A World Record!

TONight’s CONCERT LINE-UP OF SKID ROW EE 7 8 SWEET FRIDAY CYANIDE FR AUG. 7, 2015 ® STURGIS RIDER DAILY Fri 8/7 Sat 8/8 Sun 8/9 A WORLD RecORD! Doug Danger flies into history he undisputed DON’t Miss king of stunt Bob Hansen Award Recipients men? Sure, cer- Page 4 tain names might come to Rat’s Hole Winners mind at that phrase. But since Tyesterday, at 6:03 PM, the only Page 5 name people are mention- 5 Minutes with Michael Lichter ing is Doug Danger. Because that was the time on the clock Page 3 when Danger jumped 22 cars aboard Evel Knievel’s XR-750 Harley-Davidson, a stunt EAGLE 75 Knievel once attempted but Page 12 failed to complete. The feat took place in the amphitheater at the Sturgis STURGIS BUFFALo Chip’s Buffalo Chip as part of the Evel Knievel Thrill Show. Dan- WOLFMAN JACK STAGE ger, who has been performing motorcycle jumps for decades, TONIGHT was inspired by Knievel when he was young and got to know 7 PM ..................SWEET CYANIDE him later in life. Danger 8:30 PM .....................SKID ROW regarded this stunt not as way to best his hero but as a favor, 10:30 PM ...............DEF LEPPARD completing a task for a friend. Danger is fully cognizant of TOMORROW the potential peril of his cho- sen profession and he’s real- 7 PM ............................ NICNOS istic; he knows firsthand the flip side of a successful jump. 8:30 PM ............... ADELITAS WAY But he felt solid and confident 10:30 PM ..........................WAR Continued on Page 2 PAGE 2 STURGIS RIDER DAILY FRIDAY, AUG. -

The United Methodist Church (¶¶347.1, 416.5, 635.2N)? (List Alphabetically

1 Revised February 2020 (final v for 2020) PART II PERTAINING TO ORDAINED AND LICENSED CLERGY (Note: A (v) notation following a question in this section signifies that the action or election requires a majority vote of the clergy session of the annual conference. If an action requires more than a simple majority, the notation (v 2/3) or (v 3/4) signifies that a two-thirds or three-fourths majority vote is required. Indicate credential of persons in Part II: FD, FE, PD, PE, and AM when requested.) 17. Are all the clergy members of the conference blameless in their life and official administration (¶¶604.4, 605.7)? Are all the clergy members of the conference blameless in their life and official administration (604.4, 605.7)? Yes, to the best of our knowledge, except for those who are involved in supervisory correction and/or Judicial or Administrative complaint processes. We, the bishop, conference lay leader, and cabinet members, take very seriously the call to moral excellence in the lives of pastors and conference leaders. We offer our signatures in answer to this question, knowing that only by the grace of God can any of us be blameless in our life and official administration. Lisa Neslony 18. Who constitute: a) The Administrative Review Committee (¶636)? (v) Clergy in Full Connection: Phyllis Barren, Quinton Gibson, Sr., Howard Martin Alternate Clergy in Full Connection: Jim Conner, Tomeca Richardson b) The Conference Relations Committee of the Board of Ordained Ministry (¶635.1d)? Steven Bell, Beverly Connelly, Beth Evers, Wade Killough, Jeff Miller, Sandra Oliver, Daniel So, Amy Tate-Almy, Carol Woods 2 Revised February 2020 (final v for 2020) c) The Committee on Investigation (¶2703) Clergy in Full Connection: Chris Mesa, Chauncey Nealy, Kissa Vaughn Alternate Clergy in Full Connection: Carol Gibson, Matt Hall, Stephanie “Evie” McKellar Professing Members: Lynn Gray, Steve McIver, Cheryl Wilson Alternate Professing Members: Kay Alston, Jody Bergman, Vivian Campbell, Sherry Doty, Dawn Gilliland 19. -

Coast Salish Textiles: from ‘Stilled Fingers’ to Spinning an Identity

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings Textile Society of America 2010 Coast Salish Textiles: From ‘Stilled Fingers’ to Spinning an Identity Eileen Wheeler Kwantlen Polytechnic University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf Part of the Art and Design Commons Wheeler, Eileen, "Coast Salish Textiles: From ‘Stilled Fingers’ to Spinning an Identity" (2010). Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings. 59. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf/59 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Textile Society of America at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. NOMINATED FOR FOUNDING PRESIDENTS AWARD COAST SALISH TEXTILES: FROM STILLED FINGERS TO SPINNING AN IDENTITY EILEEN WHEELER [email protected] Much that had been theirs that was fine was destroyed and lost. Much that they were proud of still remains, but goes unnoticed by those who have not the eyes to see nor the desire to comprehend.1 ~ Oliver Wells, 1965 I feel free when I weave. ~ Frieda George, 2010 When aboriginal women of south western British Columbia, Canada undertook to revisit their once prolific and esteemed ancestral textile practices, the strand of cultural knowledge linking this heritage to contemporary life had become extremely tenuous. It is through an engagement with cultural memory, painstakingly reclaimed, that Coast Salish women began a revival in the 1960s. It included historically resonant weaving and basketry, as well as the more recent adaptive and expedient practice of knitting. -

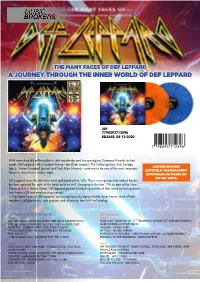

A Journey Through the Inner World of Def Leppard

THE MANY FACES OF DEF LEPPARD A JOURNEY THROUGH THE INNER WORLD OF DEF LEPPARD 2LP 7798093712896 RELEASE: 04-12-2020 With more than 65 million albums sold worldwide and two prestigious Diamond Awards to their credit, Def Leppard with its current line-up –Joe Elliott (vocals), Phil Collen (guitar), Rick Savage LIMITED EDITION (bass), Vivian Campbell (guitar) and Rick Allen (drums)— continue to be one of the most important GATEFOLD TRANSPARENT forces in rock music.n many ways, ORANGE/BLUE MARBLED 180 GR. VINYL Def Leppard were the definitive hard rock band of the ‘80s. There were groups that rocked harder, but few captured the spirit of the times quite as well. Emerging in the late ‘70s as part of the New Wave of British Heavy Metal, Def Leppard gained a following outside of that scene by toning down their heavy riffs and emphasizing melody. In The Many Faces of Def Leppard, we are going to dig deep into the lesser known work of their members, collaborations, side projects and of course, their hit-filled catalog. LP1 - THE MANY FACES OF DEF LEPPARD LP2 - THE SONGS Side A Side A ALL JOIN HANDS - ROADHOUSE FEAT. PETE WILLIS & FRANK NOON POUR SOME SUGAR ON ME - LEE THOMPSON, JOHNNY DEE, RICHARD KENDRICK, I WILL BE THERE - GOMAGOG FEAT. PETE WILLIS & JANICK GERS MARKO PUKKILA & HOWIE SIMON DOIN’ FINE - CARMINE APPICE FEAT. VIVIAN CAMPBELL HYSTERIA - DANIEL FLORES ON A LONELY ROAD - THE FROG & THE RICK VITO BAND LET IT GO - WICKED GARDEN FEAT. JOE ELLIOTT ROCK ROCK TIL YOU DROP - CHRIS POLAND, JOE VIERS & RICHARD KENDRICK OVER MY DEAD BODY - MAN RAZE FEAT. -

Pacific Coast Salish Art and Artists: Educator Resource Guide

S’abadeb— TheGifts: PacificCoast SalishArt &Artists SEATTLE ART MUSEUM EDUCATOR RESOURCE GUIDE Grades3-12 SeattleArtMuseum S’abadeb—The Gifts: Pacific Coast Salish Art and Artists 1300 First Avenue is organized by the Seattle Art Museum and made Seattle, WA 98101 206.654.3100 possible by a generous leadership grant from The Henry seattleartmuseum.org Luce Foundation and presenting sponsors the National Endowment for the Humanities and The Boeing Company. © 2008 Seattle Art Museum This project is supported in part by an award from the National Endowment for the Arts with major support Pleasedirectquestionsabout thisresourceguideto: provided by the Mayor’s Office of Arts & Cultural Affairs, Adobe Systems, Incorporated, PONCHO, Washington State School & Educator Programs Arts Commission, and U.S. Bancorp Foundation. Additional Seattle Art Museum, 206.654.3146 [email protected] support provided by the Native Arts of the Americas and Oceania Council at the Seattle Art Museum, Thaw Exhibitionitinerary: Charitable Trust, Charlie and Gayle Pancerzewski, Suquamish Seattle Art Museum Clearwater Casino Resort, The Hugh and Jane Ferguson October 24, 2008–January 11, 2009 Foundation, Humanities Washington, Kreielsheimer Exhibition Endowment and contributors to the Annual Fund. Royal British Columbia Museum November 20–March 8, 2010 Art education programs and resources supported in Editing: John Pierce part by PONCHO and the Harrington-Schiff Foundation. Author: Nan McNutt Illustrations: Greg Watson ProjectManager: -

First Nations Public Art to Be Installed This Week at Johnson Street Parkade

M e d i a R e l e a s e First Nations Public Art to be Installed This Week at Johnson Street Parkade Date: Wednesday, August 24, 2016 For Immediate Release VICTORIA, BC — Public art will soon enhance the exterior of the Johnson Street Parkade and the downtown streetscape. Work is underway to install Woven Together , the contemporary First Nations artwork by Vancouver-based mother and son Musqueam artist team Susan Point and Thomas Cannell. Woven Together consists of colourful, powder-coated aluminum circular forms that are often used in Coast Salish art to represent the cycle of life, but also the traditional weaving spindle whorl and transportation. Colour plays a significant role in symbolizing cultures and different beliefs around the world all coming together to complete the circle. The centre is made up of four eye motifs that create four butterfly images symbolizing the ability to accept change, metamorphosis, and the beauty of nature. The number four is important within First Nations culture as it represents the four winds, seasons, directions, elements, moons and peoples. Approximately six metres wide by eight metres high, Woven Together contains 82 pieces which will be mounted to the building’s façade. A template will be used to mark and pre-drill holes in which to secure each art piece. The Johnson Street Parkade will remain open during the artwork’s installation but parking customers may experience minor delays entering the parkade. The work will take place daily this week from 9 a.m. – 8 p.m. and is anticipated to be completed by Friday.