Economic Review 99-03

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

National Income in India, Concept and Measurement

National Income in India, Concept and Measurement National Income :- • National income is the money value of all the final goods and services produced by a country during a period of one year. National income consists of a collection of different types of goods and services of different types. • Since these goods are measured in different physical units it is not possible to add them together. Thus we cannot state national income is so many millions of meters of cloth. Therefore, there is no way except to reduce them to a common measure. This common measure is money. Basic Concepts in National Income:- • Gross domestic product • Gross domestic product at constant price and at current price • Gross domestic product at factor cost and Gross domestic product at market price • Net domestic product • Gross national product • Net national Product • Net national product at factor cost or national income Gross Domestic Product • Gross domestic product is the money value of all final goods and services produced in the domestic territory of a country during an accounting year. Gross Domestic Product at Constant price and Current price • GDP can be estimated at current prices and at constant prices. If the domestic product is estimated on the basis of the prevailing prices it is called gross domestic product at current prices. • If GDP is measured on the basis of some fixed price, that is price prevailing at a point of time or in some base year it is known as GDP at constant price or real gross domestic product. GDP at Factor cost and GDP at Market price • The contribution of each producing unit to the current flow of goods and services is known as the net value added. -

The Yen and the Japanese Economy, 2004

8 The Yen and the Japanese Economy, 2004 TAKATOSHI ITO This chapter presents an overview of the Japanese macroeconomy and its exchange rate policy and monetary policy in the period 2003–04. It also examines the effects of the exchange rate changes on Japanese trade bal- ances. The monetary authorities of Japan—namely, the Ministry of Finance and the Bank of Japan (MOF-BOJ)—intervened in the foreign exchange market frequently heavily in 2003–04. The authorities sold ¥35 trillion (or $320 billion), 7 percent of the Japanese GDP, between January 2003 and March 2004. This chapter examines the presumed objectives of the large interventions and their effectiveness. Why the Japanese authorities inter- vened to this unprecedented extent is explained here in the context of the macroeconomic conditions and developments in the foreign exchange, spot, and futures markets. To summarize the chapter’s conclusions, interventions were conducted for several reasons—including to prevent “premature” appreciation in the midst of a weak economy, to help monetary policy by providing opportu- nities for unsterilized interventions, and to defuse excessive speculative pressure. These hypotheses on the motivations for intervention are sup- ported by data, but it is more difficult to judge whether the intended effects of the MOF-BOJ’s actions were achieved. Japan’s macroeconomic conditions are described in the chapter’s second section. The third section examines the relationship between the exchange rate and net exports of Japan. The next sections explains the reasons for heavy interventions from January 2003 to March 2004 and section provide data to back up these explanations. -

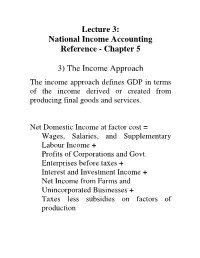

Lecture 3: National Income Accounting Reference - Chapter 5

Lecture 3: National Income Accounting Reference - Chapter 5 3) The Income Approach The income approach defines GDP in terms of the income derived or created from producing final goods and services. Net Domestic Income at factor cost = Wages, Salaries, and Supplementary Labour Income + Profits of Corporations and Govt. Enterprises before taxes + Interest and Investment Income + Net Income from Farms and Unincorporated Businesses + Taxes less subsidies on factors of production Net Domestic Income at market prices = Net Domestic Income at factor cost + Indirect taxes less subsidies Gross Domestic Product (GDP) at market prices = Net Domestic Income at market prices + Capital Consumption Allowances + Statistical Discrepancy OTHER NATIONAL ACCOUNTS Gross National Product (GNP) = Gross Domestic Product (GDP) + Net Investment from Non-residents = 1154.9 – 84.9 = 1070 Example – The production of cars in the Honda factory in Alliston, Ontario is included in both Canadian GDP and GNP. But GNP excludes profit sent to foreign shareholders of Honda, but this profit is included in Canadian GDP. Net Domestic Product (NDP) = GNP – Depreciation = 1070–155 = 915 Net National Income at Basic Prices (NNI) = NDP- Taxes less subsidies on factors of production - Indirect taxes less subsidies = 915 – 53.8 – 84.4 = 776.8 Personal Income = NNI – Undistributed Corporate Profits + Govt. Transfer Payments = 776.8 – 49.0 +71.3 = 848.1 Disposable Income = PI – Personal Taxes = 848 – 152.2 = 695.9 Nominal GDP Versus Real GDP Nominal GDP is the GDP measured in terms of the price level at the time of measurement (unadjusted for inflation). Problem: How can we compare the market values of GDP from year to year if the value of money itself changes because of inflation or deflation? - Compare 5% increase in Q with no change in P and 5% increase in P with no change in Q - The way around this problem is to deflate GDP when prices rise and to inflate GDP when prices fall. -

GDP As a Measure of Economic Well-Being

Hutchins Center Working Paper #43 August 2018 GDP as a Measure of Economic Well-being Karen Dynan Harvard University Peterson Institute for International Economics Louise Sheiner Hutchins Center on Fiscal and Monetary Policy, The Brookings Institution The authors thank Katharine Abraham, Ana Aizcorbe, Martin Baily, Barry Bosworth, David Byrne, Richard Cooper, Carol Corrado, Diane Coyle, Abe Dunn, Marty Feldstein, Martin Fleming, Ted Gayer, Greg Ip, Billy Jack, Ben Jones, Chad Jones, Dale Jorgenson, Greg Mankiw, Dylan Rassier, Marshall Reinsdorf, Matthew Shapiro, Dan Sichel, Jim Stock, Hal Varian, David Wessel, Cliff Winston, and participants at the Hutchins Center authors’ conference for helpful comments and discussion. They are grateful to Sage Belz, Michael Ng, and Finn Schuele for excellent research assistance. The authors did not receive financial support from any firm or person with a financial or political interest in this article. Neither is currently an officer, director, or board member of any organization with an interest in this article. ________________________________________________________________________ THIS PAPER IS ONLINE AT https://www.brookings.edu/research/gdp-as-a- measure-of-economic-well-being ABSTRACT The sense that recent technological advances have yielded considerable benefits for everyday life, as well as disappointment over measured productivity and output growth in recent years, have spurred widespread concerns about whether our statistical systems are capturing these improvements (see, for example, Feldstein, 2017). While concerns about measurement are not at all new to the statistical community, more people are now entering the discussion and more economists are looking to do research that can help support the statistical agencies. While this new attention is welcome, economists and others who engage in this conversation do not always start on the same page. -

Oecd Economic Surveys: Germany 2020 © Oecd 2020 4

OECD Economic Surveys Germany OVERVIEW http://www.oecd.org/economy/germany-economic-snapshot/ Germany This document, as well as any data and any map included herein, are without prejudice to the status of or sovereignty over any territory, to the delimitation of international frontiers and boundaries and to the name of any territory, city or area. The statistical data for Israel are supplied by and under the responsibility of the relevant Israeli authorities. The use of such data by the OECD is without prejudice to the status of the Golan Heights, East Jerusalem and Israeli settlements in the West Bank under the terms of international law. OECD Economic Surveys: Germany© OECD 2020 You can copy, download or print OECD content for your own use, and you can include excerpts from OECD publications, databases and multimedia products in your own documents, presentations, blogs, websites and teaching materials, provided that suitable acknowledgement of OECD as source and copyright owner is given. All requests for public or commercial use and translation rights should be submitted to [email protected]. Requests for permission to photocopy portions of this material for public or commercial use shall be addressed directly to the Copyright Clearance Center (CCC) at [email protected] or the Centre français d’exploitation du droit de copie (CFC) at [email protected] of or sovereignty over any territory, to the delimitation of international frontiers and boundaries and to the name of any territory, city or area. 3 Executive summary OECD ECONOMIC SURVEYS: GERMANY 2020 © OECD 2020 4 The economy is in recession rapid withdrawal of support could derail the recovery, particularly if underlying growth is weak. -

Gross Domestic Product by State Estimation Methodology

Gross Domestic Product by State Estimation Methodology U.S. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE Penny Pritzker, Secretary BUREAU OF ECONOMIC ANALYSIS Brian C. Moyer, Director Sarahelen Thompson, Deputy Director 2017 www.bea.gov Acknowledgments U.S. Department of Commerce Penny Pritzker, Secretary Bureau of Economic Analysis Brian C. Moyer, Director Sarahelen Thompson, Deputy Director Joel D. Platt, Associate Director for Regional Economic Accounts, provided overall guidance for the preparation of this document. Ian Mead, Chief of the Regional Product Division, directed the preparation of this document. i Executive Summary HIS volume presents the conceptual framework, the data sources, and the statistical methodologies used T by the Regional Product Division of the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) to estimate gross domestic product (GDP) by industry for all U.S. states for 1963–2016. GDP by state is the state equivalent of GDP for the nation. In theory, the measurement of GDP for the nation is equal to gross domestic income (GDI). However, because GDP and GDI are measured using different source data, they usually are not equal. The difference between GDP and GDI is displayed in the National Income and Product Accounts (NIPAs) as the statistical discrepancy. GDP is measured as the expenditures of households on goods and services plus business investment, government expen ditures, and net exports. GDI is measured as the factor incomes earned (labor and capital income) and other costs incurred in production. GDP by state is measured as the factor incomes incurred in production, as is GDI. Although GDP by state is measured like GDI, the factor incomes are reconciled with GDP as the final step in the estimation process. -

Time of Troubles: the Yen and Japan's Economy, 1985-2008*

Time of Troubles: The Yen and Japan’s Economy, 1985-2008* Maurice Obstfeld University of California, Berkeley March 2009 Abstract This paper explores the links between macroeconomic developments, especially monetary policy, and the exchange rate during the period of Japan’s bubble economy and subsequent stagnation. The yen experienced epic gyrations over that period, starting with its rapid ascent after the March 1985 Plaza Accord of major industrial countries. Two distinct periods of endaka fukyo, or recession induced by a strong yen, occurred in the late 1980s and the early 1990s at critical phases of the monetary policy cycle. My approach emphasizes the interaction of short-term developments driven by monetary factors (as they affect international real interest rate differentials) and the long-term determinants of the real exchange rate’s equilibrium path. Chief among those long-run determinants are relative sectoral productivity levels and the terms of trade, including the price of oil. Since the mid-1990s, the yen’s real exchange rate has generally followed a depreciating trend and Japan’s comprehensive terms of trade have deteriorated. *Prepared for the ESRI/Chicago GSB/Columbia Business School Conference on “Japan’s Bubble, Deflation, and Long-Term Stagnation,” Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, December 11-12, 2008. I thank Thomas Becker, Gabriel Chodorow-Reich, and Matteo Maggiori for excellent research assistance. The paper has benefited from the helpful suggestions of Mick Devereux, Kyoji Fukao, Linda Goldberg, Koichi Hamada, Takatoshi Ito, Anil Kashyap, Jaewoo Lee, Masao Ogaki, David Weinstein, and participants at the March 2008 Columbia University pre-workshop on “Japan’s Bubble,” the follow-up December 2008 San Francisco Federal Reserve conference, and the November 2008 Swiss National Bank/IMF conference on exchange rates, held in Zürich. -

(For Foundation Students) NATIONAL INCOME

CMA Students Newsletter (For Foundation Students) Special Edition NATIONAL INCOME The definitions of national income can be classified into two groups: Definitions of National Income Traditional Definition Modern Definition "the net "The labour and “National income is that part “The national dividend or output of capital of country of objective income of the income consists solely of commodit acting on its natural community, including of services as received by the ies and resources produce course income derived from ultimate consumers, whether services annually a certain net abroad which can be from their material or from flowing aggregate of measured in money”. human environments. Thus, during the commodities, material a piano or an overcoat year from and immaterial made for me this year is not the A.C. Pigou including services of all a part of this year’s income, country’s kinds. This is the true but an addition to capital. productiv net annual income or Criticism- Only the services rendered e system revenue of the country to me during this year by in the or national dividend.” 1). Unnecessarily these things are income.” differentiate between hands of commodities, which can the ultimate Alfred Marshall and which cannot be exchanged for money. Irving Fisher consumer s”. 2).When only such commodities as can be Criticism- exchanged for money, Simon Kuznets 1) Difficult to have are included in estimation Criticism- of national income, the a correct 1).Difficult to estimate the estimation of national income, be correctly measured. money value of net Goods & Servcices consumption than that of because they are 3).Applicable only to the net production. -

Capital Depreciation and Labor Shares Around the World: Measurement and Implications∗

Capital Depreciation and Labor Shares Around the World: Measurement and Implications∗ Loukas Karabarbounis Brent Neiman University of Chicago and NBER University of Chicago and NBER October 2014 Abstract The labor share is typically measured as compensation to labor relative to gross value added (\gross labor share"), in part because gross value added is more directly measured than net value added. Labor compensation relative to net value added (\net labor share") may be more important in some settings, however, because depreciation is not consumed. In this paper we make three contributions. First, we document that gross and net labor shares generally declined together in most countries around the world over the past four decades. Second, we use a simple economic environment to show that declines in the price of capital necessarily cause gross and net labor shares to move in the same direction, whereas other shocks such as a decline in the real interest rate may cause the net labor share to rise when the gross labor share falls. Third, we illustrate that whether the gross or the net labor share is a more useful proxy for inequality during an economy's transition depends sensitively on the nature of the underlying shocks that hit the economy. JEL-Codes: E21, E22, E23, E25. Keywords: Depreciation, Labor Share, Inequality. ∗We gratefully acknowledge the support of the National Science Foundation, the Business and Public Policy Faculty Research Fund at Chicago Booth, and the Robert King Steel Faculty Fellowship at Chicago Booth. The Online Appendix that accompanies this paper can be found on the authors' web pages. -

Capital Stocks, Capital Services and Depreciation1

CAPITAL STOCKS, CAPITAL SERVICES AND DEPRECIATION1 Peter Hill Introduction This paper is concerned with the measurement of capital stocks, capital services and depreciation in economic accounts. The values of these stocks and flows are all interdependent and they must be measured consistently within a coherent economic theoretic framework. For purposes of this paper, the capital stock consists of all the fixed assets such as machinery, equipment, buildings and other structures used by enterprises to provide inputs of capital services into processes of production. The values of fixed assets to their owners depend on the flows of capital services they are capable of contributing as inputs into production over their service lives. As depreciation represents the decline in the value of a fixed asset over time, depreciation also depends on the service flows. Despite the central role played by capital services, however, they do not appear in the production account of the 1993 System of National Accounts, or SNA, or indeed anywhere in that system. This is a serious omission which greatly reduces the analytical usefulness of the accounts and may cause the data to be misinterpreted. The values of stocks of fixed assets appear in the opening and closing balance sheets of the SNA while depreciation is recorded in the production and capital accounts. Capital services should also be recorded in the production account, but are not so at present. This paper describes the underlying economic theory linking all these stocks and flows together. It is shown that two concepts of economic depreciation exist. One is the traditional accounting concept, described here as time series depreciation, which measures the change in the value of an individual asset over time. -

Consumption of Fixed Capital on Roads and Other Public

NATIONAL ACCOUNTS Jukka Jalava, Taru Sandström Consumption of Fixed Capital on Roads and Other Public Infrastructure in the Finnish National Accounts Workshop on the Implementation of ESA95: Achieving Comparability in Practice, 7-9.6.1999, Copenhagen, Denmark. Abstract One of the major changes for the Finnish National Accounts in implementing ESA95, was the calculation of consumption of fixed capital (CFC) on public infra- structure, especially as this has direct implications on GDP. This paper starts by briefly describing the perpetual inventory method used in Finland, and how con- sumption of fixed capital is calculated. Then the data sources for central and local government GFCF are described. A comparison of length of service lives (and degree of road utilization) with Finnish, Norwegian and Swedish data is done, as well as calculations with different service lives for CFC on Finnish public roads, and the potential impacts of these calculations on GDP. PIM In Finland (as well as in all other OECD countries), the Perpetual Inventory Method (PIM) is used for the calculation of capital stock and consumption of fixed capital estimates. For its calculations, the PIM uses as inputs long series of gross fixed capital formation at constant prices (by industry and asset type), price in- dexes, and assumptions of service lives, survival functions and depreciation pat- terns1. Finnish capital stock calculations have been revised. Physically, the Dyalog APL- software was found to be optimal. While being compatible with the National Ac- counts new adp-environment, it still facilitates the specific demands made by capital stock calculations. Otherwise, the extension of the concept of capital for- mation (due to the implementation of ESA95), and the change of base year from 1990 to 1995, were the biggest changes. -

LESSONS from the GERMAN INFLATION EXPERIENCE of the 1920S

NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES STOPPING HYPERINFLATION: LESSONS FROM THE GERMAN INFLATION EXPERIENCE OF THE 1920s Rudiger Dornbusch Working Paper No. 1675 NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 August 1985 The research reported here is part of the NBER1s research programs in International Studies and Development of the American Economy. Any opinions expressed are those of the author and not those of the National Bureau of Economic Research. NBER Working Paper #1675 August 1985 Stopping Hyperinflation: Lessons from the German Inflation Experience of the 1920s ABSTRACT The special role of money in the hyperinflation process, and particularly in the stabilization phase, has now been reconsidered in a best- selling essay by Sargent. The message is that credible fiscal stabilization is the sine qua non of stopping inflation. This is definitely not viewed as being in conflict with the monetary hypothesis, but it does represent a shift of emphasis. We draw attention to a third aspect of the hyperinflation process, and the stablization, namely exchange rate and interest rate policy. Even though a government may accomplish all the right measures in terms of budget stablization or control of money creation, there remains the problem of making these measures credible and hence being able to actually achieve them. We argue that exchange rate and interest rate policy in the transition have traditionally formed the vehicle for establishing that credibility by a de facto stablization. We make that point by discussing the events of the German hyperinflation. In that case the stablization was a much more diffuse, accidental matter than a reading of the classics reveals with exchange rate policy playing a key role.