Gross Domestic Product by State Estimation Methodology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

National Income in India, Concept and Measurement

National Income in India, Concept and Measurement National Income :- • National income is the money value of all the final goods and services produced by a country during a period of one year. National income consists of a collection of different types of goods and services of different types. • Since these goods are measured in different physical units it is not possible to add them together. Thus we cannot state national income is so many millions of meters of cloth. Therefore, there is no way except to reduce them to a common measure. This common measure is money. Basic Concepts in National Income:- • Gross domestic product • Gross domestic product at constant price and at current price • Gross domestic product at factor cost and Gross domestic product at market price • Net domestic product • Gross national product • Net national Product • Net national product at factor cost or national income Gross Domestic Product • Gross domestic product is the money value of all final goods and services produced in the domestic territory of a country during an accounting year. Gross Domestic Product at Constant price and Current price • GDP can be estimated at current prices and at constant prices. If the domestic product is estimated on the basis of the prevailing prices it is called gross domestic product at current prices. • If GDP is measured on the basis of some fixed price, that is price prevailing at a point of time or in some base year it is known as GDP at constant price or real gross domestic product. GDP at Factor cost and GDP at Market price • The contribution of each producing unit to the current flow of goods and services is known as the net value added. -

The Yen and the Japanese Economy, 2004

8 The Yen and the Japanese Economy, 2004 TAKATOSHI ITO This chapter presents an overview of the Japanese macroeconomy and its exchange rate policy and monetary policy in the period 2003–04. It also examines the effects of the exchange rate changes on Japanese trade bal- ances. The monetary authorities of Japan—namely, the Ministry of Finance and the Bank of Japan (MOF-BOJ)—intervened in the foreign exchange market frequently heavily in 2003–04. The authorities sold ¥35 trillion (or $320 billion), 7 percent of the Japanese GDP, between January 2003 and March 2004. This chapter examines the presumed objectives of the large interventions and their effectiveness. Why the Japanese authorities inter- vened to this unprecedented extent is explained here in the context of the macroeconomic conditions and developments in the foreign exchange, spot, and futures markets. To summarize the chapter’s conclusions, interventions were conducted for several reasons—including to prevent “premature” appreciation in the midst of a weak economy, to help monetary policy by providing opportu- nities for unsterilized interventions, and to defuse excessive speculative pressure. These hypotheses on the motivations for intervention are sup- ported by data, but it is more difficult to judge whether the intended effects of the MOF-BOJ’s actions were achieved. Japan’s macroeconomic conditions are described in the chapter’s second section. The third section examines the relationship between the exchange rate and net exports of Japan. The next sections explains the reasons for heavy interventions from January 2003 to March 2004 and section provide data to back up these explanations. -

Operating Surplus (Income from Property)

Class No.9: Unit 1 (National Income and related aggregates) Objective: After the class/ content you will become familiar with the components of operating surplus (income from property) Operating surplus: It is an income generated from property (rent + interest) and income from entrepreneurship (profit). Royalty is included in rent. Alternatively, it is the sum of rent, interest and profit. We can also define ‘It is Net value added at FC (i.e. domestic income) minus Compensation of employees (traditionally called wages) and mixed income of self-employed.’ Factor income (NDPFc) Mixed income of self Compensation of employees Operating surplus employed Income from property Income from entrepreneurship Rent Royalty interest Profit dividend profit tax Undistributed profit (Note: Interest on National Debt is not the part of Interest from property and thus it is ignored) Components of operating surplus: (1) Income from Property: It is an income generated from the property in form of rent, interest and royalty. (i) Rent: It is any periodic payment to an owner or factor of production in excess of the costs needed to bring that factor into production. It also refers as ‘Economic surplus’ as it is received by landlord without any effort. (ii) Royalty: A royalty is a legally-binding payment made to an individual, for using his or her originally- created assets, including copyrighted works, franchises, and natural resources. For example, use of mineral deposit such as coal, oil etc. Royalty is also associated with musicians, who receive such payments whenever their originally-recorded songs are played on the radio or television, used in movies, performed at concerts, bars, and restaurants, or consumed via streaming services. -

Modeling the Economic Surplus in a SAM

Modeling the Economic Surplus in a SAM Framework Erik K. Olsen Dept. of Economics Univ. of Missouri Kansas City 5100 Rockhill Rd. Kansas City, MO 64110 [email protected] June 21, 2011 1 Introduction The concept of an economic surplus is something that Marxian and Sra¢ an economics share in common. Both theories recognize the importance of an eco- nomic surplus that is produced and subsequently utilized for various purposes, but they each de…ne this surplus in very di¤erent ways. The surplus of Sra¢ an theory is the net product of the economy as de…ned in conventional national accounts. The surplus in Marxian theory is de…ned through its class theory. Draft prepared for 2011 Association for Heterodox Economics conference, Nottingham Trent University. 1 From the Marxist perspective the surplus created by production provides the resources that support the array of nonproduction activities associated with the capitalist enterprise as well as for many activities and individuals that may be quite distant. Shareholders of a corporation, for example, receive an in- come derived from the surplus created in production, but this is simply one of many potential uses. Identifying the connection between the surplus created in production and the subsequent recipients is the task of Marxian class theory, and this provides a means to understand how the surplus created in production plays a role in the reproduction of the economic system itself. This emphasis on a complex class structure that is part of the fabric of the economy is what distinguishes Marxian class theory from the Sra¢ an one, and it is also what distinguishes their two di¤erent theories of surplus. -

17 National Accounts and Economic Statistics STD/NAES(2005)

For Official Use STD/NAES(2005)17 Organisation de Coopération et de Développement Economiques Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development 29-Sep-2005 ___________________________________________________________________________________________ English - Or. English STATISTICS DIRECTORATE For Official Use STD/NAES(2005)17 National Accounts and Economic Statistics COST OF CAPITAL SERVICES AND THE NATIONAL ACCOUNTS UPDATE OF THE 1993 SNA - ISSUE No. 15 ISSUES PAPER FOR THE JULY 2005 AEG MEETING This paper has been prepared by Paul Schreyer, W. Erwin Diewert and Anne Harrison WORKING PARTY ON NATIONAL STATISTICS To be held on 11 - 14 October 2005 Tour Europe - Paris La Défense Beginning at 9:30 a.m. on the first day English - Or. English JT00190606 Document complet disponible sur OLIS dans son format d'origine Complete document available on OLIS in its original format STD/NAES(2005)17 COST OF CAPITAL SERVICES AND THE NATIONAL ACCOUNTS SNA/M1.05/04 UPDATE OF THE 1993 SNA - ISSUE No. 15 ISSUES PAPER FOR THE JULY 2005 AEG MEETING Paul Schreyer W. Erwin Diewert Anne Harrison EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Background 1. The topic of capital services has been discussed in various Canberra II Group meetings, including those of October 2003, April 2004, September 2004 and April 2005. It has also been discussed in meetings in Eurostat, at the OECD national accounts meeting and at the AEG meeting in December 2004. At its latest meeting in April 2005, the Canberra II Group supported the recommendations in the paper by Schreyer, Diewert and Harrison (2005) with some minor modifications. 2. The main messages to emerge from all of the meetings listed above is clear; few countries at present have a sufficiently detailed capital stock database to present robust capital service figures and even of those which do, not all are yet ready to publish these data as part of the main national accounts. -

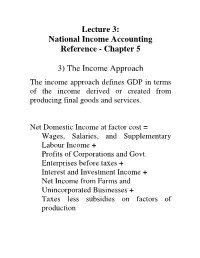

Lecture 3: National Income Accounting Reference - Chapter 5

Lecture 3: National Income Accounting Reference - Chapter 5 3) The Income Approach The income approach defines GDP in terms of the income derived or created from producing final goods and services. Net Domestic Income at factor cost = Wages, Salaries, and Supplementary Labour Income + Profits of Corporations and Govt. Enterprises before taxes + Interest and Investment Income + Net Income from Farms and Unincorporated Businesses + Taxes less subsidies on factors of production Net Domestic Income at market prices = Net Domestic Income at factor cost + Indirect taxes less subsidies Gross Domestic Product (GDP) at market prices = Net Domestic Income at market prices + Capital Consumption Allowances + Statistical Discrepancy OTHER NATIONAL ACCOUNTS Gross National Product (GNP) = Gross Domestic Product (GDP) + Net Investment from Non-residents = 1154.9 – 84.9 = 1070 Example – The production of cars in the Honda factory in Alliston, Ontario is included in both Canadian GDP and GNP. But GNP excludes profit sent to foreign shareholders of Honda, but this profit is included in Canadian GDP. Net Domestic Product (NDP) = GNP – Depreciation = 1070–155 = 915 Net National Income at Basic Prices (NNI) = NDP- Taxes less subsidies on factors of production - Indirect taxes less subsidies = 915 – 53.8 – 84.4 = 776.8 Personal Income = NNI – Undistributed Corporate Profits + Govt. Transfer Payments = 776.8 – 49.0 +71.3 = 848.1 Disposable Income = PI – Personal Taxes = 848 – 152.2 = 695.9 Nominal GDP Versus Real GDP Nominal GDP is the GDP measured in terms of the price level at the time of measurement (unadjusted for inflation). Problem: How can we compare the market values of GDP from year to year if the value of money itself changes because of inflation or deflation? - Compare 5% increase in Q with no change in P and 5% increase in P with no change in Q - The way around this problem is to deflate GDP when prices rise and to inflate GDP when prices fall. -

GDP As a Measure of Economic Well-Being

Hutchins Center Working Paper #43 August 2018 GDP as a Measure of Economic Well-being Karen Dynan Harvard University Peterson Institute for International Economics Louise Sheiner Hutchins Center on Fiscal and Monetary Policy, The Brookings Institution The authors thank Katharine Abraham, Ana Aizcorbe, Martin Baily, Barry Bosworth, David Byrne, Richard Cooper, Carol Corrado, Diane Coyle, Abe Dunn, Marty Feldstein, Martin Fleming, Ted Gayer, Greg Ip, Billy Jack, Ben Jones, Chad Jones, Dale Jorgenson, Greg Mankiw, Dylan Rassier, Marshall Reinsdorf, Matthew Shapiro, Dan Sichel, Jim Stock, Hal Varian, David Wessel, Cliff Winston, and participants at the Hutchins Center authors’ conference for helpful comments and discussion. They are grateful to Sage Belz, Michael Ng, and Finn Schuele for excellent research assistance. The authors did not receive financial support from any firm or person with a financial or political interest in this article. Neither is currently an officer, director, or board member of any organization with an interest in this article. ________________________________________________________________________ THIS PAPER IS ONLINE AT https://www.brookings.edu/research/gdp-as-a- measure-of-economic-well-being ABSTRACT The sense that recent technological advances have yielded considerable benefits for everyday life, as well as disappointment over measured productivity and output growth in recent years, have spurred widespread concerns about whether our statistical systems are capturing these improvements (see, for example, Feldstein, 2017). While concerns about measurement are not at all new to the statistical community, more people are now entering the discussion and more economists are looking to do research that can help support the statistical agencies. While this new attention is welcome, economists and others who engage in this conversation do not always start on the same page. -

For Official Use STD/NA(99)54

For Official Use STD/NA(99)54 Organisation de Coopération et de Développement Economiques OLIS : 01-Sep-1999 Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development Dist. : 02-Sep-1999 __________________________________________________________________________________________ Or. Eng. STATISTICS DIRECTORATE For Official Use STD/NA(99)54 National Accounts REVISION DUTCH NATIONAL ACCOUNTS; FIRST RESULTS AND BACKGROUNDS Agenda item 13 Statistics Netherlands OECD MEETING OF NATIONAL ACCOUNTS EXPERTS Château de la Muette, Paris 21-24 September 1999 Beginning at 9:30 a.m. on the first day Or. Eng. 80957 Document complet disponible sur OLIS dans son format d'origine Complete document available on OLIS in its original format STD/NA(99)54 REVISION DUTCH NATIONAL ACCOUNTS; FIRST RESULTS AND BACKGROUNDS Gert Buiten, Jacqueline van den Hof and Peter van de Ven Summary and introduction As in many other countries, the national accounts of The Netherlands have been revised, in accordance with the new worldwide System of National Accounts (SNA) 1993, and its European equivalent, the European System of National and Regional Accounts (ESA) 1995. As a consequence, the new national accounts data give a better picture of a number of recent developments, like the expanding importance of services, automation, information and knowledge. In addition, new statistical insights and results have been incorporated. The revision has implications for the macro-economic description and for a number of policy indicators. For the year 1995, Gross Domestic Product (GDP) has been adjusted upwards by 26.4 billion guilders, an increase of 4.1%. The upward adjustment is largely caused by the implementation of the new international guidelines. The net national income (NNI) has increased less (1.1%), since a large part of the changes concerns an upward adjustment of consumption of fixed capital. -

Surplus-Value and Aggregate Concentration in the Uk Economy, 1987-2009

DISCUSSION PAPERS IN ECONOMICS No. 2010/10 ISSN 1478-9396 SURPLUS-VALUE AND AGGREGATE CONCENTRATION IN THE UK ECONOMY, 1987-2009 VITOR LEONE and BRUCE PHILP December 2010 1 DISCUSSION PAPERS IN ECONOMICS The economic research undertaken at Nottingham Trent University covers various fields of economics. But, a large part of it was grouped into two categories, Applied Economics and Policy and Political Economy . This paper is part of the new series, Discussion Papers in Economics . Earlier papers in all series can be found at: http://www.ntu.ac.uk/research/academic_schools/nbs/w orking_papers/index.html Enquiries concerning this or any of our other Discussion Papers should be addressed to the Editorial team: Dr. Simeon Coleman, Email: [email protected] Dr. Marie Stack, Email: [email protected] Dr. Dan Wheatley, Email: [email protected] Division of Economics Nottingham Trent University Burton Street, Nottingham, NG1 4BU UNITED KINGDOM 2 SURPLUS -VALUE AND AGGREGATE CONCENTRATION IN THE UK ECONOMY , 1987-2009 Vitor Leone Bruce Philp 1 Abstract This paper examines the movements in the Marxian surplus-value rate using a Quantitative Marxist methodology. It examines the relationship between surplus-value and the degree of monopoly power in the UK economy using quarterly data and a proxy for aggregate concentration — the ratio of market capitalisation in FTSE100 firms to market capitalisation in FTSE All Share firms. Two other forces are considered: (i) the size of the “reserve army” of the unemployed; (ii) working class militancy. Our results suggest that increases in the “reserve army” influence the surplus-value rate positively, and that working class militancy is negatively related to changes in the surplus-value rate, indicating that strike action in this period is largely a defensive measure by workers. -

Oecd Economic Surveys: Germany 2020 © Oecd 2020 4

OECD Economic Surveys Germany OVERVIEW http://www.oecd.org/economy/germany-economic-snapshot/ Germany This document, as well as any data and any map included herein, are without prejudice to the status of or sovereignty over any territory, to the delimitation of international frontiers and boundaries and to the name of any territory, city or area. The statistical data for Israel are supplied by and under the responsibility of the relevant Israeli authorities. The use of such data by the OECD is without prejudice to the status of the Golan Heights, East Jerusalem and Israeli settlements in the West Bank under the terms of international law. OECD Economic Surveys: Germany© OECD 2020 You can copy, download or print OECD content for your own use, and you can include excerpts from OECD publications, databases and multimedia products in your own documents, presentations, blogs, websites and teaching materials, provided that suitable acknowledgement of OECD as source and copyright owner is given. All requests for public or commercial use and translation rights should be submitted to [email protected]. Requests for permission to photocopy portions of this material for public or commercial use shall be addressed directly to the Copyright Clearance Center (CCC) at [email protected] or the Centre français d’exploitation du droit de copie (CFC) at [email protected] of or sovereignty over any territory, to the delimitation of international frontiers and boundaries and to the name of any territory, city or area. 3 Executive summary OECD ECONOMIC SURVEYS: GERMANY 2020 © OECD 2020 4 The economy is in recession rapid withdrawal of support could derail the recovery, particularly if underlying growth is weak. -

PALGRAVE: a Dictionary of Economics (Editor with Murray Milgate and Peter Newman)

Also by Philip Arestls THE POLITICAL ECONOMY OP ECONOMIC POLICIES (co-editor with Malcolm Sawyer) Issues in Finance and MONEY AND BANKING: Issues for the Twenty-Pirst Century (editur) MONEY, PRICING, DISTRIBUTION AND ECONOMIC INTEGRATION Industry RELEVANCE OF KEYNESIAN ECONOMIC POLICIES TODAY (co-editor with Malcolm Sawyer) WHAT GLOBAL ECONOMIC CRISIS? (co-editur with Michelle l1addeley and fohn McCombie) Essays in Honour of Ajit Singh POST-BUBBLE US ECONOMY: Implications for Financial Markets and the Economy (with Elias Karakitsos) FINANCIAL DEVELOPMENTS IN NATlONALAND INTERNATIONAL MARKETS (co-editor with Jesus Ferreiro and Felipe Serrano) Edited by ADVANCES IN MONETARY POLICY AND MACROECONOMICS (co-editor with Gennaro Zezza) Philip Arestis ASPECTS OF MODERN MONETARY AND MACROECONOMIC POLICIES (co-editor with Eckhard Hdn and Edwin Le Heron) and ON MONEY, METHOD AND KEYNES: Selected Essays by Victoria Chick (co-editor with Sheila Dow) John Eatwell IS THERE A NEW CONSENSUS IN MACROECONOMICS? (editor) POLITICAL ECONOMY OF BRAZIL (co-editor with Alfredo Saad-Filho) FINANCIAL LIBERALIZATION AND ECONOMIC PERFORMANCE IN EMERGING COUNTRIES (co-editor with Luiz Fernando de Paula) Also by fohn Eatwell AN INTRODUCTION TO MODERN ECONOMICS (with Joan Robinson) WHATEVER HAPPENED TO BRITAIN? KEYNES'S ECONOMICS AND THE THEORY OF VALUE AND DISTRIBUTION (editor with Murray Milgate) THE NEW PALGRAVE: A Dictionary of Economics (editor with Murray Milgate and Peter Newman) THE WORLD OF ECONOMICS (editor with Murray Mi/gate and Peter Newman) THE NEW PALGRAVE -

BUSINESS ACCOUNTS Chapter 7

Chapter 7 BUSINESS ACCOUNTS 1. The relationship between the firm (enterprise) and the corporation 2. The structure of corporate-sector accounts 3. From corporations to firms 7 BUSINESS ACCOUNTS CHAPTER 7 Business Accounts OECD economists are particularly interested in the institutional framework in which enterprises (firms) operate, in order to identify how to improve firms’ performance and generate an increase in employment, among other benefits. In recent OECD reports on France, for example, the authors have suggested a certain number of structural reforms intended to improve the performance of French firms. For example: ● ease the employment regulations that hinder layoffs and discriminate against small innovative units that need to be able to adjust their scale and the composition of their workforce; ● further deregulate the markets for goods and services, which remain highly regulated in France and hamper competition. The OECD economists cite the example of retail distribution, where the legislation was initially designed to prevent the large firms from wiping out the small ones, but it has on the contrary discouraged new entrants and handed over domination to a few large firms; ● improve the efficiency of the public sector, in other words general government and firms controlled by general government, which remains very large in France and partly explains the high rate of corporate tax compared with other OECD countries, acting as a brake on direct investment by foreign firms in France; and ● complete the establishment of a competitive market for network industries. Under pressure from Europe, France has liberalised its transport and telecommunications networks, but has not yet fully done so for energy.