Introductions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Antisemitism in the Radical Left and the British Labour Party, by Dave Rich

Kantor Center Position Papers Editor: Mikael Shainkman January 2018 ANTISEMITISM IN THE RADICAL LEFT AND THE BRITISH LABOUR PARTY Dave Rich* Executive Summary Antisemitism has become a national political issue and a headline story in Britain for the first time in decades because of ongoing problems in the Labour Party. Labour used to enjoy widespread Jewish support but increasing left wing hostility towards Israel and Zionism, and a failure to understand and properly oppose contemporary antisemitism, has placed increasing distance between the party and the UK Jewish community. This has emerged under the leadership of Jeremy Corbyn, a product of the radical 1960s New Left that sees Israel as an apartheid state created by colonialism, but it has been building on the fringes of the left for decades. Since Corbyn became party leader, numerous examples of antisemitic remarks made by Labour members, activists and elected officials have come to light. These remarks range from opposition to Israel’s existence or claims that Zionism collaborated with Nazism, to conspiracy theories about the Rothschilds or ISIS. The party has tried to tackle the problem of antisemitism through procedural means and generic declarations opposing antisemitism, but it appears incapable of addressing the political culture that produces this antisemitism: possibly because this radical political culture, borne of anti-war protests and allied to Islamist movements, is precisely where Jeremy Corbyn and his closest associates find their political home. A Crisis of Antisemitism Since early 2016, antisemitism has become a national political issue in Britain for the first time in decades. This hasn’t come about because of a surge in support for the far right, or jihadist terrorism against Jews. -

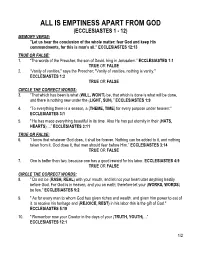

Is Emptiness Apart From

ALL IS EMPTINESS APART FROM GOD (ECCLESIASTES 1 - 12) MEMORY VERSE: "Let us hear the conclusion of the whole matter: fear God and keep His commandments, for this is man's all.” ECCLESIASTES 12:13 TRUE OR FALSE: 1. “The words of the Preacher, the son of David, king in Jerusalem.” ECCLESIASTES 1:1 TRUE OR FALSE 2. “Vanity of vanities," says the Preacher; "Vanity of vanities, nothing is vanity." ECCLESIASTES 1:2 TRUE OR FALSE CIRCLE THE CORRECT WORDS: 3. “That which has been is what (WILL, WON’T) be, that which is done is what will be done, and there is nothing new under the (LIGHT, SUN)." ECCLESIASTES 1:9 4. "To everything there is a season, a (THEME, TIME) for every purpose under heaven:" ECCLESIASTES 3:1 5. " He has made everything beautiful in its time. Also He has put eternity in their (HATS, HEARTS) ...” ECCLESIASTES 3:11 TRUE OR FALSE: 6. “I know that whatever God does, it shall be forever. Nothing can be added to it, and nothing taken from it. God does it, that men should fear before Him.” ECCLESIASTES 3:14 TRUE OR FALSE 7. One is better than two, because one has a good reward for his labor. ECCLESIASTES 4:9 TRUE OR FALSE CIRCLE THE CORRECT WORDS: 8. " Do not be (RASH, REAL) with your mouth, and let not your heart utter anything hastily before God. For God is in heaven, and you on earth; therefore let your (WORKS, WORDS) be few." ECCLESIASTES 5:2 9. " As for every man to whom God has given riches and wealth, and given him power to eat of it, to receive his heritage and (REJOICE, REST) in his labor-this is the gift of God." ECCLESIASTES 5:19 10. -

10 WINTER 1986 Ffl Jiiirfuijtjjrii-- the Stemberg Centre for Judaism, the Manor House , 80 East End Road, Contents London N3 2SY Telephone: 01-346 2288

NA NUMBEFt 10 WINTER 1986 ffl jiiirfuijTJJriI-- The Stemberg Centre for Judaism, The Manor House , 80 East End Road, Contents London N3 2SY Telephone: 01-346 2288 2 Jaclynchernett We NowNeeda separate MANNA is the Journal of the Sternberg Conservative Movement Centre for Judaism at the Manor House and of the Manor House Society. 3 MichaelLeigh Andwhywe Mus.tTake upthe challenge MANI`IA is published quarterly. 4 Charlesselengut WhyYoung Jews Defectto cults Editor: Rabbi Tony Bayfield Deputy Editor: Rabbi william Wolff Art Editor: Charles Front 8 LionelBlue lnklings Editorial Assistant: Elizabeth Sarah Curtis cassell Help! Editorial Board: Rabbi Colin Eimer, 10 ^ Deirdreweizmann The outsider Getting Inside Rabbi Dr. Albert Friedlander, Rabbi the Jewish Skin David Goldberg, Dr. Wendy Green- gross, Reverend Dr. Isaac Levy, Rabbi Dr. Jonathan Magonet, Rabbi Dow Mamur, Rabbi Dr. J.ohm Rayner, Pro- 12 LarryTabick MyGrandfather Knew Isaac Bashevis singer fessor J.B . Segal, Isca Wittenberg. 14 Wendy Greengross Let's pretend Views expressed in articles in M¢7!#cz do not necessarily reflect the view of the Editorial Board. 15 JakobJ. Petuchowski The New Machzor. Torah on One Foot Subscription rate: £5 p.a. (four issues) including postage anywhere in the U.K. 17 Books. Lionel Blue: From pantryto pulpit Abroad: Europe - £8; Israel, Asia; Evelyn Rose: Blue's Blender Americas, Australasia -£12. 18 Reuven silverman Theycould Ban Baruch But Not His Truth A 20 Letters 21 DavjdGoldberg Lastword The cover shows Zlfee Jew by Jacob Kramer, an ink on yellow wash, circa 1916, one of many distinguished pic- tures currently on exhibition at the Stemberg Centre. -

Rabbi Andre Ungar Z’L (21 July 1929–5 May 2020)

Rabbi Andre Ungar z’l (21 July 1929–5 May 2020) Jonathan Magonet abbi Ungar was born in Budapest to Bela and Frederika Ungar. The Rfamily lived in hiding with false identity papers from 1944 under the German occupation.1 After the war, a scholarship brought him to the UK where he studied at Jews’ College, then part of University College, and subsequently studied philosophy. Feeling uncomfortable within Orthodoxy, he met with Rabbi Harold Reinhart and Rabbi Leo Baeck and eventually became an assistant rabbi at West London Synagogue. In 1954 he obtained his doctorate in philosophy and was ordained as a rabbi through a programme that preceded the formal creation of Leo Baeck College in 1956. In 1955 he was appointed as rabbi at the pro- gressive congregation in Port Elizabeth, South Africa. Very soon his fiery anti-Apartheid sermons were condemned in the Afrikaans newspapers and received mixed reactions from the Jewish community. In December 1956 he was served with a deportation order and was forced to leave the country. He wrote with passion about his South African experience some ten years later in the book Resistance against Tyranny2 A symposium edited by his friend and fellow Hungarian Eugene Heimler whose important account of his Holocaust experience Night of the Mist Ungar had translated into English. I found that our own genteel white leisure and wealth was a thin veneer over a vast mass of coloured suffering; and that the distinction was arti- ficially created, maintained and, since the Nationalist victory of 1948, deliberately worsened day after day. -

Ecclesiastes Song of Solomon

Notes & Outlines ECCLESIASTES SONG OF SOLOMON Dr. J. Vernon McGee ECCLESIASTES WRITER: Solomon. The book is the “dramatic autobiography of his life when he got away from God.” TITLE: Ecclesiastes means “preacher” or “philosopher.” PURPOSE: The purpose of any book of the Bible is important to the correct understanding of it; this is no more evident than here. Human philosophy, apart from God, must inevitably reach the conclusions in this book; therefore, there are many statements which seem to contra- dict the remainder of Scripture. It almost frightens us to know that this book has been the favorite of atheists, and they (e.g., Volney and Voltaire) have quoted from it profusely. Man has tried to be happy without God, and this book shows the absurdity of the attempt. Solomon, the wisest of men, tried every field of endeavor and pleasure known to man; his conclusion was, “All is vanity.” God showed Job, a righteous man, that he was a sinner in God’s sight. In Ecclesiastes God showed Solomon, the wisest man, that he was a fool in God’s sight. ESTIMATIONS: In Ecclesiastes, we learn that without Christ we can- not be satisfied, even if we possess the whole world — the heart is too large for the object. In the Song of Solomon, we learn that if we turn from the world and set our affections on Christ, we cannot fathom the infinite preciousness of His love — the Object is too large for the heart. Dr. A. T. Pierson said, “There is a danger in pressing the words in the Bible into a positive announcement of scientific fact, so marvelous are some of these correspondencies. -

Prayer and Liturgy

Reform Judaism: In 2000 Words Prayer and Liturgy Context The liturgy that we hold in our hands as we pray articulates our values, expresses our concerns, provides language and structure for our communal worship. As Reform Jews we believe that it must therefore evolve to reflect who we are, to speak as we speak. Indeed, liturgy has never been static; it has always grown and changed, influenced by where Jews lived, their experiences and their relationships with those around them. This week, not one essay but two, reflecting the importance of liturgical development in Reform Judaism. In these articles, Rabbi Professor Jonathan Magonet, former Principal of the Leo Baeck College and Rabbi Paul Freedman of Radlett Reform Synagogue, both of whom have edited Reform liturgies, explore some of the major changes in the liturgical life of our community over the last century. Content – Rabbi Professor Jonathan Magonet The liturgy, prayers and forms of service of the UK Reform Movement, like those of the many versions of non- Orthodox Judaism worldwide, are dynamic and ever changing. This often leads to the charge of being ‘fashionable’ and therefore somehow superficial. However, a look at the difference between the siddur in use from 1931 until the major revision in 1977 is a stark reminder that between those two dates the Jewish people experienced two major world-shaking events, the Shoah (Holocaust) and the creation of the State of Israel. Not to have changed, not to have taken these into account, would have been absurd, irrespective of any ‘progressive’ ideological concerns. Perhaps less dramatic but equally significant in terms of the wider society in which we live, the recognition of gender inequality and the wish to address it clearly within the movement, had to be reflected in the ‘new’ siddur published in 2008 – not for the sake of being ‘trendy’ but because a religious tradition that is out of touch with the forces affecting its members becomes at best a mere cult and at worst asks its members to hold very different ideals in their ritual and daily lives. -

Jewish Philosophy and Western Culture Jewish Prelims I-Xvi NEW.Qxp 25/10/07 14:06 Page Ii

Jewish_Prelims_i-xvi NEW.qxp 25/10/07 14:06 Page i Jewish Philosophy and Western Culture Jewish_Prelims_i-xvi NEW.qxp 25/10/07 14:06 Page ii ‘More than just an introduction to contemporary Jewish philosophy, this important book offers a critique of the embedded assumptions of contemporary post-Christian Western culture. By focusing on the suppressed or denied heritage of Jewish and Islamic philosophy that helped shape Western society, it offers possibilities for recovering broader dimensions beyond a narrow rationalism and materialism. For those impatient with recent one-dimensional dismissals of religion, and surprised by their popularity, it offers a timely reminder of the sources of these views in the Enlightenment, but also the wider humane dimensions of the religious quest that still need to be considered. By recognising the contribution of gender and post-colonial studies it reminds us that philosophy, “the love of wisdom”, is still concerned with the whole human being and the complexity of personal and social relationships.’ Jonathan Magonet, formerly Principal of Leo Baeck College, London, and Vice-President of the Movement for Reform Judaism ‘Jewish Philosophy and Western Culture makes a spirited and highly readable plea for “Jerusalem” over “Athens” – that is, for recovering the moral and spiritual virtues of ancient Judaism within a European and Western intellectual culture that still has a preference for Enlightenment rationalism. Victor Seidler revisits the major Jewish philosophers of the last century as invaluable sources of wisdom for Western philosophers and social theorists in the new century. He calls upon the latter to reclaim body and heart as being inseparable from “mind.”’ Peter Ochs, Edgar Bronfman Professor of Modern Judaic Studies, University of Virginia Jewish_Prelims_i-xvi NEW.qxp 25/10/07 14:06 Page iii JEWISH PHILOSOPHY AND WESTERN CULTURE A Modern Introduction VICTOR J. -

Ecclesiastes – “It’S ______About _____”

“DISCOVERING THE UNREAD BESTSELLER” Week 18: Sunday, March 25, 2012 ECCLESIASTES – “IT’S ______ ABOUT _____” BACKGROUND & TITLE The Hebrew title, “___________” is a rare word found only in the Book of Ecclesiastes. It comes from a word meaning - “____________”; in fact, it’s talking about a “_________” or “_________”. The Septuagint used the Greek word “__________” as its title for the Book. Derived from the word “ekklesia” (meaning “assembly, congregation or church”) the title again (in the Greek) can simply be taken to mean - “_________/_________”. AUTHORSHIP It is commonly believed and accepted that _________authored this Book. Within the Book, the author refers to himself as “the son of ______” (Ecclesiastes 1:1) and then later on (in Ecclesiastes 1:12) as “____ over _____ in Jerusalem”. Solomon’s extensive wisdom; his accomplishments, and his immense wealth (all of which were God-given) give further credence to his work. Outside the Book, _______ tradition also points to Solomon as author, but it also suggests that the text may have undergone some later editing by _______ or possibly ____. SNAPSHOT OF THE BOOK The Book of Ecclesiastes describes Solomon’s ______ for meaning, purpose and satisfaction in life. The Book divides into three different sections - (1) the _____ that _______ is ___________ - (Ecclesiastes 1:1-11); (2) the ______ that everything is meaningless (Ecclesiastes 1:12-6:12); and, (3) the ______ or direction on how we should be living in a world filled with ______ pursuits and meaninglessness (Ecclesiastes 7:1-12:14). That last section is important because the Preacher/Teacher ultimately sees the emptiness and futility of all the stuff people typically strive for _____ from God – p______ – p_______ – p________ - and p________. -

Labour, Antisemitism and the News – a Disinformation Paradigm

Labour, Antisemitism and the News A disinformation paradigm Dr Justin Schlosberg Laura Laker September 2018 2 Executive Summary • Over 250 articles and news segments from the largest UK news providers (online and television) were subjected to in-depth case study analysis involving both quantitative and qualitative methods • 29 examples of false statements or claims were identified, several of them made by anchors or correspondents themselves, six of them surfacing on BBC television news programmes, and eight on TheGuardian.com • A further 66 clear instances of misleading or distorted coverage including misquotations, reliance on single source accounts, omission of essential facts or right of reply, and repeated value-based assumptions made by broadcasters without evidence or qualification. In total, a quarter of the sample contained at least one documented inaccuracy or distortion. • Overwhelming source imbalance, especially on television news where voices critical of Labour’s code of conduct were regularly given an unchallenged and exclusive platform, outnumbering those defending Labour by nearly 4 to 1. Nearly half of Guardian reports on the controversy surrounding Labour’s code of conduct featured no quoted sources defending the party or leadership. The Media Reform Coalition has conducted in-depth research on the controversy surrounding antisemitism in the Labour Party, focusing on media coverage of the crisis during the summer of 2018. Following extensive case study research, we identified myriad inaccuracies and distortions in online and television news including marked skews in sourcing, omission of essential context or right of reply, misquotation, and false assertions made either by journalists themselves or sources whose contentious claims were neither challenged nor countered. -

Ecclesiastes: the Philippians of the Old Testament

Ecclesiastes: The Philippians of the Old Testament Bereans Adult Bible Fellowship Placerita Baptist Church 2010 by William D. Barrick, Th.D. Professor of OT, The Master’s Seminary Chapter 12 Life Under a Setting Sun In conclusion, the Preacher determines to fear God, obey God, and enjoy life (9:1–12:14) Continuing the book’s grand finale (11:9–12:7), Solomon transitions from the enjoyment of “seeing the sun” to the approach of death. Assuming temporal existence for mankind “under the sun,” “he broadens the range of his observation to include God, who is above the sun, and death, which is beyond the sun.”1 When the wise contemplate death, they find all aspirations to grandeur and gain exposed as illusory visions of their own arrogance. Brown says of such contemplation, that it “purges the soul of all futile striving and, paradoxically, anxiety. The eternal sleep of death serves as a wake-up call to live and welcome the serendipities of the present.”2 Just as the setting sun signals the end of a day, so aging signals the approach of the close of one’s life. Preparation for the end of life must begin even in youth. “Before” in verses 1, 2, and 6 sets up a time-oriented series of statements that favor understanding the text as a description of the time of death, rather than merely a depiction of the process of aging.3 The first seven verses of this chapter comprise one long sentence.4 If someone were to read it aloud as one sentence, he or she would be “‘out of breath’ by the end”5—a play on the key word hebel, which can also mean “breath,” as well as “vanity,” “futility,” or “fleeting.” However, the interpreter would be remiss to focus too much upon death in this section. -

Ecclesiastes 12 Do It Now As We Begin the Last Chapter of Ecclesiastes Let Me Remind You of the Four Major Points of the Last Tw

Ecclesiastes 12 Do It Now As we begin the last chapter of Ecclesiastes let me remind you of the four major points of the last two chapters: 1. Life is an adventure – live it by faith, 2. Life is a gift – enjoy it, 3. Life is a stewardship – live it for the glory of God and 4. Life is short – therefore serve God now. This is what the last chapter is all about, serve God, do it now, before it’s too late. We don’t serve God because He needs something from us. Acts 17 tells us that God is not served by our works as though he needed anything “since He gives to all life, breath and all things.”1 We serve God by loving Him and obeying Him and in return our lives are filled with His grace, power and love. Here in the last chapter of Ecclesiastes the call to serve God now is made specifically to young people. Someone has said that youth is for pleasure, middle age is for business and old age is for religion. That is a frightful delusion. We need to love and serve God now, for our own wellbeing, because tomorrow is never guaranteed. So let’s begin. Remember now your Creator in the days of your youth, Before the difficult days come, And the years draw near when you say, “I have no pleasure in them”: (Ecclesiastes 12:1) Remember your Creator. Think carefully about your Creator. Live in His presence daily. Seek to discover His greatness and glory now. -

![Commentary on Ecclesiastes 11:9-12:7, 13 [14] by L.G](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2509/commentary-on-ecclesiastes-11-9-12-7-13-14-by-l-g-1042509.webp)

Commentary on Ecclesiastes 11:9-12:7, 13 [14] by L.G

Commentary on Ecclesiastes 11:9-12:7, 13 [14] By L.G. Parkhurst, Jr. The International Bible Lesson (Uniform Sunday School Series) for Sunday, October 16, 2011, is from Ecclesiastes 11:9-12:7, 13. Five Questions for Discussion and Thinking Further follow the Bible Lesson Commentary below. Study Hints for Thinking Further, which are also available on the Bible Lesson Forum, will aid teachers in conducting class discussion. Ecclesiastes 11:9-12:7, 13 [14] (Ecclesiastes 11:9) Rejoice, young man, while you are young, and let your heart cheer you in the days of your youth. Follow the inclination of your heart and the desire of your eyes, but know that for all these things God will bring you into judgment. Solomon’s book tells young people to enjoy being young while they can, for they will soon be old. He also tells young people the choice before them. They can do what they want (set their own goals and follow their feelings) or they can “keep God’s commandments” (see Ecclesiastes 12:13). If they obey or disobey God when following their feelings or setting their own goals, then God will judge whether their choices and actions are right or wrong, good or evil (see Ecclesiastes 12:14). God will hold everyone accountable and responsible for their way of life. (Ecclesiastes 11:10) Banish anxiety from your mind, and put away pain from your body; for youth and the dawn of life are vanity. The “dawn of life” (meaning “infancy and childhood”) and youth are vanity or meaningless depending on what a child or youth plans to do and what actions they take.