SHASTA REPORT Final Cannon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mainstem Klamath River Fall Chinook Salmon Redd Survey 2012

1,839U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Arcata Fisheries Data Series Report DS 2014-39 Mainstem Klamath River Fall Chinook Salmon Redd Survey 2012 Mark Magneson and Philip Colombano U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Arcata Fish and Wildlife Office 1655 Heindon Road Arcata, CA 95521 (707) 882-7201 November 2014 Disclaimers Funding for this study was provided by the Klamath River Habitat Assessment Study administered by the Arcata Fish and Wildlife Office. Disclaimer: The mention of trade names or commercial products in this report does not constitute endorsement or recommendation for use by the Federal government. The Arcata Fish and Wildlife Office Fisheries Program reports its study findings through two publication series. The Arcata Fisheries Data Series was established to provide timely dissemination of data to local managers and for inclusion in agency databases. The Arcata Fisheries Technical Reports publishes scientific findings from single and multi-year studies that have undergone more extensive peer review and statistical testing. Additionally, some study results are published in a variety of professional fisheries journals. Key words: Chinook salmon, Klamath River, redd, escapement, spawning survey. The correct citation for this report is: Magneson, M.D., and P. Colombano. 2014. Mainstem Klamath River Fall Chinook Salmon Redd Survey 2012. U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Arcata Fish and Wildlife Office, Arcata Fisheries Data Series Report Number DS 2014-39, Arcata, California. ii Table of Contents page Introduction ........................................................................................................................ -

UKTR Chinook Biological Review Team

Upper Klamath and Trinity River Chinook Salmon Biological Review Team Report Williams1, T. H., J. C. Garza1, N. Hetrick2, S. T. Lindley1, M. S. Mohr1, J. M. Myers3, M. R. O’Farrell1, R. M. Quiñones4, and D. J. Teel3 1 National Marine Fisheries Service, Southwest Fisheries Science Center, Santa Cruz, California. 2 U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Arcata Fish and Wildlife Office, Arcata, California. 3 National Marine Fisheries Service, Northwest Fisheries Science Center, Seattle, Washington. 4 U.S. Forest Service, Klamath National Forest, Yreka, California. December 2011 ii Table of Contents List of Figures.................................................................................................................... iv List of Tables ...................................................................................................................... v 1. Background..................................................................................................................... 1 2. ESU Configuration.......................................................................................................... 2 3. Biological Status of Upper Klamath and Trinity River Chinook Salmon ESU............ 11 4. Conclusions................................................................................................................... 25 5. References..................................................................................................................... 27 iii List of Figures Figure 1. Two generalized patterns of evolution of life-history -

Estimation of Stream Conditions in Tributaries of the Klamath River, Northern California

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Arcata Fisheries Technical Report TR 2018-32 Estimation of Stream Conditions in Tributaries of the Klamath River, Northern California Christopher V. Manhard, Nicholas A. Som, Edward C. Jones, Russell W. Perry U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Arcata Fish and Wildlife Office 1655 Heindon Road Arcata, CA 95521 (707) 822-7201 January 2018 Funding for this study was provided by a variety of sources including the Klamath River Fish Habitat Assessment Program administered by the Arcata Fish and Wildlife Office, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and the Bureau of Reclamation, Klamath Falls Area Office. Disclaimer: The mention of trade names or commercial products in this report does not constitute endorsement or recommendation for use by the Federal Government. The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. The Arcata Fish and Wildlife Office Fisheries Program reports its study findings through two publication series. The Arcata Fisheries Data Series was established to provide timely dissemination of data to local managers and for inclusion in agency databases. Arcata Fisheries Technical Reports publish scientific findings from single and multi- year studies that have undergone more extensive peer review and statistical testing. Additionally, some study results are published in a variety of professional fisheries aquatic habitat conservation journals. To ensure consistency with Service policy relating to its online peer-reviewed journals, Arcata Fisheries Data Series and Technical Reports are distributed electronically and made available in the public domain. Paper copies are no longer circulated. -

Klamath River Hydroelectric Settlement Agreement Interim Measure 15

Klamath River Hydroelectric Settlement Agreement Interim Measure 15: Final 2019 Water Quality Monitoring Study Plan Prepared: January 16, 2019 KHSA IM15 2019 STUDY PLAN Table of Contents 1. Introduction and Overview ............................................................................................. 1 2. Objectives ....................................................................................................................... 3 3. Monitoring Components ................................................................................................. 4 3.1 Public Health Monitoring of Cyanobacteria and Toxins .......................................... 4 3.2 Baseline Water Quality Monitoring of the Klamath River ....................................... 4 4. Quality Assurance, Data Management, and Dissemination ............................................ 5 4.1 KHSA Program Quality Assurance Strategy for 2019 ............................................. 5 5. Sampling Constituents and Frequency............................................................................ 7 5.1 Public Health Monitoring of Cyanobacteria and Toxins .......................................... 7 5.2 Comprehensive Baseline Water Quality Monitoring of the Klamath River ............. 9 6.0 References ................................................................................................................... 13 List of Figures Figure 1. 2019 KHSA IM 15 monitoring stations .............................................................. 2 List of Tables -

Little Shasta River 2017-2019: Pre-Project Assessment of the Proposition 1 Ecosystem Restoration Grant Activities

Little Shasta River 2017-2019: Pre-Project Assessment of the Proposition 1 Ecosystem Restoration Grant Activities Authors: Amber Lukk, Priscilla Vasquez-Housley, Robert Lusardi, Ann Willis Report prepared for: California Trout and California Wildlife Conservation Board December 2019 Contents Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 1 Study Area ...................................................................................................................................... 1 Methods........................................................................................................................................... 4 Hydrologic Year Type ................................................................................................................. 4 Discharge ..................................................................................................................................... 4 Water Temperature ...................................................................................................................... 5 Water Quality .............................................................................................................................. 5 Aquatic Macroinvertebrates ........................................................................................................ 6 Fish Presence/Absence ............................................................................................................... -

Klamath River Fall Chinook Salmon Age-Specific Escapement, River Harvest, and Run Size Estimates, 2020 Run

1 Klamath River Fall Chinook Salmon Age-Specific Escapement, River Harvest, and Run Size Estimates, 2020 Run Klamath River Technical Team 15 February 2021 Summary The number of Klamath River fall Chinook Salmon returning to the Klamath River Basin (Basin) in 2020 was estimated to be: Run Size Age Number Proportion 2 9,077 0.17 3 37,820 0.69 4 7,579 0.14 5 8 0.00 Total 54,484 1.00 Preseason forecasts of the number of fall Chinook Salmon adults returning to the Basin and the corresponding post-season estimates are: Adults Preseason Postseason Sector Forecast Estimate Pre / Post Run Size 59,100 45,400 1.30 Fishery Mortality Tribal Harvest 8,600 5,200 1.65 Recreational Harvest 1,300 5,100 0.25 Drop-off Mortality 800 600 1.33 10,700 10,900 0.98 Escapement Hatchery Spawners 12,200 8,300 1.47 Natural Area Spawners 36,200 26,200 1.38 48,400 34,500 1.40 2 Introduction This report describes the data and methods used by the Klamath River Technical Team (KRTT) to estimate age-specific numbers of fall Chinook Salmon returning to the Basin in 2020. The estimates provided in this report are consistent with the Klamath Basin Megatable (CDFW 2021) and with the 2021 forecast of ocean stock abundance (KRTT 2021). Age-specific escapement estimates for 2020 and previous years, coupled with the coded-wire tag (CWT) recovery data from Basin hatchery stocks, allow for a cohort reconstruction of the hatchery and natural components of Klamath River fall Chinook Salmon (Goldwasser et al. -

The Nelson Ranch Located Along the Shasta River Has Two Flow Gaging

Baseline Assessment of Salmonid Habitat and Aquatic Ecology of the Nelson Ranch, Shasta River, California Water Year 2007 Jeffrey Mount, Peter Moyle, and Michael Deas, Principal Investigators Report prepared by: Carson Jeffres (Project lead), Evan Buckland, Bruce Hammock, Joseph Kiernan, Aaron King, Nickilou Krigbaum, Andrew Nichols, Sarah Null Report prepared for: United States Bureau of Reclamation Klamath Area Office Center for Watershed Sciences University of California, Davis • One Shields Avenue • Davis, CA 95616-8527 Table of Contents 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY..................................................................................................................................2 2. INTRODUCTION...............................................................................................................................................6 3. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS .................................................................................................................................6 4. SITE DESCRIPTION.........................................................................................................................................7 5. HYDROLOGY.....................................................................................................................................................8 5.1. STAGE-DISCHARGE RATING CURVES .......................................................................................................9 5.2. PRECIPITATION........................................................................................................................................11 -

Yurok Final Brief

Case 3:16-cv-06863-WHO Document 107 Filed 03/23/18 Page 1 of 22 JEFFREY H. WOOD, Acting Assistant Attorney General 1 Environment & Natural Resources Division 2 SETH M. BARSKY, Chief S. JAY GOVINDAN, Assistant Chief 3 ROBERT P. WILLIAMS, Sr. Trial Attorney KAITLYN POIRIER, Trial Attorney 4 U.S. Department of Justice 5 Environment & Natural Resources Division Wildlife & Marine Resources Section 6 Ben Franklin Station, P.O. Box 7611 7 Washington, D.C. 20044-7611 Tel: 202-307-6623; Fax: 202-305-0275 8 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] 9 10 Attorneys for Federal Defendants 11 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT 12 FOR THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA 13 SAN FRANCISCO DIVISION 14 YUROK TRIBE, et al., ) 15 Case No. 3:16-cv-06863-WHO ) 16 Plaintiff, ) ) 17 FEDERAL DEFENDANTS’ RESPONSE v. ) TO DEFENDANT-INTERVENORS’ 18 ) MOTION FOR RELIEF FROM U.S. BUREAU OF RECLAMATION, et al., ) JUDGMENT AND/OR STAY OF 19 ) ENFORCEMENT (ECF No. 101) Defendants, ) 20 ) 21 and ) ) 22 KLAMATH WATER USERS ) ASSOCIATION, et al., ) 23 ) 24 Defendant-Intervenors. ) 25 26 27 28 1 Federal Defendants’ Response to Intervenors’ Motion for Relief 3:16-cv-6863-WHO Case 3:16-cv-06863-WHO Document 107 Filed 03/23/18 Page 2 of 22 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS 2 I. INTRODUCTION 3 3 II. FACTUAL BACKGROUND 5 4 A. Hydrologic Conditions In Water Year 2018 5 5 B. 2013 Biological Opinion Requirements for Suckers 5 6 III. DISCUSSION 7 7 A. Given Hydrologic Conditions, Guidance Measures 1 8 and 4 Cannot Both Be Implemented As They Were Designed Without Impermissibly Interfering With 9 Conditions Necessary to Protect Endangered Suckers 7 10 1. -

Shasta River Chinook and Coho Salmon Observations in 2013 Siskiyou County, CA

California Department of Fish and Wildlife Final Report Klamath River Project August 14, 2014 Shasta River Chinook and Coho Salmon Observations in 2013 Siskiyou County, CA Prepared by: Diana Chesney and Morgan Knechtle California Department of Fish and Wildlife Klamath River Project 1625 S. Main Street Yreka, CA 96097 (530) 841-1176 1 California Department of Fish and Wildlife Final Report Klamath River Project August 14, 2014 Shasta River Fish Counting Facility, Chinook and Coho Salmon Observations in 2013 Siskiyou County, CA ABSTRACT A total of 8,021 fall run Chinook salmon (Chinook, Oncorhynchus tshawytscha) were estimated to have entered the Shasta River during the 2013 spawning season. An underwater video camera was operated in the flume of the Shasta River Fish Counting Facility (SRFCF) twenty four hours a day, seven days a week, from August 28, 2013 until December 9, 2013, when the weir sustained structural damage from ice build-up and was removed. The first Chinook was observed on September 9, 2013 and the last Chinook on December 3, 2013. KRP staff also processed a total of 512 Chinook carcasses during spawning ground surveys (of which 469 were used in fork length histograms), 65 Chinook carcasses as wash backs against the SRFCF weir (a systematic 1:10 sample), and 45 live Chinook in a trap immediately upstream of the video flume during the season. Chinook carcasses sampled in the spawning ground surveys ranged in fork length (FL) from 43 cm to 100 cm and grilse were determined to be < 59 cm in FL. Males ranged in FL from 43 to100 cm. -

Schedule of Proposed Action (SOPA) 10/01/2020 to 12/31/2020 Klamath National Forest This Report Contains the Best Available Information at the Time of Publication

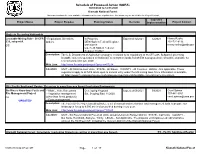

Schedule of Proposed Action (SOPA) 10/01/2020 to 12/31/2020 Klamath National Forest This report contains the best available information at the time of publication. Questions may be directed to the Project Contact. Expected Project Name Project Purpose Planning Status Decision Implementation Project Contact Projects Occurring Nationwide Locatable Mining Rule - 36 CFR - Regulations, Directives, In Progress: Expected:12/2021 12/2021 Nancy Rusho 228, subpart A. Orders DEIS NOA in Federal Register 202-731-9196 EIS 09/13/2018 [email protected] Est. FEIS NOA in Federal Register 11/2021 Description: The U.S. Department of Agriculture proposes revisions to its regulations at 36 CFR 228, Subpart A governing locatable minerals operations on National Forest System lands.A draft EIS & proposed rule should be available for review/comment in late 2020 Web Link: http://www.fs.usda.gov/project/?project=57214 Location: UNIT - All Districts-level Units. STATE - All States. COUNTY - All Counties. LEGAL - Not Applicable. These regulations apply to all NFS lands open to mineral entry under the US mining laws. More Information is available at: https://www.fs.usda.gov/science-technology/geology/minerals/locatable-minerals/current-revisions. R5 - Pacific Southwest Region, Occurring in more than one Forest (excluding Regionwide) Six Rivers Hazardous Fuels and - Wildlife, Fish, Rare plants Developing Proposal Expected:06/2021 09/2021 Carol Spinos Fire Management Project - Vegetation management Est. Scoping Start 11/2020 707-441-3561 EA (other than forest products) [email protected] *UPDATED* - Fuels management Description: The Fuels & Fire Project would authorize a set of manual and mechanical land management tools to prepare our landscapes for up to 8,000 acres of prescribed burning every year. -

Klamath River Fall Chinook Salmon Age-Specific Escapement, River Harvest, and Run Size Estimates, 2018 Run

Klamath River Fall Chinook Salmon Age-Specific Escapement, River Harvest, and Run Size Estimates, 2018 Run Klamath River Technical Team 14 February 2019 Summary The number of Klamath River fall Chinook Salmon returning to the Klamath River Basin (Basin) in 2018 was estimated to be: Run Size Age Number Proportion 2 11,114 0.11 3 86,717 0.84 4 5,567 0.05 5 9 0.00 Total 103,407 1.00 Preseason forecasts of the number of fall Chinook Salmon adults returning to the Basin and the corresponding post-season estimates are: Adults Preseason Postseason Sector Forecast Estimate Pre / Post Run Size 91,900 92,300 1.00 Fishery Mortality Tribal Harvest 18,100 14,800 1.22 Recreational Harvest 3,500 4,100 0.85 Drop-off Mortality 1,600 1,300 1.23 23,200 20,200 1.15 Escapement Hatchery Spawners 27,900 18,600 1.50 Natural Area Spawners 40,700 53,600 0.76 68,600 72,200 0.95 Introduction This report describes the data and methods used by the Klamath River Technical Team (KRTT) to estimate age-specific numbers of fall Chinook Salmon returning to the Basin in 2018. The estimates provided in this report are consistent with the Klamath Basin Megatable (CDFW 2019) and with the 2019 forecast of ocean stock abundance (KRTT 2019). Age-specific escapement estimates for 2018 and previous years, coupled with the coded-wire tag (CWT) recovery data from Basin hatchery stocks, allow for a cohort reconstruction of the hatchery and natural components of Klamath River fall Chinook Salmon (Goldwasser et al. -

Ef and Ffects O Consid of Dwin Deration Nell Da Ns for P Am on S

Effects of Dwinnell Dam on Shasta River Salmon and Considerations for Prioritizing Recovery Actions March 2012 Submitted to Karuk Tribe Happy Camp, CCA Prepared by Larry Lestelle 17791 Fjord Drive NE Suite AA Poulsbo, WA 98370 360-697-6702 Executive Summary This executive summary covers only key portions of some of the report sections for the sake of brevity. Introduction This document provides the Karuk Tribal Council an assessment of the effects of Dwinnell Dam on the salmon resources of the Shasta River and gives my perspectives for prioritizing possible recovery actions in the subbasin, including dam removal. It is a companion document to one prepared by Tom Cannon that reviews alternatives for achieving salmon recovery objectives associated with a dam removal scenario (Cannon 2011). The focus of this report is on the Pacific salmon species Chinook and coho, which are indigenous to the Shasta River subbasin. Coho in the Klamath River Basin, as part of the Southern Oregon Northern California Coasts evolutionary significant unit (SONCC Coho ESU), were listed in 1997 as threatened under the Endangered Species Act (ESA). The Shasta River is one of the most unique river systems anywhere in the Pacific Northwest and Northern California. Historically, it is believed that it was an extremely productive salmon river because of its flow, thermal, and nutrient characteristics. But the story of the Shasta River is similar to many salmon rivers in the west—it has been heavily altered by human development and its salmon populations have suffered huge losses. Similarly, there is hope that salmon can once again thrive in the Shasta River if restoration actions can be sufficiently implemented.