CLASS and SOCIETY

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2017 Courses at Wellesley and Workshops

EXPLORE THE WORLD OF PEOPLE AND IDEAS Zombinomics Pandemic! Outbreak! Go! Post-Apocalyptic Economics Bacterial Epidemiology E-20 Summit Fix It + Flip It Crime Squad So, You Want to Be a Doctor? World Economics Interior Remodeling Design Criminal Investigations Medical Careers THIS GUIDE IS FOR REFERENCE ONLY Cupcake Armada Processing Makes Perfect Perfect Pixels Flying Ninjas Cupcake ChallengesThe coursesComputer and Programming workshops listedIntro toin Digital this Photography guide were offeredAerial Robotics during the summer of 2017. While we will offer a similar range of courses and workshops in 2018, specific options may change. 2018 options will be published later in the fall. Sing It? Bring It! The Wig + the Wardrobe Pigskin Payoff Accessorize This! Pop Choir Music Costume, Hair + Make-up Design Business of Sports Intro to Accessory Design Sky Scraping Race on Mars! Manufacturing Mario Cooks Unhooked Commercial Architecture Exploratory Robotics Conceptual Video Game Design Cooking Challenges 2017 Courses and Workshops at Wellesley EXPLO 360 at Wellesley: Courses Summer 2017 EXPLORE THE WORLD OF PEOPLE AND IDEAS… AND DISCOVER YOUR PLACE IN IT Step out of your comfort zone and explore the world of people and ideas. Whether you’re an expert in algebra, basketball, or ceramics, – or whether you’ve only imagined being a fashion Curriculum Innovation designer, a sports agent, or a crime scene scientist, – EXPLO lets at EXPLO you dive into what you love as well as what you dream about. The choice is all yours. Our curriculum team spends 10 months a year The courses and workshops at EXPLO 360 at Wellesley are your planning and preparing opportunity to develop and express your natural talents or explore new the hundreds of courses interests and skills in a pressure-free environment (That’s right — and workshops that EXPLO no grades!) with other students offers each summer. -

Primates Don't Make Good Pets! Says Lincoln Park

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE EDITOR’S NOTE: Photos of an appropriate multi-male, multi-female group of chimpanzees at Lincoln Park Zoo can be found HERE. Pet trade images are not shared as Lincoln Park Zoo research shows when these images of chimpanzees in human settings are circulated, chimpanzees are not believed to be endangered. Primates Don’t Make Good Pets! Says Lincoln Park Zoo Series of manuscripts from the Lester E. Fisher Center for the Study and Conservation of Apes bring light to the detrimental effects of atypically-housed chimpanzees Chicago (December 13, 2017) – The Wolf of Wall Street movie. Weezer’s “Island in the Sun” music video. Michael Jackson’s “pet” Bubbles. While these may seem like unrelated pop culture references, they all have a similarly daunting theme: the use of chimpanzees in the pet or entertainment trade. These chimpanzees typically are raised by humans and rarely see others of their own species until they are fortunate enough to be moved to an accredited zoo or sanctuary. For years, Lincoln Park Zoo researchers have documented the long-term effects of this unusual human exposure on chimpanzees. Now, a third and final study in a series has been published in Royal Society Open Science Dec. 13 showcasing the high stress levels experienced by these chimpanzees who have been raised in human homes and trained to perform for amusement. Over the course of the three years, Fisher Center researchers evaluated more than 60 chimpanzees – all now living in accredited zoos and sanctuaries - and examined the degree to which they were exposed to humans and to their own species over their lifetime to determine the long-term effects of such exposure. -

Artist: Period/Style: Patron: Material/Technique: Form

TITLE:Vietnam Veterans Memorial LOCATION: Washington, D.C., U.S. DATE: . 1982 C.E. ARTIST: Maya Lin PERIOD/STYLE: Minimalism PATRON: The Commision of Fine Arts MATERIAL/TECHNIQUE: Granite FORM: Highly reflective black granite with incised names of 58,000 names ofVietnam Veterans who sacrificed their lives during the conflict. The name is an abstraction that means more to the family and friends than a pictorial representation. The two walls start very short and get progressively taller until they meet at an oblique angle at the monument’s center. One wall points towards the Washington Monument; the other points to the Lincoln Memorial. FUNCTION: It functions as a memorial to the soldiers that died during the Vietnam War. It is an ideal place for people to come and spend quiet time reflecting on the names and perhaps leaving mementos to the deceased. CONTENT: The walls are made of a dark igneous rock called gabbro, a type of granite, which is highly reflective when polished.The surface of the monument is etched with the 58,195 names of the Americans who died or remained missing in action in the Vietnam War. The names are listed in the order in which they were reported killed or missing in action. This makes the names harder to find, and re- quires a listing and numeric system of organization for visitors. CONTEXT: There were 1400 anonymous entries for this commission. There was a real backlash once her identity was known because of latent racism in the post Vietnam era. She defended her design in front of the United States Congress, who eventually reached a compro- mise: A group of more “traditional” sculptures, called “The Three Soldiers,” was erected near the monument. -

![[Brand × Artist] Collaborations](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2226/brand-%C3%97-artist-collaborations-662226.webp)

[Brand × Artist] Collaborations

FROM HIGH ART TO HIGH TOPS : THE IMPACT OF [ BRAND × ARTIST ] COLLABORATIONS WORD S A NYA FIRESTO N E On the world-map of today’s creative brands, we increasingly find Margiela. That art is being called upon as branding’s new muse, and collaborations with art — contemporary or otherwise — where × signifies a drive to create something more complex than that which marks the spot: can be achieved through fashion. It is logical that this nouveau artistic collaborative wave hits hard Don Perignon × Jeff Koons today, an epoch when magic is no longer required to see almost Perrier × Andy Warhol anything and everything thanks to the world’s new beloved fairy Supreme × Damien Hirst godmother: #socialmedia. With the advent of digital platforms comes Raf Simons × Sterling Ruby the collective impulse to display not only a style, but perhaps more COMME des GARÇONS × Ai Weiwei importantly, lifestyle. Look at any creative company’s Instagram and Lacoste × Zaha Hadid we find not only pictures of its gadgets and gizmos, but a cultivated Opening Ceremony × René Magritte existence around them — tastes and sensibilities, filtered through adidas × Jeremy Scott “Keith Harring” specific lenses: urban landscapes, graffiti, perfectly frothed lattes, Pharell’s hat, Kanye’s pout, and various other facades of society And so the formula of [Brand by Artist] is written, etched onto that visually amalgamate to project a brand’s metaphysical culture skateboards and sneakers, from H&M to Hermés, on Perignon to in time and space. Perrier, strutting down catwalks and stacking grocery aisles at a prolific It is no wonder then why brands are increasingly seduced by art; rate. -

Michael Jackson Betwixt and Between: the Construction of Identity in 'Leave Me Alone' (1989)

Contents Introduction 2 Chapter 1: Literature Review 4 1.1: Past Research: On Michael Jackson Studies 4 1.2: Disability Studies 4 1.2.1: The Static Freak/Plastic Freak 6 1.3: Defining the Liminal 7 1.4: Postmodern Theory: The Social Construction of Identity 8 Chapter 2: Methodology 10 Chapter 3: Analysis 12 3.1: Narrative Structure of ‘Leave Me Alone’ 12 3.2: Media Narratives in ‘Leave Me Alone’ 13 3.3: The Static Freak/Plastic Freak in ‘Leave Me Alone’ 15 3.4: Liminal Identity: Temporary Phase/Permanent Place 16 3.5: Postmodern Subjects: The Aesthetics of the Collage 17 3.6: Identity and Postmodernism: The Problem With Disability Studies 18 Chapter 4: Conclusion 20 Bibliography 22 Attachment 1: Images 24 Attachment 2: Shotlist ‘Leave Me Alone’ 27 1 Introduction ‘The bottom line is they don’t know and everyone is going to continue searching to find out whether I’m gay, straight, or whatever … And the longer it takes to discover this, the more famous I will be.’1 * * * ‘Michael’s space-age diet’, ‘Bubbles the chimp bares all about Michael’, ‘Michael proposes to Liz’, ‘Michael to marry Brooke’. These may look like part of the usual rumors about Jackson frequently appearing in the media, however, they are not. Instead, these headlines are the opening scene of the music video for Jackson’s song ‘Leave Me Alone’, released on January 2, 1989, and directed by Jim Blashfield. Jackson opens by singing the words: I don't care what you talkin' 'bout baby I don't care what you say Don't you come walkin' beggin' back mama I don't care anyway ‘Leave Me Alone’ is a response to the rumors that began to circulate in the media after the worldwide success of Jackson’s 1982 album Thriller. -

Honors Curriculum Sheet

Honors Program Course Offerings, Updated as of 8/14/2020 Fall Quarter, 2020-2021 Course Day/Time Instructor HON 101 - World Forbidden Knowledge Wed: Mark Arendt Literature Are there limits to what we should know? From Chaucer, in The Wife of 11:20AM-12:50PM Bath’s Tale, “Forbede us thing and That desiren we,” to Lou Reed’s Modality: Transformer album, “Hey babe, take a walk on the wild side,” literature is Online-Hybrid replete with transgressors and transgressions. In this course students will study the subject of forbidden knowledge as it is expressed in classic and contemporary works of fiction, poetry and drama – from portions of Milton’s Paradise Lost to Denis Johnson’s Jesus’ Son and Mary Gaitskill’s Bad Behavior. HON 101 - World Masterpieces of Japanese Women Tues/Thurs: Heather Bowen-Struyk Literature This course begins over 1000 years ago with masterpieces of world 1:00PM-2:30PM literature. In contrast to other national literary canons, the great works of Modality: classical Japan were written by women in the imperial court. In this course, Online-Sync we will travel the socio-historical distance from the women of classical court literature to Raichō and her coterie of bluestocking feminists and beyond, to our own time, with a self-reflexive novel by Japanese-Canadian Buddhist Ruth Ozeki. Through readings of poetry, diaries, and fiction, this course offers an introduction to important issues for discussing literature including gender and sex, class and labor, ethnicity and race, and diaspora and national identity. HON 102: History in The Arabian Nights in World History Wednesday: Warren Schultz Global Contexts Chances are we have all heard of Aladdin, Ali Baba, Genies, and Sinbad the 9:40AM-11:10AM Sailor, but how well do we really know them? This course explores the Modality: history of the famous collection of tales from which these characters are Online-Hybrid commonly assumed to have inhabited, the Book of the Thousand and One Nights. -

PICASSO: Mosqueteros

G A G O S I A N G A L L E R Y February 14, 2009 PRESS RELEASE GAGOSIAN GALLERY 522 WEST 21ST STREET T. 212.741.1717 NEW YORK, NY 10011 F. 212.741.0006 GALLERY HOURS: Mon – Sat: 10:00am– 6:00pm PICASSO: Mosqueteros Thursday, March 26 – Saturday, June 6, 2009 Opening reception: Thursday, March 26th, from 6 to 8pm I enjoy myself to no end inventing these stories. I spend hour after hour while I draw, observing my creatures and thinking about the mad things they're up to. --Pablo Picasso, 1968 “Picasso: Mosqueteros” is the first exhibition in the United States to focus on the late paintings since “Picasso: The Last Years: 1963-1973” at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in 1984. Organized around a large group of important, rarely seen works from the collection of Bernard Ruiz-Picasso, as well as works from The Museum of Modern Art, New York, the Museo Picasso Málaga and other private collections, “Picasso: Mosqueteros” aims to expand the ongoing inquiry regarding the context, subjects, and sources of the artist’s late work. Building on new research into the artist’s late life through the presentation of selected paintings and prints spanning 1962-1972, the exhibition suggests how the portrayal of the aged Picasso, bound to the past in his life and painting, has obscured the highly innovative and contemporary nature of the late work. The tertulia, an Iberian tradition of gregarious social gatherings with literary or artistic overtones, played a major part in Picasso’s everyday life, even after he moved to the relative seclusion of Notre-Dame-de-Vie in the 1960s. -

98.6: a Creative Commonality

CONTENT 1 - 2 exibition statement 3 - 18 about the chimpanzees and orangutans 19 resources 20 educational activity 21-22 behind the scenes 23 installation images 24 walkthrough video / flickr page 25-27 works in show 28 thank you EXHIBITION STATEMENT Humans and chimpanzees share 98.6% of the same DNA. Both species have forward-facing eyes, opposing thumbs that accompany grasping fingers, and the ability to walk upright. Far greater than just the physical similarities, both species have large brains capable of exhibiting great intelligence as well as an incredible emotional range. Chimpanzees form tight social bonds, especially between mothers and children, create tools to assist with eating and express joy by hugging and kissing one another. Over 1,000,000 chimpanzees roamed the tropical rain forests of Africa just a century ago. Now listed as endangered, less than 300,000 exist in the wild because of poaching, the illegal pet trade and habitat loss due to human encroachment. Often, chimpanzees are killed, leaving orphans that are traded and sold around the world. Thanks to accredited zoos and sanctuaries across the globe, strong conservation efforts and programs exist to protect and manage populations of many species of the animal kingdom, including the great apes - the chimpanzee, gorilla, orangutan and bonobo. In the United States, institutions such as the Association of Zoos and Aquariums (AZA) and the Species Survival Plan (SSP) work together across the nation in a cooperative effort to promote population growth and ensure the utmost care and conditions for all species. Included in the daily programs for many species is what’s commonly known as “enrichment”–– an activity created and employed to stimulate and pose a challenge, such as hiding food and treats throughout an enclosure that requires a search for food, sometimes with a problem-solving component. -

Jeff Koons Loses French Lawsuit Over ‘Slavish Copy’ of Naf Naf Advert US Artist Ordered to Pay Damages and Costs, but Fair D’Hiver Sculpture Escapes Seizure

AiA Art News-service Jeff Koons loses French lawsuit over ‘slavish copy’ of Naf Naf advert US artist ordered to pay damages and costs, but Fair d’Hiver sculpture escapes seizure ANNA SANSOM 9th November 2018 13:58 GMT Fait D'Hiver (1988) by Jeff Koons, on show at the Liebighaus museum on in Frankfurt in 2012 © Ralph Orlowski/Getty Images Jeff Koons has been found guilty of plagiarising a 1980s advertising campaign for French fashion brand Naf Naf to make his porcelain sculpture Fait d'Hiver (1988), which is part of his Banality series. The high court of Paris has ordered the artist’s company Jeff Koons LLC, and the Centre Pompidou, which exhibited the piece in a 2014 Koons exhibition, to pay Franck Davidovici, the creative director of Naf Naf, €135,000 in damages and interest, and €70,000 in trial costs. The court ruled that Jeff Koons LLC had counterfeited a 1985 Naf Naf advert, featuring a pig with a barrel of rum tied round its neck rescuing a girl in the snow, by using its “original elements”. Davidovici had sued for copyright infringement, with his lawyer, Jean Aittouares of Ox Avocats, describing the Koons sculpture as a “slavish copy” of the advert. “The court dismisses the argument of freedom of artistic expression, considering that Koons had clearly sought, by retaking the first work, to make 'the economy of a creative work',” Ox Avocats posted in a short online statement. The court also ordered Koons' company to pay €11,000 to Davidovici for reproducing an image of the sculpture on Koons' website, and €2,000 to Flammarion, the French publishing house, for reproducing an image of the work in the Centre Pompidou's exhibition catalogue. -

For Musicians

THE ULTIMATE GUIDE FOR MUSICIANS TURN YOUR YOUTUBE CHANNEL INTO A PROMOTION ENGINE THAT MAKES YOU MONEY THE ULTIMATE YOUTUBE PROMOTION GUIDE FOR MUSICIANS: How to Turn Your YouTube Channel Into an Engine That Makes You Money CONTENTS YouTube: home to cute cats, inane The Beginner’s Glossary of Basic memes, and the most revolutionary YouTube Terminology music-discovery platform in history! YouTube is quickly becoming the world’s most popu- How to Make a YouTube Channel That lar search engine for music. Think about it: whenever Engages Your Audience and Encourages your friend recommends a new band, whenever you Music Sales have a craving to hear a rare oldie, whenever you want to see if a musician can put on a good live show, where 10 Kinds of Music Videos to Promote do you turn? YouTube. Your Music At least that’s where millions of people are turning every day. Promote Your Music with YouTube Playlists For today’s independent musician, having a strong video presence is practically a requirement for a Enhance Your Video with successful DIY music career. YouTube videos are YouTube Annotations easily accessible and easily shareable across blogs, websites, and social networks. But it’s not always clear 5 Tips to YouTube Promotion how a YouTube view translates into albums sales or concert attendance. This guide addresses some of those mysteries. Stream Your Songs — Every Single One! YouTube is one of the most effective music promotion Earn Money from Your Music Videos machines ever, and we want you to use it to its fullest. CD Baby has put together this guide to help you with Earn More Money from YouTube: Host a the nuts and bolts, from coming up with a great video Video Contest concept to collecting the check for your music’s usage on YouTube! 1 The Ultimate YouTube Promotion Guide for Musicians The Beginner’s Glossary of Basic what the annotations say and where, when, and how they YouTube Terminology appear (and disappear) while the video plays. -

Alice Cooper 2011.Pdf

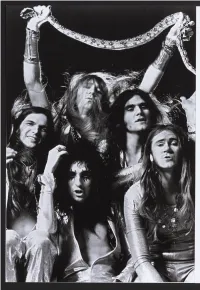

® • • • I ’ M - I N - T HE - MIDDLE-WIT HOUT ANT PLANS - I’M A BOY AND I’M-A MAN - I.’ M EIGHTEEN- - ® w Q < o ¡a 2 Ó z s * Tt > o ALICE M > z o g «< COOPER s [ BY BRAD T O L I N S K I ] y a n y standards, short years before, in 1967, Alice Cooper 1973 was an had been scorned as “the most hated exceptional year band” in Los Angeles. The group members for rock & roll. weirded out the locals by being the first Its twelve months hoys that weren’t transvestites to dress as saw the release girls, and their wildly dissonant, fuzzed- of such gems as out psychedelia sent even the most liberal Pink Floyd s The Dark Side of the Moon, hippies fleeing for the door. Any rational H H Led Zeppelin s Houses of the Holy, the human would have said they were 0 o W ho’s Quadrophenia, Stevie Wonders committing professional suicide, but z Innervisions, Elton Johns Goodbye Yellow the band members thought otherwise. Brick Road, and debuts from Lynyrd Who cared if a bunch o f Hollywood squares Skynyrd, Aerosmith, Queen, and the New thought they were gay? At least they Y ork D olls. were being noticed. But the most T H E BAND Every time they provocative and heard somebody audacious treasure G R A B B E D y e ll “faggot;” they of that banner year H EA D LIN ES AND swished more, and was Alice Coopers overnight they found £ o masterpiece, B illio n MADE WAVES fame as the group z w Dollar Babies, a it was hip to hate H m brilliant lampoon of American excess. -

The Two Favorite Recipes of Michael Jackson

The Two Favorite Recipes of Michael Jackson Stella and Phillip Lemarque Baba Rum International Publishing The Two Favorite Recipes of Michael Jackson © 2018 Stella and Phillip Lemarque All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in an form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the authors. Baba Rum International Publishing Los Angeles, California For more information or to contact the publisher visit bonjourneverland.com The essays in The Two Favorite Recipes of Michael Jackson are creative nonfiction. They are based on the authors’ true experiences but include dialog and fictional elements. Editorial and book design by Longhare Content & Editorial Services 2 The Two Favorite Recipes of Michael Jackson You are asking yourself, How does she know? Who is this—the cook! Yes, the cook. My name is Stella Lemarque. I created these dishes especially for Michael at Neverland, and here is my story. I grew up in Paris, the City of Lights—your typical Parisian girl. Yes, yes, in France we love our food. Food is a big part of the French culture. In my life, I have learned skills that have helped me cultivate a unique style of cooking. For a year, I worked at the side of one of the most famous chefs in the world, Roger Vergé, at his restaurant Le Moulin de Mougins. I was introduced to Provençȃle herbs, the cornerstone of French cuisine, which add myriad sparkles in your mouth. My time with Roger provided me with the knowledge to use the finest and freshest—and organic—ingredients to produce a plethora of pleasures during dining experiences.