Encounters with John Cage by Russell Hartenberger

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Compositional Procedures Used in John Cage's Six Short Inventions , First Construction (In Metal) , and Spontaneous Earth

THE COMPOSITIONAL PROCEDURES USED IN JOHN CAGE'S SIX SHORT INVENTIONS , FIRST CONSTRUCTION (IN METAL) , AND SPONTANEOUS EARTH Jesse James Guessford, D.M.A Department of Music University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2004 Sever Tipei, Advisor This study describes the processes that John Cage used in the composition of Six Short Inventions , First Construction (in Metal) , and Spontaneous Earth . With a lack of interest in John Cage’s early works, this study sheds light on the way in which these three early works are composed. In this study, the development of Cage’s square-root or micro-macrocosmic form is explored and then traced from the forms genesis to later modifications of the form. The centerpiece of the article is a description of the techniques used to create First Construction (in Metal) . Using Cage’s correspondence with Pierre Boulez as a starting point, the organizational tools and methods are uncovered and traced throughout the piece. Six Short Inventions is found to be an embryonic piece that holds traces of many of the techniques that come into existence in First Construction (in Metal) . Spontaneous Earth is used to follow the maturation of these techniques in Cage’s hands. © 2004 by Jesse James Guessford. All rights reserved THE COMPOSITIONAL PROCEDURES USED IN JOHN CAGE'S SIX SHORT INVENTIONS , FIRST CONSTRUCTION (IN METAL) , AND SPONTANEOUS EARTH BY JESSE JAMES GUESSFORD B.S., West Chester University, 1995 M.M., Potsdam College, State University of New York, 1997 DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in Music in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2004 Urbana, Illinois Abstract This study describes the processes that John Cage used in the composition of Six Short Inventions, First Construction (in Metal), and Spontaneous Earth. -

The William Paterson University Department of Music Presents New

The William Paterson University Department of Music presents New Music Series Peter Jarvis, director Featuring the Velez / Jarvis Duo, Judith Bettina & James Goldsworthy, Daniel Lippel and the William Paterson University Percussion Ensemble Monday, October 17, 2016, 7:00 PM Shea Center for the Performing Arts Program Mundus Canis (1997) George Crumb Five Humoresques for Guitar and Percussion 1. “Tammy” 2. “Fritzi” 3. “Heidel” 4. “Emma‐Jean” 5. “Yoda” Phonemena (1975) Milton Babbitt For Voice and Electronics Judith Bettina, voice Phonemena (1969) Milton Babbitt For Voice and Piano Judith Bettina, voice James Goldsworthy, Piano Penance Creek (2016) * Glen Velez For Frame Drums and Drum Set Glen Velez – Frame Drums Peter Jarvis – Drum Set Themes and Improvisations Peter Jarvis For open Ensemble Glen Velez & Peter Jarvis Controlled Improvisation Number 4, Opus 48 (2016) * Peter Jarvis For Frame Drums and Drum Set Glen Velez – Frame Drums Peter Jarvis – Drum Set Aria (1958) John Cage For a Voice of any Range Judith Bettina May Rain (1941) Lou Harrison For Soprano, Piano and Tam‐tam Elsa Gidlow Judith Bettina, James Goldsworthy, Peter Jarvis Ostinato Mezzo Forte, Opus 51 (2016) * Peter Jarvis For Percussion Band Evan Chertok, David Endean, Greg Fredric, Jesse Gerbasi Daniel Lucci, Elise Macloon Sean Dello Monaco – Drum Set * = World Premiere Program Notes Mundus Canis: George Crumb George Crumb’s Mundus Canis came about in 1997 when he wanted to write a solo guitar piece for his friend David Starobin that would be a musical homage to the lineage of Crumb family dogs. He explains, “It occurred to me that the feline species has been disproportionately memorialized in music and I wanted to help redress the balance.” Crumb calls the work “a suite of five canis humoresques” with a character study of each dog implied through the music. -

John Cage's Entanglement with the Ideas Of

JOHN CAGE’S ENTANGLEMENT WITH THE IDEAS OF COOMARASWAMY Edward James Crooks PhD University of York Music July 2011 John Cage’s Entanglement with the Ideas of Coomaraswamy by Edward Crooks Abstract The American composer John Cage was famous for the expansiveness of his thought. In particular, his borrowings from ‘Oriental philosophy’ have directed the critical and popular reception of his works. But what is the reality of such claims? In the twenty years since his death, Cage scholars have started to discover the significant gap between Cage’s presentation of theories he claimed he borrowed from India, China, and Japan, and the presentation of the same theories in the sources he referenced. The present study delves into the circumstances and contexts of Cage’s Asian influences, specifically as related to Cage’s borrowings from the British-Ceylonese art historian and metaphysician Ananda K. Coomaraswamy. In addition, Cage’s friendship with the Jungian mythologist Joseph Campbell is detailed, as are Cage’s borrowings from the theories of Jung. Particular attention is paid to the conservative ideology integral to the theories of all three thinkers. After a new analysis of the life and work of Coomaraswamy, the investigation focuses on the metaphysics of Coomaraswamy’s philosophy of art. The phrase ‘art is the imitation of nature in her manner of operation’ opens the doors to a wide- ranging exploration of the mimesis of intelligible and sensible forms. Comparing Coomaraswamy’s ‘Traditional’ idealism to Cage’s radical epistemological realism demonstrates the extent of the lack of congruity between the two thinkers. In a second chapter on Coomaraswamy, the extent of the differences between Cage and Coomaraswamy are revealed through investigating their differing approaches to rasa , the Renaissance, tradition, ‘art and life’, and museums. -

A Performer's Guide to the Prepared Piano of John Cage

A Performer’s Guide to the Prepared Piano of John Cage: The 1930s to 1950s. A document submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS in the Keyboard Studies Division of the College-Conservatory of Music By Sejeong Jeong B.M., Sookmyung Women’s University, 2011 M.M., Illinois State University, 2014 ________________________________ Committee Chair : Jeongwon Joe, Ph. D. ________________________________ Reader : Awadagin K.A. Pratt ________________________________ Reader : Christopher Segall, Ph. D. ABSTRACT John Cage is one of the most prominent American avant-garde composers of the twentieth century. As the first true pioneer of the “prepared piano,” Cage’s works challenge pianists with unconventional performance practices. In addition, his extended compositional techniques, such as chance operation and graphic notation, can be demanding for performers. The purpose of this study is to provide a performer’s guide for four prepared piano works from different points in the composer’s career: Bacchanale (1938), The Perilous Night (1944), 34'46.776" and 31'57.9864" For a Pianist (1954). This document will detail the concept of the prepared piano as defined by Cage and suggest an approach to these prepared piano works from the perspective of a performer. This document will examine Cage’s musical and philosophical influences from the 1930s to 1950s and identify the relationship between his own musical philosophy and prepared piano works. The study will also cover challenges and performance issues of prepared piano and will provide suggestions and solutions through performance interpretations. -

JOHN CAGE: the Works for Percussion 2

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Chicago-based percussion ensemble THIRD COAST PERCUSSION announces a new CD/DVD on MODE RECORDS JOHN CAGE: The Works for Percussion 2 A nation-wide release timed to honor Cage’s centenary year AVAILABLE MAY 22, 2012 "Percussion music is revolution. Sound and rhythm have too long been submissive to nineteenth-century music. Today we are fighting emancipation. Tomorrow, with electronic music in our ears, we will hear freedom.” – JOHN CAGE “Chops, polish and youthful joy in performing” “[One] of the city’s finest, hippest contemporary ensembles” - TIME OUT CHICAGO - THE CHICAGO TRIBUNE On May 22, 2012, the acclaimed Chicago-based percussion ensemble THIRD COAST PERCUSSION hails the centenary of the groundbreaking American artist JOHN CAGE with the release of its first full-length album, and its debut on MODE RECORDS: JOHN CAGE: The Works for Percussion 2 Third Construction (1941) Second Construction (1940) First Construction (1939) Trio (1936) Quartet (1935) Living Room Music (1940) available as both a CD and DVD In this album Third Coast Percussion offers passionate, immaculately prepared performances of works from John Cage’s early life; the years 1935-1941, when Cage was 23 to 29. It was during this time that Cage met and studied with Arnold Schoenberg and Henry Cowell, worked with Lou Harrison, fell in love with and married Xenia Andreyevna Kashevaroff, taught at UCLA, Mills College, the Cornish College of the Arts in Seattle, and the Chicago School of Design and found inspiration in Oskar Fischinger’s dictum that "everything in the world has a spirit that can be released through its sound,” among other adventures. -

Western Percussion Ensemble & World Percussion Ensemble Repertoire List

Western Percussion Ensemble & World Percussion Ensemble Repertoire List Selected Styles Studied and Performed by the World Percussion Ensemble Samba Batucada (Brazil) Samba Reggae (Brazil) Maracatu (Brazil) Pagode (Brazil) Various Styles of Condomblé (Brazil) Flamenco (Spain) Various Iqámat in Secular Styles (Middle East) Rumba - Guaguanco, Yambu, Columbia (Cuba) Bata (Cuba) Guiro (Cuba) Bembe (Cuba) Iyesa (Cuba) Batarumba (Cuba) Conga/Comparsa (Cuba) Dundunba (Guinea) Arara (Afro-Hatian) Selected Repertoire Performed by the Chamber Percussion Ensemble and Graduate Percussion Group (1999-2019): Keiko Abe Memories of the Seashore (ensemble version) Reflections on Japanese Children’s Songs III John Luther Adams Strange and Sacred Noise Green Corn Dance Dave Alcorn Four Miniatures III. Rondo Louis Andriessen Worker’s Union George Antheil Ballet Mécanique (1953 ed) Mark Applebaum Catfish Bob Becker Away Without Leave Mudra Noodrem Unseen Child Turning Point Cryin’ Time M. Benigno, A. Espere Ceci n'est pas une balle Warren Benson Three Pieces for Percussion Quartet John Bergamo The Grand Ambulation of the Bb Zombies Intentiions Johanna Beyer IV March Roger Braun A Terrible Beauty Independent Streams A Spirit Unbroken In the Pulse Michael Burritt Shadow Chasers The Doomsday Machine Matthew Burtner Mists John Cage Double Music First Construction in Metal Second Construction Third Construction Living Room Music Amores Trio Imaginary Landscape No. 2 Imaginary Landscape No. 3 Credo in US William Cahn Changes Six Pieces for Percussion Trio Carlos -

CAGE WAKES up JOYCE Recycling Through Finnegans Wake

CAGE WAKES UP JOYCE Recycling Through Finnegans Wake Ana Luísa Valdeira In the beginning was the word. I’ll begin with one: APPLE. Can you imagine one right now? Is it a red apple? Is it a green one? Does it smell of anything? Where is it? Is it on a tree? On a table? You can visualize any apple or any table. And each one of you will think diHerently, and not even two of you will create in your mind the same apple or the same table. That will never happen. Do you think the word APPLE appears in Finnegans Wake ? Those who have read it perhaps cannot remember very well because it is not a strange word, but I can tell you that the term, either alone or in the beginning, middle, or end of a diHerent word, appears around 30 times. Here are a few examples: Knock knock. War’s where! Which war? The Twwinns. Knock knock. Woos with- out! Without what? An apple. Knock knock. (Joyce 330.30-32) Broken Eggs will poursuive bitten Apples for where theirs is Will there’s his Wall; (Joyce 175.19-20) rhubarbarous maundarin yellagreen funkleblue windigut diodying applejack squeezed from sour grapefruice (Joyce 171.16-18) thought he weighed a new ton when there felled his first lapapple ; (Joyce 126.16-17) If my apple led you to very distinct pictures, I cannot even imagine how dif- ferent Joyce’s apples will be, judging by these examples. I believe that it will be harder for you to mentally draw them. -

10. John Cage Sonatas and Interludes for Prepared Piano: Sonatas I–III

10. John Cage Sonatas and Interludes for Prepared Piano: Sonatas I–III (For Unit 6: Further Musical Understanding) Background information and performance circumstances John Cage (1912-92) is now recognised as one of the most influential figures in twentieth- century music, although in his own time he was widely maligned and misunderstood, almost inevitably as he questioned so many of the fundamentals of western music. His principal achievements were to: ● develop the use of percussion ● exploit elements of chance and indeterminacy in performance ● explore new sound sources (including the prepared piano) ● use new forms of graphic notation ● be open to the influence of eastern philosophy on western art, both in his music and in his extensive writings. During the late 1930s, Cage moved towards composing music for percussion instruments. He considered rhythmic duration to be the most significant of the musical elements. Consequently, the system that Cage developed for giving rhythmic structure to music depended on using mathematical proportions to govern both the large-scale and small-scale dimensions of a work. Cage described his technique of rhythmic structure as ‘micro- macrocosmic’; it was first used significantly in the First Construction (in Metal), and then it dominated his compositions up to and beyond the Sonatas and Interludes. Composition for percussion and for modern dance led to the invention of the prepared piano. From the late 1930s, Cage was the musical director for a number of dance companies, eventually leading him to work for Merce Cunningham, who required him to write music to a predetermined number of beats, not necessarily organised or regular in terms of metrical schemes. -

AN EVENING of JOHN CAGE's PERCUSSION MUSIC at the MUSEUM of MODERN ART Friday and Saturday, August 12 and 13, 7:30 P.M

For Immediate Release August 1988 AN EVENING OF JOHN CAGE'S PERCUSSION MUSIC AT THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART Friday and Saturday, August 12 and 13, 7:30 p.m. Percussion music of John Cage is featured in the seventh SUMMERGARDEN program. In 1943 Cage conducted his first New York concert at The Museum of Modern Art. Included on that program was the then recent composition Amores--a suite of four pieces, two for the "prepared piano," which Cage invented, and two for percussion trio--and Credo in Us, which had been commissioned by Merce Cunningham. These two compositions will be heard in the all-Cage program on August 12 and 13. The complete program is as follows: John Cage, Credo in Us (1942) Second Construction (1940) Quartet (1935) Amores (1943) (in four movements) Inlets (1977) Imaginary Landscape No. 2 (1942) Among the more unusual instruments used in this program are: radio or phonograph (Credo in Us); tuned sleigh bells, wind glass, and thunder sheet (Second Construction); twelve conch shells, with a pre-recorded tape of burning - more - Friday and Saturday evenings in the Sculpture Garden of The Museum of Modern Art are made possible by a grant from Mobil i Tel: 212-708-9b . x: 62370 M - 2 - pine cones (Inlets); and tin cans, coil, electric buzzer, lion's roar, metal waste basket, and water gong (Imaginary Landscape No. 2). Percussionists are Regina Brija, Maya Gunji, John Jutsum, and Patricia Niemi. All are graduates of The Juilliard School. SUMMERGARDEN has been made possible by a grant from the Mobil Corporation A special feature of the 1988 series is the Summer Cafe\ offering light refreshments and beverages. -

Department of Music John Cage's Quartet For

DEPARTMENT OF MUSIC JOHN CAGE’S QUARTET FOR PERCUSSION: ORIGINALITY THROUGH COLLECTIVE INFLUENCE RECITAL RESEARCH PAPER by Michael Feathers Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Music June 17, 2014 Fig. 1. Title page from the original manuscript of John Cage’s Quartet for Percussion. Used with permission by the John Cage Trust. Introduction John Cage was one of the most influential composers of the twentieth century. His status as a musical pioneer began when he listened to and absorbed the styles of other modern composers during the 1920s and 1930s such as Henry Cowell and Arnold Schoenberg. During this period many young composers gravitated toward the styles of either Arnold Schoenberg or Russian composer Igor Stravinsky. Because of Cage’s iconoclastic nature, he was instinctively drawn to the Schoenberg aesthetic and sought an opportunity to meet with Schoenberg. He was given the chance to study formal compositional techniques and he attempted to tackle Schoenberg’s own twelve-tone system. It was around this time that, after a few efforts writing in the atonal style, Cage ultimately admitted that he had no ear for harmony and began composing for percussion, thus beginning his journey toward originality that forever broadened the definition of musical sound. 1 The scope of this research will examine John Cage’s first percussion composition, Quartet for Percussion (1935), on an historical and analytical basis in order to define his early style and influences. Although Cage tirelessly sought the opportunity to study with Schoenberg in the early 1930s, other composers and artists who had a more direct impact on Cage’s signature sound will also be discussed. -

01-33-00 Submittal Procedures

California Polytechnic State University April 15, 2020 [project title] [project #] NOT FOR USE WITHOUT EDITING SECTION 01 33 00 - SUBMITTAL PROCEDURES PART 1 - GENERAL 1.1 RELATED DOCUMENTS A. Construction Drawings, Technical Specifications, Addenda, and general provisions of the Contract, including Contract General Conditions and Supplementary General Conditions and other Division 1 Specification Sections, apply to this Section. 1.2 SECTION INCLUDES A. Administrative requirements B. Construction Progress Schedule Submittal C. Contractor's review of submittals. D. Architect's review of submittals. E. Product data submittals. F. Shop drawing submittals. G. Sample submittals. H. Manufacturer’s Instructions I. Reports of results of tests and inspections. J. Operations and Maintenance Data submittals K. Certificates 1.3 RELATED SECTIONS A. Section 01 31 13 – Project Coordination B. Section 01 31 26 – Electronic Communications Protocol C. Section 01 45 00 - Quality Control: Test and inspection reports. D. Section 01 77 00 - Closeout Procedures: Submittals for occupancy, Acceptance and Final Payment. E. Section 01 78 23 - Operation and Maintenance Data: Requirements for preparation and submission. SUBMITTAL PROCEDURES 01 33 00 - 1 California Polytechnic State University April 15, 2020 [project title] [project #] NOT FOR USE WITHOUT EDITING 1.4 DEFINITIONS A. Shop Drawings, Product Data and Samples: Instruments prepared and submitted by Contractor, for Contractor's benefit, to communicate to Architect the Contractor's understanding of the design intent, for review and comment by Architect on the conformance of the submitted information to the general intent of the design. Shop drawings, product data and samples are not Contract Documents. Drawings, diagrams, schedules and illustrations, with related notes, are specially prepared for the Work of the Contract, to illustrate a portion of the Work. -

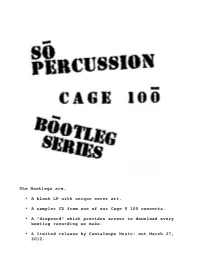

Press Kit and Program Notes for the John Cage Bootlegs Project

The Bootlegs are… • A blank LP with unique cover art. • A sampler CD from one of our Cage @ 100 concerts. • A “dropcard” which provides access to download every bootleg recording we make. • A limited release by Cantaloupe Music: out March 27, 2012. “Music is continuous; only listening is intermittent” -John Cage, after Henry David Thoreau John Cage’s artistic legacy is formidable. His innovations and accomplishments are truly staggering: Cage wrote some the first electric/acoustic hybrid music, the first significant body of percussion music, the first music for turntables, invented the prepared piano, and had a huge impact in the fields of dance, visual art, theater, and critical theory. Somehow Cage’s prolific output seems not to stifle, but rather to spur creativity in others. He certainly deserves surveys, tributes, and portraits during the centenary of his birth. But Sō Percussion wanted to do him honor by allowing his work and spirit to infuse our own. In 2012, we decided to put Cage’s music together with new music created for the occasion. We believe that most of it should not strive towards the “definitive,” but be ever changing and always new. Whether or not that lofty goal is achieved, we’re going to throw up a couple of mics every time we play it and see what happens. 2 Performance Dates and Venues of Bootleg Recordings 2011 Friday, September 9 - 9pm Musikfest Bremen Bremen, Germany Friday, September 16 - 7:30pm Pittsburg State University Pittsburg, KS Monday, October 24 - 7:30pm Friends of Chamber Music Portland, OR Wednesday, October 26 - 8pm Stanford Lively Arts Palo Alto, CA Saturday, October 29 - 8pm; Sunday, October 30 - 2pm The Mondavi Center U.C.