The Man Who Loved Golf to Death

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

•Da Etamettez

:f-liEer all is said and done, more is said than done. igdom al MISSIONARY PREMILLENNIAL BIBLICAL BAPTISTIC ind thee "I Should Like To Know" shall cad fire: thee 1. Is it Scriptural to send out abound." He wrote Timothy to lashing 01, women missionaries? come by Bro. Carpus' and bring Etamettez his old coat he had left there. •da Personally, I don't think much urnace of the practice. However, such the gnash' 3. Does the "new heart" spoken could be done Scripturally. Of of in Ezek. 11:19 have reference .ed moatO Paid Girculalien 7n Rii stales and 7n Many Foreign Gouniries course their work should be con- iosts that to the divine nature implanted in testimony; if they speak not according to this word fined to the limits set by the Holy man at the new birth? , beloved, "To the law and to the Spirit in the New Testament. But I says, it is because there is no light in them."-Isaiah 8:29. Paul mentions by name as his Yes. II Pet. 1:4. In repentance .1 into the helpers on various mission fields, we die to sin and the old life; in Phoebe, Priscilla, Euodias, Synty- faith we receive Christ who is our Is us of 1 VOL. 23, NO. 51 RUSSELL, KENTUCKY, JANUARY 22, 1955 WHOLE NUMBER 868 che and others. In Romans 16 he new life. Col. 3:3-4. John 1:12-13. this world mentions a number of women, I John 5:10-13. Our headship fullest Who evidently were workers on passes from self to Christ. -

Auction - Sale 632: Golf Books by the Shelf 01/04/2018 11:00 AM PST

Auction - Sale 632: Golf Books by the Shelf 01/04/2018 11:00 AM PST Lot Title/Description Lot Title/Description 1 24 Golf Books 3 32 Golf Books Includes:Allen, Peter. Famous Fairways. London: Stanley Paul, Includes:Balata, Billy. Being The Ball. Phoenix, Arizona: B.T.B. 1968.Allison, Willie. The First Golf Review. London: Bonar Books, Entertainment, 2000.Beard, Frank. Shaving Strokes. New York: Grosset 1950.Alliss, Peter. A Golfer’s Travels. London: Boxtree, 1997.Alliss, & Dunlap, 1970.Canfield, Jack. Chicken Soup For The Golfer’s Soul: Peter. Bedside Golf. London: Collins, 1980.Alliss, Peter. More Bedside The 2nd Round. Florida: Health Communications, 2002.Canfield, Jack. Golf. London: Collins, 1984.Alliss, Peter. Yet More Bedside Golf. Chicken Soup For The Soul. Cos Cob, Connecticut: Chicken Soup For London: Collins, 1985.Ballesteros, Severiano. Seve. Connecticut: Golf The Soul Publishing, 2008.Canfield, Jack. Chicken Soup For The Soul Digest, 1982.Cotton, Henry. Thanks For The Game. London: Sidgwick & And Golf Digest Present THE GOLF BOOK. Cos Cob, Connecticut: Jackson, 1980.Crane, Malcolm. The Story Of Ladies’ Golf. London: Chicken Soup For The Soul Publishing, 2009.Canfield, Jack. Chicken Stanley Paul, 1991.Critchley, Bruce. Golf And All Its Glory. London: B B Soup For The Woman Golfer’s Soul. Florida: Health Communications, C Books, 1993.Follmer, Lucille. Your Sports Are Showing. : Pellegrini & 2007.Coyne, John. The Caddie Who Won The Masters. Oakland, Cudahy, 1949.Greene, Susan. Consider It Golf. SIGNED. Michigan: California: Peace Corps Writers Book, 2011.Ferguson, Allan Mcalister. Excel, 2000.Greene, Susan. Count On Golf. SIGNED. Michigan: Excel, Golf In Scotland. -

$75,000 in CASH & PRIZES*

$75,000 in CASH & PRIZES* st th August 31 – Sept. 4 , 2011 Wednesday, Aug.31st - Charity Pro-am 2010 Van Open Champion: Adam Hadwin Fraserview Golf Course – 1pm Shotgun Thursday, Sept.1st - Practice Rounds (Details on practice round rates TBA) Friday, Sept.2nd - Round One McCleery Golf Course – 7:30 am Start Professionals and Championship Amateurs Langara Golf Course – 7:30 am Start Flight A and B Amateurs Saturday, Sept.3rd - Round Two Langara Golf Course – 7:30am Start Professionals and Championship Amateurs The 54-Hole Championship includes: McCleery Golf Course – 7:30 am Start Flight A and B Amateurs Great tee-gift; Buffet lunch each day you compete th Guaranteed 36 holes of golf (18 holes at McCleery Sunday, Sept.4 - Final Round and 18 holes at Langara). Fraserview Golf Course – 7:30am Start Live Leaderboard screens on course Driving range warm-up at McCleery and 36-Hole Cut: Fraserview Professionals: Top 60% and ties make the 36-hole cut Fantastic Prize table for top gross and net scores Amateurs: Top 60% and ties in each Amateur Flight (Gross scores in Championship; Net scores in Flight A 2010 Amateur Champion: Kris Yardley (L) and B) make the cut to play the final round. Eligibility Open to Pros & Amateurs with RCGA Factor 18.0 or less. Full Field: 224 golfers (100 pros; 124 amateurs). Pro Purse: $50,000* 1st Place: $10,000* *Based on Full Field Championship Entry Fees Professionals: VGT Preferred Members: $350 + tax CPGA/Can Tour Members: $400 + tax Non-VGT/CPGA/Can Tour: $500 + tax Amateurs: VGT Preferred Members: $225 + tax Spectator Tickets: VGT Basic or Non-Members: $275 + tax $10/per day or $20 for full week pass. -

Golf World Presents Revised Calendar of Events for 2020 Safety, Health and Well-Being of All Imperative to Moving Forward

Golf World Presents Revised Calendar of Events for 2020 Safety, Health and Well-Being of All Imperative to Moving Forward April 6, 2020 – United by what may still be possible this year for the world of professional golf, and with a goal to serve all who love and play the game, Augusta National Golf Club, European Tour, LPGA, PGA of America, PGA TOUR, The R&A and USGA have issued the following joint statement: “This is a difficult and challenging time for everyone coping with the effects of this pandemic. We remain very mindful of the obstacles ahead, and each organization will continue to follow the guidance of the leading public health authorities, conducting competitions only if it is safe and responsible to do so. “In recent weeks, the global golf community has come together to collectively put forward a calendar of events that will, we hope, serve to entertain and inspire golf fans around the world. We are grateful to our respective partners, sponsors and players, who have allowed us to make decisions – some of them, very tough decisions – in order to move the game and the industry forward. “We want to reiterate that Augusta National Golf Club, European Tour, LPGA, PGA of America, PGA TOUR, The R&A and USGA collectively value the health and well-being of everyone, within the game of golf and beyond, above all else. We encourage everyone to follow all responsible precautions and make effort to remain healthy and safe.” Updates from each organization follow, and more information can be found by clicking on the links included: USGA: The U.S. -

Greatest Generation

Note: This show periodically replaces their ad breaks with new promotional clips. Because of this, both the transcription for the clips and the timestamps after them may be inaccurate at the time of viewing this transcript. 00:00:00 Music Transition Dark Materia’s “The Picard Song,” record-scratching into a Sisko- centric remix by Adam Ragusea. Picard: Here’s to the finest crew in Starfleet! Engage. [Music begins. A fast-paced techno beat.] Picard: Captain Jean-Luc Picard, the USS Enterprise! [Music slows, record scratch, and then music speeds back up.] Sisko: Commander Benjamin Sisko, the Federation starbase... Deep Space 9. [Music ends.] 00:00:14 Music Music Record scratch back into "The Picard Song," which plays quietly in the background. 00:00:15 Ben Harrison Host Welcome to The Greatest Generation... [dramatically] Deep Space Nine! It's a Star Trek podcast from a couple of guys who are a little bit embarrassed to have a Star Trek podcast. And a little bit embarrassed to open their podcast the way I just did. [Stifles laughter.] I'm Ben Harrison. 00:00:29 Adam Host I'm Adam Pranica. There's nothing I can do about it. Pranica [Ben laughs.] When you open a show this way. Except just— 00:00:34 Ben Host You can't help me! 00:00:35 Adam Host —just sit back and watch. [Music fades out.] 00:00:37 Ben Host I hoisted myself on my own petard. That's what happened today. 00:00:41 Adam Host You're a voice acting professional! [Ben chuckles.] I mean, you take those kind of risks. -

PGA TOUR Player/Manager List

2016 PGA TOUR Player/Manager List Generated On: 2/17/2016 - A - ADAMS, Blake - 1 Degree Management, LLC AIKEN, Thomas - Wasserman Media Group - London ALLEM, Fulton - Players Group, Inc ALLENBY, Robert - MVP, Inc. ALLEN, Michael - Medalist Management, Inc. ALLRED, Jason - 4U Management, LLC AL, Geiberger, - Cross Consulting AMES, Stephen - Wasserman Media Group - Canada ANCER, Abraham - The Legacy Agency ANDERSON, Mark - Blue Giraffe Sports ANDRADE, Billy - 4Sports & Entertainment ANGUIANO, Mark - The Legacy Agency AOKI, Isao - High Max APPLEBY, Stuart - Blue Giraffe Sports ARAGON, Alex - Wasserman Media Group - VA ARMOUR III, Tommy - Tommy Armour, III, Inc. ARMOUR, Ryan - IMG ATKINS, Matt - a3 Athletics AUSTIN, Woody - The Legacy Agency AXLEY, Eric - a3 Athletics AZINGER, Paul - TCP Sports Management, LLC A., Jimenez, Miguel - Marketing and Management International - B - BADDELEY, Aaron - Pro-Sport Management BAEK, Todd - Hambric Sports Management BAIRD, Briny - Pinnacle Enterprises, Inc. BAKER-FINCH, Ian - IMG Media BAKER, Chris - 1 Degree Management, LLC BALLO, JR., Mike - Lagardere Sports BARBER, Blayne - IMG BARLOW, Craig - The Legacy Agency BARNES, Ricky - Lagardere Sports BATEMAN, Brian - Lagardere Sports - GA BEAUFILS, Ray - Wasserman Media Group - VA BECKMAN, Cameron - Wasserman Media Group - VA BECK, Chip - Tour Talent BEEM, Rich - Marketing and Management International BEGAY III, Notah - Freeland Sports, LLC BELJAN, Charlie - Meister Sports Management BENEDETTI, Camilo - The Legacy Agency BERGER, Daniel - Excel Sports Management BERTONI, Travis - Medalist Management, Inc. BILLY, Casper, - Pinnacle Enterprises, Inc. BLAUM, Ryan - 1 Degree Management, LLC BLIXT, Jonas - Lagardere Sports - FL BOHN, Jason - IMG BOLLI, Justin - Blue Giraffe Sports BOWDITCH, Steven - Players Group, Inc BOWDITCH, Steven - IMG BRADLEY, Keegan - Lagardere Sports - FL BRADLEY, Michael - Lagardere Sports BREHM, Ryan - Wasserman Media Group - Wisconsin BRIGMAN, D.J. -

2010 Aicp Show Shortlist

2010 AICP SHOW SHORTLIST Category: Visual Style Title Production Company Agency ABSOLUT Vodka Anthem MJZ TBWAChiatDay ABSOLUT Vodka I'm Here Trailer MJZ TBWAChiatDay Activision Captivity MJZ Toy New York Barclays Fake MJZ Venables, Bell & Partners ITV Brighter Side MJZ BBH Jameson Irish Whiskey Lost Barrel Biscuit Filmworks TBWA\Chiat\Day, New York Levis America Anonymous Content Wieden + Kennedy Nike Human Chain Smuggler Wieden+Kennedy, Portland Sony Jessica Sanders Innocuous Media 180LA U.S. Cellular Shadow Puppets Anonymous Content Publcis & Hal Riney X BOX Halo 3:ODST The Life MJZ T.A.G. San Francisco. Category: Performance Dialogue or Monologue Title Production Company Agency Bud Light Clothing Drive Tool DDB FedEx Presentation Guy O Positive BBDO New York Old Spice The Man Your Man Can Smell Like MJZ Wieden + Kennedy Skittles Plant Smuggler TBWA\Chiat\Day, New York Skittles Transplant Smuggler TBWA\Chiat\Day, New York Snickers Game MJZ BBDO New York Snickers Road Trip MJZ BBDO New York Starburst Kilt MJZ TBWA Chiat Day Tribeca Film Festival Flasher Station Film Ogilvy & Mather Virgin Atlantic Becoming O Positive Y&R New York Category: Humor Title Production Company Agency Brand Jordan Get Your Basketball On MJZ Wieden + Kennedy NY Bud Light Clothing Drive Tool DDB Comcast Infomercial Biscuit Filmworks Goodby Silverstein & Partners ESPN - Monday Night Football Brady's Back Epoch Films Wieden+Kennedy New York Fruit by the Foot Replacements MJZ Saatchi & Saatchi NY Hardee's A vs. B Station Film Mendelsohn Zien MTV Slaughter Shack Backyard -

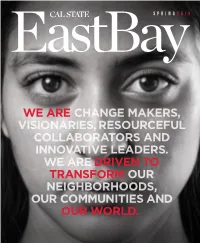

Change Makers, Visionaries, Resourceful Collaborators and Innovative Leaders

SPRING2019 WE ARE CHANGE MAKERS, VISIONARIES, RESOURCEFUL COLLABORATORS AND INNOVATIVE LEADERS. WE ARE DRIVEN TO TRANSFORM OUR NEIGHBORHOODS, OUR COMMUNITIES AND OUR WORLD. magazine is published by the Office Editor Inquiries of University Communications and Natalie Feulner Send your letter to the editor, submit Marketing, a department of the a class note or update your address/ Division of University Advancement. Graphic Designers subscription preferences, including the Kent Kavasch option to receive Cal State East Bay President Gus Yoo magazine electronically, Leroy M. Morishita by contacting: Contributing Writers University Advancement Elias Barboza [email protected] Bill Johnson, Natalie Feulner Vice President Dan Fost Or mail to: Robert Phelps Cal State East Bay Holly Stanco, SA 4800 Associate Vice President, Photography 25800 Carlos Bee Blvd. Development Garvin Tso ’07 Hayward, CA 94542 Richard Watters ’13, Contributing Copyeditor * Please note: Letters will be printed at Executive Director, Alumni Melanie Blake the discretion of Cal State East Bay Engagement & Annual Giving and may be edited for publication. COVER: Melani is a sophomore at Cal State East Bay and breaking The CORE is Cal State East Bay’s newest building, barriers as the first in her family to attend college and one of only a scheduled to open fall 2021. Learn more about the work few women in the university’s construction management program. that will take place within CORE on page 12. An immigrant from El Salvador, she embodies Cal State East Bay’s COURTESY OF CARRIER JOHNSON + CULTURE commitment to social mobility and exemplifies the hard work, determination and drive our students bring to the work they do every day. -

Thegrass ROOTS

The GRASS ROOTS AN OFFICIAL PUBLICATION OF THE WISCONSIN GOLF COURSE SUPERINTENDENTS ASSOCIATION VOL. XLVI ISSUE 1 MARCH/APRIL 2017 From Reservoir to Rotor... Rain Bird has you covered. To learn more, contact your local sales rep today! Lush fairways and manicured greens can also be highly water-ecient. Every Rain Bird product is a testament to that Mike Whitaker Northern Wisconsin truth. From water-saving nozzles to highly ecient pumps to (309) 287-1978 leading-edge Control Technology, Rain Bird products make the [email protected] most of every drop, delivering superior results with less water. Dustin Peterson Keeping the world and your golf course beautiful. Southern Wisconsin That’s The Intelligent Use of Water.™ (309) 314-1937 [email protected] TABLE OF CONTENTS THE PRESIDENTS MESSAGE Spring Fever . 4 THE GRASS ROOTS is the bi-monthly publication of the Wisconsin Golf WISCONSIN PATHOLOGY REPORT Course Superintendents Association printed by e Continuing Debate Surrounding Snow Spectra Print. No part of the THE GRASS ROOTS Mold Fungicide Reapplications . 6 may be used without the expressed written permis- BUSINESS OF GOLF sion of the editor. WSGA, WPGA Spring Symposium Covers David A Brandenburg, CGCS, EDITOR Wide Range of Topics . 10 Rolling Meadows Golf Course MEMBER SPOTLIGHT PO 314 eresa, WI 53091 Patrick Reuteman and Jaime Staufenbeil . 14 [email protected] WISCONSIN ENTOMOLOGY REPORT Considerations When Using Post-Patent (Generic)Products . 18 WGCSA Managing More an Turf . 20 TURFGRASS DIAGNOSTIC LAB Plant Disease Diagnostics: Art or Science? . 24 NORTHERN GREAT LAKES ASSOCIATION Spring Educational Conference Review . 26 2017 WGCSA OFFICERS AND DIRECTORS NOTES FROM THE NOER Front Row: Jim Van Herwynen, Jon Canavan, Josh Ocially, Spring Is Here . -

Tour Edge Re-Signs 3-Time World Long Drive Champ Phillis Meti to Play EXS Driver for 2019

Tour Edge Re-Signs 3-Time World Long Drive Champ Phillis Meti to Play EXS Driver for 2019 Tour Edge announced today that Phillis Meti has officially re-signed a deal to play Tour Edge Exotics drivers in World Long Drive competition and remain as a global staffer for Tour Edge. The partnership will feature the Tour Edge logo on both sides of her hat and on her staff bag. “It’s great to be a part of the Global Tour Edge family for 2019 and I’m so excited to be playing the Exotics EXS driver in competition,” said Meti. “The driver has tested extremely well and I can’t wait to get going with EXS in the new season! 2019 is going to be a special year defending my World title! Look out for some tips and insights over social media I’ll be doing on driving the ball with the EXS Driver in the near future.” Meti won the 2018 World Long Drive Championship with an Exotics driver, her 2nd World Long Drive Championship in the last three years playing Exotics. The new deal will feature Meti sharing driving tips via Tour Edge’s social media channels onhitting the ball long and straight, as well as being featured at the PGA Merchandise Show in 2020 as a Tour Edge staffer. “We are so proud to have Phillis back on board with Tour Edge representing Exotics drivers on the World Long Drive circuit,” said designer of the Exotics EXS driver and President of Tour Edge, David Glod. Meti won the biggest long drive event in the world with a 313 yard drive in the final round of the live for television Golf Channel event to become a 3- time World Champion. -

THE PLAYERS First-Timers Press Conference Wednesday, March 19, 2021

THE PLAYERS First-Timers Press Conference Wednesday, March 19, 2021 PLAYER BIOS Cameron Davis Birthplace: Sydney, Australia Residence: Seattle, Washington College: N/A How he qualified for THE PLAYERS: Top 125 in FedExCup standings from start of 2019-20 season through 2021 WGC-Workday Championship Fast Facts: • Surprisingly won the 2017 Australian Open at The Australian Golf Club after beginning the final round six strokes back of the lead. Held off the likes of Jason Day and Jordan Spieth to win his first professional tournament in his backyard. • Moved to Seattle after turning professional where he met girlfriend Jonika Melcher, whom he proposed to on April 21, 2019. They were married on September 5, 2020 in Seattle. • Best PGA TOUR finish: 3rd at 2021 The American Express Doug Ghim Birthplace: Des Plaines, Illinois Residence: Las Vegas, Nevada College: University of Texas How he qualified for THE PLAYERS: Non-exempt below the No. 10 position in FedExCup standings as necessary to fill the field to 154 players Fast Facts: • Was the 2018 Ben Hogan Award recipient (nation's best collegiate golfer) as a senior at the University of Texas. • Because he was a recipient of an AJGA ACE Grant, which gave him the financial means necessary to play a national golf schedule, Doug gives back to the AJGA Foundation. • Played the 2018 Masters (T50) as the runner-up of the 2017 U.S. Amateur. • Doug grew up playing municipal courses; he was not a member of a country club. He recalled playing with used clubs purchased off eBay. He said he didn’t open a box of new golf balls until he was about 16; even then they were free. -

Golf Event Contests & Fundraising Activities

A GUIDE FOR GOLF EVENT ORGANIZERS Golf Event Contests & Fundraising Activities NEW PLANNER Tournament TOOLS planning LOOK INSIDE tips, tricks & tools HOW TO PLAN AUCTIONS & RAFFLES up the antE with a $1 million shot If your golf event is a fundraising event, then your contests, auctions and raffles are a great way to raise more money. If your event is not a fundraising golf event, these activities still add to the overall player experience at your event. One important goal of a golf event is to provide the players with a memorable experience in an addition to the actual golf. This is why these activities are so popular. However, it is important to run the activities properly so that players feel everyone had a fair opportunity to win. 1 Introduction GolfDigestTournamentShop.com Contents This book 3 Hole in One Contests 4 Putting Contests is a guide 6 Chipping Contests to organizing 6 $1 Million Shot and running 7 $50,000 and $100,000 Shootouts the most popular 7 Long Drive Contests 8 Closest to the Pin events for your 8 Straight Drive golf event. 9 Mulligans 10 Auctions and Raffles 12 Silent Auction Bid Sheet 13 Auction Item List GolfDigestTournamentShop.com Contents 2 Hole in One Contests Hole in one contests are great for fundraising. Sell a sponsorship for each Par 3 hole to raise money for your event. Hole in one contests provide four sponsorship opportunities for your event. You can sell a sponsorship for each hole. This will cover the cost of your hole in one prize package and generate a profit for your event if you are holding a fundraising golf event.