Air Resources Board

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Capitalizing on Men's Vanity

CAPITALIZING ON MEN’S VANITY: A qualitative study of men’s behavior when evaluating, buying and using men’s grooming products. MASTER THESIS MSc Brand and Communication Management Copenhagen Business School 2014 Author: Pernille Burkhalter Supervisor: Jesper Clement Hand-in date: 20.08.2014 Number of pages: 83 (excluding appendices) Number of characters: 174 461 (excluding appendices) Abstract Grooming products especially designed and developed for men is a fast growing industry, however, little attention has been devoted to understanding the male consumer in regards to this product category. The purpose of this thesis was to investigate Norwegian men’s consumer behavior when buying and using grooming products in order for the cosmetic industry to better capitalize this market. A review of the Norwegian grooming market and how it is currently being capitalized served as the starting point, and a conceptual framework was developed based on consumer behavior theory and contemporary studies in the field, creating a base for primary data collection. Methods of data collection included in-depth interviews with 7 Norwegian men, in- store participant observation and follow-up interviews, in addition to interviews with in-store experts. The conceptual framework and the method for data collection chosen provided a good level of explanatory power and interesting themes emerged, namely: Involvement & Knowledge, Notions of Masculinity, Hairstyle and Identity, False loyalty, Avoidance of Feminine Behavior, Significant Females, and Importance of Quality. Making it possible to better understand men’s consumer behavior when evaluating, purchasing and using men’s grooming products and on the basis of this knowledge recommend how the industry can better capitalize the Norwegian grooming market for men. -

Gong Farmer, Shit Stirrer and the Maiden of Grief

GONG FARMER, SHIT STIRRER AND THE MAIDEN OF GRIEF LISA ROBERTSON DEC 7: Madison Bycroft [MB] to Lisa Robertson [LR] IN CONVERSATION WITH I just bought your book R’s Boat. It should arrive today or tomorrow. MADISON BYCROFT I’d be interested in hearing a little bit more about your territory and recent experiments, in which ways the indexical method developed. One film for the show is finished. Jolly Roger & Friends. It is 60 min- utes long - so it’s movement and looping becomes a clock. TIME PASSES. It is kind of ‘about’ not being about Mary Read and Anne Bonny, and thus is implicitly about them, somehow, anyway. Anne and Mary were This conversation takes place via e-mail and stretches two pirates who lived in the 18th century, who had to pass and were through the whole period during which the artists read as men for most of their lives. There is a lot of historical ma- develops their initial idea into final results. 1646 invites terial that focussed on this, their sexuality, were they in a secret the correspondent at the other end of this contact to relationship? who knew the “truth”, blah blah blah… I wanted to make figure his/her way through this actual process. a work that wasn’t about revealing them yet stayed with them, and at In trying to picture what result the artists’ work is the same time questioning the idea of ‘them’, their identities, as something that can be revealed at all. getting to, such exchange can become a reflection on the amount of otherwise untraceable choices of the I grapple a lot with ideas of form and content and surface and inte- moment which make up to the artists’ practice. -

The Science of Risk Assessment As It Applies to Cosmetic Products

The Science of Risk Assessment as it Applies to Cosmetic Products Timothy Stakhiv Ph.D., D.A.B.T. L’Oreal USA May 8, 2018 MASOT Webinar “Safety Assessment of Consumer Products” OUTLINE • Definition of Risk Assessment and Margin of Safety • General process of conducting a safety evaluation for cosmetics • Hazard identification • Exposure Assessment • Risk Characterization and Finished Product Assessment • Examples Risk Assessment • The systematic scientific characterization of potential adverse health effects resulting from human exposure to hazardous agents • Hazard identification: Determination of whether exposure to a chemical or ingredient is likely to cause a specific adverse health effect in humans (e.g. eye irritant; liver toxin) • Dose-response assessment: Association between dose and the incidence of a defined biological effect in an exposed population (e.g. No-Observable-Adverse- Effect-Level or NOAEL) • Exposure assessment: determine source, type, magnitude, duration of contact • Risk characterization: integrates Hazard identification, Dose-Response Assessment, and Exposure Assessment to determine… • the probability of an adverse effect to a human population by a toxic substance • permissible exposure levels from which standards of exposure are set • Margin of Safety Margin of Safety (MoS) • Ratio of the NOAEL to the estimated systemic exposure dose (SED) NO(A)EL MoS SED • Safety factors are considered – Species differences – Human variability – Differences between adults and children/babies Safety Evaluation of Cosmetics • Safety -

You Can't Fault the Ancient Egyptians for Smelling Less Than Fresh

001-011_Gross_FM_REL.indd 1 4/19/12 5:08 PM 6 66001-011_Gross_FM_REL.indd6 2 4/18/126 10:59 AM That ’s GROSS! BY CRISPIN BOYER WASHINGTON, D.C. 666001-011_Gross_FM_REL.indd 3 4/18/12 10:59 AM GROSS Contents Meet Your Gross Host! . .6 Magical Mucus. 38 How to Get the Most From That’s Gross! . .8 Urine Nation: Wee Will Rock You . 40 Welcome to Your Happy Place! . 10 Fecal Matters: The Scoop on Poop . 42 i You Are So Gross! . 44 CHAPTER 1: Horribleble HHistoryistoo . 12 Freeze That Sneeze! . 46 History Stinks . 14 Gross Grudge Match: Gas Attack . 48 A Toilet Time Line: Potty Spotting . 16 What’s Up, Chuck? The Putrid Truth About Puke. 50 Bad Medicine . 18 The 7 Faces of Feces . 52 Meet the Mummies. 20 Disgusting Statistics/Gag Gauge . 54 How to Make a Mummy . 22 Dirty Work: History’s Five Nastiest Careers . 24 Who’s for Dinner? . 26 CHAPTER 3: Nasty Nature . 56 Gross Grudge Match: Space Invader . 58 Roman Feast vs. Medieval Banquet . 28 Awful Animal Awards . 60 History’s Worst Firsts . 30 Why Does My Dog Eat Doo?!. 62 Horrible History Lesson/Gag Gauge. 32 Why Does My Cat Hack Up That?! . 64 1 Aww, Cute! / Oh, Yuck! . 66 CHAPTER 2: Your Abominable Body . 34 Quirks of Nature . 68 Germs! Germs! Germs! . 36 Sea Monsters! . 70 64 6001-011_Gross_FM_REL.indd 4 4/18/12 10:59 AM Gross Grudge Match: The Ack-ademy Awards! . 120 Naked Mole Rat vs. Hagfi sh . 72 Eww ’Toons! . 122 Disgustingly Adorable . 74 Plop Culture . -

ISIC) Is the International Reference Classification of Productive Activities

Economic & Social Affairs @ek\ieXk`feXcJkXe[Xi[@e[ljki`Xc:cXjj`]`ZXk`fef]8cc<Zfefd`Z8Zk`m`k`\j@J@: #I\m%+ @ek\ieXk`feXcJkXe[Xi[@e[ljki`Xc :cXjj`]`ZXk`fef]8cc<Zfefd`Z 8Zk`m`k`\j@J@: #I\m%+ Series M No. 4, Rev.4 Statistical Papers asdf United Nations Published by the United Nations ISBN 978-92-1-161518-0 Sales No. E.08.XVII.25 07-66517—August 2008—2,330 ST/ESA/STAT/SER.M/4/Rev.4 Department of Economic and Social Affairs Statistics Division Statistical papers Series M No. 4/Rev.4 International Standard Industrial Classification of All Economic Activities Revision 4 asdf United Nations New York, 2008 Department of Economic and Social Affairs The Department of Economic and Social Affairs of the United Nations Secretariat is a vital interface between global policies in the economic, social and environmental spheres and national action. The Department works in three main interlinked areas: (i) it compiles, generates and analyses a wide range of economic, social and environ- mental data and information on which States Members of the United Nations draw to review common problems and to take stock of policy options; (ii) it facilitates the negotiations of Member States in many intergovernmental bodies on joint courses of action to address ongoing or emerging global challenges; and (iii) it advises interested Governments on the ways and means of translating policy frameworks developed in United Nations conferences and summits into programmes at the country level and, through technical assistance, helps build national capacities. Note The designations used and the presentation of material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. -

Hairdressers

Projekt Nové kompetence žák ů v odborném vzd ělávání Č. projektu: CZ.1.07/1.1.36/02.0008 Coursebook for the study branch: Hairdressers Made by: Mgr. Dagmar Kotlíková English for hairdres sers Teacher´s book Dagmar Kotlíková CONTENT 2 Content MY JOB ....................................................................................................................... 4 Wordlist .....................................................................................................................................5 TOOLS 1 ....................................................................................................................... 6 Vocabulary in use ........................................................................................................ 7 Wordlist ...................................................................................................................................12 TOOLS 2 ..............................................................................................................................13 Vocabulary in use ..................................................................................................................14 Wordlist ...................................................................................................................................16 HAIRDRESSING SALON .................................................................................................... 17 MEN´S CARE .......................................................................................................................19 -

Nouvelle Institute

NOUVELLE INSTITUTE 3271 NW 7th Street Suite 106 500 West 49th St, 2nd Floor Miami, 33125 Hialeah, Florida, 33012 Tel (305) 643 3360 Tel. (305) 557 3017 Lic. # 1393 Lic. # 2074 CATALOG Licensed by: The Commission for Independent Education, Florida Department of Education 325 West Gaines Street, Suite 1414 Tallahassee, Florida 32399-0400 – Toll Free Telephone Number (888)224-6684 Accredited by National Accrediting Commission of Career Arts & Sciences, (NACCAS) 3015 Colvin Street Alexandria, Virginia 22314 Phone (703) 600-7600 Owned By: Montano Pabon & Associates, Inc. Incorporated under the Business Corporations Laws of the State of Florida Revised August 2021 0 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page’s number Mission Statement 3 Accredited by 3 Licensed by 3 Ownership / Governing Body 3 Location 3 Facilities and Equipment 3 Faculty and Administrative Staff -Miami 4 Faculty and Administrative Staff -Hialeah 4 Corporate Officers 4 Admission Requirement for all Programs 5 Transfer Policy 5 Re- Entry Policy 5 Ability to Benefit (ATB) 6 Wonderlic Test 6 Faculty Credentials 6 Grading System 6 Student Records 6 Satisfactory Academic Progress Policy 6-9 Policy for Attendance, tardiness and make up 8 Leave of Absent Policy (LOA) 8 Definition of Administrative and Official Withdrawals 8 Transfer Policy 9 Withdrawal Policy and Refund Policy 9 Refunds: Return to Title IV 11 Return of Unearned Funds 11 Payment Methods, Payment Plan and Collection 11 Collection of funds owed to the School 11 Additional nonrefundable fee 11 Charge for extra Instruction 11 Non – Discrimination -

List of Hairstyles

List of hairstyles This is a non-exhaustive list of hairstyles, excluding facial hairstyles. Name Image Description A style of natural African hair that has been grown out without any straightening or ironing, and combed regularly with specialafro picks. In recent Afro history, the hairstyle was popular through the late 1960s and 1970s in the United States of America. Though today many people prefer to wear weave. A haircut where the hair is longer on one side. In the 1980s and 1990s, Asymmetric asymmetric was a popular staple of Black hip hop fashion, among women and cut men. Backcombing or teasing with hairspray to style hair on top of the head so that Beehive the size and shape is suggestive of a beehive, hence the name. Bangs (or fringe) straight across the high forehead, or cut at a slight U- Bangs shape.[1] Any hairstyle with large volume, though this is generally a description given to hair with a straight texture that is blown out or "teased" into a large size. The Big hair increased volume is often maintained with the use of hairspray or other styling products that offer hold. A long hairstyle for women that is used with rich products and blown dry from Blowout the roots to the ends. Popularized by individuals such asCatherine, Duchess of Cambridge. A classic short hairstyle where it is cut above the shoulders in a blunt cut with Bob cut typically no layers. This style is most common among women. Bouffant A style characterized by smooth hair that is heightened and given extra fullness over teasing in the fringe area. -

Product Nomination Form

H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H Beauty H H H H H H &Wellness H PRODUCT H H H H H Awards H NOMINATION H H H H H H H H FORM H H H H H Please fill out all details below: H H H H H H H H H H Company name: Brand name: Contact Person: Designation: Phone: Email address: Please select the Category(s) you are nominating the product(s) for: LADIES’ SECTION 1. Best Hair Product: q Facial sunscreen q Mineral makeup q Shiny/smoothing shampoo/ q Facial mist q Makeup remover volumising conditioner q Acne spot treatment q Cleansing oil/balm q Coloured shampoo/ q Pore-refining/Oil-control conditioner treatment 4. Best Eye Makeup: q Treatment shampoo/ q Brightening / whitening q Eyeshadow primer/base conditioner (dull/dry/ treatment q Eyeshadow damaged/thinning hair) q Anti-aging treatment q Mascara q leave-in/rinse-off treatment q Pigmentation treatment q Liquid eyeliner (dull/dry/damaged/thinning q Eye serum/cream q Gel eyeliner hair) q Eye mask/treatment q Pencil eyeliner q Hairstyling product (anti- q Under eye concealer frizz/voluminising) 3. Best Face Makeup: q Brow powder / pencil / gel q Multi-purpose hair oil q Primer /base q Eye makeup remover q Hair dye q BB cream q Hair spray q CC cream 5. Best Lip Saver: q Dry shampoo q Liquid foundation q Lip balm q Foundation (Gel/Powder/ q Lip liner 2. Best Face Saver: Cream) q Liquid lipstick q Facial cleanser (foam/gel/ q Concealer q Lipstick mousse) q Highlighter (powder /liquid q Lip gloss q Facial essence/Serum/Oil/ /gel/ cream) q Lip tint/stain Toner q Blusher (powder /liquid q Lip plumper q Facial moisturizer (Day/ /gel/ cream) q Lip treatment Night/Everyday) q Loose/Setting/Compact q Facial scrub powder q Face mask q Makeup setting spray H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H Beauty H H H H H H H &Wellness H H H H www.aestheticsandbeauty.com H H Awards H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H 6. -

October 2017 Entrepreneur India Monthly Magazine

RNI NO. 61509/95 www.entrepreneurindia.co ABOUT US NIIR PROJECT CONSULTANCY SERVICES (NPCS) an ISO 9001: 2008 CERTIFIED COMPANY is one of the leading players in the industry endowed with the expertise, sound technical knowledge and intellectual asset. NPCS is a repository of reliable professional information for the entrepreneurial fraternity of India and has well experienced professionals in market research comprising of consultants, experts, field executives, researchers and analysts from different industries and sectors. We strive to provide a global platform for the entire entrepreneurial ecosystem by providing right project for investment, market survey studies and research through our advanced industrial, business and commercial databases. NPCS offering integrated technical consultancy services. Its various services are: Detailed Project Report, Business Plan for Manufacturing Plant, Industry Trends, Market Research, Manufacturing Process, Machinery, Raw Materials, Cost and Revenue, Pre-feasibility study, New Project Identification, Project Feasibility and Market Study, Identification of Profitable Industrial Project Opportunities, Investment Vol. 23 No. 10 Opportunities, Preparation of Project Profiles / Pre-Investment and Pre-Feasibility Studies, Market Surveys OCTOBER 2017 / Studies, Preparation of Techno-Economic Feasibility Reports, Identification and Section of Plant /Process / Equipment, General Guidance, Technical and Commercial Counseling for setting up new industrial EDITOR projects. AJAY KR. GUPTA NPCS also publishes varies books, directories, databases, detailed project reports, market survey D.M.S, M.B.A. reports on various industries and profit making business. Besides being used by manufacturers, industrialists and entrepreneurs, our publications are also used by professionals including project engineers, information Entrepreneurship Management services bureau, consultants and consultancy firms as one of the input in their research. -

We've Put Our Thinking Caps on to Help Your School Have Fun and Twin Some

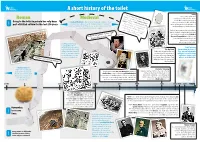

SCHOOL We’ve put our thinking caps on to help your school have fun and twin some toilets! Check out the extra Book a date for a fundraiser or resources online available HOW TO GET STARTED choose us as your charity of to download Go for a fundraising target the year. A Blue for the Loo Day to twin your school toilets might go down well? with the toilets of families in poor comunities , we’ve included: IN THIS PACK An ideas sheet with loads of fun suggestions for fundraising A sample certificate so your school can see what Toilet Twinning is all about A short history of the toilet The word loo originates from a Today French expression “Gardez l’eau!” So it’s only in the past Roman Medieval which means “Watch out for the century and a half that the water water!” People used to empty their closet (WC) or toilet has graced Going to the toilet in private has only been In medieval England in the country, the general rule was that ordinary homes in the UK. And that you would go “a bow’s length” from your home to go to the chamber pots out of bedroom we’ve understood the importance of part of British culture for the last 150 years. windows into the streets so you toilet in a bush or field. That means, as far as you could shoot hand-washing to prevent disease. info leaflet about Toilet Twinning (ask us for more to give them to your students) an arrow away, that was your spot. -

Short History Update

A short history of the toilet The word loo originates from a Today French expression “Gardez l’eau!” So it’s only in the past Roman Medieval which means “Watch out for the century and a half that the water water!” People used to empty their closet (WC) or toilet has graced Going to the toilet in private has only been In medieval England in the country, the general rule was that ordinary homes in the UK. And that you would go “a bow’s length” from your home to go to the chamber pots out of bedroom we’ve understood the importance of part of British culture for the last 150 years. windows into the streets so you toilet in a bush or field. That means, as far as you could shoot hand-washing to prevent disease. an arrow away, that was your spot. had to keep an eye out when you were walking below. Sadly in many parts of the world they still don't have a toilet, which is vital for health and well-being. A third of Inform the palace of the royal the world’s population is still at risk bowels being evacuated! from disease because they don’t have a safe or sanitary place to go to the toilet. In cities people used cesspits which were emptied by gong farmers. Toilet Twinning A gong farmer was a very The Big Stink By spreading the loove of smelly man who owned a In the 1850s parliament had loos, you can help people horse, a cart and a shovel.