Ed Benguiat Obituary

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

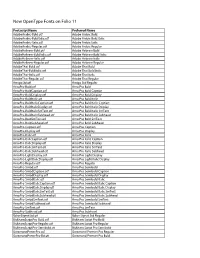

New Opentype Fonts on Folio 11

New OpenType Fonts on Folio 11 Postscript Name Preferred Name AdobeArabic-Bold.otf Adobe Arabic Bold AdobeArabic-BoldItalic.otf Adobe Arabic Bold Italic AdobeArabic-Italic.otf Adobe Arabic Italic AdobeArabic-Regular.otf Adobe Arabic Regular AdobeHebrew-Bold.otf Adobe Hebrew Bold AdobeHebrew-BoldItalic.otf Adobe Hebrew Bold Italic AdobeHebrew-Italic.otf Adobe Hebrew Italic AdobeHebrew-Regular.otf Adobe Hebrew Regular AdobeThai-Bold.otf Adobe Thai Bold AdobeThai-BoldItalic.otf Adobe Thai Bold Italic AdobeThai-Italic.otf Adobe Thai Italic AdobeThai-Regular.otf Adobe Thai Regular AmigoStd.otf Amigo Std Regular ArnoPro-Bold.otf Arno Pro Bold ArnoPro-BoldCaption.otf Arno Pro Bold Caption ArnoPro-BoldDisplay.otf Arno Pro Bold Display ArnoPro-BoldItalic.otf Arno Pro Bold Italic ArnoPro-BoldItalicCaption.otf Arno Pro Bold Italic Caption ArnoPro-BoldItalicDisplay.otf Arno Pro Bold Italic Display ArnoPro-BoldItalicSmText.otf Arno Pro Bold Italic SmText ArnoPro-BoldItalicSubhead.otf Arno Pro Bold Italic Subhead ArnoPro-BoldSmText.otf Arno Pro Bold SmText ArnoPro-BoldSubhead.otf Arno Pro Bold Subhead ArnoPro-Caption.otf Arno Pro Caption ArnoPro-Display.otf Arno Pro Display ArnoPro-Italic.otf Arno Pro Italic ArnoPro-ItalicCaption.otf Arno Pro Italic Caption ArnoPro-ItalicDisplay.otf Arno Pro Italic Display ArnoPro-ItalicSmText.otf Arno Pro Italic SmText ArnoPro-ItalicSubhead.otf Arno Pro Italic Subhead ArnoPro-LightDisplay.otf Arno Pro Light Display ArnoPro-LightItalicDisplay.otf Arno Pro Light Italic Display ArnoPro-Regular.otf Arno Pro Regular ArnoPro-Smbd.otf -

Bibliographica (Issue 3)

Bibliographica (Issue 3) Item Type Newsletter (Paginated) Authors Henry, John G.; Schanilec, Gaylord; Hardesty, Skye Citation Bibliographica (Issue 3) 2005-07, Download date 26/09/2021 12:16:22 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/106505 Issue Number 3 Summer 2005 biBIblBiLIoOGgRrAPapHhICAic a Cedar Creek Press collection of text sizes in Caslon, Garamond, Euse- bius, and Goudy Oldstyle. By John G. Henry Henry’s journey has taken him through high school, Cedar Creek Press has produced a variety of printed a B.A. from the University of Iowa with majors in materials since its inception in 1967. What started English & Journalism, an M.S. degree in Printing entirely as a hobby venture by a high school student Technology from the Rochester Institute of Tech- and a single press has expanded to fill a 25’ x 50’ nology, and many other practical learning experiences. workshop. The reason for being of Cedar Creek Cedar Creek Press has published many books of Press has always been the printer’s enjoyment of Poetry by primarily Midwestern poets. Mostly first the letterpress process. books for the authors, the editions have been small, Proprietor John G. Henry spent many hours poring but have given a published voice to many fine poets. over the catalogs of the Kelsey Company, making The emphasis of the publishing has been to produce his wish-list and saving his allowance for purchase nicely-designed and produced books at a reasonable of a basic set of printing equipment. One day Henry price. saw an advertisement in the local classifieds for an Recent ventures have been in the world of miniature entire print shop for $50. -

The Impact of the Historical Development of Typography on Modern Classification of Typefaces

M. Tomiša et al. Utjecaj povijesnog razvoja tipografije na suvremenu klasifikaciju pisama ISSN 1330-3651 (Print), ISSN 1848-6339 (Online) UDC/UDK 655.26:003.2 THE IMPACT OF THE HISTORICAL DEVELOPMENT OF TYPOGRAPHY ON MODERN CLASSIFICATION OF TYPEFACES Mario Tomiša, Damir Vusić, Marin Milković Original scientific paper One of the definitions of typography is that it is the art of arranging typefaces for a specific project and their arrangement in order to achieve a more effective communication. In order to choose the appropriate typeface, the user should be well-acquainted with visual or geometric features of typography, typographic rules and the historical development of typography. Additionally, every user is further assisted by a good quality and simple typeface classification. There are many different classifications of typefaces based on historical or visual criteria, as well as their combination. During the last thirty years, computers and digital technology have enabled brand new creative freedoms. As a result, there are thousands of fonts and dozens of applications for digitally creating typefaces. This paper suggests an innovative, simpler classification, which should correspond to the contemporary development of typography, the production of a vast number of new typefaces and the needs of today's users. Keywords: character, font, graphic design, historical development of typography, typeface, typeface classification, typography Utjecaj povijesnog razvoja tipografije na suvremenu klasifikaciju pisama Izvorni znanstveni članak Jedna je od definicija tipografije da je ona umjetnost odabira odgovarajućeg pisma za određeni projekt i njegova organizacija s ciljem ostvarenja što učinkovitije komunikacije. Da bi korisnik mogao odabrati pravo pismo za svoje potrebe treba prije svega dobro poznavati optičke ili geometrijske značajke tipografije, tipografska pravila i povijesni razvoj tipografije. -

P Font-Change Q UV 3

p font•change q UV Version 2015.2 Macros to Change Text & Math fonts in TEX 45 Beautiful Variants 3 Amit Raj Dhawan [email protected] September 2, 2015 This work had been released under Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License on July 19, 2010. You are free to Share (to copy, distribute and transmit the work) and to Remix (to adapt the work) provided you follow the Attribution and Share Alike guidelines of the licence. For the full licence text, please visit: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/legalcode. 4 When I reach the destination, more than I realize that I have realized the goal, I am occupied with the reminiscences of the journey. It strikes to me again and again, ‘‘Isn’t the journey to the goal the real attainment of the goal?’’ In this way even if I miss goal, I still have attained goal. Contents Introduction .................................................................................. 1 Usage .................................................................................. 1 Example ............................................................................... 3 AMS Symbols .......................................................................... 3 Available Weights ...................................................................... 5 Warning ............................................................................... 5 Charter ....................................................................................... 6 Utopia ....................................................................................... -

Typestyle Chart.Pub

TYPESTYLE CHART This is an abbreviated list of the typestyles available from 2/90. ADA fonts are designated with either one or two asterisks. Those with two asterisks comply with ANSI A.117.1 standards for enhanced readability of tactile signage elements. Use typestyle abbreviations in parentheses when placing an order. For additional fonts not on this list, contact Customer Service at 800.777.4310. Albertus (ALC) Commercial Script Connected (CSC) Americana Bold (ABC) *Compacta Bold®2 (CBL) Anglaise Fine Point (AFP) Engineering Standard (ESC) *Antique Olive Nord (AON) *ITC Eras Medium®2 (EMC) *Avant Extra Bold (AXB) *Eurostile Bold (EBC) **Avant Garde (AGM) *Eurostile Bold Extended (EBE) *BemboTM1 (BEC) **Folio Light (FLC) Berling Italic (BIC) *Franklin Gothic (FGC) Bodoni Bold (BBC) *Franklin Gothic Extra Condensed (FGE) Breeze Script Connecting (BSC) ITC Friz Quadrata®2 (FQC) Caslon Adbold (CAC) **Frutiger 55 (F55) Caslon Bold Condensed (CBO) Full Block (FBC) Century Bold (CBC) *Futura Medium (FMC) Charter Oak (COC) ITC Garamond Bold®2 (GBC) City Medium (CME) Garth GraphicTM3 (GGC) Clarendon Medium (CMC) **Gill SansTM1 (GSC) TYPESTYLE CHART (CON’T) Goudy Bold (GBO) *Optima Semi Bold (OSB) Goudy Extra Bold (GEB) Palatino (PAC) *Helvetica Bold (HBO) Palatino Italic (PAI) *Helvetica Bold Condensed (HBC) Radiant Bold Condensed (RBC) *Helvetica Medium (HMC) Rockwell BoldTM1 (RBO) **Helvetica Regular (HRC) Rockwell MediumTM1 (RMC) Highway Gothic B (HGC) Sabon Bold (SBC) ITC Isbell Bold®2 (IBC) *Standard Extended Medium (SEM) Jenson Medium (JMC) Stencil Gothic (SGC) Kestral Connected (KCC) Times Bold (TBC) Koloss (KOC) Time New Roman (TNR) Lectura Bold (LBC) *Transport Heavy (THC) Marker (MAC) Univers 57 (UN5) Melior Semi Bold (MSB) *Univers 65 (UNC) *Monument Block (MBC) *Univers 67 (UN6) Narrow Full Block (NFB) *V.A.G. -

Gourmet Typography Training

presents GOURMET TYPOGRAPHY TRAINING Take control of your type instead of letting it control you! Gourmet Typography Training teaches and demonstrates the expert-level typographic skills and aesthetics that are rarely taught in schools or fully understood by professionals. Fill in the gaps in your typographic know-how and learn how to “see” type like you’ve never seen it before. Why Gourmet Typography Training? Every creative professional, regardless of specialty, can benefit from learning to communicate more effectively with type. Whether you are a beginner or seasoned pro, Gourmet Typography Training will sharpen your eye and give you practical, usable skills that will visibly improve the beauty, clarity and effectiveness of all your typographic projects. Subjects covered include: Who will benefit? What makes a good typeface Visual communicators of all kinds, including: OpenType demystified Graphic designers Type crimes: Are you a type criminal? Art directors Fine-tuning type, including alignment, Creative directors hyphenation, hung punctuation, etc. Creative services directors Tracking, kerning, and word spacing Web designers Tips for more professional typography Package designers Type on the Web, Web fonts Production specialists Type in motion Typographers Keyboard shortcuts and time-saving tips Web programmers and developers Every creative professional regardless of specialty can learn to communicate more effectively with type! For more information, call The Type Studio at 203.227.5929 or email us at [email protected]. www.thetypestudio.com (page 1 of 2) What they are saying about Ilene’s Gourmet Typography Training... “Your course was great! Since taking it, “I recently attended your Gourmet “As a working professional in the advertis- I can’t help but look at every book title, Typography workshop and wanted to ing industry with 10 years of creative magazine headline, and even company thank you again for an amazing day. -

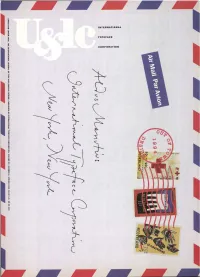

INTERNATIONAL TYPEFACE CORPORATION, to an Insightful 866 SECOND AVENUE, 18 Editorial Mix

INTERNATIONAL CORPORATION TYPEFACE UPPER AND LOWER CASE , THE INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF T YPE AND GRAPHI C DESIGN , PUBLI SHED BY I NTE RN ATIONAL TYPEFAC E CORPORATION . VO LUME 2 0 , NUMBER 4 , SPRING 1994 . $5 .00 U .S . $9 .90 AUD Adobe, Bitstream &AutologicTogether On One CD-ROM. C5tta 15000L Juniper, Wm Utopia, A d a, :Viabe Fort Collection. Birc , Btarkaok, On, Pcetita Nadel-ma, Poplar. Telma, Willow are tradmarks of Adobe System 1 *animated oh. • be oglitered nt certain Mrisdictions. Agfa, Boris and Cali Graphic ate registered te a Ten fonts non is a trademark of AGFA Elaision Miles in Womb* is a ma alkali of Alpha lanida is a registered trademark of Bigelow and Holmes. Charm. Ea ha Fowl Is. sent With the purchase of the Autologic APS- Stempel Schnei Ilk and Weiss are registimi trademarks afF mdi riot 11 atea hmthille TypeScriber CD from FontHaus, you can - Berthold Easkertille Rook, Berthold Bodoni. Berthold Coy, Bertha', d i i Book, Chottiana. Colas Larger. Fermata, Berthold Garauannt, Berthold Imago a nd Noire! end tradematts of Bern select 10 FREE FONTS from the over 130 outs Berthold Bodoni Old Face. AG Book Rounded, Imaleaa rd, forma* a. Comas. AG Old Face, Poppl Autologic typefaces available. Below is Post liedimiti, AG Sitoploal, Berthold Sr tapt sad Berthold IS albami Book art tr just a sampling of this range. Itt, .11, Armed is a trademark of Haas. ITC American T}pewmer ITi A, 31n. Garde at. Bantam, ITC Reogutat. Bmigmat Buick Cad Malt, HY Bis.5155a5, ITC Caslot '2114, (11 imam. -

The Anatomy of Type the ANATOMY of TYPE

The Anatomy of Type THE ANATOMY OF TYPE Stem Bars Serifs Leg Cap Height X Height Baseline Ascender Line X Height Descender Line Bowl Counter Ascender Shoulder Descender THE ANATOMY OF TYPE Mrs. Eaves Bembo Baskerville All of the above typefaces are set at 60 pt. You can see that each of the typefaces has a different X-Height and Cap Height. This will make each typeface read a bit differently and require each be set individually for optimal legibility. Typographic Terminology TYPOGRAPHIC TERMINOLOGY Font/Weight Adobe Garamond Pro Regular Adobe Garamond Pro Italic Adobe Garamond Pro Bold Adobe Garamond Pro Bold Italic The above is an example of a typeface. It is a family called a typeface while the members of the family are of different weights of the same typeface. This is a referred to as fonts. small family with only four weights. The family is TYPOGRAPHIC TERMINOLOGY Some typefaces have a much more extensive family of fonts. Above is a screen grab of the available fonts for Bembo. TYPOGRAPHIC TERMINOLOGY Ligatures fl ffl fi ffi Th fj ffjctst A ligature occurs where two or more characters are called “contextual forms” where the specific shape joined as a single glyph. Ligatures usually replace of a letter depends on context such as surrounding consecutive characters sharing common compo- letters. nents and are part of a more general class of glyphs TYPOGRAPHIC TERMINOLOGY Type Size Adobe Caslon Pro 6 pt. Adobe Caslon Pro 10 pt. Adobe Caslon Pro 14 pt. Adobe Caslon Pro 18 pt. Adobe Caslon Pro 24 pt. -

Does Font Type Has Effects on Web Text Readability?

International Education Studies; Vol. 6, No. 3; 2013 ISSN 1913-9020 E-ISSN 1913-9039 Published by Canadian Center of Science and Education Reading on the Computer Screen: Does Font Type has Effects on Web Text Readability? Ahmad Zamzuri Mohamad Ali1, Rahani Wahid1, Khairulanuar Samsudin1 & Muhammad Zaffwan Idris1 1 Faculty of Art, Computing & Creative Industry, Universiti Pendidikan Sultan Idris, Perak, Malaysia Correspondence: Ahmad Zamzuri Mohamad Ali, Faculty of Art, Computing & Creative Industry, Universiti Pendidikan Sultan Idris, Tanjong Malim, 35900, Perak, Malaysia. Tel: 60-124-777-395. E-mail: [email protected] Received: January 9, 2013 Accepted: January 18, 2013 Online Published: January 23, 2013 doi:10.5539/ies.v6n3p26 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.5539/ies.v6n3p26 Abstract Reading on the World Wide Web has become a daily habit nowadays. This can be seen from the perspective of changes on readers’ tendency to be more interested in materials from the internet, than the printed media. Taking these developments into account, it is important for web-based instructional designers to choose the appropriate font, especially for long blocks of text, in order to enhance the level of students’ readability. Accordingly, this study aims to evaluate the effects of serif and san serif font in the category of screen fonts and print fonts, in terms of Malay text readability on websites. For this purpose, four fonts were selected, namely Georgia (serif) and Verdana (san serif) for the first respondents and Times New Roman (serif) and Arial (san serif) for the second respondents. Georgia and Verdana were designed for computer screens display. -

„Bitstream“ Fonts

Key to the „Bitstream“ Fonts The history of typefaces is the history of forgeries. One of the greatest forgers of the 20th century was Matthew Carter. The Bitstream website (http://www.myfonts.com) describes him as follows: Matthew Carter of United Kingdom. Born: 1937 Son of Harry Carter, Royal Designer for Industry, contemporary British type designer and ultimate craftsman, trained as a punchcutter at Enschedé by Paul Rädisch, responsible for Crosfield's typographic program in the early 1960s, Mergenthaler Linotype's house designer 1965-1981. Carter co-founded Bitstream with Mike Parker in 1981. In 1991 he left Bitstream to form Carter & Cone with Cherie Cone. In 1997 he was awarded the TDC Medal, the award from the Type Directors Club presented to those „who have made significant contributions to the life, art, and craft of typography“. Carter’s „significant contribution to the life, art, and craft of typography“ consisted of forging the Linotype typeface collection. Carter can be characterized as a split personality. On the one hand, he has designed several original typefaces. On the other hand, he has forged hundreds of fonts. The following lists reveal that ca. 90% of the „Bitstream“ fonts are forgeries of the fonts contained in the catalog „LinoTypeCollection 1987“ („Mergenthaler Type Library“), i.e. the „Bitstream“ fonts are „nefarious evil knock-off clones“ (Bruno Steinert) of fonts sold by Linotype in the mid-1980s.1 „L“ in the following lists denotes that the font is contained in the „LinoTypeCollection 1987“. In the mid-1980s, the Linotype library comprised hundreds of typefaces with a total of 1700 fonts. -

Franklin Gothic: from Benton to Berlow

NUMBER TWO Franklin Gothic: from Benton to Berlow Sans serif, or gothic, typefaces became popular for advertising and promotional work in 19th century America. Their bold letterforms, brassy characteristics and efficient use of space were sought after then, just as they are now. By the time American Type Founders (ATF) was formed in 1892, more than 50 different sans serif faces were offered by the major American type suppliers. First Franklin Designs The Franklin Gothic™ typeface was the third in a series of sans serif faces designed after ATF was founded. In the early 1900s, Morris Fuller Benton, who was in charge of typeface development for ATF at the time, began to create the type designs that would influence American type design for more than 40 years. Globe Gothic was his first sans serif design, which was followed shortly thereafter by Alternate Gothic. Around 1902, Franklin Gothic was cut, although it was not released as a font of metal type until 1905. As he designed Franklin Gothic, Benton was likely influenced by the earlier sans serif designs released in Germany. Berthold had issued the Akzidenz Grotesk® series of typefaces (later known to American printers as “Standard”) in 1898. Akzidenz Grotesk inspired the cutting of Reform Grotesk by the Stempel foundry of Frankfurt in 1903, and the Venus™ series of typefaces by the Bauer foundry, also of Frankfurt, in 1907. A Small Family At first, Benton drew only a single roman design for Franklin Gothic. However, this typeface caught the imagination of printers of the time, and ATF was compelled to add more variants to make a small type family. -

Haw U Haw U Haw U Haw U Haw U Haw U Awuawu

a a a a a a U U U U U U U U U U W W W W W W H H H H aW W aW W a H aW W a H H H HaW W a HH aW W a HH aW W H H H H H H W W W W W W a a a a U U a a U U U U U U U U U U U U U U U U U U a a a a a a W W W W W W H H H H H H aW W a H H aW W a H H W a W a HH H aW W a HH aW W a H H H H H H H W W W W W W a a a a a a U U U U U U U U U U U U U U U U U U U a a U a a a a W W W W W W A VA N H H H H H H aW W a aW W a H H H H aW W HaW W a HH aW W a HH aW W H H GRDE W W W W U U U U U W W U U U U U a a a a a a “the advanced, the innovative, the creative” – Ralph Ginzburg Avant Garde was never intended to However, the magazine is most notable be a commercial font. Rather, it’s first for the logogram that Lubalin created.