Paul Chaat Smith

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

C a H U I L L A

C A H U I L L A Sculpture by Lewis deSoto C A H U I L L A Sculpture by Lewis deSoto Essay by Nick Stone Published by sotolux press ©2006 Lewis deSoto, CAHUILLA, customized truck, Jacquard tapestry, sound and lighting system, Installation at the Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum, Ridgefield, CT, 2006 Photograph by Terri Garneau 360 Lb.-ft. One Ton Mash-up Lewis deSoto’s Cahuilla is a product of the surreal, poetic simultaneity found in dreams, a manifestation in three gleaming dimensions of the rhizomatic “and… and… and…” idiom which Deleuze and Guattari declared muscular enough to wrestle with ontology itself. One imagines a dreamer’s breathless description to a bemused companion upon awakening: “It was an enormous truck, painted with the colors of the desert… and it was also kind of a giant dollar bill, with the same lettering and symbols that money has… and it was also a casino – there was a woven craps table on the back and I could see the slot machine lights and hear the dealers… and at the same time, the dealers’ voices were chanting in Cahuilla… it was unbelievable.” Too, like a dream, Cahuilla is a vehicle capable of taking its passenger on a ride that is both sensual and conceptual; many of the components in its sequence of familiar forms are themselves transitive, stealthily piloted by an interior significance. In elements ranging from luxurious aluminum customizations to traditional beaded and woven motifs and a hybridized soundtrack, deSoto refers to a singular convergence of indigeneous tradition, newfound economic prosperity, a distinctly regional form of reified self- expression and the practical needs of desert survival. -

Faculty San Francisco State University Bulletin 2020-2021

Faculty San Francisco State University Bulletin 2020-2021 MICHAEL ALBERT (1977), Professor of Management; B.A. (1972), State FACULTY University of New York, Albany; M.B.A. (1974), Ph.D. (1977), Georgia State University. • # • A (p. 1) OLIVIA ALBIERO (2016), Assistant Professor of Modern Languages and Literatures; B.A. (2006), M.A. (2008), University of Padua; M.A. (2011), • B (p. 2) Ph.D. (2016), University of Washington. • C (p. 4) • D (p. 6) MICHELLE ALEGRIA-HARTMAN (2004), Adjunct Professor of Biology; B.A. • E (p. 8) (1982), University of California, Berkeley; B.S. (1985), M.A. (1993), San Francisco State University; Ph.D. (2002), University of California, Davis. • F (p. 8) • G (p. 9) ABEER ALJARRAH (2018), Assistant Professor of Computer Science; • H (p. 11) B.Sc. (2005) Jordan University of Science and Technology, M.Sc. • I (p. 13) (2010), Yarmouk University; Ph.D. (2018), University of North Carolina at Charlotte. • J (p. 13) • K (p. 14) DIANE ALLEN (2008), Professor of Physical Therapy; B.S. (1978), University • L (p. 15) of California, San Francisco; M.S. (1991), University of North Carolina, • M (p. 18) Chapel Hill; Ph.D. (2005), University of California, Berkeley. • N (p. 20) GWEN ALLEN (2007), Professor of Art; B.A. (1994), Smith College; M.A. • O (p. 20) (1999), Stanford University; Ph. D (2004), Stanford University. • P (p. 21) SARAH ALLEN (2004), Adjunct Professor of Biology; • Q (p. 22) • R (p. 22) FRANK ALMEDA (1998), California Academy of Sciences Research • S (p. 24) Professor, Adjunct Professor of Biology; B.A. (1968), University of South Florida; Ph.D. -

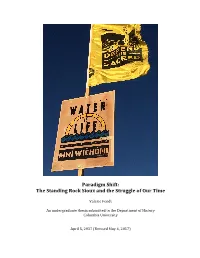

Paradigm Shift: the Standing Rock Sioux and the Struggle of Our Time

Paradigm Shift: The Standing Rock Sioux and the Struggle of Our Time Valerie Fendt An undergraduate thesis submitted to the Department of History Columbia University April 5, 2017 (Revised May 4, 2017) Table of Contents Page 3 Acknowledgements Page 4 Introduction Page 9 Chapter One: The Shifting Dispositions of Settler Colonialism Page 26 Chapter Two: From Resistance to Resurgence Page 42 Chapter Three: The Standing Rock Sioux and the Struggle of Our Time Page 57 Conclusion Page 59 Notes Page 72 Bibliography 2 Acknowledgements As a student who has had the great fortune to study at Columbia University I would like to recognize, honor, and thank the Lenni-Lenape people upon whose land this university sits and I have had the freedom to roam. I am indebted to the Indigenous scholars and activists who have shared their knowledge and made my scholarship on this subject what it is. All limitations are strictly my own, but for what I do know I am indebted to them. I am grateful to all of the wonderful people I met at Standing Rock in October of 2016. I can best describe the experience as a gift I will carry with me always. Thank you to the good people of the “solo chick warrior camp,” to Vanessa for inviting us in, to Leo for giving me the chance to employ usefulwhiteallyship, to Alexa for the picture that adorns this cover. I would like to thank the history professors who have given so generously of their time, who have invested their energy and their work to assist my academic journey, encouraged my curiosity, helped me recognize my own voice, and believed it deserved to be heard. -

The American Indian Movement, the Trail of Broken Treaties, and the Politics of Media

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Dissertations, Theses, & Student Research, Department of History History, Department of 7-2009 Framing Red Power: The American Indian Movement, the Trail of Broken Treaties, and the Politics of Media Jason A. Heppler Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/historydiss Part of the History Commons Heppler, Jason A., "Framing Red Power: The American Indian Movement, the Trail of Broken Treaties, and the Politics of Media" (2009). Dissertations, Theses, & Student Research, Department of History. 21. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/historydiss/21 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the History, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, & Student Research, Department of History by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. FRAMING RED POWER: THE AMERICAN INDIAN MOVEMENT, THE TRAIL OF BROKEN TREATIES, AND THE POLITICS OF MEDIA By Jason A. Heppler A Thesis Presented to the Faculty The Graduate College at the University of Nebraska In Partial Fulfillment of Requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts Major: History Under the Supervision of Professor John R. Wunder Lincoln, Nebraska July 2009 2 FRAMING RED POWER: THE AMERICAN INDIAN MOVEMENT, THE TRAIL OF BROKEN TREATIES, AND THE POLITICS OF MEDIA Jason A. Heppler, M.A. University of Nebraska, 2009 Adviser: John R. Wunder This study explores the relationship between the American Indian Movement (AIM), national newspaper and television media, and the Trail of Broken Treaties caravan in November 1972 and the way media framed, or interpreted, AIM's motivations and objectives. -

Finding Critical and Gradient-Flat Points of Deep Neural Network Loss Functions

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Finding Critical and Gradient-Flat Points of Deep Neural Network Loss Functions Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/4fw6x5b3 Author Frye, Charles Gearhart Publication Date 2020 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Finding Critical and Gradient-Flat Points of Deep Neural Network Loss Functions by Charles Gearhart Frye A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Neuroscience in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Associate Professor Michael R DeWeese, Co-chair Adjunct Assistant Professor Kristofer E Bouchard, Co-chair Professor Bruno A Olshausen Assistant Professor Moritz Hardt Spring 2020 Finding Critical and Gradient-Flat Points of Deep Neural Network Loss Functions Copyright 2020 by Charles Gearhart Frye 1 Abstract Finding Critical and Gradient-Flat Points of Deep Neural Network Loss Functions by Charles Gearhart Frye Doctor of Philosophy in Neuroscience University of California, Berkeley Associate Professor Michael R DeWeese, Co-chair Adjunct Assistant Professor Kristofer E Bouchard, Co-chair Despite the fact that the loss functions of deep neural networks are highly non-convex, gradient-based optimization algorithms converge to approximately the same performance from many random initial points. This makes neural networks easy to train, which, com- bined with their high representational capacity and implicit and explicit regularization strategies, leads to machine-learned algorithms of high quality with reasonable computa- tional cost in a wide variety of domains. One thread of work has focused on explaining this phenomenon by numerically character- izing the local curvature at critical points of the loss function, where gradients are zero. -

“To Awaken a Nation Asleep”: Community Building Amid Radical Activism, and the Indian Alcatraz Occupation

“To awaken a nation asleep”: Community Building Amid Radical Activism, and the Indian Alcatraz Occupation by R. Zöe Costanzo A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Affairs in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in English Language and Literature Carleton University Ottawa, Ontario © 2016 R. Zöe Costanzo ii ABSTRACT This thesis examines events leading to and during the Indian occupation of Alcatraz Island of 1969-1971. While scholars have used the occupation as an example of the changing trajectory of American Indian activism in the late 20th century, especially in regards to the American Indian Movement and Red Power Movement, the event is rarely examined on its own terms. This thesis seeks to fill that gap, focusing on concrete community building initiatives both on and around the island between 1964 and 1971. In doing so, it argues that Alcatraz was not only a symbolic space of Indian freedom, but also a physical place where Indians’ lives were changed, and Indians’ futures were informed. The thesis brings to bear significant archival research from the National Parks Service Records and Collections, public collections in San Francisco, CA, where many occupiers have preserved their occupation accounts and photographs. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Many have lent their voices to this project throughout its duration. First and foremost, I would like to thank Dr. Franny Nudelman, who introduced and patiently guided me through the genre of narrative history. It was Dr. Nudelman who encouraged the overambitious and ever- expanding project I proposed, and who then provided the knowledge and guidance necessary for its realization. -

Accelerated Reader Book List

Accelerated Reader Book List Picking a book to read? Check the Accelerated Reader quiz list below and choose a book that will count for credit in grade 7 or grade 8 at Quabbin Middle School. Please see your teacher if you have questions about any selection. The most recently added books/tests are denoted by the darkest blue background as shown here. Book Quiz No. Title Author Points Level 8451 EN 100 Questions and Answers About AIDS Ford, Michael Thomas 7.0 8.0 101453 EN 13 Little Blue Envelopes Johnson, Maureen 5.0 9.0 5976 EN 1984 Orwell, George 8.2 16.0 9201 EN 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea Clare, Andrea M. 4.3 2.0 523 EN 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (Unabridged) Verne, Jules 10.0 28.0 6651 EN 24-Hour Genie, The McGinnis, Lila Sprague 4.1 2.0 593 EN 25 Cent Miracle, The Nelson, Theresa 7.1 8.0 59347 EN 5 Ways to Know About You Gravelle, Karen 8.3 5.0 8851 EN A.B.C. Murders, The Christie, Agatha 7.6 12.0 81642 EN Abduction! Kehret, Peg 4.7 6.0 6030 EN Abduction, The Newth, Mette 6.8 9.0 101 EN Abel's Island Steig, William 6.2 3.0 65575 EN Abhorsen Nix, Garth 6.6 16.0 11577 EN Absolutely Normal Chaos Creech, Sharon 4.7 7.0 5251 EN Acceptable Time, An L'Engle, Madeleine 7.5 15.0 5252 EN Ace Hits the Big Time Murphy, Barbara 5.1 6.0 5253 EN Acorn People, The Jones, Ron 7.0 2.0 8452 EN Across America on an Emigrant Train Murphy, Jim 7.5 4.0 102 EN Across Five Aprils Hunt, Irene 8.9 11.0 6901 EN Across the Grain Ferris, Jean 7.4 8.0 Across the Wide and Lonesome Prairie: The Oregon 17602 EN Gregory, Kristiana 5.5 4.0 Trail Diary.. -

Subaltern Resistance and Wounded Knee, 1973 Nathan Sell University of Nebraska at Kearney

Undergraduate Research Journal Volume 20 Article 10 2016 Subaltern Resistance and Wounded Knee, 1973 Nathan Sell University of Nebraska at Kearney Follow this and additional works at: https://openspaces.unk.edu/undergraduate-research-journal Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Sell, Nathan (2016) "Subaltern Resistance and Wounded Knee, 1973," Undergraduate Research Journal: Vol. 20 , Article 10. Available at: https://openspaces.unk.edu/undergraduate-research-journal/vol20/iss1/10 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Office of Undergraduate Research & Creative Activity at OpenSPACES@UNK: Scholarship, Preservation, and Creative Endeavors. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Research Journal by an authorized editor of OpenSPACES@UNK: Scholarship, Preservation, and Creative Endeavors. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Subaltern Resistance and Wounded Knee, 1973 Nathan Sell American Indian resistance to Euro-American expansionism has long been considered under the purview of “American history.” This subsumption of indigenous perspectives within the limits and boundaries of an “American history” represents a, if not the, dominant raison d'être for considering indigenous histories in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. As such, indigenous history under this perspective is potentially seen as useful only in that it holds explanatory value in the context of an American history. No single event in the past four-hundred plus years shatters that aforementioned account -

Jan | Feb | March | 2020

jan | feb | march | 2020 SANTA BARBARA MUSEUM OF ART from the director Dear Members, Happy New Year! The year 2020 is truly one for celebrating! The Museum continues to present groundbreaking exhibitions, including that of Tatsuo Miyajima. On view through April 19, this exciting installation represents the artist’s first solo U.S. museum exhibition in over two decades and the rare opportunity to experience the captivating and immersive light-based work that embodies his Buddhist practice. In addition, a selection of small-format American paintings will grace a section of Ridley-Tree Gallery in later March, highlighting the important Preston Morton Collection of American art. This installation is an impressive reminder of the breadth of the Museum’s holdings in that area and includes beautiful works by Frederic Edwin Church, Thomas Eakins, Walter Gay, and William Merritt Chase, just to name a few. The ever-popular Parallel Stories Lecture Series returns with Pulitzer Prize-winning author Jane Smiley in February and former California and U.S. Poet Laureate Juan Felipe Herrera in March. In addition, Art Matters makes a comeback this winter season with engaging lectures by eminent scholars on the artists Michelangelo and Frederick Hammersley. Finally, this year marks the beginning of the countdown to the October 11 re-opening of SBMA’s galleries, which have been closed due to the current renovation project. This will be the first time that Members and visitors will have the opportunity to experience the extraordinary transformation of the Museum, including new dedicated exhibition spaces for contemporary art, photography, and new media; a breathtaking re- installation of Ludington Court; a new grand staircase; and refined finishes and state-of-the-art lighting. -

The Rock of Red Power: the 1969-1971 Occupation of Alcatraz Island Sarah Spalding Western Kentucky University, [email protected]

Western Kentucky University TopSCHOLAR® Honors College Capstone Experience/Thesis Honors College at WKU Projects Spring 5-9-2018 The Rock of Red Power: The 1969-1971 Occupation of Alcatraz Island Sarah Spalding Western Kentucky University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wku.edu/stu_hon_theses Part of the History Commons, Indigenous Studies Commons, and the Politics and Social Change Commons Recommended Citation Spalding, Sarah, "The Rock of Red Power: The 1969-1971 cO cupation of Alcatraz Island" (2018). Honors College Capstone Experience/ Thesis Projects. Paper 745. https://digitalcommons.wku.edu/stu_hon_theses/745 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by TopSCHOLAR®. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors College Capstone Experience/ Thesis Projects by an authorized administrator of TopSCHOLAR®. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE ROCK OF RED POWER: THE 1969-1971 OCCUPATION OF ALCATRAZ ISLAND A Capstone Project Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Bachelor of Arts in English Literature with Honors College Graduate Distinction at Western Kentucky University By Sarah D. Spalding May 2018 ***** Western Kentucky University 2018 CE/T Committee: Approved by Dr. Patricia Minter, Chair Dr. Alexander Olson ______________________________________ Dr. Andrew Rosa Advisor Department of History Copyright by Sarah D. Spalding 2018 ABSTRACT When over 90 Native Americans first made the voyage to Alcatraz Island on a November 1969 morning, there was little that could be predicted about what would unfold in the coming years. Alcatraz Island, the infamous prison that held criminals on the forefront of world news in the early twentieth century, would soon become an activist symbol. -

Self-Portrait), 1999–2015

Contact: Katrina Carl Public Relations Manager 805.884.6430 [email protected] Lewis deSoto, Paranirvana (Self-Portrait), 1999–2015. Painted vinyl infused cloth, electric air fan, 3rd in a series with color variations. Courtesy of Chandra Cerrito Contemporary. Lewis deSoto Paranirvana (Self-Portrait) Newly-Commissioned Work Breathes Life into Santa Barbara Museum of Art’s Historic Ludington Court On View April 17 – July 31, 2016 April 15, 2016―Lewis deSoto’s multi-media works are informed by the artist’s long-standing interest in anthropology, history, mythology, and religion. All are engaged in the artist’s forthcoming solo exhibition—an installation featuring his monumental scale, inflatable sculpture, Paranirvana (Self-Portrait) (1999–2015). Inspired by the 12th-century Buddha at Gal Vihara in Sri Lanka, and conceived in the wake of his father’s death, this work serves as not only a representation of universal life, death, and supreme consciousness; but also, embellished with features similar to the artist, a self-portrait. The 26-foot-long Paranirvana (Self-Portrait) is activated―or rather brought to life―with an industrial fan, which inflates (inhales) when switched on at the beginning of the day, and deflates (exhales) when switched off at closing. As such, the work provides allusions to the spiritual breath (Prana) in Hindu philosophy, prevalent in the common practice of yoga. Enormous yet ephemeral, witty yet also thought-provoking, Paranirvana (Self-Portrait) rouses reflections upon existence, loss, and spirituality. Paranirvana -

Music for Guitar

So Long Marianne Leonard Cohen A Bm Come over to the window, my little darling D A Your letters they all say that you're beside me now I'd like to try to read your palm then why do I feel so alone G D I'm standing on a ledge and your fine spider web I used to think I was some sort of gypsy boy is fastening my ankle to a stone F#m E E4 E E7 before I let you take me home [Chorus] For now I need your hidden love A I'm cold as a new razor blade Now so long, Marianne, You left when I told you I was curious F#m I never said that I was brave It's time that we began E E4 E E7 [Chorus] to laugh and cry E E4 E E7 Oh, you are really such a pretty one and cry and laugh I see you've gone and changed your name again A A4 A And just when I climbed this whole mountainside about it all again to wash my eyelids in the rain [Chorus] Well you know that I love to live with you but you make me forget so very much Oh, your eyes, well, I forget your eyes I forget to pray for the angels your body's at home in every sea and then the angels forget to pray for us How come you gave away your news to everyone that you said was a secret to me [Chorus] We met when we were almost young deep in the green lilac park You held on to me like I was a crucifix as we went kneeling through the dark [Chorus] Stronger Kelly Clarkson Intro: Em C G D Em C G D Em C You heard that I was starting over with someone new You know the bed feels warmer Em C G D G D But told you I was moving on over you Sleeping here alone Em Em C You didn't think that I'd come back You know I dream in colour