One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Congressional Record United States Th of America PROCEEDINGS and DEBATES of the 110 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 110 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION Vol. 153 WASHINGTON, TUESDAY, OCTOBER 30, 2007 No. 166 House of Representatives PRAYER lic for which it stands, one nation under God, indivisible, with liberty and justice for all. The House met at 9 a.m. and was The Chaplain, the Reverend Daniel P. called to order by the Speaker pro tem- Coughlin, offered the following prayer: f pore (Mr. SIRES). Lord God, we seek Your guidance and EFFECTS OF ALTERNATIVE f protection; yet, we are often reluctant MINIMUM TAX to bend to Your ways. Help us to under- DESIGNATION OF SPEAKER PRO (Mr. ISRAEL asked and was given stand the patterns of Your creative TEMPORE permission to address the House for 1 hand. In the miracle of life and the minute and to revise and extend his re- The SPEAKER pro tempore laid be- transformation to light, You show us marks.) fore the House the following commu- Your awesome wonder. Both the chang- Mr. ISRAEL. Madam Speaker, one of nication from the Speaker: ing seasons and the dawning of each the greatest financial assaults on WASHINGTON, DC, day reveal for us Your subtle but con- America’s middle class is the alter- October 30, 2007. sistent movement during every mo- native minimum tax. Originally, it was I hereby appoint the Honorable ALBIO ment of life. SIRES to act as Speaker pro tempore on this meant to ensure that several dozen of Without a screeching halt or sudden day. -

Razorcake Issue #09

PO Box 42129, Los Angeles, CA 90042 www.razorcake.com #9 know I’m supposed to be jaded. I’ve been hanging around girl found out that the show we’d booked in her town was in a punk rock for so long. I’ve seen so many shows. I’ve bar and she and her friends couldn’t get in, she set up a IIwatched so many bands and fads and zines and people second, all-ages show for us in her town. In fact, everywhere come and go. I’m now at that point in my life where a lot of I went, people were taking matters into their own hands. They kids at all-ages shows really are half my age. By all rights, were setting up independent bookstores and info shops and art it’s time for me to start acting like a grumpy old man, declare galleries and zine libraries and makeshift venues. Every town punk rock dead, and start whining about how bands today are I went to inspired me a little more. just second-rate knock-offs of the bands that I grew up loving. hen, I thought about all these books about punk rock Hell, I should be writing stories about “back in the day” for that have been coming out lately, and about all the jaded Spin by now. But, somehow, the requisite feelings of being TTold guys talking about how things were more vital back jaded are eluding me. In fact, I’m downright optimistic. in the day. But I remember a lot of those days and that “How can this be?” you ask. -

Family Matters: Public Policy and the Interdependence of Generations

Family Matters: Public Policy and the Interdependence of Generations Generations United Jatrice Martel Gaiter Staff Board of Directors Executive Vice President of External Donna M. Butts Affairs Chair Executive Director Volunteers of America William L. Minnix Ana Beltran President & CEO Irv Katz Special Advisor American Association of Homes and President & CEO National Center on Grandfamilies Services for the Aging National Human Services Assembly Leah Bradley Vice-Chair Karen Mathis Project Specialist Matthew Melmed President & CEO Executive Director Big Brothers Big Sisters of America Mary Coombs ZERO TO THREE Office Assistant Lawrence McAndrews Treasurer President & CEO Jaia Peterson Lent Christine James-Brown National Association of Children’s Deputy Executive Director President & CEO Hospitals & Related Institutions Halina Manno Child Welfare League of America Larry Naake Finance & Operations Manager Secretary Executive Director Roxana Martinez Michael S. Marcus National Association of Counties Program Coordinator Program Officer John Rother The Harry and Jeanette Weinberg Foun - Melissa Ness Executive Vice President, Policy & Strategy dation Public Policy Coordinator AARP Board Members Eliseba Osore Paul N. D. Thornell Project Assistant MaryLee Allen Vice President, Federal Government Director Affairs, Citigroup Inc. Rich Robinson Child Welfare and Mental Health Press Secretary Children’s Defense Fund Sandra Timmerman Director Shelton Roulhac William H. Bentley MetLife Mature Market Institute Policy Analyst President & CEO Sheri -

1935-06-06.Pdf

'Avjy‘; n ! i j f f A''Vv\ .vW H i! fx vv: PRODUCE PANY ... AND BUY »P*imtor fo r ax ) a w eek. Llb- l a h t f c a l e r allowancea on P h o n e S7R2 SIXTY-FIRST YEAR CHATSWORTH. ILUNOIS. THURSDAY. JUNE 6. 1935 NO. 39 V.THEIRS. Mgr. t OFF WITH THE OLD, ON WITH THE NEW tMMBMMNBNBM COMMENCEMENT H O T SLUGS EDIGRAPHS DEATH CLOSES At time* like these the av Once It was "Brother, can AND PICNIC OF erage man would rather be you spare a dime," Now It’s THECAKEEXOF almost anything else than "Uncle, slip us a couple mil LOCALSCHOOLS president. lion.” . 0E0. STROBEL Store The old-time family doctor Every year makes us safer. had one advantage. He knew When the country washes or Rev. J. W. R. Maguire you so well he could tell oth blows away, the Japs won’t Long-time Business Man la er symptoms from scare. want It. Gives Inspiring Address Victim of Uremic News from the dust storm Why worry? If an idea _ $1.98 to Graduates. country: Housewives are proves sour, the government Poisoning. leaving flower boxes In the always drops It before it $2.98 garage this spring and seed costs over a billion or so. Friday, May 31st, was an ap George Strobel died at his homa ing the window sills. propriately crowded day to wind It does seem sort of silly in Chatsworth at 8 o'clock Satur ___ 98<f up a crowded school year. -

Supplementary Materials

Experiment 1 Accidentally the young woman snubbed the acquaintance/*vinegar… Accidentally the young woman packed the vinegar/*acquaintance… After clearing the table at the diner the busboy thanked the cook/*pots… After clearing the table at the diner the busboy rinsed the pots/*cook… After feeding the infant the parent burped the tot/*cloth… After feeding the infant the parent unbuttoned the cloth/*tot… After getting his last card the high roller deceived the gambler/*money… After getting his last card the high roller hurled the money/*gambler… After heavy snowfalls in winter the old man thanked the groundskeeper/*stairs… After heavy snowfalls in winter the old man salted the stairs/*groundskeeper… After her son left for boarding school the mother praised the lad/*toys… After her son left for boarding school the mother stored his toys/*lad… After his daughter left the church the priest shunned the boyfriend/*tradition… After his daughter left the church the priest reiterated the tradition/*boyfriend… After much deliberation the university president appointed the director/*campus… After much deliberation the university president expanded the campus/*director… After school was out for the day the janitor insulted the superintendent/*cafeteria… After school was out for the day the janitor mopped the cafeteria/*superintendent… After she had been married for five years the woman divorced the deadbeat/*post… After she had been married for five years the woman resumed the post/*deadbeat… After soccer practice was over the player invited the teammate/*decision… -

Banker-Lawer- and Commercialized Thru- Pany Sending Let Us Your Men out to Resident Sec- Tro

6 IMPERIAL VALLEY PRESS,JANUARY 2«. 1920 Ann fIHMi 'from the icebox and is cut with a “low Haetfl.- *l»» A (Ml Refining tVv, Ran .¦utter’’ cutter, which eouts one cube, l%fn. ' >r about 04 pounds, with one move- VICE PROBE PAVING PROBLEM The rultoinitrk' Kl Centro. l.nent. The butter is then wrapped in Theatre I Hunon.l I tar (HI Co.. Culipatria. l,K>und packages and repacked in the Palace one) (Continued pa.ee from ImtuTMl Valiev (HI Syndicate, I,os (cubes, which are afterward replaced (mi >»¦ Tonight—Two Shows 7 and 9. in the icebox until it can be shipped '¦every sort of gambling equipment was California Imperial HjriHßnit*, I>m> to the consumer. LAST DAY TO SEE (iHdw, in full swing:. IS SERIOOS ONE The Colorado IVent (HI A (Inn Com- building * In Calexico one 50x100 on puny. Brawny. I Seventh street, called the Los Palmas, DOUGLAS Mt Ml«na| (HI (V. Calexico. FAIRBANKS in Mexicans, produced 20 .Taps, Hindus H. L A K. (Ml Co„ la>i* Angeles. and white men. The boss had SIOO in Yuma Rnain (Ml (*o„ Kl (Vntro. CALEXICO AND silver cashing in for the crowd. SAYS ENGINEER “When the Clouds Roll By” Vhlw (HI (’#., Han Dtegp. The Hotel De Luxe, Los Angeles U Moan* (Ml (M, Him IMnito. The rooming house, Best Picture Fairbanks Ever Made The Russell house and The (oltimn* of the Press »re The Cinopuw Oi, Man Diego. places. 50c.; Children several smaller open at all times for the The llolliugavrorth (HI IV. Admission. Adults 11c. -

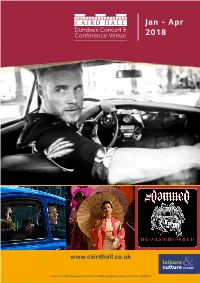

Jan - Apr 2018

Jan - Apr 2018 www.cairdhall.co.uk Leisure & Culture Dundee is a Scottish Charitable Incorporated Organisation No. SC042421 DIARY OF EVENTS January 2018 page Saturday 13 Mohsen Amini and Craig Irving 18 Sunday 14 Jean Johnson, Naomi and Fali Pavri 19 Wednesday 24 ELO Experience 4 Friday 26 Some Guys have All The Luck 4 Saturday 27 The Damned 5 Sunday 28 Mary McInroy 18 February 2018 Thursday 1 Steven Osborne Piano Recital 6 Friday 2 Erasure - SOLD OUT 6 Sunday 4 CD & Records Fair 19 Saturday 10 The Big Dundee Wedding Exhibition 7 Sunday 11 The Big Dundee Wedding Exhibition 7 Thursday 15 RSNO - Brief Encounter Live 7 Friday 23 Scottish National Jazz Orchestra 8 Saturday 24 The Elvis Years 9 Sunday 25 Dundee Gaelic Choir 18 March 2018 Saturday 3 Children's Classic Concerts - Tartan Tales 9 Sunday 4 CD & Records Fair 19 Wednesday 14 Rock Challenge Heats 10 Thursday 15 RSNO - Søndergård Conducts Ein Heldenleben 10 Friday 16 Scottish Ensemble - Court & Country 11 Sunday 18 Dundee Choral Union 11 Thursday 22 The Castalian Quartet 19 Friday 23 Big Girls Don’t Cry 12 Sunday 25 Dundee University Music Society 12 Tuesday 27 High School of Dundee Spring Concert 14 Friday 30 Rumours of Fleetwood Mac 13 Saturday 31 Dundee Symphony Orchestra 14 Kenzie Photography Kenzie April 2018 c Sunday 1 Madama Butterfly 15 ©James M Thursday 12 The Chicago Blues Brothers 16 Friday 20 Gary Barlow - SOLD OUT 16 Saturday 28 Seven Drunken Nights - The Story of the Dubliners 17 2 www.dundeebox.co.uk dundee city box office 01382434940 WELCOME Spring is in the air and with it, a packed brochure of Concerts some new, some sold out and some returning favourites. -

Summer 2019 · Free

news in natural SUMMER 2019 · FREE Visit GeerCrest Farm A Willamette Homestead Classroom Turf to Ecosystem · Summer Recipes · What’s in Season at LifeSource? Contact Us General Manager Alex Beamer [email protected] Store Manager Jeff Watson [email protected] Grocery & Perishables Marie Wallace [email protected] Bulk Joyce DeGaetano See Tiara’s recipe for Cool Lime Pie on page 21 [email protected] Produce Cicadas are buzzing in the trees outside my window, and the Jimmy Vaughn kids are grazing for berries in the garden. After months of [email protected] rain, chill, and bare branches, I’m always surprised to find myself here again, in the land of summer, beneath lush green Beer & Wine leaves and the blue dome of the sky, sweat trickling down the Liam Stary backs of my knees. [email protected] As anyone who has seen my yard knows, I aim for more Wellness Kathy Biskey of an untended woodland glade aesthetic than the more [email protected] typical manicured lawn, so I’m pleased to read Savanna’s encouragement to diversify our yards and bring in native and Deli wildlife-friendly plants. Also in this issue of News in Natural, Eric Chappell GeerCrest Farm introduces us to their unique educational [email protected] farm, steeped in history and environmental stewardship. Zira explores the risks posed by certain sunscreens and shows Mercantile · Health & Beauty us how to identify safe options. As always, the LifeSource Zira Michelle Brinton team fills us in on their favorites and some of the new items [email protected] throughout the store, and shares some of their favorite beat- the-heat recipes. -

Congressional Record United States Th of America PROCEEDINGS and DEBATES of the 104 CONGRESS, SECOND SESSION

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 104 CONGRESS, SECOND SESSION Vol. 142 WASHINGTON, FRIDAY, JULY 26, 1996 No. 112 House of Representatives The House met at 9 a.m. [Roll No. 366] Rohrabacher Serrano Talent The Chaplain, Rev. James David Ros-Lehtinen Shadegg Tanner YEASÐ229 Roth Shaw Tate Ford, D.D., offered the following pray- Roukema Shays Tauzin Ackerman Diaz-Balart Kleczka Roybal-Allard Shuster Thornberry er: Allard Dingell Klink Royce Sisisky Thurman At the beginning of each day we give Andrews Dooley Kolbe Rush Skaggs Traficant Archer Dreier LaHood thanks to you, O God, for all the gifts Salmon Skeen Upton Armey Duncan Lantos and blessings and hopes that we re- Sanford Smith (MI) Walker Bachus Edwards Latham Sawyer Smith (TX) Walsh ceive. As the scriptures proclaim, Baesler Ehrlich Levin Saxton Smith (WA) Wamp ``Make a joyful noise to the Lord, all Baldacci Eshoo Lewis (CA) Schaefer Solomon Ward Ballenger Farr Lightfoot the lands! Serve the Lord with glad- Schiff Stark Wicker ness! Come into his presence with sing- Barcia Fattah LoBiondo Schumer Stearns Williams Barr Flake Lucas ing!'' It is our earnest prayer, O God, Scott Stenholm Woolsey Barrett (NE) Flanagan Luther Sensenbrenner Stump that whatever our circumstance or Barrett (WI) Foley Maloney whatever our situation, whatever our Bartlett Forbes Manton NAYSÐ51 Bass Franks (CT) Martini opportunity, we will respond to this Abercrombie Hefley Pallone Bateman Franks (NJ) Mascara Borski Heineman Payne (NJ) day with prayer, praise, and thanks- Bentsen Frelinghuysen Matsui Clay Hilleary Pickett Bilbray Frisa McCarthy giving. -

PRESSEMITTEILUNG 18.01.2018 the Damned Im Mai in Deutschland

FKP Scorpio Konzertproduktionen GmbH Große Elbstr. 277 a ∙ 22767 Hamburg Tel. (040) 853 88 888 ∙ www.fkpscorpio.com PRESSEMITTEILUNG 18.01.2018 The Damned im Mai in Deutschland 40 Jahre Punk. Reiner, purer Punk. Zumindest zu Beginn: The Damned waren von Anfang an dabei, haben alles gesehen, haben in jedem Rattenloch der britischen Inseln ihren rohen Rock’n’Roll gespielt, beeinflusst von den Stooges und den MC5. Sie waren die erste Band, die eine Punk-Single veröffentlicht hat, 1976, „New Rose“, und sie haben mit „Damned Damned Damned“ auch das erste Album aufgenommen. Sie waren die ersten, die ihr Sound-Spektrum erheblich erweiterten und sich beispielsweise dem Goth öffneten und mit der Coverversion „Eloise“ unglaublich erfolgreich waren (ganz abgesehen von Captain Sensible, der mit dem Rap-Song „Wot“ fast aus Versehen die Charts stürmte. Aber das ist eine andere Geschichte). Und sie stehen seit über 40 Jahren fast ohne Unterbrechung auf der Bühne. Anders gesagt: The Damned sind eine verdammte Legende. Vor allem aber sind Sänger Dave Vanian, Gitarrist Captain Sensible, Bassist John Priestley, Keyboarder Monty Oxymoron und Schlagzeuger Pinch Pinching immer noch in der Lage große Songs zu produzieren. Eben erschien mit „Standing On The Edge Of Tomorrow“ der erste Vorgeschmack auf das kommende Album „Evil Spirits“, im Mai folgt dann die große Deutschland-Tour. Präsentiert wird die Tour von Ox-Fanzine & livegigs.de, Orkus! Magazin und laut.de. 17.05.2018 Frankfurt - Batschkapp 22.05.2018 München - Strom 23.05.2018 Berlin - SO 36 25.05.2018 Hamburg - Fabrik 26.05.2018 Oberhausen - Turbinenhalle (im Rahmen der New Waves Day) Tickets für die Clubshows gibt es ab Freitag, den 19. -

The Dictionary Legend

THE DICTIONARY The following list is a compilation of words and phrases that have been taken from a variety of sources that are utilized in the research and following of Street Gangs and Security Threat Groups. The information that is contained here is the most accurate and current that is presently available. If you are a recipient of this book, you are asked to review it and comment on its usefulness. If you have something that you feel should be included, please submit it so it may be added to future updates. Please note: the information here is to be used as an aid in the interpretation of Street Gangs and Security Threat Groups communication. Words and meanings change constantly. Compiled by the Woodman State Jail, Security Threat Group Office, and from information obtained from, but not limited to, the following: a) Texas Attorney General conference, October 1999 and 2003 b) Texas Department of Criminal Justice - Security Threat Group Officers c) California Department of Corrections d) Sacramento Intelligence Unit LEGEND: BOLD TYPE: Term or Phrase being used (Parenthesis): Used to show the possible origin of the term Meaning: Possible interpretation of the term PLEASE USE EXTREME CARE AND CAUTION IN THE DISPLAY AND USE OF THIS BOOK. DO NOT LEAVE IT WHERE IT CAN BE LOCATED, ACCESSED OR UTILIZED BY ANY UNAUTHORIZED PERSON. Revised: 25 August 2004 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS A: Pages 3-9 O: Pages 100-104 B: Pages 10-22 P: Pages 104-114 C: Pages 22-40 Q: Pages 114-115 D: Pages 40-46 R: Pages 115-122 E: Pages 46-51 S: Pages 122-136 F: Pages 51-58 T: Pages 136-146 G: Pages 58-64 U: Pages 146-148 H: Pages 64-70 V: Pages 148-150 I: Pages 70-73 W: Pages 150-155 J: Pages 73-76 X: Page 155 K: Pages 76-80 Y: Pages 155-156 L: Pages 80-87 Z: Page 157 M: Pages 87-96 #s: Pages 157-168 N: Pages 96-100 COMMENTS: When this “Dictionary” was first started, it was done primarily as an aid for the Security Threat Group Officers in the Texas Department of Criminal Justice (TDCJ). -

Death at the Excelsior

Death At The Excelsior P. G. Wodehouse The Project Gutenberg EBook of Death At The Excelsior, by P. G. Wodehouse Copyright laws are changing all over the world. Be sure to check the copyright laws for your country before downloading or redistributing this or any other Project Gutenberg eBook. This header should be the first thing seen when viewing this Project Gutenberg file. Please do not remove it. Do not change or edit the header without written permission. Please read the "legal small print," and other information about the eBook and Project Gutenberg at the bottom of this file. Included is important information about your specific rights and restrictions in how the file may be used. You can also find out about how to make a donation to Project Gutenberg, and how to get involved. **Welcome To The World of Free Plain Vanilla Electronic Texts** **eBooks Readable By Both Humans and By Computers, Since 1971** *****These eBooks Were Prepared By Thousands of Volunteers!***** Title: Death At The Excelsior Author: P. G. Wodehouse Release Date: May, 2005 [EBook #8176] [This file was first posted on June 26, 2003] Edition: 10 Language: English Character set encoding: US-ASCII *** START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK, DEATH AT THE EXCELSIOR *** eBook prepared by Suzanne L. Shell, Charles Franks, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team DEATH AT THE EXCELSIOR and Other Stories By P. G. Wodehouse [Transcriber's note: This selection of early Wodehouse stories was assembled for Project Gutenberg. The original publication date of each story is listed in square brackets in the Table of Contents.] CONTENTS DEATH AT THE EXCELSIOR [1914] MISUNDERSTOOD [1910] THE BEST SAUCE [1911] JEEVES AND THE CHUMP CYRIL [1918] JEEVES IN THE SPRINGTIME [1921] CONCEALED ART [1915] THE TEST CASE [1915] DEATH AT THE EXCELSIOR I The room was the typical bedroom of the typical boarding-house, furnished, insofar as it could be said to be furnished at all, with a severe simplicity.