A Guide to Responsible Caving

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Junior Cave Scientist Cave and Karst Program Activity Book Ages 5 – 12+

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Geologic Resources Division Junior Cave Scientist Cave and Karst Program Activity Book Ages 5 – 12+ Name: Age: Explore • Learn • Protect 1 Become a Junior Cave Scientist Caves and karst landscapes are found throughout the United States. These features are important as part of our Nation's geologic heritage. In this book, you will explore a fascinating and fragile underground world, learn about the values of caves and karst landscapes, and complete fun educational activities. Explore magnificent and beautiful caves. You will find an amazing underground world just beneath your feet! Learn about caves and karst systems and the work that cave scientists do. Protect our natural environments and the things that make caves and karst areas special. To earn your badge, complete at least activities. (Your Age) Activities in this book are marked with an age indicator. Look for the symbols below: Flashlight Lantern Helmet and Headlamp Ages 5 - 7 Ages 8 – 11 Ages 12 and Older Put a check next to your age indicator on each page that you complete. I received this book from: After completing the activities, there are two ways to receive your Junior Cave Scientist badge: • Return the completed book to a ranger at a participating park, or 2 • Visit go.nps.gov/jrcavesci What are Speleo-Fact: Mammoth Cave is the longest cave in world with over 405 miles (652 km) of connected passageways. Caves and Karst? Caves are naturally occurring voids, cavities, interconnected passageways, or alcoves in the earth. Caves preserve fossils, minerals, ecosystems, and records of past climates. -

SPELUNKING with SOCRATES: a STUDY of SOCRATIC PEDAGOGY in Plato's REPUBLIC

SPELUNKING WITH SOCRATES: A STUDY OF SOCRATIC PEDAGOGY IN PLATo'S REPUBLIC Victor Isaac Boutros Baylor University I. Introduction Though Plato never wrote a dialogue that explicitly asks "Whatis education?" few argue that he is uninterested inthe subject; after all, Plato, like Socrates, was a teacher.l In his magnum opus, theRepublic, Plato deals witheducationrepeat edly. The education of the guardian class and the allegory of the cave present two landmark pedagogical passages. Yet to catch a glimpse of Socratic pedagogy, we must first sift through the intricacies of dialogue. In addition to the com plexity inherent in dramatic context, it seems clear that Socrates' remarks are often steeped inirony.2 Thus, westumble upon a problem: how should we read these passages on education? Does Plato meanfor us to read them genuinelyor ironically? I will argue that Plato uses the dramatic context of the Republic to suggest thatSocrates presents the education of the guardians ironically, while reserving the allegory of the cave for a glimpse of Socrates' genuine pedagogy. The first portion of this paper will analyze various dramatic elements that indicate Socrates' ironic intent with respect to the education of the guardians. The second portion will focus on the alle gory of the cave as Socrates' genuine conception of ideal paideia (or education). II. Dramatic Context and the Introduction of Irony A. Conventional Irony Unfortunately, we cannot look at Plato's treatise on edu cation to learn about his educational theory because he does not write analytical treatises. Instead, Plato employs written dialogues to inspire philosophical insight in his students. -

Caving Humbles the Soul. Underground I Find Myself Doing Things That Are Unimaginable Topside,” Says Mark S

“Caving humbles the soul. Underground I find myself doing things that are unimaginable topside,” says Mark S. Cosslett, adventurer and photographer. 26 163/2003 Mark S. Cosslett Photographer/Adventurer IntoAdventure Canmore, Alberta Canada Reaching Uncharted Caves with the Aid of Accurate Carbon Dioxide Measurement What started as a faint vision nearly five years ago became a reality for our team of three cavers from Canmore, Alberta last January. The karst landscape of Northwest- ern Thailand holds vast treasures of uncharted cave passages, many of which, howev- er, are guarded by high concentrations of carbon dioxide. It was the nemesis of my previous expedition back in ’98 to explore new cave passages: our team invariably got turned around by carbon dioxide. After a lot of research into bad air in caves, we set out to Thailand better equipped this time, carrying lightweight oxygen bottles and a Vaisala CARBOCAP® Hand-Held Carbon Dioxide Meter GM70. arbon dioxide (CO2) is a made us turn back, happy to deadly gas in high con- reach the surface alive. C centrations, which dis- places oxygen and results in rap- If you get into bad air, id asphyxiation. When entering you turn around uncharted passages, high carbon Upon returning home from our dioxide concentrations are one ’98 expedition, all I could think of the risks that cavers face, since about was what was around that an elevated CO2 level can also next corner in the depths of impair one’s judgment. Howev- Thailand. Within 24 hours of er, reliable methods to measure getting off the plane, I was at the CO2 on cave expeditions have library researching carbon diox- been scarce. -

4. Vocabulary Cards Rectificado

n. someone who studies the past by recovering and examining remaining material evidence, such archaeologist as graves, buildings, tools, bones and pottery. “ The archaeologist excavated the site.” n. the study of past human life and culture by the recovery and examination of remaining evidence, such archaeology as graves, buildings, bones and pottery. n. someone who lives in a cave. “Prehistoric man found cave dweller shelter in caves. They became cave dwellers.” n. representations of wild, animals, painted on the walls of caves by prehistoric people, using cave painting simple tools such as fingers, twigs and leaves and using colours found in nature such as brown, red, black and green. adj. relating to the period in human culture before the bronze age, characterised by the chalcolithic use of copper and stone. “The bones were dug up at a chalcolithic site. There were bronze tools there, too.” adj. early form of modern human inhabiting Europe in the late paleolithic period (40,000 – 10,000 years cro-magnon ago). Skeletal remains were first found in the Cro- Magnon cave in southern France. “Homo Sapiens is a cro.magnon man.” n. structure usually regarded as a tomb, dolmen consisting of two or more large upright stones set with a space between and capped by a horizontal stone. n. place where archaeologists dig to find evidence of how excavation site humans lived in the past. “The excavation site is full of interesting things we can use to find out about the past.” n. very hard fine- grained quartz that spark when struck. Prehistoric people used flint this to make tools and start fire. -

The Cradle of Humanity: Prehistoric Art and Culture/ by Georges Bataille : Edited and Introduced by Stum Kendall ; Translated by Michelle Kendall and Stum Kendall

The Cradle of Humanity Prehistoric Art and Culture Georges Bataille Edited and Introduced by Stuart Kendall Translated by Michelle Kendall and Stuart Kendall ZONE BOOKS · NEW YORK 2005 � 2005 UrzoneInc ZONE B001[S 1226 Prospect Avenue Brooklyn, NY 11218 All rights reserved. No pm of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including electronic, mechanical, photocopying, microfihning,recording, or otherwise (except for that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright uw and except by reviewers for the public press) without written permission from the Publisher. Printed in the United States of America. Georges Bataille's writings are O Editions Gallimard, Paris. Distributed by The MIT Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, and London, England Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Bataille, Georges, 1897-1962 The cradle of humanity: prehistoric art and culture/ by Georges Bataille : edited and introduced by Stum Kendall ; translated by Michelle Kendall and Stum Kendall. P· cm. Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 1-890951-55-2 l. Art, prehistoric and science. I. Kendall, Stuart. II. Title. N5310.B382 2004 709'.01 -dc21 Original from Digitized by UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Google Contents Editor's Introduction: The Sediment ofthe Possible 9 A Note on the Translation 33 Primitive Art 35 I The Frobenius Exhibit at the Salle Pleyel 45 II A Visit to Lascaux: A Lecture at the Sociiti d'A9riculture, Sciences, Belles-Lettres III et Arts d'Orlians 47 The Passa9efrom -

Assessing the Short-Term Effect of Minerals Exploration Drilling on Colonies of Bats of Conservation Significance: a Case Study Near Marble Bar, Western Australia

Journal of the Royal Society of Western Australia, 93: 165–174, 2010 Assessing the short-term effect of minerals exploration drilling on colonies of bats of conservation significance: a case study near Marble Bar, Western Australia K N Armstrong Previously: Biota Environmental Sciences Pty Ltd; Currently: Specialised Zoological [email protected]. Manuscript received March 2006; accepted September 2010 Abstract Bats are most vulnerable whilst in their roost, and activities that result in roost destruction or disturbance have the potential to cause declines in species of conservation significance. However, conservation efforts for bat colonies can be limited by a lack of understanding of the effect of certain disturbances. An evaluation drilling programme conducted in close proximity to historical underground gold workings near Marble Bar provided an opportunity to examine the short-term effect of this type of activity on colonies of the bats Macroderma gigas and Rhinonicteris aurantia. A non-invasive approach to assessing the impact of the associated activity was developed, which simultaneously realised the best economy of moving a drill rig. Bats were subject to several types of potential disturbance (from noise and vibration) from earthmoving equipment, the drill rig and the booster compressor. Monitoring involved continuous acoustic and visual observations of mine entrances during drilling, direct counts of emerging bats each evening after drilling, and surveys of other mines in the local area throughout the study. R. aurantia was present throughout the drilling programme, but actual numbers could not be determined accurately. A marked increase in the number of M. gigas was observed, thought to be independent of the activities associated with the drilling programme and possibly due to concurrent human activities in other local mines or natural factors. -

Cave Diving in the Northern Pennines

CAVE DIVING IN THE NORTHERN PENNINES By M.A.MELVIN Reprinted from – The proceedings of the British Speleological Association – No.4. 1966 BRITISH SPELEOLOGICAL ASSOCIATION SETTLE, YORKS. CAVE DIVING IN THE NORTHERN PENNINES By Mick Melvin In this paper I have endeavoured to trace the history and development of cave diving in the Northern Pennines. My prime object has been to convey to the reader a reasonable understanding of the motives of the cave diver and a concise account of the work done in this particular area. It frequently occurs that the exploration of a cave is terminated by reason of the cave passage becoming submerged below water (A sump) and in many cases the sink or resurgence for the water will be found to be some distance away, and in some instances a considerable difference in levels will be present. Fine examples of this occurrence can be found in the Goyden Pot, Nidd Head's drainage system in Nidderdale, and again in the Alum Pot - Turn Dub, drainage in Ribblesdale. It was these postulated cave systems and the success of his dives in Swildons Hole, Somerset, that first brought Graham Balcombe to the large resurgence of Keld Head in Kingsdale in 1944. In a series of dives carried out between August 1944 and June 1945, Balcombe penetrated this rising for a distance of over 200 ft. and during the course of the dive entered at one point a completely waterbound chamber containing some stalactites about 5' long, but with no way on above water level. It is interesting to note that in these early cave dives in Yorkshire the diver carried a 4' probe to which was attached a line reel, a compass, and his lamp which was of the miners' type, and attached to the end of the probe was a tassle of white tape which was intended for use as a current detector. -

National Speleologi'c-Al Society

Bulletin Number Five NATIONAL SPELEOLOGI'C-AL SOCIETY n this Issue: CAVES IN WORLD HISTORY . B ~ BERT MORGAN THE GEM OF CAVES' . .. .. • B DALE WHITE CA VE FAUN A, with Recent Additions to the Lit ture Bl J. A. FOWLER CAT ALOG OF THE SOCIETY LJBR R . B)' ROBERT S. BRAY OCTOBER, 1943 PRJ E 1.0 0 . ------------------------------------------- .-'~ BULLETIN OF THE NATIONAL SPELEOLOGICAL SOCIETY Issue Number Five October, 1943 750 Copies. 64 Pages Published sporadically by THE NATIONAL SPELEOLOGICAL SOCIETY, 510 Scar Building, Washington, D. c., ac $1.00 per copy. Copyrighc, 1943, by THE NATIONAL SPELEOLOGICAL SOCIETY. EDITOR: DON BLOCH 5606 Sonoma Road, Bethesda-14, Maryland ASSOCIATE EDITORS: ROBERT BRAY WILLIAM J. STEPHENSON J. S. PETRIE OFFICERS AND COMMITTEE CHAIRMEN *WM. ]. STEPHENSON J. S. PETR'IE *LEROY FOOTE F. DURR President Vice·Prcsidet1l & Secretary Treasurer Pina~iaJ Sect'eIM"J 7108 Prospect Avenue 400 S. Glebe Road R. D. 3 2005 Kansas Avenue Richmond, Va. Arlin-glon, Va. Waterbury, Conn. Richmond, Va. Archeology Fauna Hydrology Programs &. Activities FLOYD BARLOGA JAMES FOWLER DR. WM. M. MCGILL DR. JAMES BENN 202·8 Lee Boulevard 6420 14th Street 6 Wayside Place, University U. S. Nat. Museum Arlington, Va. Washington, D . C. Charlottesville, Va. Washington, D. C. Bibliography &. Library Finance Mapping PubliCity *ROBERT BRAY *l.EROY FOOTB GBORGE CRABB *·Lou KLBWEJ.t R. F. D. 2 R. F. D. 3 P. O. Box 791 Toledo Blade Herndon, Va. Waterbury, Conn. Blacksburg, Va. Toledo, Ohio BuIletin &. Publications Folklore Metnbership DON BLOCH "'CLAY PERRY SAM ALLBN RECORDS 5606 Sonoma Road East Acres 1226 Wel.Jesley Avenue *FLORENCE WHITLI!Y Deorhesda, Md. -

Caving “Mystery, Adventure, Discovery, Beauty, Conservation, Danger

33104-24.jo_iw_jo 12/11/03 1:28 PM Page 392 33104-24.jo_iw_jo 12/11/03 1:28 PM Page 393 24 Caving “Mystery, adventure, discovery, beauty, conservation, danger. To many who are avid cavers and speleologists, caves are all of these things and many more, too.” —David R. McClurg (caver, subterranean photographer, caving skills instructor, and longtime member of the National Speleological Society), The Amateur’s Guide to Caves and Caving, 1973 Beneath the Earth’s surface lies a magnificent realm darker than a moonless night. No rain falls. No storms rage. The seasons never change. Other than the ripple of hidden streams and the occasional splash of dripping water, this underground world is silent, yet it is not without life. Bats fly with sure reckoning through mazes of tunnels, and eyeless creatures scurry about. Transparent fish stir the waters of underground streams, and the darkness is home to tiny organisms seldom seen in broad daylight. This is the world of the cave, as beautiful, alien, and remote as the glaciated crests of lofty mountains. Just as climbers are tempted by summits that rise far above familiar ground, cavers are drawn into a subterranean wilderness every bit as exciting and remarkable as any place warmed by the rays of the sun. Water is the most common force involved in the creation of caves. As it seeps through the earth, moisture can dissolve limestone, gypsum, and other sedimentary rock. Surf pounding rocky cliffs can, over the centuries, carve out sea caves of spectacular shape and dimension. The surface of lava flowing from a volcanic eruption can cool and harden while molten rock runs out below it, leaving behind lava tubes. -

Cave Bats in Jamaica Donald A

Cave bats in Jamaica Donald A. McFarlane Jamaica has 22 native mammal species. One may cause serious disturbance to the colonies. of these is an endangered rodent, the Wallingford Cave, in St Elizabeth Parish, is a large Jamaican hutia Geocapromys browni; the rest but short blind tunnel close to a road that was for a are all bats. Fifteen of these bats depend time mined for its guano deposits (Peck, 1975). entirely or significantly on caves as roost sites, By August 1977 the bat colony had disappeared, including two endemic species and seven and it seems possible that excessive disturbance endemic subspecies. These cave-dwelling bats may have been responsible. often form large colonies whose guano deposits are of significant economic value as An examination of the literature suggests that 15 fertilizer, but which are vulnerable to disturb- of Jamaica's bats are significantly or entirely ance and roost destruction. The author, who dependent on caves as day roosts (Table 1). Six has visited and worked in many of Jamaica's of these species are of special concern and are bat caves over the past eight years, is currently discussed below. Taxonomy and vernacular researching the evolution and development of names follow Hall (1982). the Antillean bat faunas. The Jamaican flower bat Of Jamaica's 950 documented caves (Fincham, Phyllonycteris aphylla 1977), approximately 17 per cent are known to host bat colonies of sizes varying from a few This bat is endemic to Jamaica and is known from dozen to tens of thousands of individuals. The only three caves: St Clair Cave, Riverhead Cave, cave-dwelling bats of Jamaica are not evenly dis- and Mt Plenty Cave (Goodwin, 1970). -

Project Nature Newsletter-February 2019

PROJECT NATURE NEWSLETTER PROJECT NATURE NEWSLETTER FEBRUARY, 2019 ISSUE E U S S I 9 1 0 2 Y R A U R B E F PROJECT NATURE NEWSLETTER Events 46th Annual Winter Hike Series Great Backyard Bird Count Highbanks Metro Park - Northern Shelter Blacklick Woods Metro Park - Nature Center 9th February 10:00 am - 12:00 pm 16th Feb 10:00 am-11:00 am, 17th Feb 2:00-3:00 PM Join us for the annual winter hike with options for 2.5 Watch the feeders and count birds to participate in the or 5 miles. Refreshments afterward Great Backyard Bird Count Winter Tree ID: Silhouettes and Branches EPN Breakfast - Justice, Equity, Diversity, Inclusion Inniswood Gardens Metro Park - Gardens Entrance Nationwide and Ohio Farm Bureau 4-H Center 9th February 2:00 pm - 3:00 pm 2201 Fred Taylor Dr Learn how to identify our local trees focusing on 12th February 7:15 am - 9:30 am characteristics of tree form Join the conversation about diversity and inclusion in environmental NGOs, while enjoying breakfast hosted by the Environment Professionals Network Owls of February Registration - Free for students ($10 otherwise) Three Creeks Metro Park - Confluence Area 9th February 6:00 pm - 7:00 pm Winter Bird Hike Learn about Ohio's owls as we walk through the Blendon Woods Metro Park - Nature Center woods and try to lure them with calls 16th February 9:00 am - 10:00 am Visit Thoreau Lake and view our wintering waterfowl Weekly Bird Hike Scioto Audobon Metro Park - Grange Insurance Ice Age Ohio Audobon Center Battelle Darby Creek Metro Park - Indian Ridge 9th, 16th, 23rd Feb, 2nd -

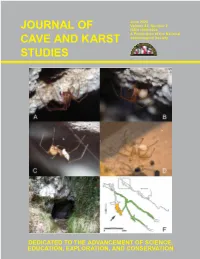

Journal of Cave and Karst Studies

June 2020 Volume 82, Number 2 JOURNAL OF ISSN 1090-6924 A Publication of the National CAVE AND KARST Speleological Society STUDIES DEDICATED TO THE ADVANCEMENT OF SCIENCE, EDUCATION, EXPLORATION, AND CONSERVATION Published By BOARD OF EDITORS The National Speleological Society Anthropology George Crothers http://caves.org/pub/journal University of Kentucky Lexington, KY Office [email protected] 6001 Pulaski Pike NW Huntsville, AL 35810 USA Conservation-Life Sciences Julian J. Lewis & Salisa L. Lewis Tel:256-852-1300 Lewis & Associates, LLC. [email protected] Borden, IN [email protected] Editor-in-Chief Earth Sciences Benjamin Schwartz Malcolm S. Field Texas State University National Center of Environmental San Marcos, TX Assessment (8623P) [email protected] Office of Research and Development U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Leslie A. North 1200 Pennsylvania Avenue NW Western Kentucky University Bowling Green, KY Washington, DC 20460-0001 [email protected] 703-347-8601 Voice 703-347-8692 Fax [email protected] Mario Parise University Aldo Moro Production Editor Bari, Italy [email protected] Scott A. Engel Knoxville, TN Carol Wicks 225-281-3914 Louisiana State University [email protected] Baton Rouge, LA [email protected] Exploration Paul Burger National Park Service Eagle River, Alaska [email protected] Microbiology Kathleen H. Lavoie State University of New York Plattsburgh, NY [email protected] Paleontology Greg McDonald National Park Service Fort Collins, CO The Journal of Cave and Karst Studies , ISSN 1090-6924, CPM [email protected] Number #40065056, is a multi-disciplinary, refereed journal pub- lished four times a year by the National Speleological Society.