Woody Guthrie's ''Tom Joad''

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Samoan Submission Machines

Samoan Submission Machines: Grappling with Representations of Samoan Identity in Professional Wrestling Theo Plothe1 Savannah State University [email protected] Amongst the myriad of characters to step foot in the squared circle, perhaps no ethnic group has been as celebrated or marginalized as the Samoans who have made their names in professional wrestling. The discussion of Samoan identity in the context of sport has examined Maori identity and masculinity in New Zealand, among other topics, but there has yet to be work which considers Samoans within professional wrestling. This research investigates Samoan identity through a content analysis of televised wrestling matches. This research identifies six primary stereotypes under which Samoan identity is portrayed. These portrayals of Samoan characters, I argue, flatten the representation of this ethnic group within wrestling and culture at large. Keywords: Samoans, identity, representation, gimmicks Introduction Among the myriad of characters to step foot in the squared circle, perhaps no ethnic group has been as celebrated or marginalized as the Samoans who have made their names in professional wrestling. This research investigates the identity of Samoans within professional wrestling, and the different ways they are constructed and presented to audiences. “Gimmicks,” characters portrayed by a wrestler “resulting in the sum of fictional elements, attire and wrestling ability” (Oliva and Calleja 3) utilized by Samoans have run the gamut from the wild uncivilized savage, to the sumo (both in villainous Japanese and comically absurd iterations), to the ultra-cool mogul who wears silk shirts and fancy shoes. Their ability to cut promos, an important facet of the modern gimmick allowing wrestlers to address their opponents and storylines, varies widely as well, but all lie within their Samoan identity. -

More About the Album Thank Yous • About the Guitars

Produced by AM & Dustin DeLage Recording, engineering and mixing by Dustin DeLage at Cabin Studios, Leesburg VA Additional remote recording by Ken Lubinsky at lack Hills Studios, Plain"eld CT Atlantic $cean wa&es recorded by Mic'elle McKnig't at East eac', Charlestown R)* Mastering by ill +ol,, +ol, Productions, Alexandria VA* -ra.'ic Design by Stilson -reene, Leesburg VA ack co&er .'oto by Christi Porter P'otogra.'y, Lincoln VA All songs written by AM and ©Catalooch Music, BMI, except "Margaret" by Andrew McKnight ©19 !, "uccess Music, and "#ur Meeting Is #ver" %traditional&' #'e Songs #'e and 1. Embarking 1:12 ,M - vo<a-s7 a<ousti< & e-e<tri< guitars7 s-i"e guitar7 2. Margaret/Treasures in My Chest 4:56 &ative Ameri<an fute 3. Web of Mystery 3:24 9a<he- Tay-or - ce--o 4. eft Behin" 3:55 Mi<hae- Rohrer ; e-e<tri< an" u:right bass 5. #assage/(Fathers No') Our Meeting is Over 2:1+ isa Tay-or - drums7 harmony vo<a-s 6. ,retas Cu-ver 4:13 >ef Arey - man"o-in .. , Dram to the Ho-i"ays 5:13 4te:hanie Thom:son7 Tony Denikos - harmony vo<a-s 1. The Gift 3:51 3. 4ons & Fathers 3:53 $t'er Essential Musical Pieces 1+. My Litt-e To'n 3:35 ,-y M<@night - piano (Margaret( 11. ong Ago an" Far A'ay 1:5+ Warren M<@night - piano an" organ $4ons & Fathers( 12. Entre-azan"o 0:43 Ma"e-eine M<@night - f""-e (Long Ago & Far A'ay(7 13. -

Dust Bowl Balladeer Next Door Who Would Have Thought That the Dust Bowl Balladeer Texas; Jobs Such As Working in the Men

Vol. 9, Issue 1 Dr. Jeanne Ramirez Mather, Ed. December 2006 The Genius Kid Dust Bowl Balladeer Next Door Who would have thought that The Dust Bowl Balladeer Texas; jobs such as working in the men. In 1939 he moved to David Meigooni at age 14 would was Okemah native Woody fields, carpentry, moving garbage New York and wrote and be an award winning scientist? Guthrie, who was named after cans, shining shoes, painting signs, worked with such folk singers Of course he started before he Woodrow Wilson. While and washing spittoons. His life as Burl Ives and Pete Seeger. In was 14. In fourth grade he de- Woody is often referred to as changed when his uncle bought 1940 he wrote the song perhaps veloped a science project called the voice of the common man him a guitar and taught him to he is best known for, This Land “Mom’s Fear of Radiation” in and a singer with a social con- play. He found that all around him is Your Land. The Department which he proved that his mother science, he was also a Renais- was life worth singing about. He of Interior commissioned actually was exposed to more sance Man. He was not only a wrote about what he saw and Woody in 1941 to write songs radiation while gardening than singer, musician, and song felt—the good, the bad, and how about the Grand Coulee Dam while watching television. writer, but also an artist and an to make things right. being built in Oregon. This in- Later he wondered if the rela- author. -

Ruination Day”

Woody Guthrie Annual, 4 (2018): Fernandez, “Ruination Day” “Ruination Day”: Gillian Welch, Woody Guthrie, and Disaster Balladry1 Mark F. Fernandez Disasters make great art. In Gillian Welch’s brilliant song cycle, “April the 14th (Part 1)” and “Ruination Day,” the Americana songwriter weaves together three historical disasters with the “tragedy” of a poorly attended punk rock concert. The assassination of Abraham Lincoln in 1865, the sinking of the Titanic in 1912, and the epic dust storm that took place on what Americans call “Black Sunday” in 1935 all serve as a backdrop to Welch’s ballad, which also revolves around the real scene of a failed punk show that she and musical partner David Rawlings had encountered on one of their earlier tours. The historical disasters in question all coincidentally occurred on the fourteenth day of April. Perhaps even more important, the history of Welch’s “Ruination Day” reveals the important relationship between history and art as well as the enduring relevance of Woody Guthrie’s influence on American songwriting.2 Welch’s ouevre, like Guthrie’s, often nods to history. From the very instruments that she and Rawlings play to the themes in her original songs to the tunes she covers, she displays a keen awareness and reverence for the past. The sonic quality of her recordings, along with her singing and musical style, also echo the past. This historical quality is quite deliberate. Welch and Rawlings play vintage instruments to achieve much of that sound. Welch’s axes are all antiques—her main guitar is a 1956 Gibson J-50. -

The Woody Guthrie Centennial Bibliography

LMU Librarian Publications & Presentations William H. Hannon Library 8-2014 The Woody Guthrie Centennial Bibliography Jeffrey Gatten Loyola Marymount University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/librarian_pubs Part of the Music Commons Repository Citation Gatten, Jeffrey, "The Woody Guthrie Centennial Bibliography" (2014). LMU Librarian Publications & Presentations. 91. https://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/librarian_pubs/91 This Article - On Campus Only is brought to you for free and open access by the William H. Hannon Library at Digital Commons @ Loyola Marymount University and Loyola Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in LMU Librarian Publications & Presentations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Loyola Marymount University and Loyola Law School. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Popular Music and Society, 2014 Vol. 37, No. 4, 464–475, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/03007766.2013.834749 The Woody Guthrie Centennial Bibliography Jeffrey N. Gatten This bibliography updates two extensive works designed to include comprehensively all significant works by and about Woody Guthrie. Richard A. Reuss published A Woody Guthrie Bibliography, 1912–1967 in 1968 and Jeffrey N. Gatten’s article “Woody Guthrie: A Bibliographic Update, 1968–1986” appeared in 1988. With this current article, researchers need only utilize these three bibliographies to identify all English- language items of relevance related to, or written by, Guthrie. Introduction Woodrow Wilson Guthrie (1912–67) was a singer, musician, composer, author, artist, radio personality, columnist, activist, and philosopher. By now, most anyone with interest knows the shorthand version of his biography: refugee from the Oklahoma dust bowl, California radio show performer, New York City socialist, musical documentarian of the Northwest, merchant marine, and finally decline and death from Huntington’s chorea. -

Resb.F:E:Ii9~Ncjl AGEND/\ to BE POSTED #S1f Woody Guthrie Day- --·- ~~~

.' _'';"'~·.•>'.;,_(.f_~""'-n.~~.-- .......,.,., ........... ~ _,,I · I ·~? pny CLtrxr< FOR P=-:-L-/{C_E_M_Er·~-r~o-N_N_o_o_·-r---.... REsb.f:e:ii9~NCJl AGEND/\ TO BE POSTED #S1f Woody Guthrie Day- --·- ~~~ .... -':...~~~ April12, 2012 WHEREAS, Woody Guthrie is a renowned singer-songwriter who stands as one of America's most important folk music artists of the first half of the 20th Century; and WHEREAS, Woody Guthrie stood out for his songwriting abilities and will best be remembered for his seminal folk music piece "This Land if Your Land" amongst many other hits like "Deportee," "Do Re Mi,'' ,.Grand Coulee Dam/' "Hard, Ain't It Hard,'' "Hard Travelin'," "I Ain't Got No Home," "1913 Massacre,'1 11 0klahoma Hills,~~ "Pastures ofPlenty,rr "Philadelphia Lawyer,'1 "Pretty Boy Floyd," 11 Ramblin1 Round," "So Long It'sBeen Good to Know You,t' "Talking Dust Bowl, '1 and 11 Vigilante Man" that have been covered by other artists throughout the century; and WHEREAS, Woodrow Wilson Guthrie was born in Okemah, Oklahoma learning folk songs from his mother as a child; and WHEREAS, in 1940, assembling works that were based on his experience as an "Okie" during the Dust Bowl era, in which many migrant workers suffered tremendous economic hardship on their way to California, he released the "Dust Bowl Ballads" that are renowned for their dramatic retelling of Great Depression era plight; and .i WHEREAS, A century after his birth in July of 1912, Woody Guthrie has acquired an iconic stature in American popular culture and music. Guthrie was known in the as a folksinger who in the 1930s and 1940s gave a voice to the working class, the mentor and musical image to Bob Dylan and other singer-songwriters in the 1950s and 1960s, and the author of great American songs like "This Land is Your Land." WHEREAS, In 193 7, when many dust bowl refugees were making a new life in California, Woody Guthrie lived in Los Angeles. -

Steinbeck, Guthrie and Zanuck: a Dust Bowl Triptych. the Intertextual Life of the Grapes of Wrath on Paper, Celluloid and Vinyl”, Crossroads

Foulds, Peter. “Steinbeck, Guthrie and Zanuck: a Dust Bowl Triptych. The Intertextual Life of The Grapes of Wrath on Paper, Celluloid and Vinyl”, Crossroads. A Journal of English Studies 4 (1/2014), 50-58. Peter Foulds The University of Bialystok Steinbeck, Guthrie and Zanuck: a Dust Bowl Triptych. The Intertextual Life of The Grapes of Wrath on Paper, Celluloid and Vinyl Abstract. In a world where the arts have become one more target for multimedia corporations it is worth remembering the more authentic intertextuality of works which appeared around 1940, i.e. John Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath, Darryl F. Zanuck and John Ford’s film of the same name, and the songs of Woody Guthrie. Never before had literature, cinema and song been so intimately and powerfully linked, and nothing since has come near to replicating this unique symbiosis. Keywords: Dust Bowl, Great Depression, intertextuality. Along with blatant product placement in films Hollywood accountants today build into their projects spin-offs and tie-ins, such as board games, school accessories, books of the film, clothing, and anything else that can capture the imaginations and money of the audience. In a less cynical age the process was more organic. John Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath (published 75 years ago this April) inspired Darryl F. Zanuck and John Ford to make their great film of the same name, and Woody Guthrie to write songs celebrating its characters. As the journalist Alan Yuhas recently pointed out, “[Steinbeck] inspired Cesar Chavez and John Kennedy; Bruce Springsteen and Woody Guthrie (and by extension Rage Against the Machine); John Ford and South Park.” Yunas goes on to say that The Grapes of Wrath “means just as much to the US now as it did in 1939, when the Dust Bowl destroyed the American west, the economy lay in tatters, a minority held the keys to the bank, and a vast migrant population wandered without homes or rights.” (www.theguardian.com.). -

Everybody's Got a Hungry Heart

Everybody’s Got a hungry heart The Duality in Bruce Springsteen by Andy Paine Two hearts This zine is the result of years of trying to explain to various people my love of Bruce Springsteen and the E Street Band. For many, especially those like me who were born after Bruce’s commercial peak with Born In The USA, Bruce Springsteen is like peak hour traffic or the internet or something – so ubiquitous in our subconscious that you never really think about it. On classic hits radio, in karaoke bars, as a trope to be imitated and parodied; his epic songs of cadillacs and highways and American dreams can be seen as just another kitschy relic of another time, or just one more attack in the never-ending onslaught of US pop culture imperialism. I think that’s why some people are surprised to discover my great love of Bruce Springsteen. But love him I do, and my feelings have only grown stronger the older I have gotten. Partial as I am to a good classic rock song or sax solo; it’s Springsteen the lyricist that I love. So many of his songs are little short stories, and these vignettes avoid tales of rockstar excess or high-concept artistic statement. They are stories of ordinary working class people, written in the classic language of ordinary working class people – rock’n’roll. In this way there is certainly a simplicity to Bruce Springsteen. And I’m sure for many listeners, “The Boss” represents a nostalgic ideal of a simpler, rose-tinted Americana. -

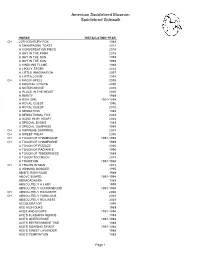

Saddlebred Sidewalk List 1989-2018

American Saddlebred Museum Saddlebred Sidewalk HORSE INSTALLATION YEAR CH 20TH CENTURY FOX 1989 A CHAMPAGNE TOAST 2011 A CONVERSATION PIECE 2014 A DAY IN THE PARK 2018 A DAY IN THE SUN 1999 A DAY IN THE SUN 1998 A KINDLING FLAME 1989 A LIKELY STORY 2014 A LITTLE IMAGINATION 2007 A LOTTA LOVIN' 1998 CH A MAGIC SPELL 2005 A MAGICAL CHOICE 2000 A NOTCH ABOVE 2016 A PLACE IN THE HEART 2000 A RARITY 1989 A RICH GIRL 1991-1994 A ROYAL QUEST 1996 A ROYAL QUEST 2010 A SENSATION 1989 A SENSATIONAL FOX 2002 A SONG IN MY HEART 2004 A SPECIAL EVENT 1989 A SPECIAL SURPRISE 1998 CH A SUPREME SURPRISE 2001 CH A SWEET TREAT 2000 CH A TOUCH OF CHAMPAGNE 1991-1994 CH A TOUCH OF CHAMPAGNE 1989 A TOUCH OF PIZZAZZ 2006 A TOUCH OF RADIANCE 1995 A TOUCH OF TENDERNESS 1989 A TOUCH TOO MUCH 2018 A TRADITION 1991-1994 CH A TRAVELIN' MAN 2012 A WINNING WONDER 1995 ABIE'S IRISH ROSE 1989 ABOVE BOARD 1991-1994 ABRACADABRA 1989 ABSOLUTELY A LADY 1999 ABSOLUTELY COURAGEOUS 1991-1994 CH ABSOLUTELY EXQUISITE 2005 CH ABSOLUTELY FABULOUS 2001 ABSOLUTELY NO LIMITS 2001 ACCELERATOR 1998 ACE HIGH DUKE 1989 ACES AND EIGHTS 1991-1994 ACE'S FLASHING GENIUS 1989 ACE'S QUEEN ROSE 1991-1994 ACE'S REFRESHMENT TIME 1989 ACE'S SOARING SPIRIIT 1991-1994 ACE'S SWEET LAVENDER 1989 ACE'S TEMPTATION 1989 Page 1 American Saddlebred Museum Saddlebred Sidewalk HORSE INSTALLATION YEAR ACTIVE SERVICE 1996 ADF STRICTLY CLASS 1989 ADMIRAL FOX 1996 ADMIRAL'S AVENGER 1991-1994 ADMIRAL'S BLACK FEATHER 1991-1994 ADMIRAL'S COMMAND 1989 CH ADMIRAL'S FLEET 1998 CH ADMIRAL'S MARK 1989 CH ADMIRAL'S MARK -

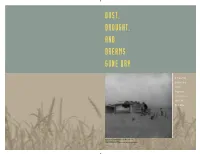

Dust, Drought, and Dreams Gone Dry

DUST, DROUGHT, AND DREAMS GONE DRY A Traveling Exhibit and Public Programs for Libraries about the Dust Bowl Farmer and sons walking in the face of a dust storm, 1936 Arthur Rothstein, photographer Courtesy of the Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Resources Related Readings: Please visit ala.org/ Sanora Babb. Whose Names Are Unknown. University of programming/dustbowl Oklahoma Press, 1979. for a complete list of Geoff Cunfer. On the Great Plains: Agriculture and Environment. library host sites. Texas A&M University Press, 2005. Timothy Egan. The Worst Hard Time. Houghton Mifflin, 2006. Caroline Henderson. Edited by Alvin O. Turner. Letters From the Dust Bowl. University of Oklahoma Press, 2001. R. Douglas Hurt. The Dust Bowl: An Agricultural and Social Any views, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this exhibition History. Nelson-Hall, 1981. do not necessarily represent those of the Bison herd at water, circa 1905 National Endowment for the Humanities. Courtesy of the Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Pamela Riney-Kehrberg. Rooted in Dust: Surviving Drought and Depression in Southwestern Kansas. University Press of Kansas, 1994. The Geography and People of the Plains John Steinbeck. The Grapes of Wrath. Viking Press, 1939. Donald Worster. Dust Bowl: The Southern Plains in the 1930s. Living on the Plains depended on rainfall, but many people Oxford University Press, 1979. and animals thrived there. Bison shared the Plains with other Music: animals and with different groups of indigenous people for Woody Guthrie. Dust Bowl Ballads. RCA Victor, 1940. thousands of years. Comanche, Cheyenne, Kiowa, and others On the Web: called the Southern Plains home. -

Woody Guthrie

120742bk Woody 10/6/04 3:59 PM Page 2 1. Talking Dust Bowl Blues 2:43 9. Jesus Christ 2:45 16. This Land Is Your Land 2:17 19. Talking Columbia Blues 2:37 (Woody Guthrie) (Woody Guthrie) (Woody Guthrie) (Woody Guthrie) Victor 26619, mx BS 050146-2 Asch 347-3, mx MA 135 Folkways FP 27 Disc 5012, mx D 202 Recorded 26 April 1940 Recorded c. April 1944 Recorded c. 1945 Recorded c. April 1947 2. Blowin’ Down This Road 3:05 10. New York Town 2:40 17. Pastures Of Plenty 2:31 Woody Guthrie, vocal and guitar (Woody Guthrie–Lee Hays) (Woody Guthrie) (Woody Guthrie) All selections recorded in New York Victor 26619, mx BS 050150-1 With Cisco Houston Disc 5010, mx D 199 Recorded 26 April 1940 Asch 347-3, mx MA 21 Recorded c. April 1947 Transfers & Production: David Lennick 3. Do Re Mi 2:38 Recorded 19 April 1944 18. Ramblin’ Blues 2:19 Digital Noise Reduction by K&A Productions Ltd (Woody Guthrie) 11. Who’s Gonna Shoe Your Pretty Little (Woody Guthrie) Original recordings from the collections of David Victor 26620, mx BS 050153-1 Feet 2:35 Disc 5011, mx D 201 Lennick & John Rutherford Recorded 26 April 1940 (Traditional) Recorded c. April 1947 4. Tom Joad 6:31 With Cisco Houston Asch 432-4, mx MA 27 Original monochrome photo of Woody Guthrie from Rue des Archives/Lebrecht Music & Arts; (Woody Guthrie) background from Corbis Images. Victor 26621, mx BS 050159-1, 050152-1 Recorded 19 April 1944 Recorded 26 April 1940 12. -

Woody Guthrie and the Writing of “Balladsongs” � �Mark F

ISSN 2053-8804 Woody Guthrie Annual, 3 (2017): Fernandez: Guthrie and the Writing of “Balladsongs” “The Only Way That I Could Cry”: Woody Guthrie and the Writing of “Balladsongs” ! !Mark F. Fernandez Woody Guthrie wrote about everything. He even coined a motto about it at the end of his most famous lyric sheet: “All you can write is what you see.”1 And he saw just about everything there was to see of the mid-twentieth-century American experience. His famous travels took him throughout most of the then forty-eight states, and like so many Americans of his day, World War II acquainted him with life on the high seas, the coasts of Africa, and parts of Europe. As he wrote about the things he saw and the causes he came to embrace, Guthrie developed an approach to the songwriting process that he shared with anyone who would listen and even some that probably did not want his advice at all. That approach has gone on to influence generations of songwriters ever since — their legion is often dubbed “Woody’s Children.” Peers like Pete Seeger, Lee Hays, Ronnie Gilbert, and Fred Hellerman, who would go on to form the influential folk/pop group The Weavers, recorded Woody’s songs, emulated his songwriting process in their own work, and helped spark a “folk revival” that energized the 1950s and 60s. Young entertainers like Ramblin’ Jack Elliot and Bob Dylan sought out and copied Guthrie as they developed their own craft. More recently, artists like Billy Bragg, Jay Farrar, and Jonatha Brooke have counted Guthrie as a major influence and have even adapted his unpublished lyrics in some of their recordings as well as incorporating his “all you can write is what you see” mentality into their own creative processes.