Outline Plan of Scoping Project for the Environmental Issues Overview

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Geology of the Wairarapa Area

GEOLOGY OF THE WAIRARAPA AREA J. M. LEE J.G.BEGG (COMPILERS) New International NewZOaland Age International New Zealand 248 (Ma) .............. 8~:~~~~~~~~ 16 il~ M.- L. Pleistocene !~ Castlecliffian We £§ Sellnuntian .~ Ozhulflanl Makarewan YOm 1.8 100 Wuehlaplngien i ~ Gelaslan Cl Nukumaruan Wn ~ ;g '"~ l!! ~~ Mangapanlan Ql -' TatarianiMidian Ql Piacenzlan ~ ~;: ~ u Wai i ian 200 Ian w 3.6 ,g~ J: Kazanlan a.~ Zanetaan Opoitian Wo c:: 300 '"E Braxtonisn .!!! .~ YAb 256 5.3 E Kunaurian Messinian Kapitean Tk Ql ~ Mangapirian YAm 400 a. Arlinskian :;; ~ l!!'" 500 Sakmarian ~ Tortonisn ,!!! Tongaporutuan Tt w'" pre-Telfordian Ypt ~ Asselian 600 '" 290 11.2 ~ 700 'lii Serravallian Waiauan 5w Ql ." i'l () c:: ~ 600 J!l - fl~ '§ ~ 0'" 0 0 ~~ !II Lillburnian 51 N 900 Langhian 0 ~ Clifdenian 5e 16.4 ca '1000 1 323 !II Z'E e'" W~ A1tonian PI oS! ~ Burdigalian i '2 F () 0- w'" '" Dtaian Po ~ OS Waitakian Lw U 23.8 UI nlan ~S § "t: ." Duntroonian Ld '" Chattian ~ W'" 28.5 P .Sll~ -''" Whalngaroan Lwh O~ Rupelian 33.7 Late Priabonian ." AC 37.0 n n 0 I ~~ ~ Bortonian Ab g; Lutetisn Paranaen Do W Heretauncan Oh 49.0 354 ~ Mangaorapan Om i Ypreslan .;;: w WalD8wsn Ow ~ JU 54.8 ~ Thanetlan § 370 t-- §~ 0'" ~ Selandian laurien Dt ." 61.0 ;g JM ~"t: c:::::;; a.os'"w Danian 391 () os t-- 65.0 '2 Maastrichtian 0 - Emslsn Jzl 0 a; -m Haumurian Mh :::;; N 0 t-- Campanian ~ Santonian 0 Pragian Jpr ~ Piripauan Mp W w'" -' t-- Coniacian 1ij Teratan Rt ...J Lochovlan Jlo Turonian Mannaotanean Rm <C !II j Arowhanan Ra 417 0- Cenomanian '" Ngaterian Cn Prldoli -

The 1934 Pahiatua Earthquake Sequence: Analysis of Observational and Instrumental Data

221 THE 1934 PAHIATUA EARTHQUAKE SEQUENCE: ANALYSIS OF OBSERVATIONAL AND INSTRUMENTAL DATA Gaye Downes1' 2, David Dowrick1' 4, Euan Smith3' 4 and Kelvin Berryman1' 2 ABSTRACT Descriptive accounts and analysis of local seismograms establish that the epicentre of the 1934 March 5 M,7.6 earthquake, known as the Pahiatua earthquake, was nearer to Pongaroa than to Pahiatua. Conspicuous and severe damage (MM8) in the business centre of Pahiatua in the northern Wairarapa led early seismologists to name the earthquake after the town, but it has now been found that the highest intensities (MM9) occurred about 40 km to the east and southeast of Pahiatua, between Pongaroa and Bideford. Uncertainties in the location of the epicentre that have existed for sixty years are now resolved with the epicentre determined in this study lying midway between those calculated in the 1930' s by Hayes and Bullen. Damage and intensity summaries and a new isoseismal map, derived from extensive newspaper reports and from 1934 Dominion Observatory "felt reports", replace previous descriptions and isoseismal maps. A stable solution for the epicentre of the mainshock has been obtained by analysing phase arrivals read from surviving seismograms of the rather small and poorly equipped 1934 New Zealand network of twelve stations (two privately owned). The addition of some teleseismic P arrivals to this solution shifts the location of the epicentre by less than 10 km. It lies within, and to the northern end of, the MM9 isoseismal zone. Using local instrumental data larger aftershocks and other moderate magnitude earthquakes that occurred within 10 days and 50 km of the mainshock have also been located. -

Fishing-Regs-NI-2016-17-Proof-D.Pdf

1 DAY 3 DAY 9 DAY WINTER SEASON LOCAL SENIOR FAMILY VISITOR Buy your licence online or at stores nationwide. Visit fishandgame.org.nz for all the details. fishandgame.org.nz Fish & Game 1 DAY 3 DAY 9 DAY WINTER SEASON LOCAL SENIOR 1 FAMILY 2 VISITOR 3 5 4 6 Check www.fishandgame.org.nz for details of regional boundaries Code of Conduct ....................................................................... 4 National Sports Fishing Regulations ..................................... 5 Buy your licence online or at stores nationwide. First Schedule ............................................................................ 7 Visit fishandgame.org.nz 1. Northland ............................................................................ 11 for all the details. 2. Auckland/Waikato ............................................................ 14 3. Eastern .................................................................................. 20 4. Hawke's Bay .........................................................................28 5. Taranaki ............................................................................... 32 6. Wellington ........................................................................... 36 The regulations printed in this guide booklet are subject to the Minister of Conservation’s approval. A copy of the published Anglers’ Notice in the New Zealand Gazette is available on www.fishandgame.org.nz Cover Photo: Nick King fishandgame.org.nz 3 Regulations CODE OF CONDUCT Please consider the rights of others and observe the -

Agenda of Environment Committee

I hereby give notice that an ordinary meeting of the Environment Committee will be held on: Date: Tuesday, 14 May 2019 Time: to follow the Strategy & Policy Committee meeting Venue: Tararua Room Horizons Regional Council 11-15 Victoria Avenue, Palmerston North ENVIRONMENT COMMITTEE AGENDA MEMBERSHIP Chair Cr GM McKellar Deputy Chair Cr WK Te Awe Awe Councillors Cr JJ Barrow Cr LR Burnell Cr DB Cotton Cr EB Gordon JP (ex officio) Cr RJ Keedwell Cr NJ Patrick Cr JM Naylor Cr PW Rieger, QSO JP Cr BE Rollinson Cr CI Sheldon Michael McCartney Chief Executive Contact Telephone: 0508 800 800 Email: [email protected] Postal Address: Private Bag 11025, Palmerston North 4442 Full Agendas are available on Horizons Regional Council website www.horizons.govt.nz Note: The reports contained within this agenda are for consideration and should not be construed as Council policy unless and until adopted. Items in the agenda may be subject to amendment or withdrawal at the meeting. for further information regarding this agenda, please contact: Julie Kennedy, 06 9522 800 CONTACTS 24 hr Freephone : [email protected] www.horizons.govt.nz 0508 800 800 SERVICE Kairanga Marton Taumarunui Woodville CENTRES Cnr Rongotea & 19-21 Hammond 34 Maata Street Cnr Vogel (SH2) & Tay Kairanga-Bunnythorpe Rds, Street Sts Palmerston North REGIONAL Palmerston North Whanganui HOUSES 11-15 Victoria Avenue 181 Guyton Street DEPOTS Levin Taihape 120-122 Hokio Beach Rd 243 Wairanu Rd POSTAL Horizons Regional Council, Private Bag 11025, Manawatu Mail Centre, Palmerston North -

THE NEW ZEALAND GAZETTE No

1050 THE NEW ZEALAND GAZETTE No. 37 Amount Date Persons Believed to be Entitled Held Received $ Shaw, J., Featherston 2.40 20/9/68 Shaw, T., Greytown .. 24.00 20/9/68 Sheath, A., Masterton 12.00 20/9/68 Sheehyn, M. J., Eketahuna 4.80 29/9/68 Shekleton, A. B., Pahiatua 12.00 20/9/68 Sheppard, W. S., Mangatainoka 2.40 20/9/68 Shirkey, J., French Street, Martinborough 2.40 20/9/68 Shirkey, J., Martinborough 4.80 20/9/68 Shirtciiffe, W. S., Mangatainoka 2.40 20/9/68 Short, G., 175 The Terrace, Wellington .. 2.40 20/9/68 Sibbald, L. S. T., Owendale, Saunders Road, Eketahuna 2.40 20/9/68 Siemonex, E., High Street, Masterton 2.40 20/9/68 Signertsen, J. P., Rongokokako 2.40 20/9/68 Simmers, E. M., Eketahuna 4.80 20/9/68 Simmonds, H., Parkville 2.40 20/9/68 Simmonds, W. D., Ashby's Line, South Featherston 2.40 20/9/68 Simms, F. R., 40 Raroa Road, Kelburn, Wellington 2.40 20/9/68 Simpson, W., Eketahuna 4.80 20/9/68 Sisson, J., Matamau 4.80 20/9/68 Skerman, J. A. (executors), care of A. A. Podeviw, Te Kuiti 40.00 20/9/68 Skipwith, R. H., Melwood, Dannevirke 4.80 20/9/68 Slacke, R. H., Mangamutu, Pahiatua 2.40 20/9/68 Sladden, H., Woburn Road, Lower Hutt 2.40 20/9/68 Small, C. F., Penrose, Masterton 2.40 20/9/68 Small, R. M., Eketahuna 2.40 20/9/68 Small, W. -

BEFORE the HEARING PANEL in the MATTER of the Resource Management Act 1991 and in the MATTER of Application by Tararua Distric

BEFORE THE HEARING PANEL IN THE MATTER of the Resource Management Act 1991 AND IN THE MATTER of application by Tararua District Council to Horizons Regional Council for application APP-1993001253.02 for resource consents associated with the operation of the Pahiatua Wastewater Treatment Plant, including earthworks, a discharge to Town Creek (initially) then to the Mangatainoka River, a discharge to air (principally odour), and discharges to land via seepage, Julia Street, Pahiatua SUPPLEMENTARY EVIDENCE OF ADAM DOUGLAS CANNING (FRESHWATER ECOLOGY) FOR THE WELLINGTON FISH AND GAME COUNCIL 19 May 2017 1. My name is Adam Douglas Canning. I am a Freshwater Ecologist and my credentials are presented in my Evidence in Chief (EiC). Response to questions asked to me by the commissioners in Memorandum 3 To Participants (15 May 2017). 2. “In respect of Figure 1 on page 4 of Mr Canning’s evidence: i) Whereabouts in the Mangatainoka River were the Figure 1 measurements made? ii) If that is the type of pattern that might be caused by the Pahiatua WWTP discharge, how far downstream might it extend?” i) The diurnal dissolved oxygen fluctuations depicted in Figure 1 were made above shortly above the confluence with the Makakahi River (40˚28’36”S, 175˚47’14”N) (Wood et al., 2015). Therefore, the readings are well above, and consequently unaffected by, the Pahiatua Wastewater Treatment Plant (WWTP). The readings should not be taken as depicting the impact of the WWTP. Rather they show that a) the Mangatainoka River is in poor ecological health well before the WWTP; b) that extreme diurnal fluctuations in dissolved oxygen can and do occur in the Mangatainoka River; and c) increased nutrient inputs by the WWTP would likely exacerbate existing diurnal fluctuations and further reduce ecological health (as explained in my EiC). -

Te Kāuru Taiao Strategy

TE KĀURU EASTERN MANAWATŪ RIVER HAPŪ COLLECTIVE Te Kāuru Taiao Strategy TE KĀURU For The Eastern Manawatū River Catchment NOVEMBER 2016 First Edition: November 2016 Published by: Te Kāuru Eastern Manawatū River Hapū Collective 6 Ward Street PO Box 62 Dannevirke New Zealand Copyright © 2016 Te Kāuru Eastern Manawatū River Hapū Collective Acknowledgments The development of the ‘Te Kāuru Taiao Strategy’ is a tribute to all those who have been and those who are still collectively involved. This document provides strategies and actions for caring for the land, rivers, streams, all resident life within our environment, and our people in the Eastern Manawatū River Catchment. TE KĀURU EASTERN MANAWATŪ RIVER HAPŪ COLLECTIVE Te Kāuru Taiao Strategy Endorsements This strategy has been endorsed by the following 11 hapū of Te Kāuru who are shown with their respective tribal affiliation. A two tier rationale has been used (where required) to identify the Te Kāuru hapū members in terms of their customary connections with regards to their locality, occupation and connection with the Manawatū River and its tributaries: 1. Take ahikāroa 2. Tātai hono Ngāti Mārau (Rangitāne, Kahungunu) Ngāi Te Rangitotohu (Rangitāne, Kahungunu) Ngāi Tahu (Rangitāne, Kahungunu) Ngāti Ruatōtara (Rangitāne) Ngāti Te Opekai (Rangitāne) Ngāti Parakiore (Rangitāne) Ngāti Pakapaka (Rangitāne) Ngāti Mutuahi (Rangitāne) Ngāti Te Koro (Rangitāne) Te Kapuārangi (Rangitāne) Ngāti Hāmua (Rangitāne) Te Kāuru has hapū mana whenua membership of the Manawatū River Leaders’ Forum and will continue to support the ongoing efforts to restore and revitalise the mauri of the Manawatū River. Te Kāuru further support the integration of the Taiao Strategy into the wider Iwi/Hapū Management Plans. -

A Collaborative Approach to Transitions in Dannevirke

A collaborative approach to transitions in Dannevirke Lisa Bond, Jo Brown, Jenna Hutchings, and Sally Peters In this article we present some initial findings from a Teacherled Innovation Fund study undertaken in a kāhui ako based in the small community of Dannevirke. Teachers from the eight early childhood education (ECE) services and six schools have worked together to explore teacher practice and research the impact of teacher pedagogy on the transition, wellbeing, and academic engagement of tamariki in their community. The findings demonstrate that while, initially, there was little understanding or use of the other sector’s curriculum, teachers have been shar ing their knowledge and expertise across sectors, leading to deeper understandings of children’s learning and the links between curricula. Using knowledge gained, each setting has been working on its own goals. Two trends in these goals have been to enhance the confidence and independence of tamariki in ECE and offering playbased pedagogies in the new entrant classrooms. The study shows the power of teachers working across sectors and the possibilities when teachers come together to work for the benefit of tamariki across their whole community. Introduction Pathways section make specific links between the learn he role of teachers working across sectors to support ing outcomes of Te Whāriki and the school curriculum children’s transition to school has been a key focus documents, The New Zealand Curriculum (Ministry of Tnationally and internationally. For example, the Education, 2007) (NZC) and Te Marautanga o Aotearoa Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Develop (Ministry of Education, 2008). Similarly, a principle of ment (OECD) Starting Strong V report indicated that “qual NZC is coherence, and includes the expectation that the ity transitions should be wellprepared and childcentred, curriculum “provides for coherent transitions and opens managed by trained staff collaborating with one another, up pathways to future learning” (p. -

Tararua District Council Eketahuna Community Board

Tararua District Council Eketahuna Community Board Minutes of a meeting of the Eketahuna Community Board held in the Eketahuna Service Centre Meeting Room, 31 Main Street, Eketahuna on Friday 3 October, 2008 commencing at 10.05am. 1. Present Board Members J M Harman (Chairperson), C C Death (Deputy Chairperson), Elizabeth Fraser-Davies, K A M Dimock and Cr W H Davidson (Council appointed community board member). In Attendance Mr R Twentyman - Chief Executive Mr R Taylor - Governance Manager Mr C Veale - Community Assets Manager 2. Apologies 2.1 Nil 3. Personal Matters 3.1 Nil 4. Notification of Items Not on the Agenda 4.1 Nil 5. Confirmation of Minutes 5.1 That the minutes of the Eketahuna Community Board meeting held on 5 September, 2008 (as circulated) be confirmed as a true and accurate record of that meeting. Fraser-Davies/Death Carried 6. Matters Arising from the Minutes 6.1 Establishment of a Public Transport Coach Service From Masterton to Eketahuna (Item 5) 6.1.1 An informal survey will be included in the next Eketahuna community newsletter to ascertain possible support to establish a public transport service from Eketahuna to Masterton for shopping. 6.2 Mobile Recycling Bin (Item 7.1) 6.2.1 The area around the mobile recycling bin in Eketahuna is to be tidied, and a proposal is being considered to hot mix the surface. Eketahuna Community Board Minutes – 3 October, 2008 Page 1 6.2.2 The suggestion of relocating the recycling bin to the Community Centre car park is to be investigated, but this area may not be appropriate as the weight of the bin may rip the seal and make a mess. -

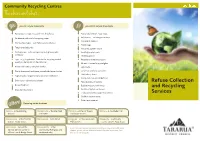

The Where and What

Community Recycling Centres The where and what... Yes you can recycle these items No you cannot recycle these items z Newspapers, magazines, junk mail, brochures z Household rubbish, food waste z Cardboard and non-foil wrapping paper z Polystyrene – including meat trays z Disposable nappies z Dry food packages – e.g. flattened cereal boxes z Plastic bags z Telephone directories z Hot ashes, garden waste z Writing paper, and envelopes (including those with z Seedling or plant pots windows) z Drinking glasses z Type 1, 2, 3, & 5 plastics – look for the recycling symbol, z Window or windscreen glass usually at the bottom of the container z Mirrors – frosted or crystal glass z Plastic milk bottles, soft drink bottles z Light bulbs z Plastic shampoo/conditioner, household cleaner bottles z Ceramics, crockery, porcelain z Old clothes, shoes z Yoghurt pots, margarine tubs, ice-cream containers z Computers, household batteries z Drink cans – aluminium and steel z Toys, buckets, or baskets Refuse Collection z Rinsed food tins z Bubble wrap or shrink wrap and Recycling z Glass bottles and jars z Paint tins, fuel oil containers z Containers/bottles larger than 4 litres Services z Shellfish and fish waste z Other toxic material Where Recycling centre locations Akitio – at the camping Herbertville – Tautane Road Pahiatua – corner of Queen Weber – at the Weber Hall ground intersetion and Tudor Streets Dannevirke – at the Transfer Norsewood – Odin Street Pongaroa – in the Community Woodville – Community Station, Easton Street Hall carpark Centre carpark, Ross Street Eketahuna – behind the Ormondville – at the If you have any queries regarding recycling, or any other solid waste Service Centre, corner of Community Hall (glass and matters, please call our Waste Services Contracts Supervisor, Pete Wilson Lane & Bridge Street cardboard only) Sinclair, on 06 374 4080. -

RESOURCE CONSENT DECISION New Zealand Transport Agency

RESOURCE CONSENT DECISION New Zealand Transport Agency (Transport Registry Centre Palmerston North) Decision on an application for resource consents to undertake vegetation clearance, land disturbance, discharge to water and drilling in the bed of a river for geotechnical investigations in and around the Manawatū River, Parahaki Island, and At-Risk, Rare and Threatened habitats adjacent to the Manawatū River, associated with Te Ahu a Tūranga - Manawatū Gorge Replacement at SH3, Palmerston North Application Reference: APP-2019202606.00 Decision Date: 26 February 2020 Expiry Date: 26 February 2022 Application Summary Proposal The New Zealand Transport Agency (the Applicant) has applied for resource consents to enable geotechnical investigations to inform the design and construction of the Te Ahu a Turanga (Manawatū Tararua Highway project). The Applicant has requested that the works be considered as two distinct locations as follows: 1. Up to six boreholes located to the immediate east of Parahaki Island, within the bed of the Manawatū River and the true left bank of the Manawatū River; and 2. Up to 13 boreholes located on land on the true right of the Manawatū River, and adjacent land on Raupo dominated seepage wetland and within Old Growth forest, which are considered to be At- Risk, Rare or Threatened habitats in Schedule F of the One Plan. The application notes that for some locations, 2-3 boreholes maybe required, with the final number being dependent on the geotechnical findings. The proposed location of the bore holes are shown in Figure one below. Figure 1 - Borehole locations The proposed boreholes are proposed to range between 0-70m in depth, with a casing size of 102mm. -

Benthic Cyanobacteria Blooms in Rivers in the Wellington Region Findings from a Decade of Monitoring and Research

Benthic cyanobacteria blooms in rivers in the Wellington Region Findings from a decade of monitoring and research Benthic cyanobacteria blooms in rivers in the Wellington Region Findings from a decade of monitoring and research MW Heath S Greenfield Environmental Science Department For more information, contact the Greater Wellington Regional Council: Wellington Masterton GW/ESCI-T-16/32 PO Box 11646 PO Box 41 ISBN: 978-1-927217-90-0 (print) ISBN: 978-1-927217-91-7 (online) T 04 384 5708 T 06 378 2484 F 04 385 6960 F 06 378 2146 June 2016 www.gw.govt.nz www.gw.govt.nz www.gw.govt.nz [email protected] Report prepared by: MW Heath Environmental Scientist S Greenfield Senior Environmental Scientist Report reviewed by: J Milne Team Leader, Aquatic Ecosystems & Quality Report approved for release by: L Butcher Manager, Environmental Science Date: June 2016 DISCLAIMER This report has been prepared by Environmental Science staff of Greater Wellington Regional Council (GWRC) and as such does not constitute Council policy. In preparing this report, the authors have used the best currently available data and have exercised all reasonable skill and care in presenting and interpreting these data. Nevertheless, GWRC does not accept any liability, whether direct, indirect, or consequential, arising out of the provision of the data and associated information within this report. Furthermore, as GWRC endeavours to continuously improve data quality, amendments to data included in, or used in the preparation of, this report may occur without notice at any time. GWRC requests that if excerpts or inferences are drawn from this report for further use, due care should be taken to ensure the appropriate context is preserved and is accurately reflected and referenced in subsequent written or verbal communications.