Patterns of Animal Utilization in the Holocene of the Philippines: a Comparison of Faunal Samples from Four Archaeological Sites

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fossil Bovidae from the Malay Archipelago and the Punjab

FOSSIL BOVIDAE FROM THE MALAY ARCHIPELAGO AND THE PUNJAB by Dr. D. A. HOOIJER (Rijksmuseum van Natuurlijke Historie, Leiden) with pls. I-IX CONTENTS Introduction 1 Order Artiodactyla Owen 8 Family Bovidae Gray 8 Subfamily Bovinae Gill 8 Duboisia santeng (Dubois) 8 Epileptobos groeneveldtii (Dubois) 19 Hemibos triquetricornis Rütimeyer 60 Hemibos acuticornis (Falconer et Cautley) 61 Bubalus palaeokerabau Dubois 62 Bubalus bubalis (L.) subsp 77 Bibos palaesondaicus Dubois 78 Bibos javanicus (d'Alton) subsp 98 Subfamily Caprinae Gill 99 Capricornis sumatraensis (Bechstein) subsp 99 Literature cited 106 Explanation of the plates 11o INTRODUCTION The Bovidae make up a very large portion of the Dubois collection of fossil vertebrates from Java, second only to the Proboscidea in bulk. Before Dubois began his explorations in Java in 1890 we knew very little about the fossil bovids of that island. Martin (1887, p. 61, pl. VII fig. 2) described a horn core as Bison sivalensis Falconer (?); Bison sivalensis Martin has al• ready been placed in the synonymy of Bibos palaesondaicus Dubois by Von Koenigswald (1933, p. 93), which is evidently correct. Pilgrim (in Bron- gersma, 1936, p. 246) considered the horn core in question to belong to a Bibos species closely related to the banteng. Two further horn cores from Java described by Martin (1887, p. 63, pl. VI fig. 4; 1888, p. 114, pl. XII fig. 4) are not sufficiently well preserved to allow of a specific determination, although they probably belong to Bibos palaesondaicus Dubois as well. In a preliminary faunal list Dubois (1891) mentions four bovid species as occurring in the Pleistocene of Java, viz., two living species (the banteng and the water buffalo) and two extinct forms, Anoa spec. -

Conservation Status of Asiatic Wild Buffalo (Bubalus Arnee) in Chhattisgarh

Conservation status of Asiatic Wild Buffalo (Bubalus arnee) in Chhattisgarh revealed through genetic study A Technical Report Prepared by Laboratory for the Conservation of Wildlife Trust of India Endangered Species(LACONES) F – 13, Sector 08 CSIR-CCMB Annex I, HYDERABAD – 500048 NCR, Noida - 201301 Disclaimer: This publication is meant for authorized use by laboratories and persons involved in research on conservation of Wild buffalos. LaCONES shall not be liable for any direct, consequential or incidental damages arising out of the protocols described in this book. Reference to any specific product (commercial or non-commercial), processes or services by brand or trade name, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise does not necessarily constitute or imply its endorsement, recommendation or favor by LaCONES. The information and statements contained in this document shall not be used for the purpose of advertising or to imply the endorsement or recommendation of LaCONES. Citation: Mishra R.P. and A. Gaur. 2019. Conservation status of Asiatic Wild Buffalo (Bubalus arnee) in Chhattisgarh revealed through genetic study. Technical Report of WTI and CSIR-CCMB, 17p ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS We are thankful to the Forest Department, Govt. of Chhattisgarh for giving permission to carry out the conservation and research activities on Wild buffalo in various protected areas in Chhattisgarh. We are grateful to Shri Ram Prakash, PCCF (Retd.); Shri R.N. Mishra, PCCF (Retd.); Dr. R.K. Singh, PCCF (Retd.), Shri Atul Kumar Shukla, Principal Chief Conservator of Forests & Chief Wildlife Warden and Dr. S.K. Singh, Additional Principal Chief Conservator of Forests (WL), Dr. Rakesh Mishra, Director CSIR-CCMB, Dr. Rahul Kaul, Executive Director, WTI, Dr. -

A Bubaline-Derived Satellite DNA Probe Uncovers Generic Affinities of Gaur with Other Bovids

A bubaline-derived satellite DNA probe uncovers generic affinities of gaur with other bovids PRITHA RAY, SUPRIYA GANGADHARAN, MUNMUN CHATrOPADHYAY, ANU BASHAMBOO, SUN1TA BHATNAGAR, PRADEEP KUMAR MALIK* and SHER ALI t Molecular Genetics Laboratory, National Institute of Immunology, Aruna Asaf Ali Marg, New Delhi 110 067, India *Wildlife Institute of lndia, Chandrabani, Dehra Dun 248 001, India tCorresponding author (Fax, 91-11-6162125; Email, [email protected]). DNA typing using genome derived cloned probes may be conducted for ascertaining genetic affinities of closely related species. We analysed gaur Bos gaurus, cattle Bos indicus, buffalo Bubalus bubalis, sheep Ovis aries and goat Capra hircus DNA using buffalo derived cloned probe pDS5 carrying an array of BamHI satellite fraction of 1378 base residues to uncover its genomic organization. Zoo-blot analysis showed that pDS5 does not cross hybridize with non-bovid animals and surprisingly with female gaur genomic DNA. The presence of pDS5 sequences in the gaur males suggests their possible location on the Y chromosome. Genotyping of pDS5 with BamHI enzyme detected mostly monomorphic bands in the bubaline samples and polymorphic ones in cattle and gaur giving rise to clad specific pattern. Similar typing with RsaI enzyme also revealed clad specific band pattern detecting more number of bands in buffalo and fewer in sheep, goat and gaur samples. Copy number variation was found to be prominent in cattle and gaur with RsaI typing. Our data based on matched band profiles (MBP) suggest that gaur is genetically closer to cattle than buffalo contradicting the age-old notion held by some that gaur is a wild buffalo. -

Vega Etal Procroyalsocb Synchronous Diversification

Canterbury Christ Church University’s repository of research outputs http://create.canterbury.ac.uk Please cite this publication as follows: Frantz, Laurent A. F., Rudzinski, A., Mansyursyah Surya Nugraha, A., Evin, A., Burton, J., Hulme-Beaman, A., Linderholm, A., Barnett, R., Vega, R., Irving-Pease, E., Haile, J., Allen, R., Leus, K., Shephard, J., Hillyer, M., Gillemot, S., van den Hurk, J., Ogle, S., Atofanei, C., Thomas, M., Johansson, F., Haris Mustari, A., Williams, J., Mohamad, K., Siska Damayanti, C., Djuwita Wiryadi, I., Obbles, D., Mona, S., Day, H., Yasin, M., Meker, S., McGuire, J., Evans, B., von Rintelen, T., Hoult, S., Searle, J., Kitchener, A., Macdonald, A., Shaw, D., Hall, R., Galbusera, P. and Larson, G. (2018) Synchronous diversification of Sulawesi’s iconic artiodactyls driven by recent geological events. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. Link to official URL (if available): http://dx.doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2017.2566. This version is made available in accordance with publishers’ policies. All material made available by CReaTE is protected by intellectual property law, including copyright law. Any use made of the contents should comply with the relevant law. Contact: [email protected] Synchronous diversification of Sulawesi’s iconic artiodactyls driven by recent geological events Authors Laurent A. F. Frantz1,2,a,*, Anna Rudzinski3,*, Abang Mansyursyah Surya Nugraha4,c,*, , Allowen Evin5,6*, James Burton7,8*, Ardern Hulme-Beaman2,6, Anna Linderholm2,9, Ross Barnett2,10, Rodrigo Vega11 Evan K. Irving-Pease2, James Haile2,10, Richard Allen2, Kristin Leus12,13, Jill Shephard14,15, Mia Hillyer14,16, Sarah Gillemot14, Jeroen van den Hurk14, Sharron Ogle17, Cristina Atofanei11, Mark G. -

Cebu-Ebook.Pdf

About Cebu .........................................................................................................................................2 Sinulog festival....................................................................................................................................3 Cebu Facts and Figures .....................................................................................................................4 Cebu Province Towns & Municipalities...........................................................................................5 Sites About Cebu and Cebu City ......................................................................................................6 Cebu Island, Malapascus, Moalboal Dive Sites...............................................................................8 Cebu City Hotels...............................................................................................................................10 Lapu Lapu Hotels.............................................................................................................................13 Mactan Island Hotels and Resorts..................................................................................................14 Safety Travel Tips ............................................................................................................................16 Cebu City ( Digital pdf Map ) .........................................................................................................17 Mactan Island ( Digital -

Detomidine and Butorphanol for Standing Sedation in a Range of Zoo-Kept Ungulate Species

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Ghent University Academic Bibliography Journal of Zoo and Wildlife Medicine 48(3): 616–626, 2017 Copyright 2017 by American Association of Zoo Veterinarians DETOMIDINE AND BUTORPHANOL FOR STANDING SEDATION IN A RANGE OF ZOO-KEPT UNGULATE SPECIES Tim Bouts, D.V.M., M.Sc., Dip. E.C.Z.M., Joanne Dodds, V.N., Karla Berry, V.N., Abdi Arif, M.V.Sc., Polly Taylor, Vet. M. B., Ph. D., Dip. E.C.V.A.A., Andrew Routh, B. V. Sc., Cert. Zoo. Med., and Frank Gasthuys, D.V.M., Ph. D., Dip. E.C.V.A.A. Abstract: General anesthesia poses risks for larger zoo species, like cardiorespiratory depression, myopathy, and hyperthermia. In ruminants, ruminal bloat and regurgitation of rumen contents with potential aspiration pneumonia are added risks. Thus, the use of sedation to perform minor procedures is justified in zoo animals. A combination of detomidine and butorphanol has been routinely used in domestic animals. This drug combination, administered by remote intramuscular injection, can also be applied for standing sedation in a range of zoo animals, allowing a number of minor procedures. The combination was successfully administered in five species of nondomesticated equids (Przewalski horse [Equus ferus przewalskii; n ¼ 1], onager [Equus hemionus onager; n ¼ 4], kiang [Equus kiang; n ¼ 3], Grevy’s zebra [Equus grevyi; n ¼ 4], and Somali wild ass [Equus africanus somaliensis; n ¼ 7]), with a mean dose range of 0.10–0.17 mg/kg detomidine and 0.07–0.13 mg/kg butorphanol; the white (Ceratotherium simum simum; n ¼ 12) and greater one-horned rhinoceros (Rhinoceros unicornis; n ¼ 4), with a mean dose of 0.015 mg/kg of both detomidine and butorphanol; and Asiatic elephant bulls (Elephas maximus; n ¼ 2), with a mean dose of 0.018 mg/kg of both detomidine and butorphanol. -

(Bubalus Bubalis) in NEPAL: RECOMMENDED MANAGEMENT ACTION in the FACE of UNCERTAINTY for a CRITICALLY ENDANGERED SPECIES

Contents TIGERPAPER A Translocation Proposal for Wild Buffalo in Nepal................... 1 Eucalyptus – Bane or Boon?................................................... 8 Status and Distribution of Wild Cattle in Cambodia.................... 9 Reptile Richness and Diversity In and Around Gir Forest........... 15 A Comparison of Identification Techniques for Predators on Artificial Nests................................................................... 20 Devastating Flood in Kaziranga National Park............................ 24 Bird Damage to Guava and Papaya........................................... 27 Death of an Elephant by Sunstroke in Orissa............................. 31 Msc in Forest and Nature Conservation for Tropical Areas......... 32 FOREST NEWS Report of an International Conference on Community Involvement in Fire Management............................................ 1 ASEAN Senior Officials Endorse Code of Practice for Forest Harvesting.................................................................. 4 Asian Model Forests Develop Criteria and Indicators Guidelines............................................................................. 4 East Asian Countries Pledge Action on Illegal Forest Activities.............................................................................. 6 South Pacific Ministers Consider Forestry Issues........................ 9 Tropical Ecosystems, Structure, Diversity and Human Welfare.. 10 Draft Webpage for International Weem Network......................... 10 New FAO Forestry Publications............................................... -

Pan-American Trypanosoma (Megatrypanum) Trinaperronei N. Sp

Garcia et al. Parasites Vectors (2020) 13:308 https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-020-04169-0 Parasites & Vectors RESEARCH Open Access Pan-American Trypanosoma (Megatrypanum) trinaperronei n. sp. in the white-tailed deer Odocoileus virginianus Zimmermann and its deer ked Lipoptena mazamae Rondani, 1878: morphological, developmental and phylogeographical characterisation Herakles A. Garcia1,2* , Pilar A. Blanco2,3,4, Adriana C. Rodrigues1, Carla M. F. Rodrigues1,5, Carmen S. A. Takata1, Marta Campaner1, Erney P. Camargo1,5 and Marta M. G. Teixeira1,5* Abstract Background: The subgenus Megatrypanum Hoare, 1964 of Trypanosoma Gruby, 1843 comprises trypanosomes of cervids and bovids from around the world. Here, the white-tailed deer Odocoileus virginianus (Zimmermann) and its ectoparasite, the deer ked Lipoptena mazamae Rondani, 1878 (hippoboscid fy), were surveyed for trypanosomes in Venezuela. Results: Haemoculturing unveiled 20% infected WTD, while 47% (7/15) of blood samples and 38% (11/29) of ked guts tested positive for the Megatrypanum-specifc TthCATL-PCR. CATL and SSU rRNA sequences uncovered a single species of trypanosome. Phylogeny based on SSU rRNA and gGAPDH sequences tightly cluster WTD trypanosomes from Venezuela and the USA, which were strongly supported as geographical variants of the herein described Trypa- nosoma (Megatrypanum) trinaperronei n. sp. In our analyses, the new species was closest to Trypanosoma sp. D30 from fallow deer (Germany), both nested into TthII alongside other trypanosomes from cervids (North American elk and European fallow, red and sika deer), and bovids (cattle, antelopes and sheep). Insights into the life-cycle of T. trinaper- ronei n. sp. were obtained from early haemocultures of deer blood and co-culture with mammalian and insect cells showing fagellates resembling Megatrypanum trypanosomes previously reported in deer blood, and deer ked guts. -

Mixed-Species Exhibits with Pigs (Suidae)

Mixed-species exhibits with Pigs (Suidae) Written by KRISZTIÁN SVÁBIK Team Leader, Toni’s Zoo, Rothenburg, Luzern, Switzerland Email: [email protected] 9th May 2021 Cover photo © Krisztián Svábik Mixed-species exhibits with Pigs (Suidae) 1 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................... 3 Use of space and enclosure furnishings ................................................................... 3 Feeding ..................................................................................................................... 3 Breeding ................................................................................................................... 4 Choice of species and individuals ............................................................................ 4 List of mixed-species exhibits involving Suids ........................................................ 5 LIST OF SPECIES COMBINATIONS – SUIDAE .......................................................... 6 Sulawesi Babirusa, Babyrousa celebensis ...............................................................7 Common Warthog, Phacochoerus africanus ......................................................... 8 Giant Forest Hog, Hylochoerus meinertzhageni ..................................................10 Bushpig, Potamochoerus larvatus ........................................................................ 11 Red River Hog, Potamochoerus porcus ............................................................... -

The Water Buffalo: Domestic Anima of the Future

The Water Buffalo: Domestic Anima © CopyrightAmerican Association o fBovine Practitioners; open access distribution. of the Future W. Ross Cockrill, D.V.M., F.R.C.V.S., Consultant, Animal Production, Protection & Health, Food and Agriculture Organization Rome, Italy Summary to produce the cattalo, or beefalo, a heavy meat- The water buffalo (Bubalus bubalis) is a type animal for which widely publicized claims neglected bovine animal with a notable and so far have been made. The water buffalo has never been unexploited potential, especially for meat and shown to produce offspring either fertile or sterile milk production. World buffalo stocks, which at when mated with cattle, although under suitable present total 150 million in some 40 countries, are conditions a bull will serve female buffaloes, while increasing steadily. a male buffalo will mount cows. It is important that national stocks should be There are about 150 million water buffaloes in the upgraded by selective breeding allied to improved world compared to a cattle population of around 1,- management and nutrition but, from the stand 165 million. This is a significant figure, especially point of increased production and the full realiza when it is considered that the majority of buffaloes tion of potential, it is equally important that are productive in terms of milk, work and meat, or crossbreeding should be carried out extensively any two of these outputs, whereas a high proportion of especially in association with schemes to increase the world’s cattle is economically useless. and improve buffalo meat production. In the majority of buffalo-owning countries, and in Meat from buffaloes which are reared and fed all those in which buffaloes make an important con for early slaughter is of excellent quality. -

The Cosmological Role of the Pig in the Kelabit Highlands, Sarawak

anthropozoologica 2021 ● 56 ● 11 LES SUIDÉS EN CONTEXTE RITUEL À L’ÉPOQUE CONTEMPORAINE Édité par Frédéric LAUGRAND, Lionel SIMON & Séverine LAGNEAUX Prey into kin: the cosmological role of the pig in the Kelabit Highlands, Sarawak Monica JANOWSKI art. 56 (11) — Published on 6 August 2021 www.anthropozoologica.com DIRECTEUR DE LA PUBLICATION / PUBLICATION DIRECTOR : Bruno David Président du Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle RÉDACTRICE EN CHEF / EDITOR-IN-CHIEF: Joséphine Lesur RÉDACTRICE / EDITOR: Christine Lefèvre RESPONSABLE DES ACTUALITÉS SCIENTIFIQUES / RESPONSIBLE FOR SCIENTIFIC NEWS: Rémi Berthon ASSISTANTE DE RÉDACTION / ASSISTANT EDITOR: Emmanuelle Rocklin ([email protected]) MISE EN PAGE / PAGE LAYOUT: Emmanuelle Rocklin, Inist-CNRS COMITÉ SCIENTIFIQUE / SCIENTIFIC BOARD: Louis Chaix (Muséum d’Histoire naturelle, Genève, Suisse) Jean-Pierre Digard (CNRS, Ivry-sur-Seine, France) Allowen Evin (Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle, Paris, France) Bernard Faye (Cirad, Montpellier, France) Carole Ferret (Laboratoire d’Anthropologie Sociale, Paris, France) Giacomo Giacobini (Università di Torino, Turin, Italie) Lionel Gourichon (Université de Nice, Nice, France) Véronique Laroulandie (CNRS, Université de Bordeaux 1, France) Stavros Lazaris (Orient & Méditerranée, Collège de France – CNRS – Sorbonne Université, Paris, France) Nicolas Lescureux (Centre d'Écologie fonctionnelle et évolutive, Montpellier, France) Marco Masseti (University of Florence, Italy) Georges Métailié (Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle, Paris, France) Diego -

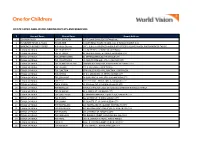

List of Ecpay Cash-In Or Loading Outlets and Branches

LIST OF ECPAY CASH-IN OR LOADING OUTLETS AND BRANCHES # Account Name Branch Name Branch Address 1 ECPAY-IBM PLAZA ECPAY- IBM PLAZA 11TH FLOOR IBM PLAZA EASTWOOD QC 2 TRAVELTIME TRAVEL & TOURS TRAVELTIME #812 EMERALD TOWER JP RIZAL COR. P.TUAZON PROJECT 4 QC 3 ABONIFACIO BUSINESS CENTER A Bonifacio Stopover LOT 1-BLK 61 A. BONIFACIO AVENUE AFP OFFICERS VILLAGE PHASE4, FORT BONIFACIO TAGUIG 4 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP_HEAD OFFICE 170 SALCEDO ST. LEGASPI VILLAGE MAKATI 5 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP_BF HOMES 43 PRESIDENTS AVE. BF HOMES, PARANAQUE CITY 6 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP_BETTER LIVING 82 BETTERLIVING SUBD.PARANAQUE CITY 7 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP_COUNTRYSIDE 19 COUNTRYSIDE AVE., STA. LUCIA PASIG CITY 8 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP_GUADALUPE NUEVO TANHOCK BUILDING COR. EDSA GUADALUPE MAKATI CITY 9 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP_HERRAN 111 P. GIL STREET, PACO MANILA 10 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP_JUNCTION STAR VALLEY PLAZA MALL JUNCTION, CAINTA RIZAL 11 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP_RETIRO 27 N.S. AMORANTO ST. RETIRO QUEZON CITY 12 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP_SUMULONG 24 SUMULONG HI-WAY, STO. NINO MARIKINA CITY 13 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP 10TH 245- B 1TH AVE. BRGY.6 ZONE 6, CALOOCAN CITY 14 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP B. BARRIO 35 MALOLOS AVE, B. BARRIO CALOOCAN CITY 15 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP BUSTILLOS TIWALA SA PADALA L2522- 28 ROAD 216, EARNSHAW BUSTILLOS MANILA 16 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP CALOOCAN 43 A. MABINI ST. CALOOCAN CITY 17 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP CONCEPCION 19 BAYAN-BAYANAN AVE. CONCEPCION, MARIKINA CITY 18 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP JP RIZAL 529 OLYMPIA ST. JP RIZAL QUEZON CITY 19 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP LALOMA 67 CALAVITE ST.