MAT 101 How to Analyze a Symbolic Argument Criterion for Validity. An

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chrysippus's Dog As a Case Study in Non-Linguistic Cognition

Chrysippus’s Dog as a Case Study in Non-Linguistic Cognition Michael Rescorla Abstract: I critique an ancient argument for the possibility of non-linguistic deductive inference. The argument, attributed to Chrysippus, describes a dog whose behavior supposedly reflects disjunctive syllogistic reasoning. Drawing on contemporary robotics, I urge that we can equally well explain the dog’s behavior by citing probabilistic reasoning over cognitive maps. I then critique various experimentally-based arguments from scientific psychology that echo Chrysippus’s anecdotal presentation. §1. Language and thought Do non-linguistic creatures think? Debate over this question tends to calcify into two extreme doctrines. The first, espoused by Descartes, regards language as necessary for cognition. Modern proponents include Brandom (1994, pp. 145-157), Davidson (1984, pp. 155-170), McDowell (1996), and Sellars (1963, pp. 177-189). Cartesians may grant that ascribing cognitive activity to non-linguistic creatures is instrumentally useful, but they regard such ascriptions as strictly speaking false. The second extreme doctrine, espoused by Gassendi, Hume, and Locke, maintains that linguistic and non-linguistic cognition are fundamentally the same. Modern proponents include Fodor (2003), Peacocke (1997), Stalnaker (1984), and many others. Proponents may grant that non- linguistic creatures entertain a narrower range of thoughts than us, but they deny any principled difference in kind.1 2 An intermediate position holds that non-linguistic creatures display cognitive activity of a fundamentally different kind than human thought. Hobbes and Leibniz favored this intermediate position. Modern advocates include Bermudez (2003), Carruthers (2002, 2004), Dummett (1993, pp. 147-149), Malcolm (1972), and Putnam (1992, pp. 28-30). -

The Validities of Pep and Some Characteristic Formulas in Modal Logic

THE VALIDITIES OF PEP AND SOME CHARACTERISTIC FORMULAS IN MODAL LOGIC Hong Zhang, Huacan He School of Computer Science, Northwestern Polytechnical University,Xi'an, Shaanxi 710032, P.R. China Abstract: In this paper, we discuss the relationships between some characteristic formulas in normal modal logic with their frames. We find that the validities of the modal formulas are conditional even though some of them are intuitively valid. Finally, we prove the validities of two formulas of Position- Exchange-Principle (PEP) proposed by papers 1 to 3 by using of modal logic and Kripke's semantics of possible worlds. Key words: Characteristic Formulas, Validity, PEP, Frame 1. INTRODUCTION Reasoning about knowledge and belief is an important issue in the research of multi-agent systems, and reasoning, which is set up from the main ideas of situational calculus, about other agents' states and actions is one of the most important directions in Al^^'^\ Papers [1-3] put forward an axiom scheme in reasoning about others(RAO) in multi-agent systems, and a rule called Position-Exchange-Principle (PEP), which is shown as following, was abstracted . C{(p^y/)^{C(p->Cy/) (Ce{5f',...,5f-}) When the length of C is at least 2, it reflects the mechanism of an agent reasoning about knowledge of others. For example, if C is replaced with Bf B^/, then it should be B':'B]'{(p^y/)-^iBf'B]'(p^Bf'B]'y/) 872 Hong Zhang, Huacan He The axiom schema plays a useful role as that of modus ponens and axiom K when simplifying proof. Though examples were demonstrated as proofs in papers [1-3], from the perspectives both in semantics and in syntax, the rule is not so compellent. -

Section 2.1: Proof Techniques

Section 2.1: Proof Techniques January 25, 2021 Abstract Sometimes we see patterns in nature and wonder if they hold in general: in such situations we are demonstrating the appli- cation of inductive reasoning to propose a conjecture, which may become a theorem which we attempt to prove via deduc- tive reasoning. From our work in Chapter 1, we conceive of a theorem as an argument of the form P → Q, whose validity we seek to demonstrate. Example: A student was doing a proof and suddenly specu- lated “Couldn’t we just say (A → (B → C)) ∧ B → (A → C)?” Can she? It’s a theorem – either we prove it, or we provide a counterexample. This section outlines a variety of proof techniques, including direct proofs, proofs by contraposition, proofs by contradiction, proofs by exhaustion, and proofs by dumb luck or genius! You have already seen each of these in Chapter 1 (with the exception of “dumb luck or genius”, perhaps). 1 Theorems and Informal Proofs The theorem-forming process is one in which we • make observations about nature, about a system under study, etc.; • discover patterns which appear to hold in general; • state the rule; and then • attempt to prove it (or disprove it). This process is formalized in the following definitions: • inductive reasoning - drawing a conclusion based on experi- ence, which one might state as a conjecture or theorem; but al- mostalwaysas If(hypotheses)then(conclusion). • deductive reasoning - application of a logic system to investi- gate a proposed conclusion based on hypotheses (hence proving, disproving, or, failing either, holding in limbo the conclusion). -

On Basic Probability Logic Inequalities †

mathematics Article On Basic Probability Logic Inequalities † Marija Boriˇci´cJoksimovi´c Faculty of Organizational Sciences, University of Belgrade, Jove Ili´ca154, 11000 Belgrade, Serbia; [email protected] † The conclusions given in this paper were partially presented at the European Summer Meetings of the Association for Symbolic Logic, Logic Colloquium 2012, held in Manchester on 12–18 July 2012. Abstract: We give some simple examples of applying some of the well-known elementary probability theory inequalities and properties in the field of logical argumentation. A probabilistic version of the hypothetical syllogism inference rule is as follows: if propositions A, B, C, A ! B, and B ! C have probabilities a, b, c, r, and s, respectively, then for probability p of A ! C, we have f (a, b, c, r, s) ≤ p ≤ g(a, b, c, r, s), for some functions f and g of given parameters. In this paper, after a short overview of known rules related to conjunction and disjunction, we proposed some probabilized forms of the hypothetical syllogism inference rule, with the best possible bounds for the probability of conclusion, covering simultaneously the probabilistic versions of both modus ponens and modus tollens rules, as already considered by Suppes, Hailperin, and Wagner. Keywords: inequality; probability logic; inference rule MSC: 03B48; 03B05; 60E15; 26D20; 60A05 1. Introduction The main part of probabilization of logical inference rules is defining the correspond- Citation: Boriˇci´cJoksimovi´c,M. On ing best possible bounds for probabilities of propositions. Some of them, connected with Basic Probability Logic Inequalities. conjunction and disjunction, can be obtained immediately from the well-known Boole’s Mathematics 2021, 9, 1409. -

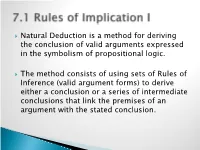

7.1 Rules of Implication I

Natural Deduction is a method for deriving the conclusion of valid arguments expressed in the symbolism of propositional logic. The method consists of using sets of Rules of Inference (valid argument forms) to derive either a conclusion or a series of intermediate conclusions that link the premises of an argument with the stated conclusion. The First Four Rules of Inference: ◦ Modus Ponens (MP): p q p q ◦ Modus Tollens (MT): p q ~q ~p ◦ Pure Hypothetical Syllogism (HS): p q q r p r ◦ Disjunctive Syllogism (DS): p v q ~p q Common strategies for constructing a proof involving the first four rules: ◦ Always begin by attempting to find the conclusion in the premises. If the conclusion is not present in its entirely in the premises, look at the main operator of the conclusion. This will provide a clue as to how the conclusion should be derived. ◦ If the conclusion contains a letter that appears in the consequent of a conditional statement in the premises, consider obtaining that letter via modus ponens. ◦ If the conclusion contains a negated letter and that letter appears in the antecedent of a conditional statement in the premises, consider obtaining the negated letter via modus tollens. ◦ If the conclusion is a conditional statement, consider obtaining it via pure hypothetical syllogism. ◦ If the conclusion contains a letter that appears in a disjunctive statement in the premises, consider obtaining that letter via disjunctive syllogism. Four Additional Rules of Inference: ◦ Constructive Dilemma (CD): (p q) • (r s) p v r q v s ◦ Simplification (Simp): p • q p ◦ Conjunction (Conj): p q p • q ◦ Addition (Add): p p v q Common Misapplications Common strategies involving the additional rules of inference: ◦ If the conclusion contains a letter that appears in a conjunctive statement in the premises, consider obtaining that letter via simplification. -

'The Denial of Bivalence Is Absurd'1

On ‘The Denial of Bivalence is Absurd’1 Francis Jeffry Pelletier Robert J. Stainton University of Alberta Carleton University Edmonton, Alberta, Canada Ottawa, Ontario, Canada [email protected] [email protected] Abstract: Timothy Williamson, in various places, has put forward an argument that is supposed to show that denying bivalence is absurd. This paper is an examination of the logical force of this argument, which is found wanting. I. Introduction Let us being with a word about what our topic is not. There is a familiar kind of argument for an epistemic view of vagueness in which one claims that denying bivalence introduces logical puzzles and complications that are not easily overcome. One then points out that, by ‘going epistemic’, one can preserve bivalence – and thus evade the complications. James Cargile presented an early version of this kind of argument [Cargile 1969], and Tim Williamson seemingly makes a similar point in his paper ‘Vagueness and Ignorance’ [Williamson 1992] when he says that ‘classical logic and semantics are vastly superior to…alternatives in simplicity, power, past success, and integration with theories in other domains’, and contends that this provides some grounds for not treating vagueness in this way.2 Obviously an argument of this kind invites a rejoinder about the puzzles and complications that the epistemic view introduces. Here are two quick examples. First, postulating, as the epistemicist does, linguistic facts no speaker of the language could possibly know, and which have no causal link to actual or possible speech behavior, is accompanied by a litany of disadvantages – as the reader can imagine. -

Three Ways of Being Non-Material

Three Ways of Being Non-Material Vincenzo Crupi, Andrea Iacona May 2019 This paper presents a novel unified account of three distinct non-material inter- pretations of `if then': the suppositional interpretation, the evidential interpre- tation, and the strict interpretation. We will spell out and compare these three interpretations within a single formal framework which rests on fairly uncontro- versial assumptions, in that it requires nothing but propositional logic and the probability calculus. As we will show, each of the three intrerpretations exhibits specific logical features that deserve separate consideration. In particular, the evidential interpretation as we understand it | a precise and well defined ver- sion of it which has never been explored before | significantly differs both from the suppositional interpretation and from the strict interpretation. 1 Preliminaries Although it is widely taken for granted that indicative conditionals as they are used in ordinary language do not behave as material conditionals, there is little agreement on the nature and the extent of such deviation. Different theories tend to privilege different intuitions about conditionals, and there is no obvious answer to the question of which of them is the correct theory. In this paper, we will compare three interpretations of `if then': the suppositional interpretation, the evidential interpretation, and the strict interpretation. These interpretations may be regarded either as three distinct meanings that ordinary speakers attach to `if then', or as three ways of explicating a single indeterminate meaning by replacing it with a precise and well defined counterpart. Here is a rough and informal characterization of the three interpretations. According to the suppositional interpretation, a conditional is acceptable when its consequent is credible enough given its antecedent. -

The Incorrect Usage of Propositional Logic in Game Theory

The Incorrect Usage of Propositional Logic in Game Theory: The Case of Disproving Oneself Holger I. MEINHARDT ∗ August 13, 2018 Recently, we had to realize that more and more game theoretical articles have been pub- lished in peer-reviewed journals with severe logical deficiencies. In particular, we observed that the indirect proof was not applied correctly. These authors confuse between statements of propositional logic. They apply an indirect proof while assuming a prerequisite in order to get a contradiction. For instance, to find out that “if A then B” is valid, they suppose that the assumptions “A and not B” are valid to derive a contradiction in order to deduce “if A then B”. Hence, they want to establish the equivalent proposition “A∧ not B implies A ∧ notA” to conclude that “if A then B”is valid. In fact, they prove that a truth implies a falsehood, which is a wrong statement. As a consequence, “if A then B” is invalid, disproving their own results. We present and discuss some selected cases from the literature with severe logical flaws, invalidating the articles. Keywords: Transferable Utility Game, Solution Concepts, Axiomatization, Propositional Logic, Material Implication, Circular Reasoning (circulus in probando), Indirect Proof, Proof by Contradiction, Proof by Contraposition, Cooperative Oligopoly Games 2010 Mathematics Subject Classifications: 03B05, 91A12, 91B24 JEL Classifications: C71 arXiv:1509.05883v1 [cs.GT] 19 Sep 2015 ∗Holger I. Meinhardt, Institute of Operations Research, Karlsruhe Institute of Technology (KIT), Englerstr. 11, Building: 11.40, D-76128 Karlsruhe. E-mail: [email protected] The Incorrect Usage of Propositional Logic in Game Theory 1 INTRODUCTION During the last decades, game theory has encountered a great success while becoming the major analysis tool for studying conflicts and cooperation among rational decision makers. -

Conundrums of Conditionals in Contraposition

Dale Jacquette CONUNDRUMS OF CONDITIONALS IN CONTRAPOSITION A previously unnoticed metalogical paradox about contrapo- sition is formulated in the informal metalanguage of propositional logic, where it exploits a reflexive self-non-application of the truth table definition of the material conditional to achieve semantic di- agonalization. Three versions of the paradox are considered. The main modal formulation takes as its assumption a conditional that articulates the truth table conditions of conditional propo- sitions in stating that if the antecedent of a true conditional is false, then it is possible for its consequent to be true. When this true conditional is contraposed in the conclusion of the inference, it produces the false conditional conclusion that if it is not the case that the consequent of a true conditional can be true, then it is not the case that the antecedent of the conditional is false. 1. The Logic of Conditionals A conditional sentence is the literal contrapositive of another con- ditional if and only if the antecedent of one is the negation of the consequent of the other. The sentence q p is thus ordinarily un- derstood as the literal contrapositive of: p⊃ :q. But the requirement presupposes that the unnegated antecedents⊃ of the conditionals are identical in meaning to the unnegated consequents of their contrapos- itives. The univocity of ‘p’ and ‘q’ in p q and q p can usually be taken for granted within a single context⊃ of: application⊃ : in sym- bolic logic, but in ordinary language the situation is more complicated. To appreciate the difficulties, consider the use of potentially equivo- cal terms in the following conditionals whose reference is specified in particular speech act contexts: (1.1) If the money is in the bank, then the money is safe. -

The Substitutional Analysis of Logical Consequence

THE SUBSTITUTIONAL ANALYSIS OF LOGICAL CONSEQUENCE Volker Halbach∗ dra version ⋅ please don’t quote ónd June óþÕä Consequentia ‘formalis’ vocatur quae in omnibus terminis valet retenta forma consimili. Vel si vis expresse loqui de vi sermonis, consequentia formalis est cui omnis propositio similis in forma quae formaretur esset bona consequentia [...] Iohannes Buridanus, Tractatus de Consequentiis (Hubien ÕÉßä, .ì, p.óóf) Zf«±§Zh± A substitutional account of logical truth and consequence is developed and defended. Roughly, a substitution instance of a sentence is dened to be the result of uniformly substituting nonlogical expressions in the sentence with expressions of the same grammatical category. In particular atomic formulae can be replaced with any formulae containing. e denition of logical truth is then as follows: A sentence is logically true i all its substitution instances are always satised. Logical consequence is dened analogously. e substitutional denition of validity is put forward as a conceptual analysis of logical validity at least for suciently rich rst-order settings. In Kreisel’s squeezing argument the formal notion of substitutional validity naturally slots in to the place of informal intuitive validity. ∗I am grateful to Beau Mount, Albert Visser, and Timothy Williamson for discussions about the themes of this paper. Õ §Z êZo±í At the origin of logic is the observation that arguments sharing certain forms never have true premisses and a false conclusion. Similarly, all sentences of certain forms are always true. Arguments and sentences of this kind are for- mally valid. From the outset logicians have been concerned with the study and systematization of these arguments, sentences and their forms. -

Propositional Logic (PDF)

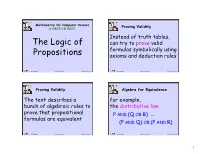

Mathematics for Computer Science Proving Validity 6.042J/18.062J Instead of truth tables, The Logic of can try to prove valid formulas symbolically using Propositions axioms and deduction rules Albert R Meyer February 14, 2014 propositional logic.1 Albert R Meyer February 14, 2014 propositional logic.2 Proving Validity Algebra for Equivalence The text describes a for example, bunch of algebraic rules to the distributive law prove that propositional P AND (Q OR R) ≡ formulas are equivalent (P AND Q) OR (P AND R) Albert R Meyer February 14, 2014 propositional logic.3 Albert R Meyer February 14, 2014 propositional logic.4 1 Algebra for Equivalence Algebra for Equivalence for example, The set of rules for ≡ in DeMorgan’s law the text are complete: ≡ NOT(P AND Q) ≡ if two formulas are , these rules can prove it. NOT(P) OR NOT(Q) Albert R Meyer February 14, 2014 propositional logic.5 Albert R Meyer February 14, 2014 propositional logic.6 A Proof System A Proof System Another approach is to Lukasiewicz’ proof system is a start with some valid particularly elegant example of this idea. formulas (axioms) and deduce more valid formulas using proof rules Albert R Meyer February 14, 2014 propositional logic.7 Albert R Meyer February 14, 2014 propositional logic.8 2 A Proof System Lukasiewicz’ Proof System Lukasiewicz’ proof system is a Axioms: particularly elegant example of 1) (¬P → P) → P this idea. It covers formulas 2) P → (¬P → Q) whose only logical operators are 3) (P → Q) → ((Q → R) → (P → R)) IMPLIES (→) and NOT. The only rule: modus ponens Albert R Meyer February 14, 2014 propositional logic.9 Albert R Meyer February 14, 2014 propositional logic.10 Lukasiewicz’ Proof System Lukasiewicz’ Proof System Prove formulas by starting with Prove formulas by starting with axioms and repeatedly applying axioms and repeatedly applying the inference rule. -

Sets, Propositional Logic, Predicates, and Quantifiers

COMP 182 Algorithmic Thinking Sets, Propositional Logic, Luay Nakhleh Computer Science Predicates, and Quantifiers Rice University !1 Reading Material ❖ Chapter 1, Sections 1, 4, 5 ❖ Chapter 2, Sections 1, 2 !2 ❖ Mathematics is about statements that are either true or false. ❖ Such statements are called propositions. ❖ We use logic to describe them, and proof techniques to prove whether they are true or false. !3 Propositions ❖ 5>7 ❖ The square root of 2 is irrational. ❖ A graph is bipartite if and only if it doesn’t have a cycle of odd length. ❖ For n>1, the sum of the numbers 1,2,3,…,n is n2. !4 Propositions? ❖ E=mc2 ❖ The sun rises from the East every day. ❖ All species on Earth evolved from a common ancestor. ❖ God does not exist. ❖ Everyone eventually dies. !5 ❖ And some of you might already be wondering: “If I wanted to study mathematics, I would have majored in Math. I came here to study computer science.” !6 ❖ Computer Science is mathematics, but we almost exclusively focus on aspects of mathematics that relate to computation (that can be implemented in software and/or hardware). !7 ❖Logic is the language of computer science and, mathematics is the computer scientist’s most essential toolbox. !8 Examples of “CS-relevant” Math ❖ Algorithm A correctly solves problem P. ❖ Algorithm A has a worst-case running time of O(n3). ❖ Problem P has no solution. ❖ Using comparison between two elements as the basic operation, we cannot sort a list of n elements in less than O(n log n) time. ❖ Problem A is NP-Complete.